The red-brick Atchison, Topeka, and Santa Fe Railway depot looked out of place near the end of the rail line in Stillwater, Oklahoma. Evan Stair, a student at Oklahoma State University, wondered why such a sturdy, elaborate structure was situated beside a railroad to nowhere.

He inquired of a friend who knew a thing or two about railroad history. His friend replied: “Evan, there was a time in this country when you could walk down the street to your local town depot and travel anywhere in the country.”

The railroad line used to extend farther south. Passengers took a train from Stillwater to larger cities, hopping aboard long-distance passenger trains that would whisk them off to destinations far, far away.

In their heyday, passenger trains glided through small towns and thriving cities in the western United States at all hours of the day and night. Riders were practically countless, and the trains carried high volumes of mail and express shipments. But with the advent of the automobile, Americans took to the highways. Passenger rail’s end was beginning, seemingly.

Today, a handful of long-distance passenger trains still traverse the American West, carrying passengers over rolling prairies, across arid deserts, and through lush forests as they barrel toward the Pacific Ocean and back. Most, however, are gone, and those that remain serve fewer communities.

As some passenger trains were forever sidetracked, so were many of the features that made rail travel romantic. Not everything, however, was relegated to the scrapyards of railroad history.

THE LINE BEGINS

The origins of American passenger rail travel date back to the 1820s, when horses and primitive steam engines pulled crudely constructed wooden cars resembling stagecoaches. Locomotives and passenger cars slowly evolved, but riding the rails was still a rough experience. Passenger George Pullman thought he could make it better.

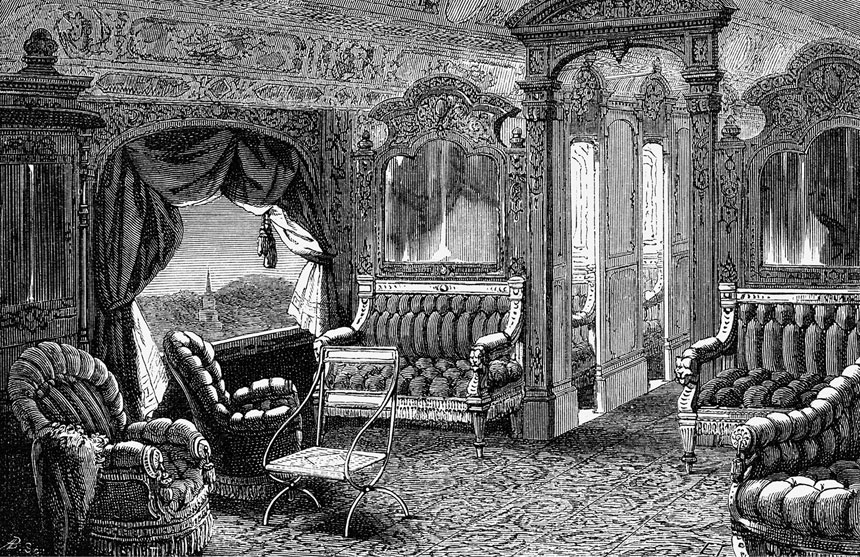

Pullman developed sleeping cars with folding beds, cushioned seats, bathrooms, and plush carpeting, among other amenities. In 1866, The Saturday Evening Post caught on to the public attention toward the cars, reporting in one issue: “Mr. Pullman, the projector of the sleeping-car improvement in railroad traveling, has just placed on some of the western roads new cars, with conveniences, luxuries, and ornamentation quite in advance of anything yet produced.”

Pullman was one of the first to revolutionize passenger rail and make comfort a priority, especially on the long-distance trains that were becoming one of the country’s leading modes of transportation. As the West grew, so did the railroads that hauled freight and passengers there. Still, early passenger rail travel left much to be desired.

“Based on our later standards, the early railroad travel was pretty crude,” says Jim Ehernberger, a railroad historian, author, and retired Union Pacific employee. “The straight coach cars were crammed with smokers and screaming kids that made train trips unpleasant. There were no dining cars, and the railroads provided meal stops. Many of these were inferior operations. The times were limited, and when you had a rush on those places, many had to ‘eat and run,’ and some ‘grabbed and ran’ back to their train in order to avoid getting left.”

Passenger rail boomed until the 1920s; the advent of Henry Ford’s Model T and the modern highway system took its toll, Ehernberger says. By 1927, ridership was down, and railroads wanted it back.

