The Premier Pantomime Cartoonist

If you looked at a newspaper or magazine cartoon in, say, the 19th century, it might seem a little … off. The illustrations were packed with pen strokes, and captions were often comprised of two to four lines of wordy dialogue, resulting in the effect of a short conversation between two sketched characters.

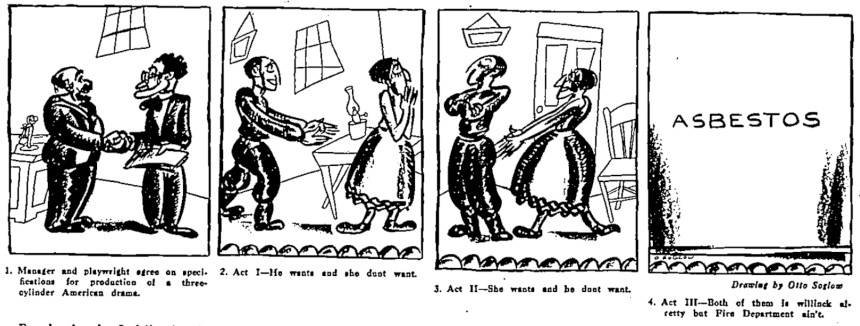

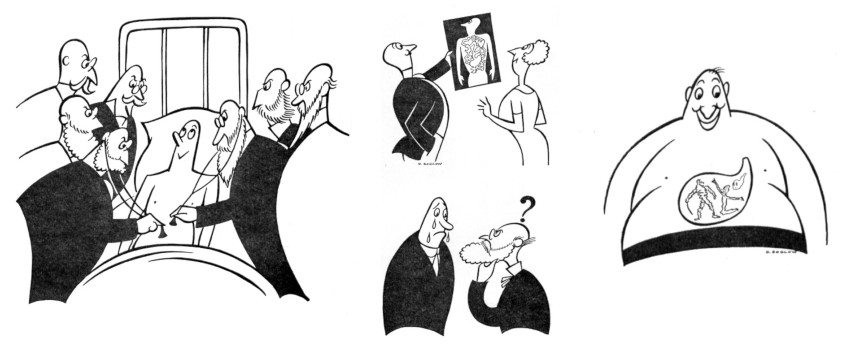

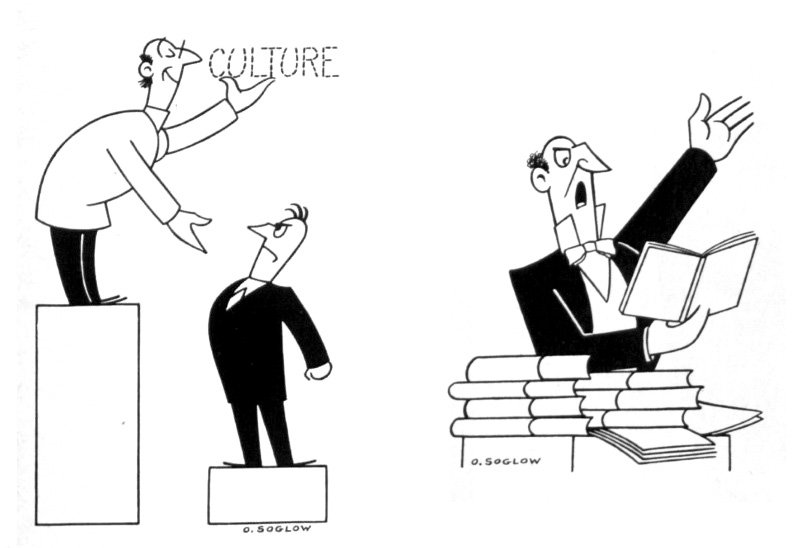

One of the cartoonists responsible for upending this style — and pioneering the kinds of strips we know today — was Otto Soglow, born on this day in 1900. At The New Yorker and, later, in this magazine and newspapers across the country, Soglow pared down lines in his illustrations, presenting a clean, minimalist rendering of whimsical characters. In the way of captions, uniquely, he often used very few or none at all, making a name for himself as a pantomime cartoonist with his popular strip The Little King, which ran for almost 40 years.

