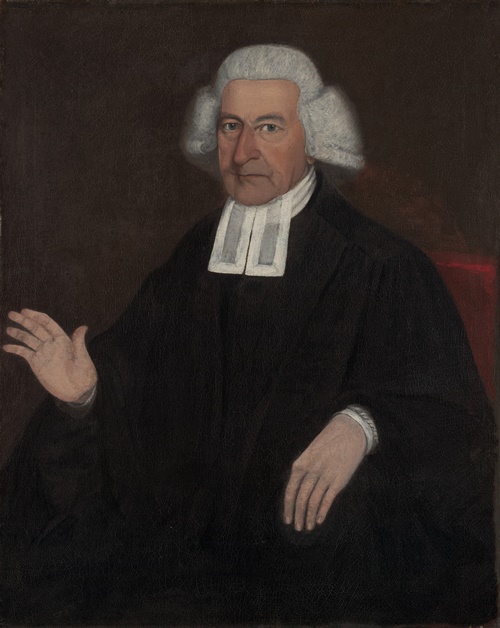

Ezra Stiles, a former president of Yale University, died nearly 230 years ago, but his ghost continues to haunt schools and colleges across the country. In addition to his time leading one of the most well-known educational institutions in the world, Stiles was also a minister, a founder of Brown University, someone who bought enslaved people, and a pen-pal of both Thomas Jefferson and Benjamin Franklin, yet he is largely remembered for something he himself never would have anticipated: introducing grades as a means for evaluating academic work.

Not only was Stiles the president of Yale from 1778-1795, but he was also a faculty member, which required him to examine students on topics ranging from Greek and Latin to rhetoric and mathematics. At this point in Yale’s history, students answered exam questions orally, and they were evaluated publicly in front of their peers other members of the university community.

Stiles kept a meticulous diary, and in a series of entries for the year 1785, he details a rather frenetic week full of student examinations. From April 4-8 of that year, he did everything from writing questions to personally examining students. April 5 is of special significance for our story, though. On this day, Stiles examined 58 seniors. In his diary and other notes, he describes the way he categorized student performance on the examinations. Twenty out of the 58 were classified as Optimi, 16 as Second Optimi, 12 as Inferiores (Boni), and a worrisome 10 as Pejores.

Three of these terms are fairly easy to translate. Optimi means “Best,” while Second Optimi unsurprisingly means “Second Best.” Pejores, the lowest performing group, can most accurately be rendered as “Worse” (not “Worst,” which indicates at least some empathy on the part of Stiles). Inferiores (Boni), on the other hand, is a bit trickier. In the past, some have translated this phrase as “Less Good,” but “the Lower of the Good Group” is probably closer to the original meaning.

Although we may dither a bit about the exact meaning of these terms in English, there are a few points that are incontestable about Stiles’s four categories of achievement. First, they together comprise what is almost certainly the first documented grading system in the history of American education. Before you cheer or jeer him for this, it is important to know that Stiles did not invent this approach. Across the pond, examiners at Cambridge had been evaluating student performance on oral exams using similar kinds of Latin-labeled groupings for much of the eighteenth century. Stiles was simply an enthusiastic importer of this British system, but he can be credited with putting an American stamp on it. As a vocal supporter of independence and the Revolutionary War, which took place during his Yale presidency, I think this might have pleased him.

Second, the clear purpose of this mode of evaluation was to publicly rank and sort students according to their achievement, not to give them feedback on their learning or to suggest how they might improve before the next exam. This kind of class ranking was a mechanism for conveying status and privilege (or withholding them), oftentimes mirroring the social structures of the world beyond the ivy-covered university walls. In the end, Ezra Stiles bears a healthy dose of responsibility for popularizing a system in which public recognition and classification of performance mattered more than individual learning, student development, or the cultivation of curiosity and inquiry — all of which are ostensibly the primary goals of education.

This is grading’s original sin, and — despite centuries of change in American schools and colleges — we have never been able to move past it. From the very beginning, grading was more about sorting, signaling, and certification than it was a system for supporting or enhancing students and their learning. Class valedictorians, Latin honors (like summa cum laude), and GPAs are all legacies of Ezra Stiles in this regard, but even more familiar grading models suffer the same fate.

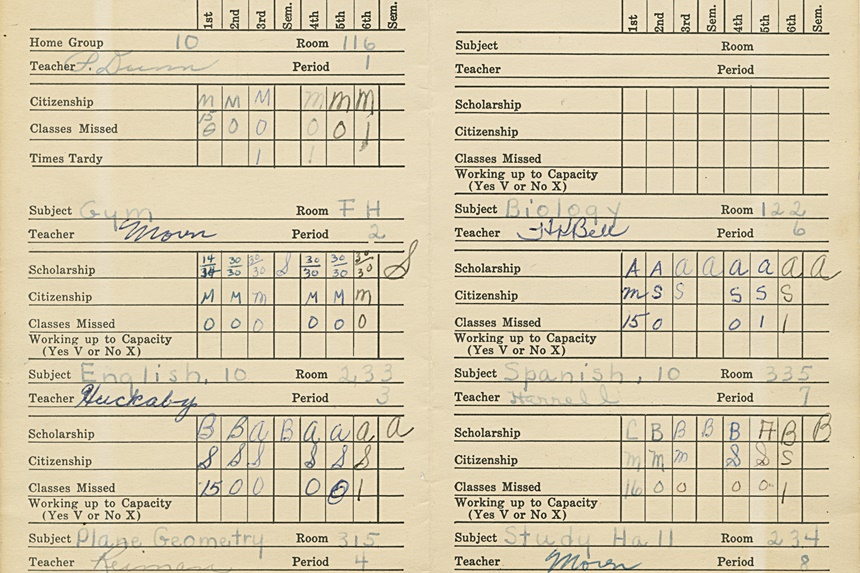

Percentage grades and A-F letter grades, which arrived on the scene in the late 1800s, give slightly more information about a student’s performance in a class, but they still serve the purpose of ranking and sorting, and we also have good evidence to suggest that they are not accurate measurements of learning in the first place. That’s a problem, and students shoulder the burden.

