As I pushed off from Pittsburgh’s Point State Park — where three rivers converge beneath a skyline of steel and stone — a wave of anticipation washed over me. The sky was gray, promising rain, but all I could feel was the pull to begin my first multi-day bikepacking adventure.

The night before, Amtrak deposited me into the quiet hum of the city just before midnight. I wheeled my bike through the deserted streets to a high-rise hotel a few blocks from this spot: mile zero of the Great Allegheny Passage. I hardly slept. My mind buzzed — with excitement and curiosity about the trail ahead of me.

Known as the GAP, this 150-mile rail-trail winds from Pittsburgh to Cumberland, Maryland, threading through river valleys, old coal towns, and railroad relics. With panniers loaded — tent, sleeping bag, snacks — I pedaled alongside the Youghiogheny River. By the time I reached West Newton, 35 miles in, I’d found my flow.

Bryan Perry, executive director of the Great Allegheny Passage Conservancy, believes the trail resonates with everyone. “Trails are bipartisan. They are enjoyed similarly by folks of all different backgrounds,” he says. “I think that’s why folks from all over the world come to ride the GAP. People love to share the details of their ride, of who they met.”

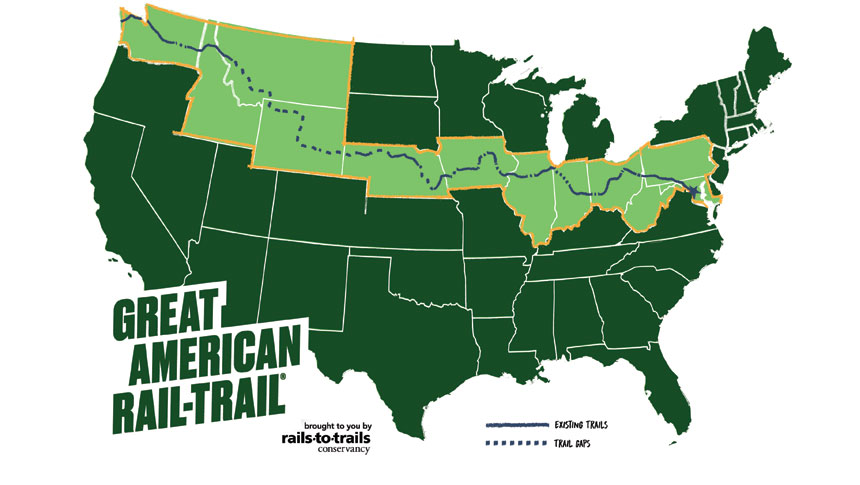

The next day brought steady rain. I was soaked but smiling (well, mostly smiling). I also wasn’t alone, even in the rain. The GAP welcomes more than 900,000 visitors on average each year. It’s one segment of the 3,700-mile Great American Rail-Trail, a route that will one day connect Washington, D.C., to Seattle, Washington. I was heading east this time, but one day, I hope to ride west, into the sunset, all the way to Puget Sound.

This dream of a coast-to-coast rail-trail officially came to life in 2019, after more than half of the 3,700-mile route had been stitched together. But its origin story began decades earlier, in a room with a wall-sized map, red and blue pushpins, and a vision. That’s where two people from the Rails-to-Trails Conservancy (RTC) — Peter Harnik, co-founder, and Marianne Fowler, advocacy strategist — first realized that a cross-country trail wasn’t just a fantasy. It was actually possible.

David Burwell, an RTC co-founder, had imagined a nationwide trail system as far back as the 1980s. This bold idea helped propel the nonprofit’s mission to turn abandoned rail corridors into multi-use trails, reclaiming long forgotten routes and reconnecting once-thriving communities.

Once finished, the trail is expected to put 50 million Americans within 50 miles of the route. For the towns along the way, it offers a chance to attract visitors, new businesses, and fresh energy. Today, 55 percent of the trail is complete — more than 2,000 miles for walkers, cyclists, and adventurers.

“This is really about bringing communities together across their own geographic differences,” says Brandi Horton, RTC’s vice president, communications. “Our tagline for this project is ‘United by Trail.’ Everyone’s there to wave and meet each other, and there’s a special kind of connection.”

On the Great American Rail-Trail, the landscape may be what draws you in — but it’s the people who stay with you. My first night on the GAP, I met a trio of burly firefighters from Cleveland. We camped at the same site, and by chance landed at the same campground the next evening. We grabbed dinner together, enjoying an easy camaraderie that comes from shared miles.

The next morning, I stopped at Mitch’s Fuel & Food for fluffy pancakes, eggs, and bacon. Through the picture window, a dozen cyclists from a West Virginia-based cycling club spotted me — panniers packed — and waved me over to their table. They were excited to chat with a through-rider tackling the full GAP in one go, eager to swap stories about trails, bikes, and time in the saddle.

Perry says he counts trail users several times a year to estimate visitation — but for him, it’s also about connection. “Talking to travelers, hearing their stories, where they’re from, what they enjoy, it’s so delightful,” says Perry. “It keeps us connected to the folks who are out there enjoying common elements: exercise, sunshine, nature.”

Trail towns can offer campgrounds, motels, even historic inns. At Yoder’s Guest House in Meyersdale, Pennsylvania, I lingered over breakfast with a foursome of 60-somethings from Seattle, all smiles and frittata-fueled for the day’s ride. Innkeepers love talking to guests, notes Perry. “Everything they unpack from the day is positive — where they went, what they’ve seen.”