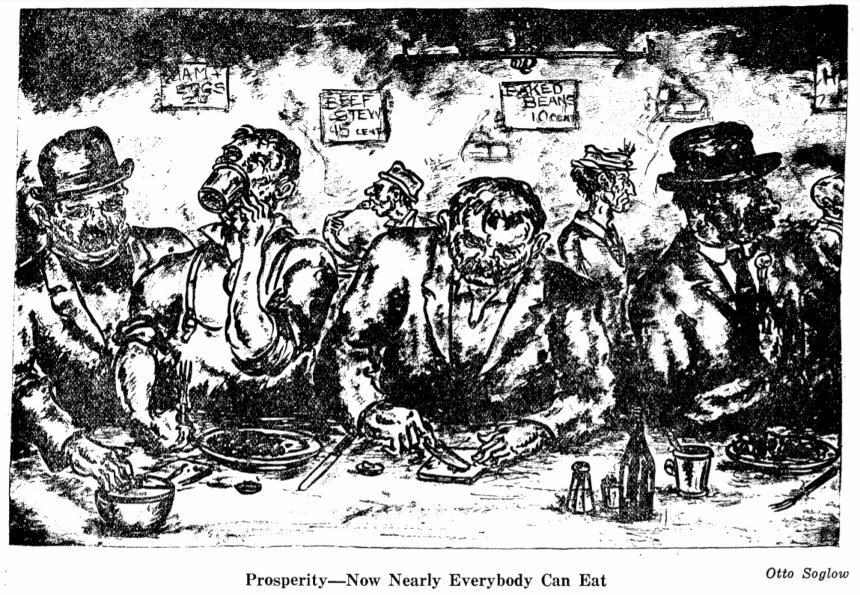

Soglow didn’t set out to become a cartoonist. A passionate performer, he dropped out of high school to pursue a career in acting. He worked as a shipping clerk, a packer, and even as a baby rattle painter before taking up illustrating professionally. In the 1920s, Soglow drew toons for the pages of radical New York publications like The New Masses and The Liberator. Influenced by the politics and aesthetics of the Art Students’ League, his work during this time depicted gritty cityscapes, working-class scenes, and socially-conscious themes.

In the August 1922 issue of The Liberator, which had published one of Soglow’s earliest illustrations the month before, the editors apologized for neglecting to credit him, saying “Soglow is to give the Liberator more of his strong work, so full of atmosphere, poetry, and sensitive observation.”

By the late ’20s, he was publishing toons and small illustrations in The New Yorker, alongside names like Peter Arno, Helen Hokinson, and James Thurber. In the magazine’s obituary for Soglow, the author noted that while his style was once busy with ink, it became purer over the years, eventually omitting all details except the most necessary: “There was nothing to distract the eye or the mind.” The New Yorker was also where Soglow introduced his most famous and enduring character: the little king.

In various weekly adventures for more than 40 years, Soglow’s “cartoon monarch” stumbled through silent, playful scenarios at the perplexity of his royal court. Far from a stereotypical depiction of a severe ruler, Soglow’s childlike king displayed no interest in power, but rather enjoyed simple pleasures like ice cream and zoo animals. While his barrel-chested guards smoked cigars, the short stubby sovereign blew bubbles out of a toy pipe. Soglow’s sight gags in his Little King strips — which were syndicated in papers around the country from 1934 to 1975 — were endearing nods to our better, more innocent, angels.

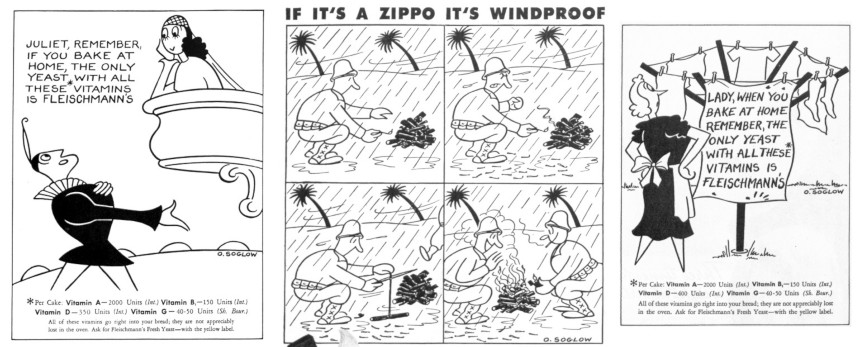

In taking his cartoons to a larger audience, the once-socialist Soglow struck a deal with newspaper magnate William Randolph Hearst. If this move wasn’t quite contradictory, his career quickly took a commercial turn as he began illustrating ads for Realsilk socks, Mutual Life Insurance Company, Fleischmann’s Yeast, Pepsi-Cola, oil companies, and others. His ads — of course, lacking the quaint charm of his other work — appeared in The Saturday Evening Post for decades. Soglow was also a staunch supporter of the war effort, designing propaganda posters and supporting art programs for soldiers.

Although he likely made a great deal of money illustrating and cartooning, Soglow never lost his desire to perform. New York newspapers in the ’30s and ’40s described him as a hit at parties, giving impersonations and magic tricks that rivalled Chaplin’s. Given his earlier penchant for the poetic and the critical, discerning audiences might be tempted to read some semblance of subtle geopolitical commentary into The Little King, but Soglow said that was baseless and “just plain silly.” As for the origin of the beloved character that graced funny pages for decades, he gave no deep, revelatory explanation; “He just happened.”

Soglow drew The Little King until he died in 1975. Although he isn’t remembered widely by the populace, the cartoonist is decidedly among the ranks of important New Yorker illustrators, and the magazine still uses his artwork in print and online. In a review of a new Little King coffee table book in 2012, Jeet Heer called Soglow “one of the central cartoonists of mid-century America.” Flipping through the comics of any paper in the country before and after Soglow, it would be difficult to disagree.

