“Is my baby all right?” It’s the first question the mother of a newborn asks her doctor. The answer depends upon how the baby scores on the Apgar test at one and five minutes after birth.

The ten-point test, which is performed by a doctor, nurse, or midwife, rapidly assesses the infant’s heartbeat, respiration, muscle tone, reflexes, and color. Healthy babies score between 7 and 10. Scores lower than 7 indicate the child needs medical treatment. Named after obstetrical anesthesiologist Virginia Apgar, the test has become the standard measure of newborn health since the 1950s and has reduced infant mortality worldwide. Today the term “Apgar” has become a mnemonic for a newborn’s Appearance, Pulse, Grimace (reflexes), Activity, and Respiration.

Ironically, Apgar’s expertise resulted from a discouraging comment by Dr. Allen Whipple, chairman of surgery at Columbia’s College of Physicians and Surgeons (now Columbia University Irving Medical Center) that women rarely succeeded as surgeons. Instead, he advised 26-year-old surgical resident Apgar, one of the few women doctors at Columbia, to pursue the new medical specialty of anesthesia because she had the “energy and ability” to make a difference.

After Apgar completed anesthesia training at the University of Wisconsin and Bellevue Hospital, she returned to Columbia, where in 1938 she became director of the new Division of Anesthesia and the first woman to head a division. Over the next 11 years she taught at the medical school, where she attended births, conducted research, and published scientific papers. In 1949, Columbia upgraded the division to the new Department of Anesthesia. That same year Apgar became the first woman to become a full professor there, but to her disappointment, a male colleague was appointed chair of the department.

Refusing to be discouraged, Apgar focused upon researching maternal anesthesia on newborns and lowering the mortality rate. “Birth is the most hazardous time of life,” she later wrote in her book Is My Baby Alright? co-authored with Joan Beck. “3.5 percent of babies do not survive the period spanning the last four weeks of pregnancy; the process of birth itself and the four weeks immediately following.” Observing the infant brain was “particularly endangered by the process of birth.” Apgar collected data on 17,000 births and developed a scoring method to assess a newborn’s vital signs. One day, while talking to a medical student over lunch, she jotted down her method on the back of a card, and by 1953 her test was formally adopted by the medical community. “Apgar has “done more to improve the heal of mothers, babies and unborn infants than anyone else in the 20th century” former Surgeon General Julius Richmond later said.

Born on June 7, 1909, to Helen and Charles Emory Apgar, the future doctor had two older brothers in a home so lively that they “never sat down.” Lively and popular, Apgar was a gifted student who played the violin and dreamed of becoming a doctor. A few years later while studying at Mount Holyoke College, she wrote her parents, “I’m very well and happy, but I haven’t one minute to breathe.” That was an understatement. As a college student, Apgar participated in seven sports teams, wrote for the school newspaper, played in the orchestra, and held a part-time job.

The depth of her knowledge in zoology, physiology, and chemistry was so impressive that when Professor Christianna Smith was recommending Apgar for a scholarship, she wrote, “It is seldom that one finds a student so thoroughly immersed in her subject and with such a wide knowledge of it.” Four years later, she received her M.D. degree from Columbia University’s College of Physicians and Surgeons, entered its surgical intern and residency program, and then switched her focus to anesthesiology.

Despite mid-century improvements in medicine, Apgar noticed that while the infant mortality rate declined between the 1930s and the 1950s, the number of deaths within the first 24 hours of life remained static. Frustrated by those figures, she left the medical college and acquired a master ‘s degree in public health from Johns Hopkins School of Hygiene and Public Health. She then joined the National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis — now the March of Dimes — where she became vice president for medical affairs and director of the research program on birth defects. After studying the relation between gestational age at birth and infant deaths, she turned her attention to the problem of prematurity. Apgar was an engaging speaker and consequently traveled thousands of miles each year to promote public awareness of birth defects and the need for more research. She routinely carried resuscitation equipment with her when traveling. When questioned, she explained, “Nobody, but nobody is going to stop breathing on me.”

Apgar always insisted that “women are liberated from the time they leave the womb,” and while objecting to sexual inequality especially over salaries, claimed her gender hadn’t imposed significant limitations on her career. Instead, she simply carved out new areas to research and explore. When asked why she didn’t marry she drolly replied, “It’s just that I haven’t found a man who can cook.” A music lover from childhood she continued to play the violin and cello and often participated in amateur chamber quartets. After a friend introduced her to the craft of building instruments, the two of them fashioned a violin, a viola, and a cello. Apgar also enjoyed gardening, golf, and stamp collecting and, in her fifties, took up flying lessons. She was the recipient of numerous awards, including posthumous ones from the United States Postal Service in a 20 cent Great Americans series stamp in 1974. A year later Apgar was inducted into the National Women’s Hall of Fame.

On August 7, 1974, at age 65, Apgar died of cirrhosis of the liver, but her name lives on through the millions of babies she saved and as one of the brilliant researchers in medical history.

Today, when mortality rates for babies during their first year of life remain significantly higher than those in other developed countries, Apgar’s advice promoted in a March of Dimes slogan of the 1960s, “Be good to your baby before it is born,” resonates even more than it did decades ago.

Nancy Rubin Stuart is the author of many books on women and social history. www.nancyrubinstuart.com.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

It absolutely is a great article on an extraordinary woman. Making a huge difference in the human condition doesn’t get any more basic than making sure newborns are okay right from birth, with her crucial vital sign checks.

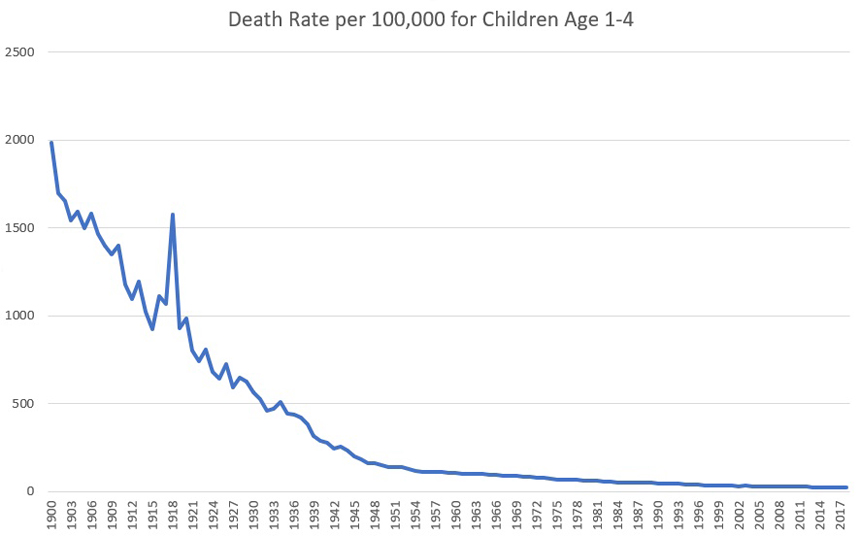

The graph you included above shows the steady decline in death rates of children 1-4 with basically a rapid downward trend starting in 1900, but with a sharp increase during World War I which also coincided with the 1918 influenza pandemic, where the downward trend to the present resumed again after that.

What a great article and credit to her profession as Dr Apgar was! She contributed much to modern medicine today.