Throughout his 70-year career, my father, John Fleming Gould (1906-1996), displayed a keen awareness of art and its effect on the people viewing his work. The early 1940s, especially, was a pivotal time in his career, where he produced thousands of art pieces. Many of those pieces were created for The Saturday Evening Post.

Gould graduated from Pratt Institute in Brooklyn, New York, in 1927. He was also accepted into the summer 1926 and 1927 Resident Artists programs of the Louis Comfort Tiffany Foundation in Oyster Bay, Long Island, which helped him get a foothold in the world of art.

He soon found a niche at the beginning of the 1929 Great Depression in the pulp illustration business. Illustrating proved to be lucrative during the Depression years as people stayed home and read extensively (there was no television then, of course). Gould illustrated some 15,000 pen and ink drawings for detective, Western, and adventure tales, including G-8 and His Battle Aces and The Spider’s Web stories.

In 1927, John Gould rented his first studio at 161 W 23rd St. in New York City. He shared it with Walter Baumhofer and several other artists.

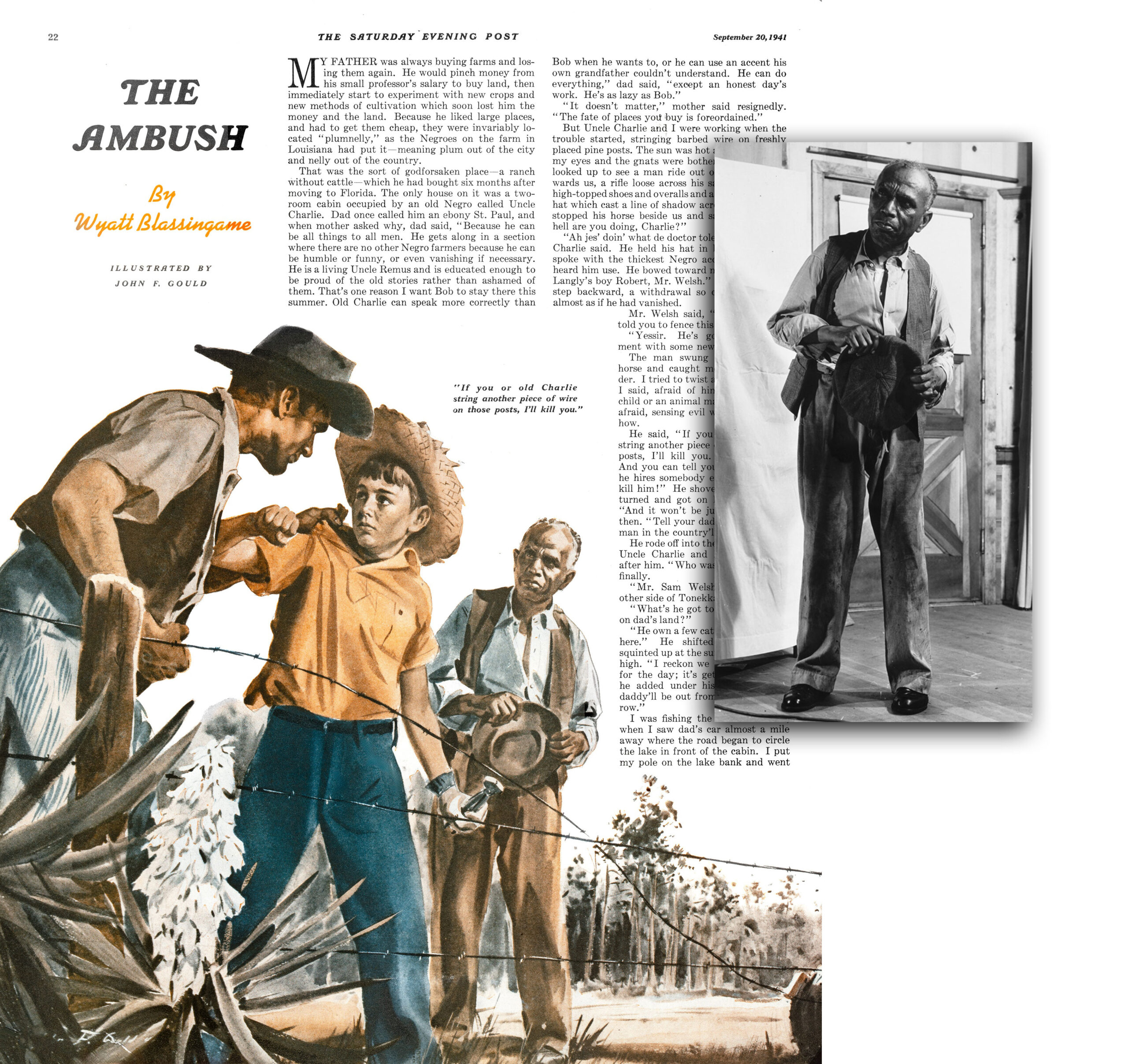

During the twelve-year period from 1929 to 1941, he always found time to make samples to show to prospective clients. The first illustration Gould did for the Post was “Song for a Handsaw” by Dorothy Thomas in their August 23, 1941, issue. It began a very exciting part of his professional career. There was always a blend of the words and pictures that gave the reader a true feeling of “being there” as the story unfolded. Facial expressions and body positioning were very important to him in conveying what the writer of the story was saying. You can’t help seeing how all the characters in the illustration below hold your attention, even the young girl to the far right. He would carefully photograph models and then use these images for reference in producing the finished artwork. Conversations usually occurred between Gould and writer to arrive at a clear and convincing picture.

My father’s career as an illustrator for the Post has revealed some truly fascinating stories about his associations with the writers. For instance, he worked with famed children’s writer Roald Dahl on his true story, “Shot Down Over Libya,” which appeared in the August 1, 1942, issue of the Post.

The Post story was authored anonymously for reasons of military security. Dahl had been flying for the Royal Air Force during World War II when his plane was shot down in the desert. He suffered serious injuries and months of blindness and was eventually sent to Washington. British novelist C.S. Forester encouraged Dahl to write about his own experiences as a fighter pilot. For my father, illustrating this story was a great accomplishment so early in his Saturday Evening Post tenure.