“Who Says I’m Uncultured?”/ “Let’s Keep the Filibuster,”The Saturday Evening Post, June 16, 1962, July 14, 1962

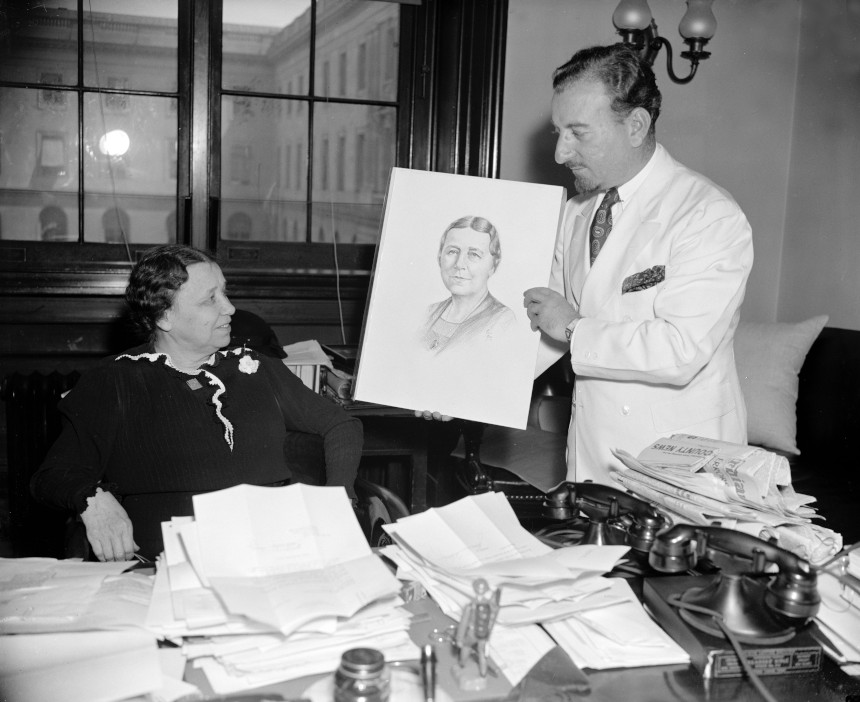

Mrs. Caraway Goes to Washington

The first woman elected to the U.S. Senate is not a household name. That woman, Hattie Wyatt Caraway of Arkansas, kept a very low profile. She is not considered a political trailblazer. Indeed, she voted with the rest of the Southern delegation against the Anti-Lynching Bill of 1934, intended to make lynching a federal crime. But though her name has become a historical footnote, Caraway, who was born in the shadow of post-Civil War Reconstruction and died at the dawn of the atomic age, offers a fascinating study in the challenges facing women in American politics.

Caraway won a special election to the Senate in 1931 after the death of her husband, Democratic Senator Thaddeus Caraway. This was not without precedent for a politician’s widow, because the move allowed the “real candidates” — the men — time to prepare their campaigns. But Caraway, at age 54, shocked the powers-that-be by announcing her plans to run in the 1932 general election.

In making the decision to run for a full term in the Senate, she knew she was breaking new ground for women. Until Caraway’s election, only one other woman had even set foot in the Senate, the self-styled “World’s Most Exclusive Club”; in 1922, 87-year-old Rebecca Felton had been allowed to sit in the chamber for a day as reward for her political contributions in Georgia. Though the 19th Amendment guaranteeing American women the right to vote had been ratified, the idea that government was a man’s sphere had not changed much since abolitionist and women’s rights advocate Sarah Grimké visited the U.S. Supreme Court years earlier in 1853. After Grimké was invited to sit in the Chief Justice’s chair, she stated that someday the seat might be occupied by a woman. In response, “the brethren laughed heartily,” she later recounted in a letter to a friend.

A widespread criticism of Caraway as she entered the 1932 campaign was that she was needed at home to take care of her children, even though they were already grown.

But in 1932, the year the Dow Jones hit its lowest point during the Great Depression, few Americans were laughing. Caraway, a small woman who always dressed in black after her husband’s death, could have easily passed as someone’s visiting grandmother in the halls of the Capitol. Her only previous elected experience was serving as the secretary of a small-town women’s club. But desperate constituents in Arkansas didn’t seem to care who she was, as long as she could help them.

Letters poured into Caraway’s Senate office, pleading for relief. As she read them and observed the action — or inaction — of fellow senators, she came to a startling revelation: Wasn’t a person — any person, even a woman — of moderate intelligence who worked hard, cared about average people, and stayed awake at their Senate desk (many colleagues didn’t) just as useful as those who made bombastic speeches?

