Born in Rostov-on-the-Don, Russia, to wealthy parents Ivan and Izabella Alajálov, Constantin Alajálov (1900-1987) grew up a well-educated man. He attended the Gymnasium of Rostov from 1912 to 1917 and began his studies at the University of Petrograd in 1917. At five years old, the artist began making sketches; a talent his mother nurtured. In school, he preferred languages. Alajálov studied French, English, German, and Italian. His skill in art and language became tools for survival before ever turning it into a passionate career.

His academic pursuits were cut short in 1917 on the advent of the Russian Revolution. The revolution began with an armed insurrection in Petrograd, the very city in which Alajálov was studying. Forced out of school, the Bolsheviks drafted Alajálov to produce political propaganda throughout southern Russian villages. He painted wall murals and posters until escaping to Rasht, Persia (now northern Iran) in 1920.

Constantin’s time in Persia, however, was short-lived. In 1921, the khan he was working for was executed by his successor. Again, Alajálov fled to a new land and sought refuge in Constantinople (modern Istanbul, Turkey).

Alajálov’s Constantinople era was one of abject poverty. The artist was grateful for a glass of goat’s milk or a small meal as payment for posters and murals. He once remarked that Russian princes wandered the streets in gray flannel pajamas provided by the American Red Cross. He began a Russian Artists Club to study technique and critique the work of his peers. After two years, Constantin had saved enough money, $100, to make the trip to New York City.

Arriving in 1923 with $5 in his pocket, the artist ran into a boyhood friend on Broadway. The friend happened to be the secretary of famous American dancer Isadora Duncan. Constantin used this connection to network with the Russian community in New York City. Soon the artist was painting murals and posters again. His artistic “big break” arrived when he was hired to paint the interior of the Bi-Ba-Bo Club. The club was a popular nightlife spot due to its owner, high-society socialite, Russian countess Anna Zarenkau.

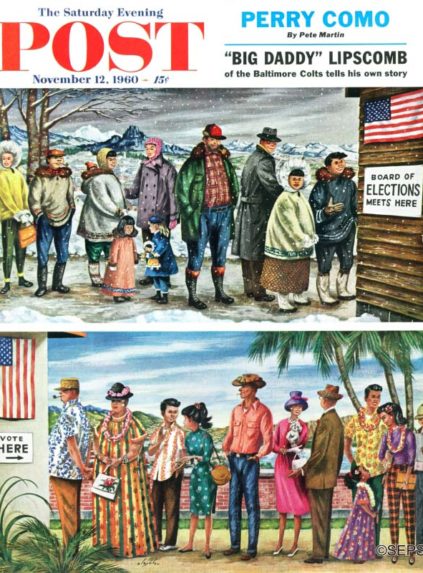

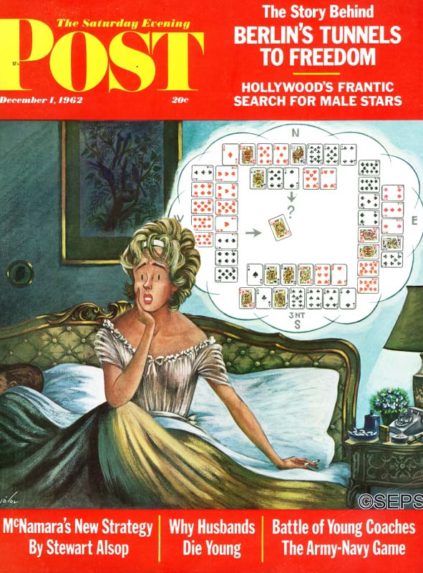

Three years later, at age 25, The New Yorker accepted his submission for the magazine's September 25, 1926, cover. His covers were satirical commentaries on American life; his artistic style experimental. Alajálov’s art was both Realist, and Cubist. Some of his works contain thick outlining reminiscent of Picasso’s early primitive style.

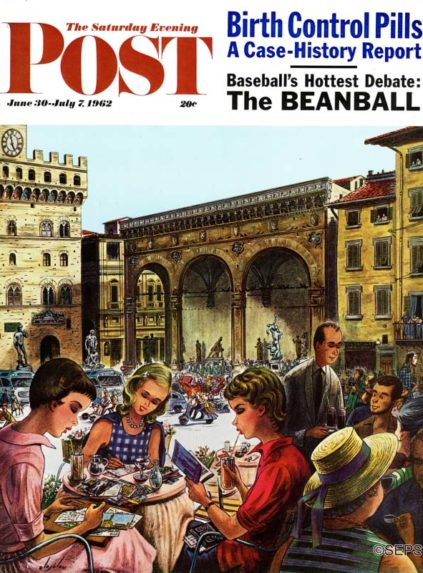

During his exclusive contract years (late 1920s to 1930s) with The New Yorker, Alajálov taught at The Phoenix Art Institute and Alexandre Archipenko’s Ecole D’Art (both in NYC). He also became the director of the Societe Anonyme for the Museum of Modern Art. During this fruitful time, the artist traveled the world visiting museums and studying art, composition, and technique. He visited Haiti in 1929, Cuba in 1933, Italy in 1938, Honolulu in 1939, and spent the majority of his summers in either Paris or on the French Riviera.

His first Post cover illustration appeared on October 6, 1945. By this time, Constantin Alajálov had made quite a name for himself in the commercial illustration industry. He had already provided cover work for magazines such as Vanity Fair, Town and Country, Fortune, Life, Harper’s Bazaar, Vogue, and House & Garden. His work was so sought after that he was placed in the unique situation of overcoming traditional contract exclusivity between The New Yorker and The Saturday Evening Post.

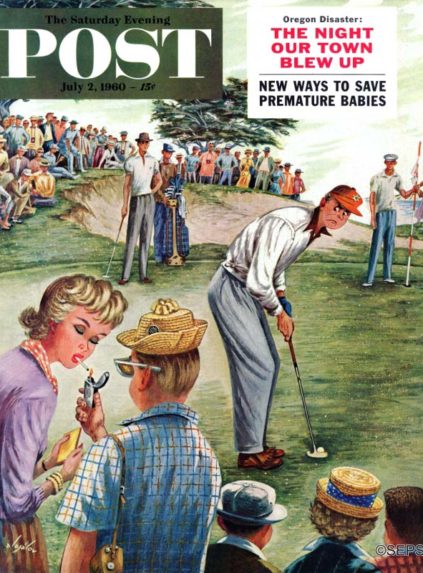

Constantin Alajálov lived a life filled with adventure, travel, ups, downs, failures, and successes. He rose from Russian revolutionary refugee to the heights of the New York art world. He was a global citizen, having traveled much of the world before the middle of the 20th century. His extensive travels were a feat for the time period. In retirement, Alajálov enjoyed swimming, horseback riding, tennis, piano, and golf. He died of natural causes at the age of 87 in 1987.