Many of the letters sent to my father by the writers of the stories revealed their enthusiasm for his illustrations. One such letter was from writer David Lamson for the story “A Girl Can Remember,” which appeared in the May 9, 1942, issue of Post. The letter from David appears below.

My father took an incredible amount of care in the portrayal and expressions of the people in the various scenes. He would often employ professional models for the characters in the illustrations, keeping a box of 8×10 black and white photos of models for reference from the John Robert Powers Model Agency. A teenaged Grace Kelly was one of the hundreds of photos in his collection.

An illustration that shows his particular care in how characters were portrayed is from the September 20, 1941, story “The Ambush” by Wyatt Blassingame. The finished page and model’s pose in the photo show his preparation for the painting. The photograph was taken in his studio behind our residence on Long Island, Queens Village, New York.

The Post years undoubtedly were a tremendous part of his artistic career and legacy.

His legacy also continues in part at the Norman Rockwell Museum in Stockbridge, Massachusetts. My father had retained possession of the original framed artwork for “Song for a Handsaw.” He very clearly marked on the paper backing, “This painting is not to be sold and is to remain in the family of my four sons, John, Robert, William, and Paul.” Well, you might be able to imagine the problems in shifting the painting around to four locations.

I contacted the museum in May of 2013, with the idea of having an exhibition of my father’s work. They suggested donating the original illustration to the museum. The curator at the time, Joyce K. Schiller, told me that over the last decade the Norman Rockwell Museum has made a commitment to collect more broadly in the field of American illustration art. So, in January of 2014, the Gould family donated the illustration, which is now in the museum’s permanent collection.

In early 1950’s while living in Cornwall, New York, my Dad wrote something that gave us yet another glimpse into his artistic process: “We are very fortunate to live in the area where Storm King Mountain and the Highlands of the Hudson dominate the scene with constantly changing color, tone and mood. As an artist I find reality a permanent challenge for artistic interpretation. Enjoying the visible world, discovering its beauty and communicating it to others through the medium of painting summarizes my philosophy of art.”

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

Thanks so much for this! I always enjoy looks into the professional lives of creative artists.

Thank you Bob. It was very exciting to compose this story.

Thanks for this in-depth feature on your Dad’s career as an illustrator; particularly the World War II aircraft!