Caraway’s three sons, West Pointers and high-ranking Army officers, supported her political aspirations. As she wrote in her journal entry of May 9, 1932, the first time she announced her decision to run: “Well, I pitched a coin and heads came three times, so because [my sons] wish and because I really want to try out my own theory of a woman running for office, I let my check and pledges be filed. And now won’t be able to sleep or eat.” Within two days’ time, though, Caraway seemed to have made peace with the decision, writing in her journal that she would “have a wonderful time running for office” if she could hold on to her dignity and sense of humor. During the campaign, she would need both.

A widespread criticism of Caraway as she entered the 1932 campaign was that she was needed at home to take care of her children, even though they were already grown. Sexism aside, Caraway’s campaign faced another problem: She had no money to run. But she did have a good friend in the flamboyant Louisiana politician Huey Long.

Long genuinely liked Caraway after spending time sitting next to her in the back row of the Senate, and he didn’t have much to lose by throwing his support behind her. Even if Caraway lost, it would not really be considered his fault since the odds were against her winning anyway. But if he were to help her get elected, he would emerge as a political miracle worker, and maybe even secure a rubber stamp for his pet programs. At the very least, he’d gain some ground in his power struggle with Arkansas’s other Senator, Joe T. Robinson.

With Long’s support, Caraway did win the 1932 election for a full term in the Senate, earning more total votes than all six men who ran against her put together. Some political observers said she would not have won without Huey’s help, but she notably defeated her opponents in counties where she and Long did not campaign.

In office, Caraway was dubbed “Silent Hattie” because she rarely delivered the thunderous orations her male colleagues were known for. It should be noted that there were male senators who declined to make speeches as well, but it was Caraway whose silence was labeled.

If she was quieter than most, her record spoke for her. As a senator, she worked tirelessly, earning a reputation as an effective public servant in the troubled times of the Great Depression and World War II. A saying among Arkansans became, “Write Senator Caraway. She will help you if she can.”

Caraway did her best work in committee, where she could speak normally without having to orate from the well of the Senate chamber. In this small setting, she could work to convince others of what average people needed, like flood control. She had seen the devastation in her state when roaring waters washed away entire communities during the Great Flood of 1927, the most destructive flood ever to hit the state and one of the worst in the history of the nation.

In office, Caraway was dubbed “Silent Hattie” because she rarely delivered the thunderous orations her male colleagues were known for.

When Caraway first ran for office, she ran on the premise that the nation could be served by an average person who knew the price of milk and bread, and who remembered there were people who had none. She walked her talk, carrying her lunch in a brown paper bag, and starting each day by reading every word of the Congressional Record. She never missed a Senate vote or a committee meeting. Nor did she take time away from Congress to campaign, as others did.

In time, she proved to herself that she had a mind as good as anyone’s in the Senate. While serving on the Senate’s Agriculture Committee, for instance, something that was important to her rural state, she realized that she knew firsthand about issues that affected farmers more than what she called in her journal the “manicured men” of the Senate.

The voters of Arkansas, in turn, stood by her. Caraway was reelected in 1938, defeating a strong candidate whose campaign slogan boomed “Arkansas Needs Another Man in the Senate!” She therefore became not only the first woman to be elected to the Senate, but also the first to be reelected. Among her many firsts serving in the Senate from 1931 to 1945, she also became the first to preside over the Senate, chair a Senate committee, and lead a Senate hearing.

But it wasn’t easy being the only woman in the room. Caraway was often ignored by her fellow senators, and she had no mentor. Her position must have often felt insecure. Arkansas’s other senator, the powerful Joe T. Robinson, had very few interactions with her. She presumed it was because he was waiting for a “real” senator — a man — to arrive. Several of her journal entries reflect their terse relationship. On January 4, 1932, soon after Caraway entered the Senate, she wrote that Robinson “came around only for a moment at the instigation” of his chief-of-staff. On May 19, 1932, Robinson inspired her to write, “I very foolishly tried to talk to Joe today. Never again. He was cooler than a fresh cucumber and sourer than a pickled one.” Reflecting on their strained relationship, she once poignantly confessed in her journal, “Guess I said too much or too little. Never know.”

If she felt invisible in the Senate chambers, she was very aware that the press held her in the spotlight. At one point, she wrote in her journal, “Today I almost made the front page as I lost the hem out of my petticoat.” But Caraway didn’t view herself as a firebrand. Rather, she conducted herself as she believed a “Southern lady” would do. In her journal, she notes that she did not appreciate when a reporter “pushed into” her office. “I was terribly indignant,” Caraway wrote. “She got no interview.”

Still, in 1943, she notably cosponsored the Equal Rights Amendment, a piece of legislation that had already been introduced in Congress 11 times and failed each time. The proposal simply read, “Equality of rights under the law shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of sex.”

Caraway was also one of the sponsors of what has been called the most momentous piece of legislation in American history, the Servicemen’s Readjustment Act of 1944, popularly known as the GI Bill. In doing so, she put herself up against powerful congressmen who condemned the bill for being “socialist.” But Caraway, who came from a struggling farm family herself (she had only been able to go to college thanks to the generosity of a maiden aunt), firmly supported the piece of legislation, which contained educational benefits for World War II veterans. She saw it as a manifestation of her belief that education was the key to progress.

