When America’s last Coast Guard lighthouse keeper hung up her old-fashioned bonnet last year, the movement marked the end of an era. Sally Snowman, who was 72 when she retired in December, had cared for the 308-year-old Boston Light, which is perched on Boston Harbor’s Little Brewster Island, since 2003. Sometimes she donned homemade, 18th-century garb for her work, which included offering public tours of the rocky, wind-strafed island — more utilitarian moods found her zipped into a Coast Guard–issued jumpsuit instead. For 15 years of her tenure, she lived year-round in the island’s 1884 Light Station Keeper’s Quarters, at times riding out whiteout blizzards and fierce storms that raked the two-acre scrap of land with 20-foot waves.

“I say I have salt water in my veins, and not blood,” says Snowman. “I’ve had a connection to lighthouses since I was yea high to a caterpillar, growing up in Boston Harbor.” Though the Boston Light was fully automated in 1998, congressional law stipulated that the landmark, which was the very first light station established in colonial America, remain manned. The verb doesn’t quite fit Snowman, who was both the first and the last female keeper of Boston Light. She will not be replaced. “Will I miss it?” Snowman asks. “Yes, I will.”

If Snowman’s retirement is the poignant coda to lighthouse keeping by the U.S. Coast Guard, it comes amid a transformation of the country’s coastlines that’s been unfolding for decades. Though lighthouses remain essential navigational aids for boaters, they no longer require the live-in keepers who tended lamps and rowed to aid boaters caught in deadly squalls. And so, from Michigan beaches to Maine’s scatter-shot bays, government-owned lighthouses are going to a new generation of keepers. Since 2002, in a program run by the General Services Administration in collaboration with the U.S. Coast Guard and the National Park Service, more than 150 lighthouses have been sold off or given away to nonprofits, friends associations, and private citizens.

Government sales are not unusual in themselves — you can buy all sorts of things from the feds. A recent scroll through the GSA’s online auction site presented opportunities to bid on a 1985 fixed-wing Cessna airplane, a five-piece cookware set of unknown vintage, or a diesel generator spray-painted with sylvan camouflage. Lighthouses are different. Unlike used pots, historic light stations don’t simply go to the highest bidder. That’s because the National Historic Lighthouse Preservation Act of 2000, an amendment of the 1966 National Historic Preservation Act, directed the GSA to seek the best possible stewards for federally owned historic light stations up for disposal, holding a competitive application process before sending the lighthouse to a public sale.

The result is a changing of the guard at American lighthouses and an unusually collaborative inter-agency program that has drawn passionate amateurs and organizations dedicated to preservation of maritime heritage. “One of the goals of the National Historic Lighthouse Preservation Act was to promote the preservation and cultural and educational use of these lights, to kind of pass on that history,” says John Kelly, director of the New England region for the GSA. “We have a whole new generation of lighthouse folks coming up.”