We have now arrived at a pivotal moment for education in America. Armed with an understanding of the problems with traditional grading, teachers and administrators across the country are experimenting with new approaches like standards-based grading, contract grading, collaborative grading, and more. Their goal is to evaluate students in ways that better reflect learning, allow room for mistakes, and account for personal growth.

Those elements of education might not have mattered much to Ezra Stiles in the America of the 1780s, but they are absolutely essential for the future of our nation’s students.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

Standards are a measure we use to see where students are compared to a desirable ‘norm’. Those who want to do away with measures and standards prefer to be evaluated individually. This defeats the purpose of standards as there are may reasons why some do better than others on standardized tests but that is not a reason to do away with them.

How we stand in relation to others is necessary to improve teaching methods and also to see who may be qualified or not, for a specific job or vacation. Perhaps instead of learning how to interpret test results there are many who are frightened of competition – grading of individuals and measuring methods of new inventions etc.. all want the same thing – to see what works and what doesn’t. Those who do not want to see where people or things stand in relation to ‘norms’ may not ever improve …

… The only opportunity in today’s world to showcase ‘excellence’ is in the world of Sports…

Excellence counts in sports – but not in academics? We need to stop worrying about hurt feelings of those who are fearful of standards because they don’t measure up – it ideally ought to spur them to work harder or be satisfied to not always rise to the top of the scale and to work with what talents they have…

It’s not so much that a grading system is bad, it’s how it is used. And that doesn’t even come close to how poorly the USA’s system of education is ‘performing’. Education shouldn’t be restricted to a timetable.

Thank you for reading and engaging with the piece, Bob. I appreciate you sharing your story too. I agree that change is hard—in education especially.

Ezra Stiles was definitely quite a complicated man when looked at in the big picture of things, where I dare say he would probably get more than a few D’s and F’s if given a report card on his own life, and what he put into motion.

Your links here are very much appreciated, Josh. I know I struggled with the A-F grading system myself. My kindergarten teacher (public school) told my Mom she felt I’d do better in the Catholic school for the 1st and 2nd grades in getting the basics down, then return to the public school for the 3rd grade on. So that’s what happened.

I did pretty well in the 1st and 2nd grades. getting C’s to A’s. My favorite part was learning cursive. Loved the Aa, Bb, Cc etc. Sister kept at the top above the green board. The Declaration of Independence signatures (wall copy) fascinated me to no end. I was already handwriting before we were actually taught. So when I’m interested in something, I’m all in to learn. When I’m not, my brain puts up a block of “we don’t like this” and tunes it out.

In the 3rd grade I was back in the public school, and about 6 weeks in was the parent-teacher conference at night. Mom woke me up, upset I’d gotten a ‘D’ in arithmetic, and Mrs. Wagner noticed I was looking outside at the entertaining birds more than paying attention to her. I would have appreciated the teacher taking me aside, and speaking to me first, but she didn’t. She might have had a praise report instead if she had.

10 pm Mom gives me the speech about how she, a college graduate and high school English teacher NEVER got a ‘D’ in any subject, nor my college and law school grad Dad either. How the pediatrician said I was advanced in the tests for infants and toddlers, fully talking at 1 and a 1/2; how could this be?! Try getting back to sleep after that.

I made every effort to improve, but my teacher decided to have me see the school psychiatrist for his determination on it, including an IQ test. The good news was I had a high IQ which made why I wasn’t a good student all the more frustrating.

ANYWAY, in the 4th grade, I had this incredible teacher that “got me”, and I had almost straight A’s and a couple of B’s. So the teacher and hers or his style and method, can make a huge difference, even within the confines of the present system!

After that, I forced myself to learn what my mind was rejecting to pass the damn tests (with cheating only as needed) ) and concentrate on creative writing, English lit, Greek and Roman Antiquity, being on the high school paper, writing record reviews (Carly Simon’s ‘Hotcakes’, Cat Steven’s ‘Buddha and the Chocolate Box’) and got my financial and communications degrees in college.

I actually put those two to good use professionally, but frankly my own natural aptitude should get most of the credit. Society puts too much emphasis in its narrow definitions of what education is or isn’t. Rush them straight into college out of high school by rote so they don’t have time to question anything. Whether their degree will get them anywhere doesn’t matter; just get them on the hook for owing endless thousands of dollars.

Grades are based on passing tests which can often mean a person is simply good at regurgitation of facts, but it doesn’t translate to making intelligent or morally right decisions. The people running this country are probably the most highly educated (on paper) we’ve ever had, but look where we are. That sentence says it all, thank you.

Education and grading need complete overhauls. The one-size-fits-all way has really never worked that well. We have so much over-choice on things we don’t need, yet in this area things are still stuck in 18th century. Unfortunately, keeping things as they are is still profitable for the educational industry, which it is. A profitable industry.