By 1944, however, Caraway’s style no longer resonated with voters in the same way. During her bid for reelection, she placed fourth in the Democratic primary. The winner, J. William Fulbright, a wealthy former Rhodes scholar, went on to secure the general election and would serve as a powerful force in the Senate for the next 30 years.

On Caraway’s final day in the Senate in 1945, her years of service earned her the rare standing ovation by her all-male colleagues. Yet, even as they honored her, a statement — which was no doubt meant as a compliment — offers a telling window into what it was like to be the first. “Mrs. Caraway,” one of the men proclaimed, “is the kind of woman senator that men senators prefer.”

More than a half-century after Caraway’s death in 1950, the challenging reality of her precarious position as the first woman to break into the “World’s Most Exclusive Club” still resonates. A few years ago, I was sitting next to Arkansas Senator Blanche Lincoln at a speaking engagement when the Senator opened her daily planner. Inside the front cover, where she would see it immediately, Senator Lincoln had written the words Caraway had written in her diary when she decided to run for the first time: “If I can hold on to my sense of humor and a modicum of dignity I shall have a wonderful time running for office, whether I get there or not.”

Nancy Hendricks writes extensively on women’s history and is the author of Senator Hattie Caraway: An Arkansas Legacy.

Originally Appeared at Zócalo Public Square

This article is featured in the November/December 2020 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Featured image: Library of Congress

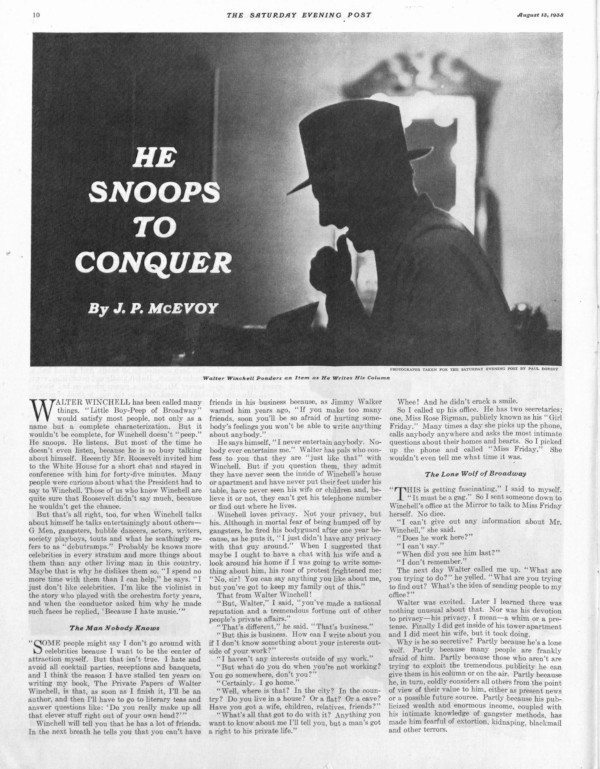

Walter Winchell: He Snooped to Conquer

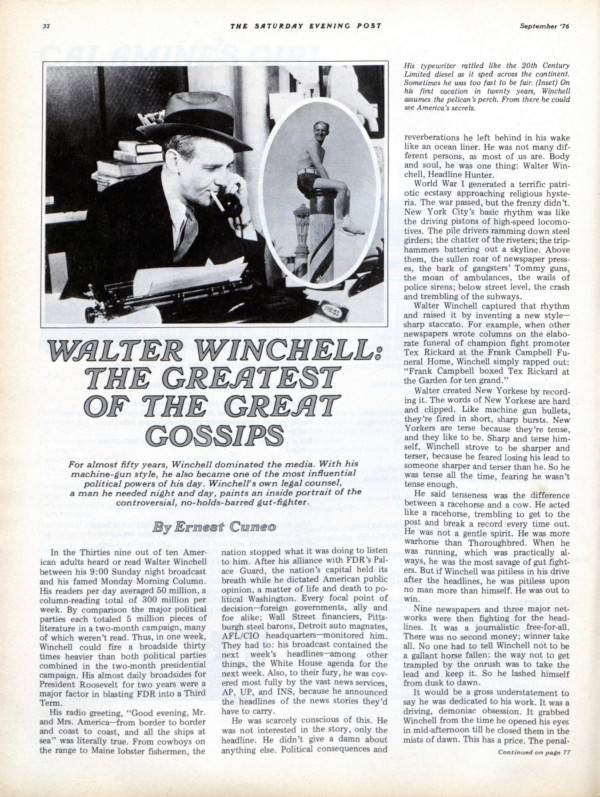

If he is remembered, the journalist and radio man Walter Winchell evokes a few different types of memories. Baby boomers might recall the narrator of the 1959 series The Untouchables. Their children might have caught the HBO biopic Winchell that starred Stanley Tucci as the fedora-donning gossip columnist. Younger people likely won’t recognize the name Walter Winchell at all. But consider this: every time you guiltily click on a link promising a juicy scoop on a washed-up actor, Winchell is somewhere, smiling.

