On December 1, 1955, in Montogomery, Alabama, Rosa Parks took a seat in the front of the bus and refused to give it up when asked to do so. This act of defiance ignited a boycott movement and one of the early successful campaigns to challenge the Jim Crow system in the South. After 381 days of boycotts, racial segregation on public transportation was deemed unconstitutional, and Rosa Parks became a national hero.

Contrary to the myth, when Parks went on the bus that day on her way home from work, she wasn’t tired, but she did carry with her a bundle in her purse. Inside was a mustard-and-gray floral belted wrap dress that Parks was working on. At the time, she was employed as an assistant tailor for a department store downtown, but the dress was intended for personal use.

While the dress itself was more playful than the tweed dress-suit that Parks was wearing in her arrest image and that brought her into the spotlight, both adhered to the fashionable trends of the time, presenting a respectable and demure image. Parks’s arrest photo doesn’t show her in a disheveled state, but with her hair pulled back, wearing a small hat band with a net, dotted with pearls. By conveying this image, she was able to garner support for the civil rights cause.

The dress in Parks’s bag might seem irrelevant to the bigger story of the Montgomery Bus Boycott, but the fact that Parks was a seamstress is not a negligible detail in her biography. Unlike domestic work, the dressmaking trade offered a lucrative career for many Black women, providing them with autonomy and a venue to express their creativity. Dressmaking also provided a flexible schedule that allowed women like Parks to devote their time to activism.

Another notable Black dressmaker was Elizabeth Keckley, who was able to buy her freedom by using her skills to emancipate herself and her son. As a free woman with a profession, Keckley moved from St. Louis to Washington, D.C., where she gained many white clients, among them Mary Todd Lincoln.

Even after the abolition of slavery, dressmaking was seen as a profession that could advance more than one’s freedom. In 1893, the civil rights activist Mary Church Terrell called for the establishment of vocational education for girls in dressmaking and millinery (hat making), as a way to improve their social position and a means of racial uplifting.

As a seamstress, Parks was well aware of the power of clothes and appearance. Dressing up was not only an individual preference but a calculated strategy for many Black women to claim a sense of dignity and respect, even in the face of discrimination. According to historian Taylor Branch, Parks was “dignified enough in manner, speech, and dress to command her respect of the leading classes,” an appearance that was crucial to the boycott’s success. In subsequent photos of Parks after her arrest, she is seen carrying a black purse and white gloves, a popular marker for middle-class respectability in the 1950s. By presenting a demure and respectable appearance, Parks conveyed the righteousness of her plea for equality.

Parks was not the only one who invested in presenting a fashionable appearance. Young activists from Diane Nash to Anne Moody understood that fashion was an important means for Black women to claim access to the privileges of respectable femininity, and they used it as a tool in their struggle for civil rights. When they participated in marching, protesting, and sit-ins, Black women insisted on wearing their “Sunday best” — crisp, neat clothes and pressed hair — seeing it as a political statement of defiance against racist stereotypes that views Black people as dirty and unkempt.

Dressing “nice” was not just a political tactic, however. Investing in one’s appearance and clothes also offered a sense of pleasure and self-expression that appealed to many women. Indeed, the dress that Parks carried on the day of her arrest was a testament for such sentiments. By investing her time and creativity to make something for herself, Parks may not have seen fashion as a frivolous endeavor, but a radical act of self-care.

Although by the 1960s many in the civil rights movement increasingly adopted more casual styles, the importance of fashion and appearance continued to play a role in the movement’s politics, in particular through the slogan “Black is Beautiful.” Through the adoption of Afros, African prints, and dashiki-style shirts, Black women reclaimed their culture and African heritage as a source of pride, using the style as a public act of defiance against White beauty standards.

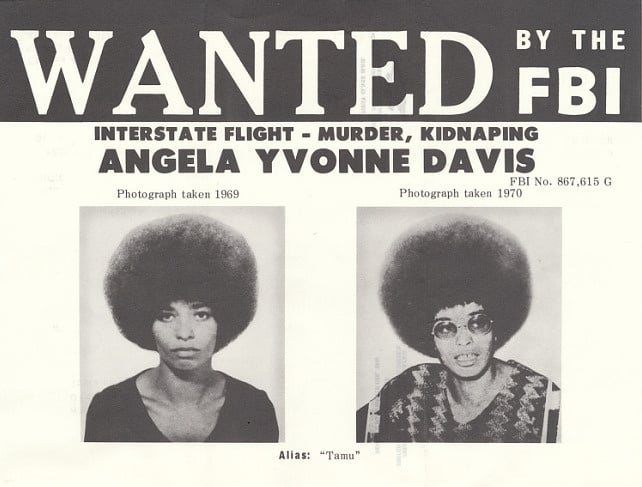

Angela Davis, in another photo that became iconic, epitomized the look with her halo-shaped Afro, an African dashiki, and see-through sunglasses. The large Afro became so identified with Davis that it became a trademark not only of her activism, but also of a new image of Black beauty.

If Davis and Parks presented very different images of Black femininity, their understanding of the role of clothing and appearance in the struggle was the same. Fashion was a political tool to claim respectability, power, and public support. But first and foremost, it was a tool of pleasure, self-expression, and personal pride — one that could not be taken away.

Even if Parks never got to wear the dress she made for herself, it was important enough for her to keep it as a reminder of her courage and determination. By claiming her right to enjoy fashion, Parks also claimed her humanity and dignity in the face of racism, taking a stand by insisting to sit down.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now