THE STREAMLINER ERA

In the early 1930s, a new kind of train was zipping across the country. It was the art deco architectural design era, and railroads and railcar manufacturers put the contemporary style on rails in a bid to make rail travel exciting once again. These new trains were sleek and futuristic, unlike the bland wooden and metal cars that came before them. The streamliner had been born.

The Union Pacific, one of the largest railroads in the West, was one of the first onto the streamliner scene. The railroad’s M-10000, with a rounded nose and smooth exterior body design, was a brown-and-yellow three-car train unlike anything the nation had seen. Popular Mechanics magazine compared the train to “an elongated, aluminum bullet on wheels.” Its top speed was 110 miles per hour. Inside, a relatively new creature comfort greeted passengers: air conditioning.

The Chicago, Burlington, and Quincy Railroad developed its own set of streamliners: the Zephyrs, all-stainless-steel passenger trains built by the Budd Company. The railroad placed several Zephyr trainsets into service across its network, setting new speed records.

The public was receptive. In its July 28, 1934, edition, the Post reported that crowds along the Burlington line leaped for joy as they watched the new Zephyr race across the Midwest. “The enthusiasm was astonishing, even a little bewildering,” Garet Garrett wrote. “And it was not for anything they could see with their eyes, for that, after all, was very little. A silver streak, a noisy blur, a technical apparition.”

The excitement was justifiable. “You have to think what trains were like before [the streamliners] started,” Ehernberger says. “A lot of people had an attitude that trains were dirty and kind of slow.”

The streamliner played a role in sustaining passenger rail travel for years, including during World War II, when automotive fuel supplies were rationed. Roughly 74 percent of the nation’s intercity passenger travel was done by rail, railroad journalist Fred Frailey reports in his book Twilight of the Great Trains, which chronicles the passenger rail industry’s 20th-century decline.

When the war was over, railroads spent hundreds of millions of dollars to purchase new passenger cars and equipment, Frailey told me in a phone interview. Railroads invested in luxurious dome cars, allowing passengers to gaze up at the night sky and across sweeping plains, and sleeper cars that made multi-day travel relaxing. Railroads were ready to carry passengers and mail for another generation.

By 1949, however, railroads were handling less than half of all intercity travel, Frailey writes, and that share would only decline. Automakers who had been producing war machines were putting cars on the road again, and the public was buying. Airline travel also soared after the war, according to the National Air and Space Museum.

“The capital that they spent, they didn’t get back, and no railroad did,” says Frailey.

Despite the competition, long-distance trains kept charging across the West. The Atchison, Topeka, and Santa Fe Railway — one of the largest railroads in the West — was operating several in 1949. Among them were its famed Super Chief, a luxury train dubbed the “Train of the Stars” because of the number of celebrities who rode it, and the El Capitan extra-fare chair car train.

Similarly, in 1953, the Union Pacific was running its series of streamliners named in honor of cities such as Portland, Denver, and San Francisco. Eleven trains were crossing the state of Wyoming, a major state for the railroad’s operations, Ehernberger says.

Though rail travel was in decline in the 1950s and early 1960s, some customers might not have noticed.

TRAVELIN’ MEN

The year was 1959, and a boy from Corsicana, Texas, was about to take a trip he’d never forget.

For Kelly Martin’s birthday, his aunt took him to Dallas via the Sam Houston Zephyr, one of the Burlington’s streamliners. As the train pulled into the Corsicana station that day, Martin was in awe.

“It was late morning, and it was sunny, and the train came in, and it was all stainless steel and shiny,” Martin remembers. “Oh, it shone in the Texas sunlight. It just almost glittered, it was so beautiful.”

Onboard the train, Martin and his aunt walked to the observation parlor and dining car, where some of the passenger rail service’s most glamorous facets were displayed. Fine Irish linen cloths covered the tables, and real silverware and China plates were neatly arranged on top. The air in the car was cool, and condensation had built up around the outside of the silver ice water pitcher. The coffee carafe was silver, too.

Such dining car experiences were the standard on many 20th-century passenger trains, when waiters donned white suits, and guests wore formal clothing, too.

“When you rode those trains, it was such an uplifting experience. There was so much service, so much attention to the passenger’s comfort and their safety,” says Martin. “It was just a beautiful experience, a beautiful traveling experience.”

The Santa Fe, which Frailey unequivocally refers to as the standard-bearer for passenger rail service, paid special attention to its dining cars. They were operated by the Fred Harvey Company, best known for its restaurants along rail lines. “The Santa Fe had a 95-page set of instructions for how to run a dining car,” Frailey notes. “It was run like a military operation.”