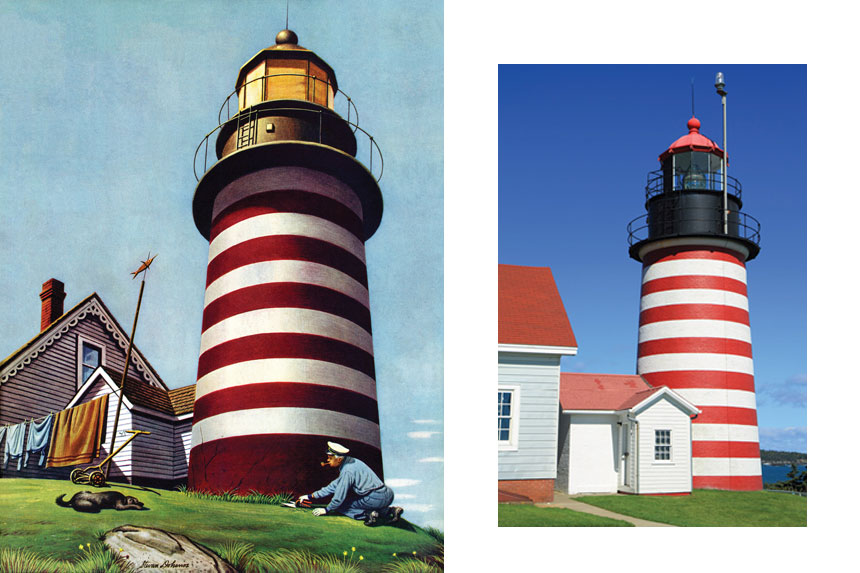

If plenty of would-be lighthouse keepers are eager to step into the breach left by the Coast Guard, perhaps it’s because the signal lights still tug at something enduring in the America spirit. Lighthouses remain some of the country’s most beloved landmarks. Avid road trippers zip along coastlines toting sightseeing “passports” from the United States Lighthouse Society, filling up the books with stamps from hundreds of participating lighthouses. Lighthouses grace children’s books and jigsaw puzzles, and have been a favorite subject for American artists, including the painter Edward Hopper, whose depiction of the lighthouse at Two Lights in Cape Elizabeth, Maine, has all the bittersweet glow of childhood’s endless summer afternoons. Post cover artists Mead Schaeffer and Stevan Dohanos painted lighthouses, too, and from the candy-striped West Quoddy Light to the Cape Cod dunes, their saturated midcentury images are rich with nostalgia.

“People have long appreciated lighthouses. In popular culture, they’re often settings for romantic sorts of novels, you know, sea captains on the stormy coasts,” says Susan Tamulevich, director of the New London Maritime Society. They have a sparkle absent from other maritime infrastructure. “It’s not like people are writing about buoys or shipping channels — those have not inspired literature and the arts,” Tamulevich says.

The nonprofit organization that she heads, which is based in New London, Connecticut, is dedicated to preserving the heritage of a region formed by the sea. It has also become a habitué of the lighthouse scene. NLMS adopted the city’s octagonal 1801 Harbor Lighthouse in 2009 through the GSA program; then, in 2013, it took on the 1878 Race Rock Light, a stout little island signal that warns ships away from a dangerous reef on Long Island Sound. Two years later came the brick-red Second Empire–style New London Ledge Light, and an application for a fourth lighthouse is pending. The NLMS offers boat tours of its two island lights, and visits to the mainland Harbor Lighthouse by appointment. That means Tamulevich has had plenty of time to reflect on the American enthusiasm for lighthouses. “For centuries people traveled, by and large, on the water,” she says. “Anything that helped with safety had great significance to people.”

Picture it: the sea voyage, the foggy night, a coastline where a snug harbor’s safe haven lies a compass-twitch away from the rocky shoals. Every lighthouse has a distinctive pattern of flashes — a code any local seafarer would know by heart — so spotting one offered an instant orientation, and, with any luck, a signal that home was near. Even as we’ve turned to journeys by land and air, Tamulevich thinks, lighthouses’ consoling blink has lingered in our country’s collective memory. “I’ll quote what a Frenchman visiting our lighthouse once said: that they are, to America, what castles are to Europe,” she says.

Come July, nostalgia for lighthouses hits a high. For most of us, though, it’s a seasonal fling — we snap some photos on vacation, buy a few postcards, then tuck our lighthouse passports away, along with the beach chairs and pails, until summer returns. That is not how it works for Nick Korstad, a serial lighthouse owner and current president of the American Lighthouse Foundation.

“I don’t know if it was a past life, or what brought it upon me — by fifth or sixth grade I just really liked lighthouses, and it just became an obsession,” Korstad says. He bought his first lighthouse, Chesapeake Bay’s Wolf Trap Light, at a GSA auction in 2005. Korstad then spent three years, from 2010 to 2013, restoring the 1881 Borden Flats Lighthouse, a pert, red-and-white-striped “sparkplug” light that sits where Massachusetts’ Taunton River meets an arm of Narragansett Bay. He turned the historic landmark into a bed and breakfast, where the “overnight keepers program” sells out months in advance.

Korstad relishes the challenges of historic lighthouse restoration. He strives for period-appropriate wooden windows, sources special mortar to match vintage bricks, and reglazes glass in lantern rooms each year. “Construction of these properties was not with modern tools,” he says. “You are trying to keep the house historically accurate — you don’t want to take away stuff and replace it with something new unless it’s vital.” The stakes go beyond his personal dedication to caretaking. The enthusiasm that lighthouses inspire often extends to the surrounding community and visitors, he says. Landmarks come with an audience; if you screw things up, they’ll notice.