In his heyday, Winchell commanded a collective audience of about 50 million Americans — two-thirds of the adult population in the 1930s. As biographer Neal Gabler claims in American Heritage magazine, anyone walking the streets on a warm Sunday evening in any city in America at the time would hear Winchell’s staccato voice through successive open windows on their way, giving updates on the war in Europe or a famous couple who might be “infanticipating.”

Making and breaking celebrities and politicians in his syndicated columns and radio broadcasts, Winchell built a complicated legacy. Though he often leveraged his platform to give a voice to everyday Americans, Winchell’s lifelong quest for popularity became his own undoing.

A new PBS American Masters documentary, Walter Winchell: The Power of Gossip, offers viewers a new look at how, for better or for worse, Winchell created “infotainment.” The documentary tracks the gadfly’s rise during the Great Depression and his slow decline in the McCarthy era, with Whoopi Goldberg as narrator and Stanley Tucci reprising his role as Winchell.

Director Ben Loeterman says that he was drawn to Winchell’s story as a sort of explanation of the current state of news media: “I think understanding the origins of how news is shaped and delivered and the importance of story, that has become absolutely part of journalism today, started in that sense, I think, with Walter Winchell.”

Winchell’s career arc can be simply understood with his own words: “From my childhood, I knew what I didn’t want: I didn’t want to be cold, I didn’t want to be hungry, homeless, or anonymous.”

In his early years reporting Broadway gossip at Bernarr Macfadden’s New York Evening Graphic (a tabloid commonly called the “Porno-Graphic”), Winchell learned that “the way to become famous fast is to throw a brick at someone who is famous.” He quickly made enemies, namely the Schuberts, who banned him from their theaters. Winchell secured a hefty readership, though, with his euphemistic claims about Jazz Age New Yorkers. Soon enough, he was rubbing elbows with Ernest Hemingway, Al Capone, and plenty of others who feared and respected his power of the press. He regularly attended Manhattan’s Stork Club, where anyone who was anyone knew to find him.

J.P. McEvoy turned a journalistic eye onto Winchell and his brand of “personal journalism,” writing the profile “He Snoops to Conquer” in this magazine in 1938. “Because he was fearless, talented, tireless and tormented by an unappeasable itch for success,” McEvoy wrote, “he arrived at his present peak — where he lives in a state of ingenuous surprise that he has arrived and a gnawing fear that he cannot remain.” Winchell was making about $300,000 a year at the time, between movies, radio, and his column at the Daily Mirror, which was syndicated to thousands of papers across the country. He had become famous for, among other things, coining provocative slang many called “New Yorkese.” H.L. Mencken, in The American Language, noted Winchell’s introduction of several words and phrases into the lexicon. Reno-vated (divorced), obnoxicated, Hard Times Square, intelligentleman. A young couple might be cupiding or “makin’ whoopee.”

Winchell’s reports weren’t limited to celebrity gossip, though. He was an early, outspoken critic of Nazism, taking shots at Hitler as a “homosexualist” called “Adele Hitler” (“he put a hand on a Hipler … ”) and regularly blasting antisemitic Nazi propaganda. When a German-American man named Fritz Kuhn began rallying Nazi sympathizers, first in the Friends of New Germany and later in the German-American Bund, Winchell found a nearer target for derision (“the SHAMerican”). Kuhn thought of himself as a sort of “American Führer,” organizing youth camps and rallies with the growing Bund in the ’30s. Right before more than 20,000 Nazis and Nazi sympathizers descended on Madison Square Garden in 1939 for George Washington’s birthday, Winchell tore into “the Ratzis … claiming G.W. to be the nation’s first Fritz Kuhn … There must be some mistake. Don’t they mean Benedict Arnold?” Winchell was delighted when Kuhn was sentenced to prison for embezzlement that year, writing about how the warden would be “the chief sufferer.”

At the start of President Roosevelt’s first term, Winchell praised the president as “the nation’s new hero,” sparking a close relationship with the administration that would prove fruitful for both of them. Years later, Post editor and former Roosevelt liaison Ernest Cuneo wrote all about how prominently Winchell had figured into their strategy to get FDR a third term (“Look, Walter,” I wanted to say, “you are the Third Term campaign.”).

Winchell was taken with President Roosevelt — and perfectly happy to act as a patriotic mouthpiece for the New Deal and American intervention in the war — but after Roosevelt left office, the gossip reporter found himself politically stranded. In 1951, Winchell affronted African-American performer Josephine Baker when he failed to defend her allegations of racism at his beloved Stork Club. Then, in 1954, he frustrated public health efforts by incorrectly announcing on his broadcast that a new polio immunization “may be a killer,” contributing to a dangerous anti-vaccination backlash. Winchell was really sunk, however, after he aligned himself closely with Joseph McCarthy and Roy Cohn.