Those standards extended beyond the walls of the dining cars — and beyond the bounds of time and money. Emporia, Kansas, native Scott Thomas still has a cardboard model of a Santa Fe diesel engine, which conductors gave to children onboard their trains. Another Santa Fe keepsake in his railroad memorabilia collection reminds him of a bittersweet day: his ticket for one of the last runs of the Santa Fe Chief on May 14, 1968.

The year prior, the federal government took away the lifeblood that had sustained passenger trains through years of unprofitability: mail contracts. Payments for carrying mail had covered the costs of passenger rail operations for years, and, according to Frailey, the U.S. Postal Service opted to give those contracts to the airline industry. Money-losing passenger trains were shut down in relatively short order, and the Chief was not spared.

Even in the Chief’s waning years, everything about it — from the cleanliness of the coach cars to the sweet taste of the French toast in the dining car — remained unchanged, Thomas says.

“I remember being really sad. I probably had tears in my eyes. I grew up as a Santa Fe kid — Santa Fe all the way,” Thomas says. “I’m grateful that I was able to experience Santa Fe as the Santa Fe. They kept it spit-polished until the very end. Some other railroads were letting their passenger service decline and just become real nasty, and the Santa Fe carried on.”

THE AMTRAK ONSET

Some passenger trains didn’t look much different from April 30 to May 1, 1971. But the latter day marked a new chapter for American passenger rail travel. The Amtrak era had begun.

The National Rail Passenger Corporation, nicknamed “Amtrak,” was formed to take the money-losing passenger trains off railroads’ books, keep some trains going, and do the job with the help of federal subsidies. Although passenger ridership was down, government leaders thought some passenger routes were still important parts of the national transportation puzzle, Frailey reports. On its first day, Amtrak operated about half the trains that had been roaming the nation’s rails from coast to coast.

The financial suffering of Western railroads and long-distance trains weren’t the only reasons — or even the main reasons — behind Amtrak’s formation. The failed merger of the New York Central and Pennsylvania railroads threatened to derail passenger transit in the heavily populated northeast, where commuter trains long have been essential to travel.

“Amtrak, it got off to a very, very hopeful start, but it got off to a really rocky start,” says Bob LaPrelle, president of the Museum of the American Railroad in Frisco, Texas. “I think Amtrak was created out of the mess from the Penn Central bankruptcy, and they had to do something with the northeast. They had to maintain service there, but they couldn’t carry such an endeavor without national support. I think that Amtrak was created as a national system to get the political support to do anything at all.”

That support was necessary. President Richard Nixon was among those who didn’t believe the national system would make it, as Wired magazine writer Nick Stockton reported in 2018. Some say Amtrak was designed to fail. But a few historic events — such as the Arab oil embargo, which temporarily boosted ridership — kept it going.

“Here we are, 50-some-odd years later,” LaPrelle says.

Although Amtrak is responsible for keeping passenger rail alive, much about the service has changed. The most noticeable difference: The frequency of trains is greatly reduced. During passenger rail’s golden era, multiple trains would have stopped in towns like Newton, Kansas, allowing passengers to board and disembark throughout the day. Now, the Amtrak Southwest Chief is the only one. The eastbound and westbound Chiefs both arrive in Newton around 2 or 3 a.m., if they’re on time.

As for standards of service in the dining cars, Frailey compares Amtrak to “the tides of the ocean.”

“It’s so unlike what it used to be,” Frailey says. “They either have white table cloths or they have wax paper. It depends on the mood in Washington. They either have nice forks and spoons — real stuff — or they have plastic. They either have real plates or paper.”

Thomas has ridden the Southwest Chief a few times, and although he sees the differences in service, he’s optimistic about Amtrak operations. Amtrak has its critics, but his experiences have been generally pleasant, he says. Still, Amtrak “has a long way to go to equal Santa Fe.”

LaPrelle, who rode the Texas Eagle as a boy, says he believes Amtrak is a rolling miracle. It’s survived years of political bickering over funding, the ebbs and flows of the traveling public’s interest, and more.

“Amtrak is still a necessary conveyance,” he says. “I don’t think it’s frivolous. I don’t think it’s a waste of money. I think it plays a role, a very important role, in maintaining a balanced transportation system, particularly with smaller communities.”

AMTRAK COMEBACK?