He also warns the lighthouse-curious that historic restorations of the structures often run three or four times over initial project estimates. Buying them is an expensive habit. But what is passion for, if not shouting down that sort of good sense? Since buying the Borden Flats Lighthouse, he’s light-hopped around the United States, making purchases on Lake Huron, the Connecticut coast, and Michigan’s Upper Peninsula; his next project is the Browns Head Lighthouse on the mid-coast Maine island of Vinalhaven.

Korstad isn’t alone in his lifelong romance with lighthouses, but even more casual buyers are susceptible to their charms. “I wasn’t one of those lighthouse fanatics,” says Sheila Consaul, who bought the 1925 Fairport Harbor West Lighthouse at the mouth of Ohio’s Fairpoint River in 2011, following a GSA auction. “I was just looking for a summer home, and I happened to hear that the government was auctioning off lighthouses.” Her mind was more on relaxation than renovation, she says: “What I was picturing was something on the lake, beautiful views, sailboats, birds flying, being at the beach — and it turned out that way! I’m sitting in the lighthouse right now, and it’s an absolutely spectacular day.”

Still, Consaul’s well-earned calm comes after years of work. “Nobody lived in this building from the 1940s until I moved in,” Consaul explains. Plaster hung from the walls; every door was missing, as was anything light enough to pry up and carry off. The lighthouse is on the beach, a half-mile from the nearest road. Everything she needs, from a gallon of milk to a new mattress, must be lugged over sand dunes or come by boat. The big stuff arrives via barge equipped with a crane.

Though Consaul may not have started as a lighthouse fanatic, she now savors her piece of American maritime heritage, and sometimes chats with other lighthouse keepers across the U.S. “It’s just the beauty of it, the beauty and the history,” she says. To reach its perch on the edge of the Fairport River, her lighthouse traveled across Lake Erie by ship from a factory in Buffalo, New York. The original cast-iron staircase is intact; so are the wooden windows and tiled floors. Each year on June 9, to mark the date when the lighthouse first shone, Consaul holds an open house and invites the community into her summer home. Sometimes, GSA handovers result in more public access, not less. “People who lived here, who stared at the lighthouse their entire lives, never got to see the inside,” she says. “Being part of that community is really important for me.”

Consaul is not alone among owners with ideals of accessibility; and her light, maintained during occasional visits from the Coast Guard, still guides boaters safely by, as do hundreds of lighthouses across the United States.

So what did we lose when Sally Snowman left her post at Boston Light? Our most nostalgic lighthouse reveries conjure a time that’s already long gone, when keepers trimmed midnight wicks and pointed their spyglasses out to sea; in her way, Snowman sat vigil for that era. And yet the new generation of lighthouse-keepers still speaks, as Snowman does, of stewardship, of caretaking an American legacy for those yet to come. Boston Light has been sold to an as-yet-undisclosed buyer. They plan to open Little Brewster Island to public tours once more, Snowman told me.

For its former keeper, the lighthouse is a living entity. She prays for it — several times a day — and welcomes the thought of visitors returning to Little Brewster Island, the two-acre kingdom she once roamed in ankle-length skirts. For now, on shore, she’s giving talks and doing some writing. She teaches Kundalini yoga four days a week. She practices Reiki, and plays a handmade drum made from buffalo skin. Perhaps decades spent gazing out to sea taught her its knack for embracing change. “The ocean is constantly changing,” she says. “As the sun goes from east to west, as clouds come over, as storms come through — it’s never, ever the same twice.”

Jen Rose Smith has written for the Washington Post, CNN Travel, Condé Nast Traveler, AFAR, Rolling Stone, USA Today, and Outside Online and is the author of six travel guidebooks to Vermont and New England. For more, visit jenrosesmith.com.

This article is featured in the September/October 2024 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

A really excellent, in-depth look at an important American institution that needs the right people looking out for its welfare and best interests. It looks like this is happening, and the future looks good for them, as it should. The comparison that lighthouses are to America what castles are to Europe is an accurate one, and one we can be proud of!