When something goes wrong, strangers step up. Horton recalls struggling to fix a flat on the C&O Canal Towpath, a YouTube tutorial video playing on her phone. A passing cyclist noticed and stopped. “ He not only helped me fix the tire,” she says, “but he did it slowly and showed me how.”

“When you’re on the trail, you’ve got a problem, you’ve got an issue, people are like, ‘How can I help?’” she adds. “Those are the moments when humanity really shines.”

In a world that moves fast — scrolling headlines, packed calendars — the Great American Rail-Trail offers something radical: the invitation to slow down.

“Since the trail goes through so many small towns, I think that’s a really big thing,” says Kevin Belle, RTC project manager. “We want this to be an accessible trail for the greatest amount of people. Having this new life coming through is exciting.”

As you pedal crushed limestone and shaded paths, you sense what’s at stake. Every mile is a piece of history, a link to small towns eager for new energy and fresh starts. It’s a reminder of the historic and natural landscapes we aim to preserve.

“There’s not been something as big introduced since the Appalachian Trail. This is something that’s going to cover a broad section across the American experience,” says Horton. “Our goal is that people will embrace it as theirs locally. They’ll embrace it as part of their everyday life, but it will really bring Americans together.”

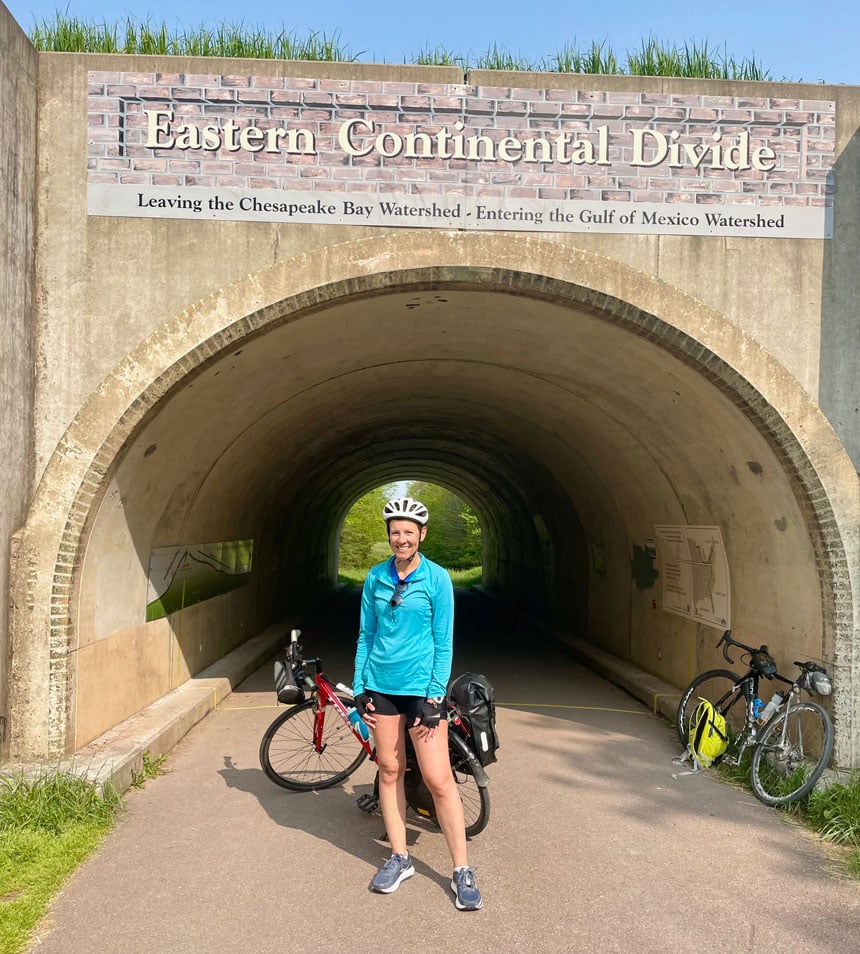

As I closed in on Cumberland, legs weary but heart full, I took time to reflect on the journey. Sitting on a bench, I gazed northward at the sprawling farmland and distant windmills. I wasn’t quite ready for the ride to end. In those last few miles, I paused to snap photos of the final trail markers, to watch butterflies dance in the warm breeze, and to soak in the peace of the moment.

I thought about the towns I passed through, the people I’d met, the unpredictable weather, and the joy of being untethered from daily life. No Zoom meetings, no carpools, no household chores. I relished the pace of cycling — fast enough to get somewhere, but slow enough to take in everything around me. I listened more intently, saw more clearly, and fully immersed myself in the present.

The trail did more than guide me from Pittsburgh to Cumberland. It connected me — to strangers who became dinner companions, to landscapes shaped by centuries of history, and to the vision of a coast-to-coast path that will one day stretch all the way to Puget Sound.

As I rolled into town and finally removed my helmet, I realized it wasn’t the end of the ride. It was the beginning of many more to come, one pedal revolution at a time.

Erin Gifford enjoys writing about road trips, outdoor recreation, and national parks. Her writing credits include The Wall Street Journal, National Geographic, Costco Connection, and AARP.org.

This article is featured in the July/August 2025 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now