Nearly 30 years ago, Oklahoma native Evan Stair fell in love with passenger rail travel when he and his wife took an Amtrak trip on their honeymoon. Amtrak service had ended in his home state years earlier, so when Amtrak’s Heartland Flyer took to the rails there in 1999, he saw an opportunity.

The Flyer had more than 71,000 riders in its first year on its run from Oklahoma City to Fort Worth, Texas. If it could just run north to Newton, Kansas — allowing for a connection with the long-distance Southwest Chief — ridership and economic development could increase, Stair thought. Ever since, he’s been a passenger rail advocate, urging elected officials and Amtrak leaders to support the expansion of passenger rail operations.

There’s more hope for that connection today than there has been for some time. The 2021 Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act allocated $66 billion in funding for railroad improvements, and it required the Federal Railroad Administration to study the viability of restoring some long-defunct passenger rail routes. In late 2023, the agency selected 69 passenger rail service proposals to receive grant funding for future study as part of its Corridor Identification and Development Program, the first step toward potential expansion. The projects could create new Amtrak routes, expand or upgrade service along existing routes, or create high-speed rail service, though it will likely take years to get rolling.

“It is an opportunity to, at a minimum, market and expose the people of this country to passenger rail, and it’s a positive story,” Stair says.

Marc Magliari, Amtrak’s senior public relations manager, believes restoring those routes will require significant investments.

“Having interest in these last 50 years is one thing, but having funding to make those interests real, or at least study what’s practical, has never been available. So, it’s a new time,” he says. “There already is a revival. We can’t add trains fast enough to some of these markets today.”

In part, that is perhaps because some travelers know what train travel has to offer: precisely what other modes of travel don’t.

Magliari has seen strangers strike up conversations during a meal, play card games, and even have guitar jam sessions while traveling on Amtrak trains. There’s a lot more space on a train than a bus or plane — and there are no middle seats.

“It just feels different, and it’s part of the unique nature of it, I believe, that people are basically a bit more social,” Magliari says. “You’re certainly not cooped up in a car, and you have the choice to be staying in your sleeping car [or] private room. You have the choice to be sitting in your coach seat or to get up and walk around and encounter people and meet people from other places in the U.S. or other places internationally who are with you on the train, sharing the experience.”

Train travel is always slower than a flight and gives the traveler less control than a car does. Amtrak’s own data shows that many of its long-distance trains in 2022 were late more than they were on time, a quandary the company blames on host railroads. If speed is a customer’s primary reason for traveling, Amtrak may not be the answer. A train trip, by its nature, gives the passenger a slower way to travel and takes the passenger back to an era when transportation was enjoyed, not endured.

“On a passenger train, you’re eye-level with the country-side. You’re actually looking out the window. I’m staring into the piñon pines or across the canyons or the deserts or across the farmlands of Kansas or the Midwest,” Thomas says. “Part of the experience was not only the destination, but the journey. Going somewhere was a part of significance as well as just getting there.”

Regularly scheduled passenger trains haven’t passed by the Stillwater depot for decades. There’s talk that some of the remaining rusty rails in town may be ripped up. But across the nation, hope for passenger rail travel’s future glows like the windows of a passenger car sailing across the Western prairies at night. Stair and other passenger rail advocates still dream of a day when passenger trains connect more of the country — like they used to.

“I believe in the economic promise of a wider passenger rail network,” Stair says. “I believe it’s important for the people.”

Jordan Green is a reporter at the Longview (Texas) News-Journal. A 2023 graduate of Northwestern Oklahoma State University, he has been in the newspaper business since 2017 and served as editor-in-chief of the Northwestern News. He was an intern at The Saturday Evening Post in the summer of 2022.

This article is featured in the May/June 2024 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

Thank you, Jordan! I love trains though I’ve never had the chance to travel by rail in the US. I read a report somewhere that explains one reason that trains have fallen out of favor in the US is that the stations are no longer centrally located within cities so that when you arrive at your destination, you cannot simply walk to where you want to be. You need to take a taxi or Uber to your next destination. Airports often have shuttles to hotels and other venues, but I’ve never seen a train station with a shuttle.

Amtrak runs an auto train from Orlando, FL to Lorton VA and vice versa, once each day. You can choose, as a passenger – coach, roomette, or a handicap accessible room. The trip is 16 hours and meals and snack bar are available. I’ve taken it many times until recently when the prices for air travel outdid train fare. But with air fare you did not have your vehicle as you do with the train.