“If he thought there was a star he could hitch himself to,” Loeterman says, “that was more important than the politics or any of the rest of it.”

Winchell transferred his disdain for Nazism into the anti-Communist witch hunts of the ’50s. He had vocalized his opposition to communism throughout his career, but McCarthy and Cohn made him an honorary member of a new — doomed — club. As Gabler put it, “he would lose because his populism had transmogrified into something cruel and unmanageable, just as his detractors had charged. Once a lovable rogue, Walter Winchell had become detestable.” He had brief stints on television in the ’50s, but nothing stuck. Winchell’s newspaper and radio routines were things of the past, and he had cultivated too much public distrust.

Although he faded from the public eye, Winchell’s mark was already made: the “welding” of news and entertainment. Two years after his death, People magazine was launched, and no shortage of commentators and gossips have haunted our screens and papers since. Kurt Andersen wrote in the Times about the evolution of Winchell’s personal journalism, “As star columnists leveraged their columns to accumulate personal celebrity and their personal celebrity to generate more readers, the market for their sort of journalism grew.”

If Winchell isn’t remembered, then he ought to be, if only so that we can more clearly understand that clickbait has a snappy, five-foot-seven predecessor who was one of the most famous men of his time.

Featured image taken by Paul Dorsey, The Saturday Evening Post, August 13, 1938

Saturday Evening Post Time Capsule: October 1938 – Aliens and Fascists

See all Time Capsule videos.

One of the illustrations by Henrique Alvim Corrêa for the original publication of H.G. Wells’ The War of the Worlds (1906)(Public Domain Review)

The Centennial of Mickey Rooney, America’s Most Persistent Performer

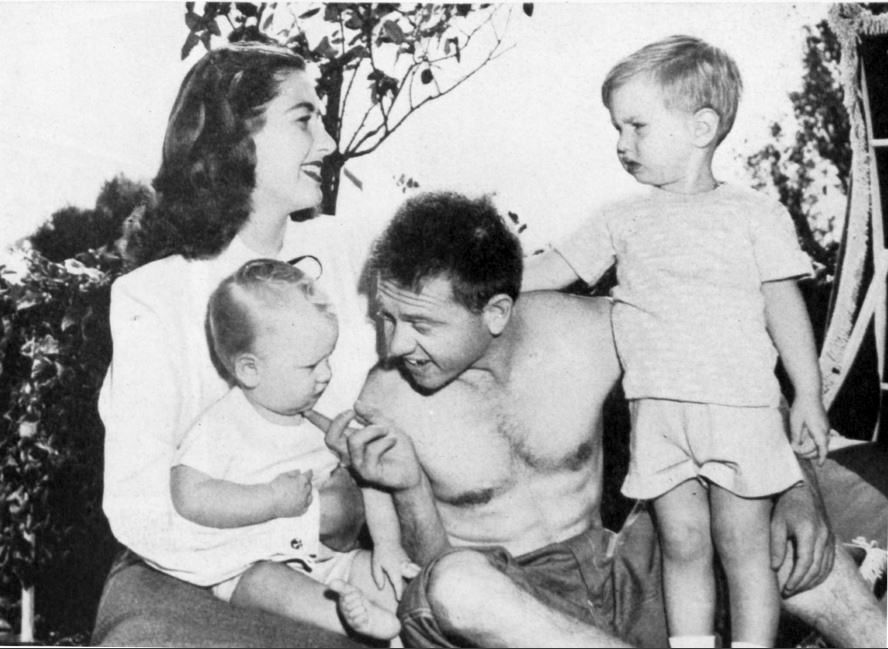

Today is the centennial of the birth of Mickey Rooney, the once-golden boy of Hollywood with likely the longest-running career of any American (or otherwise) film actor.

After beginning his lifelong stint in show business in a specially-tailored tux in his parents’ vaudeville shows at 15 months old, Rooney landed his first film role at age 6 and didn’t stop until 2014, the year he passed away.

The America of Rooney’s films at the height of his celebrity – when he played the lovably well-intentioned troublemaker Andy Hardy in 16 movies – was The Saturday Evening Post’s America: one with a freshly-ironed moral fabric and joyful endings. In fact, Rooney was a Post boy. As the Post bragged in a short piece in 1942, the actor won a medal at age 13 for selling magazines door-to-door and even at the studios where he made his Mickey McGuire movies: “Andy Hardy, as portrayed by Rooney, more often than not engages in financial enterprises that backfire, but in real life Rooney got away to a fast business start with no adolescent detours.”

The Post’s coverage of Rooney wasn’t always so laudatory, however. By 1962, he was just another example of “moral decay in America” as an editorial shone light on his multiple nasty divorces and thousands in back taxes. “Nothing in this sad story surprises us, Hollywood being the way it is,” the Post printed, “but we remember Andy Hardy.”

