“To me, homesteading is the solution of all poverty’s problems.”

– Elinore Pruitt Stewart, Letters of a Woman Homesteader

After years of working for others, Elinore Pruitt Stewart longed to “Just knock about foot-loose and free to see life as a gypsy sees it,” according to her collected letters. That seems to explain why she left Colorado for Wyoming to file a claim as a homesteader.

Elinore Pruitt was born on June 3, 1876, on White Bead Hill, a settlement in Chickasaw Nation, Indian Territory (in what would later become Garvin County, Oklahoma). Her father died shortly after her birth, and her mother married her late husband’s brother. By 1894, Stewart’s mother and stepfather had died, leaving the 18-year old-responsible for raising five younger stepsiblings.

In 1902, Stewart, 26, married 48-year-old Harry Cramer Rupert, who later died in a railroad accident, leaving her pregnant with her daughter Mary Jerrine. After moving to Denver, Stewart became a nurse and housekeeper for Juliet Coney, a widowed schoolteacher from Boston. After reading an ad in the Denver Post from widower Henry Clyde Stewart for a housekeeper at his homestead near Burntfork, Wyoming, she became excited about the idea of “the mountains, the pines and the clean fresh air.” She applied for the job, and by March 1909, she and her daughter were traveling to Stewart’s remote homestead. “I was twenty-four hours on the train and two days on the stage, and oh, those two days!” she wrote Coney. “The snow was just beginning to melt and the mud was about the worst I ever heard of.”

Shortly after her arrival, she wrote her former employer that “everything is just lovely for me. I have a very, very comfortable situation and Mr. Stewart is absolutely no trouble, for as soon as he has his meals he retires to his room and plays on his bagpipe, only he calls it his ‘bugpeep.’” He played the song “The Campbells are Coming” so often, Pruitt joked, that “I wish they would make haste and get here.”

Determined to have land of her own, Elinore filed a claim for 160 acres adjacent to Henry’s homestead and wrote Coney she was “now a bloated landowner.”

“I have a grove of twelve swamp pines on my place, and am going to build my house there…I have all the nice snow-water I want; a small stream runs through the center of my land and I am quite near wood,” she wrote. She also built a 12×16-foot addition to Henry’s house as her own cabin. Curiously, in her letter she omitted mentioning that on May 5th she and Henry had wed. Years later she excused the lapse on having to “chink in the wedding” in the midst of “planting oats” and other spring farm work. In reality, she claimed her lot before she wed in an effort to be independent. However, since the Homestead Act demanded married women own government land only under their husband’s name, Stewart finally signed over her property to her mother-in-law in 1912 rather than risk losing it.

Between 1909 and 1914, Elinore Stewart wrote many letters to Coney praising Wyoming’s pristine beauty. Among them were vivid descriptions of the natural world. “There was a tang of sage and of pine in the air, and our horse was midside deep in rabbit-brush, a shrub just covered with flowers that look and smell like goldenrod,” she wrote the summer of 1909. In another letter she described how the shadows of the quaking aspens “dimpled and twinkled over the grass like happy children. The sound of the dashing, roaring water kept inviting me to cast for trout…”

Her letters also revealed the coy way she treated Henry. In September 1909, when local women invited her on a wagon trip to Utah to gather fruit, she asked his permission. When he refused, she deliberately “continued to look abused lest he gets it into his head that he can boss me.” Once he was reduced “to the proper plane of humility… and begged my pardon,” and told her to do what she wanted, she forgave him.

Other letters described how she and her friends helped those in need. On Christmas morning 1909 they planned to deliver food to a dozen men who tended sheep in twelve camps that were scattered across the mountains. After packing home-cooked roasts, sausages, jellies, bread, and desserts in sleds that were hitched to horses, they careened across the snow to the sheep herders’ camps. ‘It would have done your heart good to see the sheep-men,” she wrote. “They were all delighted, and when you consider that they live solely on canned corn and tomatoes, beans, salt pork, and coffee, you can fancy what they thought of their treat.”

Another letter told how an elderly set of grandparents who had raised their granddaughter from infancy now suffered so much from rheumatism and other ailments that they bought expensive remedies — “horrid patent stuff!” — which drained their savings. To help the teenaged granddaughter, Stewart and her friends donated fabric, sewed dresses, and bought shoes for the barefoot girl. When presented, with the gifts, the girl was so overcome that she began to cry in disbelief: “They ain’t for me. I know they ain’t.”

In addition to Jerrine, Stewart had five children with Henry, three of them sons who survived. As the pregnant Stewart wrote Coney in December 1912, “ You must think of me as one who is truly happy. It is true, I want a great many things I haven’t got, but I don’t want them enough to be discontented and not enjoy the many blessings that are mine. I have my home among the blue mountains, my healthy, well-formed children, my clean, honest husband, my kind gentle milk cows, my garden … the best kindest neighbors, my dear absent friends.”

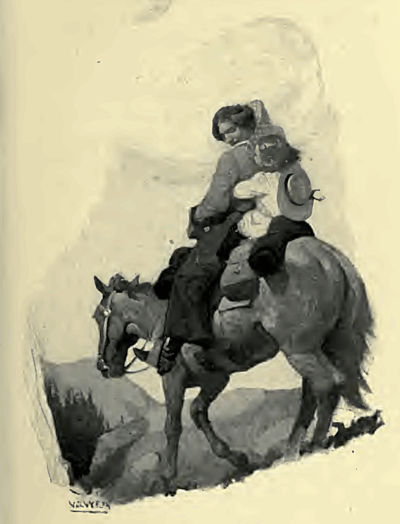

Coney, meanwhile, was so fascinated by Stewart’s letters that while visiting Boston she showed them to her friend Ellery Sedgwick, editor of The Atlantic Monthly magazine. After reading them, he published them in the magazine as a series between October 1913 and April 1914. Houghton Mifflin collected them in the 1914 book Letters of a Woman Homesteader, with illustrations by N.C. Wyeth.

The work was so popular that Sedgwick commissioned a second series of letters about Stewart’s subsequent experiences, which Houghton Mifflin re-published a year later as Letters on an Elk Hunt. In contrast to the first letters written so ingenuously to Coney, the second collection, according to Stewart’s biographer Susanne K. George, were intentionally “written for publication,” for “she was known to have ‘never let the facts get in the way of a good story.’”

By the early 1920s, Stewart was nationally known as the “Woman Homesteader.” She died October 8, 1933, at age 57 in Rock Spring, Wyoming after a gall bladder operation.

The significance of Letters of a Woman Homesteader according to Gretel Ehrlich’s foreword to the 1998 republication of the book is not the “breathtaking difficulties of solitude and struggle but about the way in which we might find plenitude in paucity. No other account of frontier life so demonstrates the meaning of neighborliness and community, of true unstinting charity, of tenaciousness charged not by dour stoicism but by simple joy.”

The Elinore Pruitt Stewart Homestead has been preserved and is listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now