In the summer of 1955, our family rode the Chicago and Northwestern and Union Pacific “City of Portland” from Cedar Rapids, IA to Portland, OR. I was 9 years old at the time. I was overwhelmed to say the least. I recall everyone was dressed up, the employees went beyond the call of duty to serve you, the dining car had real china, tablecloths, and flowers and the waiters waited on you hand on foot. Then there was the dome car, which provided unbelievable vistas of the West. The experience was a class act. I am so thankful that I was able experience the tail end of the golden age of train travel.

When I migrated to Australia, I fired and drove steam trains. It was an adventure I shall never forget.

Thanks for this aricle re: the glories of train travel. I still take a room from Florida to Philly or NYC and have the best time en route. There’s no more of an enjoyable, hassle-free way to cover the miles. Now, if we could only have high speed trains from NY to FLA; it would be a bit of heaven. Imagine a trip between the two lasting eight hours, including major stops, and seeing parts of the country you would never witness by car or plane. Better for people and better for the environment. We don’t need all this benzopyrene at our airports and travel hassles just to reach the airports instead of boarding in urban centers and arriving in media res, too.

I love trains, hope they continue to expand, We took a train from Boston to Seattle Wa. in the 90’s near Chicago

they have the Lake Shore Line, we renamed it The Late for sure Line. It was always late, we had to run to catch

the Empire Builder to Seattle.

I suppose I got my love of trains from my father, who went to work for the Denver & Rio Grande somewhere around 1920, when he was still a teenager. He moved on years later, to California, and raised a family of seven kids. When my mother died in 1967, the first thing Dad did was board a train to Colorado. just to visit and take the train trip. He always loved the trains.

A Big “THANK YOU” to Mr. Jordan Green for his fascinating, detailed story regarding the progression of train travel in America. I don’t know of any, or many, young boys who have grown up without having any interest in these magnificent machines and the mystery that initially surrounds them in the eyes of a young boy watching them pass through his neighborhood.

As a young boy, I used to hop the slower moving freight trains, despite the dangers I had been warned came with such an act, and it always gave me a sense of exhilarating freedom. This article brought back so many of my own childhood memories, such as the one time I actually rode in a passenger train from Columbia, S.C to Summersville, W.VA. by myself to visit my Grandparents.

Great article, Mr. Green. Thank You Again!

I’m old enough to have experienced Southern Pacific passenger trains in the 1950s, and everything the author says about the glamor of rail experience back then is true.

A child of the 1940s, I grew up on the South Shore Railroad line between South Bend, Indiana, and Chicago. And, after moving to Fort Wayne, I became familar with the Pennsylvania Railroad Baker Street Station in that city. My stepfather was a fireman on the PRR. Rides on the PRR to visit my grandmother (Nana) in Chicago were the most exciting. And continue to hold cherished memories.

A railroad pass was a golden ticket to not-so-far-off destinations for my family, which seldom owned a car; the station a cavern of comforting and familiar sounds and sights: Ticket windows where clerks mysteriously appeared to serve travelers. Luggage-laden carts pulled up and down ramps.

Closer to the Windy City, Gary, Hammond, East Chicago and Whiting signaled their presence, industrial smokestacks belching out smoke and transforming the sky into an aerial display: a palette of blues, yellows, gray, black and white. In retrospect, not a healthy environment for area denizens, but a Technicolor marvel to young travelers’ eyes.

And always, on the return ride, we’d holler out when we spied the gigantic General Electric sign, a welcoming beacon in the night sky, signaling we were nearly home. (The former GE plant now houses Electric Works, which draws visitors from far beyond FW borders.)

Nana and I climbed aboard the PRR when I was eight years old, enroute to New York City and Washington, D.C. A few years later, the entire family embarked from Baker Street for Mobile, Alabama, where Uncle Carl was stationed with the Air Force.

The PRR, indeed, was the railroad of my brother’s and my little worlds, along with thousands of other kids of that era who recall no words more exciting than the conductor’s welcoming cry: “All aboooooard!!”

CJ Woodring

I love trains, so, of course, really enjoyed this article. The picture of people eating on the train caught my attention. I was very interesteed in the picture because the woman who is facing the camera looks like she could be my twin sister! I don’t suppose you have any information about who they were or where they were from, do you?

I love trains!

Having grown up in Switzerland, trains always were and still are an essential part of the daily transportation experience!

The Swiss now have series of “special trains” for exclusive travel experiences! They are great!