The now-familiar arc of the innocent child star becoming a frighteningly flawed adult perhaps began with Rooney’s departure from the saccharine cinema of the Hardy family into the trappings of wealth and fame. But he couldn’t play Andy Hardy forever, and he didn’t want to.

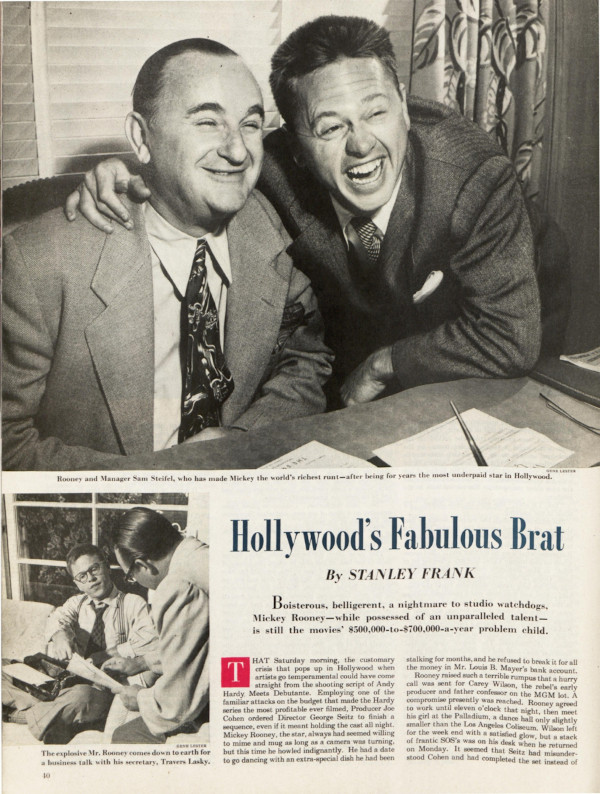

In 1947, the year after Rooney’s last film as Andy Hardy (with the exception of the 1958 revival), the Post published a lengthy profile of the actor called “Hollywood’s Fabulous Brat.” Rooney had spent three years – 1939, ’40, and ’41 – as the biggest box office draw in Hollywood, and he had a reputation for being belligerent, on the set and off. He was also seeking more substantial work.

“I’ll never make another Hardy picture,” he told the Post, incorrectly. “I’m fed up with those dopey, insipid parts. How long can a guy play a jerk kid? I’m 27 years old. I’ve been divorced once and separated from my second wife. I have two boys of my own. I spent almost two years in the Army. It’s time Judge Hardy went out and bought me a double-breasted suit. With long pants.”

Rooney wanted to stretch his wings as he had when he played Puck in Warner Brothers’ A Midsummer Night’s Dream in 1935, when The New York Times reviewed his “remarkable performance” as “one of the major delights of the work.” He wanted to enter into a new chapter of complex films like the forthcoming gritty boxing drama Killer McCoy and the Eugene O’Neill-adapted musical Summer Holiday. After the decades-long run of Hardy family movies and musicals with Judy Garland, however, Rooney’s box office draw dwindled.

Since conquering the motion picture industry with nothing but talent and grit, Rooney couldn’t have foreseen a future where he wasn’t at the top. He imagined he could reinvent his career with the same momentum he always had. As Nancy Jo Sales wrote in Vanity Fair after Rooney died in 2014, “his career suffered from his juvenile appearance, and his diminutive height — he wasn’t a boy anymore, and he wasn’t a leading man, so where did he fit in? — but he never gave up.” Rooney kept making films into the 21st century, delivering memorable performances in movies like The Black Stallion and It’s a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World. In 1979, he took on Broadway in the successful revue Sugar Babies, spawning years of tours.

Rooney’s undeniable talent steered him toward a lifelong commitment to entertainment. Given his start in the demanding realms of vaudeville and the old Hollywood studio system, the performer never hesitated to master new skills, like banjo-playing or crying on demand, to satisfy his audience. This was perhaps never more true than in 1941, when Rooney performed at President Roosevelt’s Inauguration Gala.

Alongside talents like Charlie Chaplin, Ethel Barrymore, and Irving Berlin, Rooney was expected to contribute an act of celebrity impersonations. He had a better idea: he would play his three-movement symphony Melodante on piano instead. As the Post reported, “The audience of 3,844 celebrities laughed when Rooney sat down at the piano that evening and shot his cuffs as he poised his hands over the keyboard.” They thought he was doing a bit. After he played the 19-minute score he had written himself, however, they burst into applause.

For Rooney, the label “triple threat” was an understatement. Starting from a poor broken home, he gave everything he had to build his iconic career, but it never turned out exactly the way he wanted. “People look at me and say, ‘There’s a lucky bum who got all the breaks,’” he said in 1947, “Yeah, I got the breaks — all in the neck.”

Featured image: Gene Lester, The Saturday Evening Post, December 6, 1947

Saturday Evening Post Time Capsule: July 1932

Featured image: Veteran “Bonus Army” demonstrating in Washington, D.C. (Library of Congress)