For decades, plants have played a niche role in crime-solving, and some experts think their use as forensic tools should be greatly expanded.

Forensic botany, a branch of crime-scene investigation, first came to prominence during the 1935 trial of the man accused of kidnapping and murdering the baby of storied pilot Charles Lindbergh. A scientist proved through growth-ring analysis that wood found at the suspect’s home was used to make a hand-made ladder left at the crime scene, helping to ensure a conviction.

Moss is the focus of a study published on November 10, 2025. The authors call moss a “silent witness,” as it thrives in nearly all environments, tolerating floods, droughts, and extreme pH conditions from highly alkaline to strongly acidic. It will grow on any substrate, including stones (unless they’re rolling), wood, city sidewalks, buildings, human skeletons, you name it. In other words, moss is always watching us.

One of the neat things about moss from a crime-solving perspective is that it readily breaks into small bits that cling well to fabrics. The take-home there is that when a crime is committed outdoors, there’s a good chance the guilty party takes some moss home. And with around 12,000 species worldwide, moss can tie a crime to very specific areas.

But the study’s authors were dismayed to find that, after searching through 150 years of records, moss was used to solve just 11 murders. Cases ranged from 1929, when the thickness of moss on human bones let police determine how long the body had been there, to 2015, when moss helped fill in details about the scene of a suicide.

In a 2011 case, a man confessed to killing his daughter, saying her body was somewhere in a large region of northern Michigan. Fortunately, bits of moss from the man’s shoes were of a species that only grew in certain micro-habitats. It narrowed the location of the girl’s body down to an area measuring roughly 50 square feet.

The authors of that 2025 moss study said that plants, especially mosses, are potent yet underutilized forensic tools. One barrier to the wider use of forensic botany as a lack of training in law enforcement. Another hurdle is that identifying moss can be time-consuming, as is clear in a 2025 case where moss found with human bones that had been exhumed from graves and dumped in a heap helped pinpoint the spot where they had been dug up after much painstaking and time-consuming analysis.

In a strange twist, one type of moss has preserved the bodies of murder victims dating back to the Bronze Age. Dubbed bog bodies, they bear signs of stabbing, strangulation, and other violent ends. We have such details thanks to a clan of 300-ish moss species in the genus Sphagnum, variously called peat, sphagnum, or bog moss. Shaggy-looking and bright green, moisture-loving sphagnum moss is found mainly in the northern hemisphere on the tundra, in coniferous forests, and especially in peat bogs.

Sphagnum thrives on bog edges, where it slowly extends in a floating mat onto open water. Over time, moss can cover over a bog, forming a “waterbed” of moss that bounces when you walk on it. As the moss adds new growth each year, older parts at the bottom slough off into the water, where they release an acidic molecule called sphagnan that stops microbes from breaking down flesh. Dead moss fragments also strip the water of oxygen, which further limits decay. And finally, the humic acid in peat moss forces water from soft tissue, basically turning skin to tanned leather. Most bog bodies come to light when compressed peat, used as fuel, is dug from thick peat beds where sphagnum has filled in former bogs over millennia.

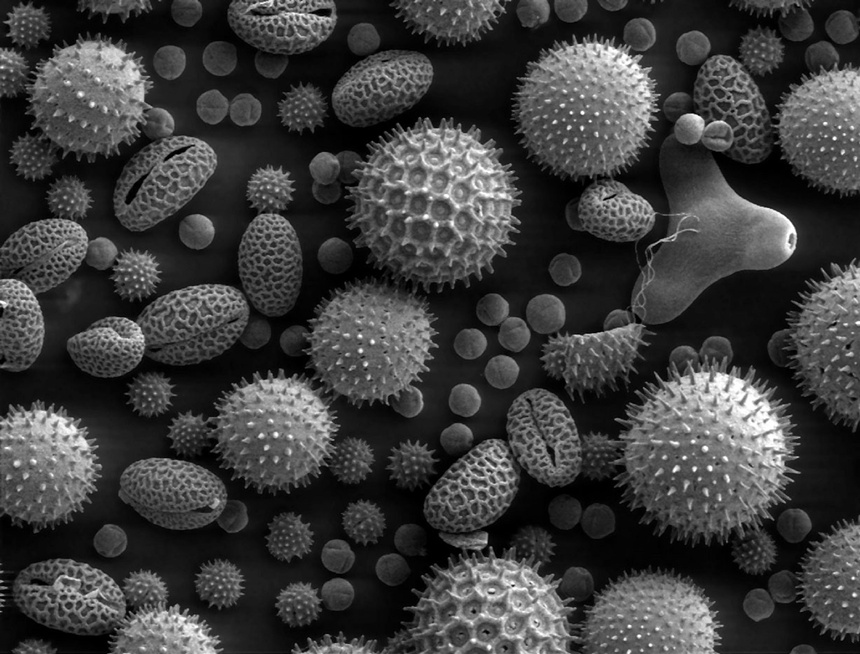

Another plant-based forensic tool that’s nothing to sneeze at is pollen, the male half of the equation in a flowering plant’s reproduction process. The microscopic size and typically barbed or spiked surface of pollen grains mean they go everywhere and stick to everything. Good luck washing pollen from natural-fiber fabrics like wool and cotton, because it may take a while.

Pollen’s other claim to fame is its extreme durability, thanks to an outer coat made of a uniquely tough polymer that can last for millions of years. Intact pollen grains are routinely found in fossil beds. These attributes spawned a field of science known as forensic palynology (Scrabble players take note).

When the decomposing body of a young girl surfaced in Boston Harbor in 2015, she remained “Baby Doe” until analysis of pollen from her clothing pinpointed the neighborhood she had lived in, and police were able to identify her and arrest two suspects.

In a 1993 Bridgend, England case, walnut pollen tied a murder suspect to the place he disposed of his victim. Even though there hadn’t been walnut trees in that area for thirty years, the pollen was still in the soil. But that’s nothing compared to what happened in Austria in 1959. Police in that case had a suspect with motive and opportunity, yet no body. But mud from the suspect’s boots had fossilized hickory-tree pollen grains dating back 20 million years, apparently from eroded sediment of a rock formation. There was only one place near Vienna where an outcrop of that age existed, and that’s where they found the body.

Maybe someday Netflix will try a series called Plant Scene Investigation. It would be great if author Michael Pollan could write the script, and Kate Moss take the lead role.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

My pleasure! Thank you for commenting.

After reading this new feature, I find myself in agreement with the experts in the first paragraph. Plants usage as forensic tools should be greatly expanded for crime solving.

The following paragraphs (and links) back it up further. As a ‘non-scientist’ I can follow along here pretty well. The section on pollen is nothing to sneeze at (in this regard) even though I’ve been sneezing A LOT with fall allergies, Paul. The weather’s been all over the place: back and forth hot to cold, like table tennis!

The cases solved here are quite impressive. Thanks for this report on them.