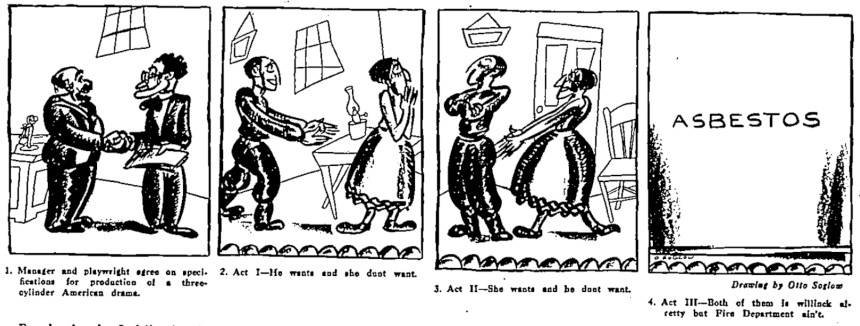

If you looked at a newspaper or magazine cartoon in, say, the 19th century, it might seem a little … off. The illustrations were packed with pen strokes, and captions were often comprised of two to four lines of wordy dialogue, resulting in the effect of a short conversation between two sketched characters.

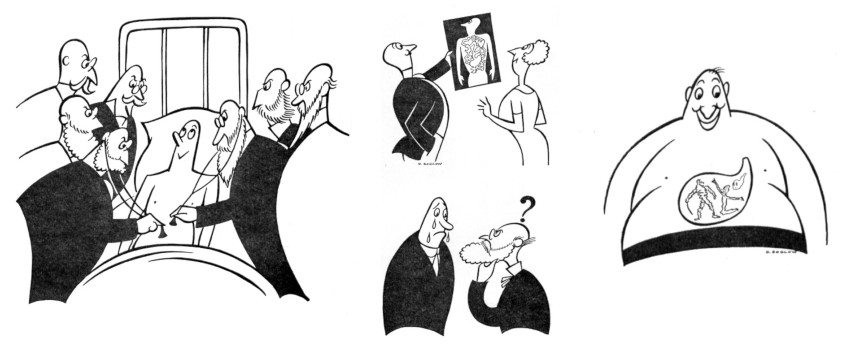

One of the cartoonists responsible for upending this style — and pioneering the kinds of strips we know today — was Otto Soglow, born on this day in 1900. At The New Yorker and, later, in this magazine and newspapers across the country, Soglow pared down lines in his illustrations, presenting a clean, minimalist rendering of whimsical characters. In the way of captions, uniquely, he often used very few or none at all, making a name for himself as a pantomime cartoonist with his popular strip The Little King, which ran for almost 40 years.

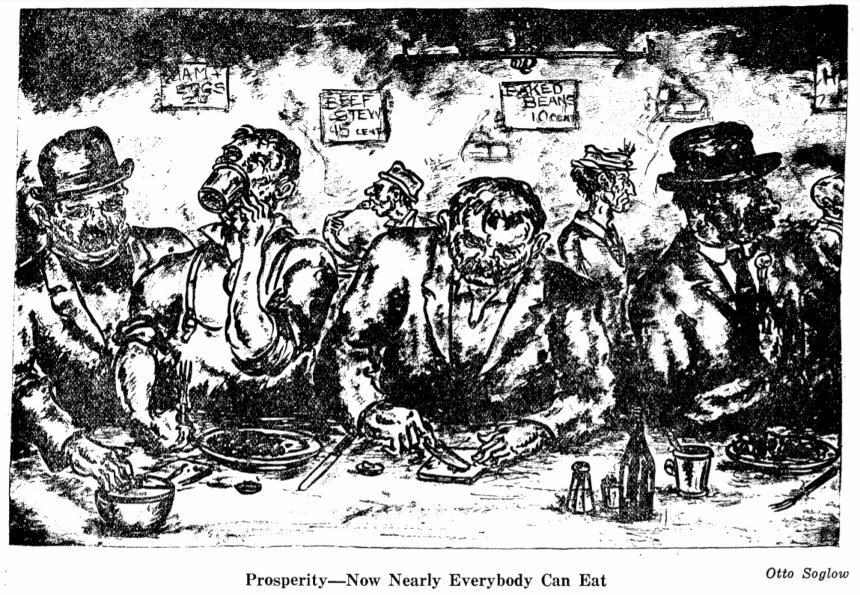

Soglow didn’t set out to become a cartoonist. A passionate performer, he dropped out of high school to pursue a career in acting. He worked as a shipping clerk, a packer, and even as a baby rattle painter before taking up illustrating professionally. In the 1920s, Soglow drew toons for the pages of radical New York publications like The New Masses and The Liberator. Influenced by the politics and aesthetics of the Art Students’ League, his work during this time depicted gritty cityscapes, working-class scenes, and socially-conscious themes.

In the August 1922 issue of The Liberator, which had published one of Soglow’s earliest illustrations the month before, the editors apologized for neglecting to credit him, saying “Soglow is to give the Liberator more of his strong work, so full of atmosphere, poetry, and sensitive observation.”

By the late ’20s, he was publishing toons and small illustrations in The New Yorker, alongside names like Peter Arno, Helen Hokinson, and James Thurber. In the magazine’s obituary for Soglow, the author noted that while his style was once busy with ink, it became purer over the years, eventually omitting all details except the most necessary: “There was nothing to distract the eye or the mind.” The New Yorker was also where Soglow introduced his most famous and enduring character: the little king.

In various weekly adventures for more than 40 years, Soglow’s “cartoon monarch” stumbled through silent, playful scenarios at the perplexity of his royal court. Far from a stereotypical depiction of a severe ruler, Soglow’s childlike king displayed no interest in power, but rather enjoyed simple pleasures like ice cream and zoo animals. While his barrel-chested guards smoked cigars, the short stubby sovereign blew bubbles out of a toy pipe. Soglow’s sight gags in his Little King strips — which were syndicated in papers around the country from 1934 to 1975 — were endearing nods to our better, more innocent, angels.

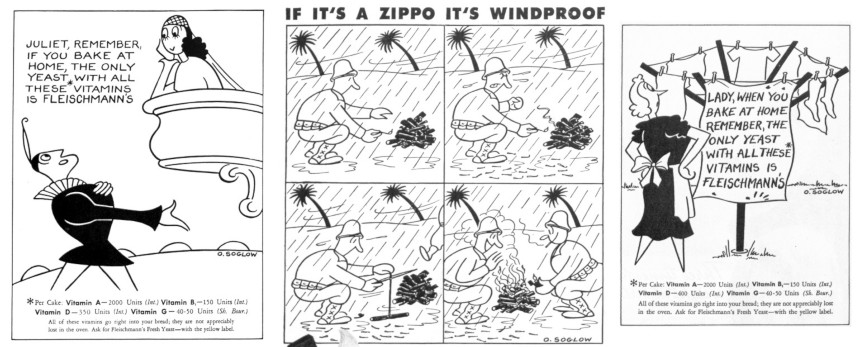

In taking his cartoons to a larger audience, the once-socialist Soglow struck a deal with newspaper magnate William Randolph Hearst. If this move wasn’t quite contradictory, his career quickly took a commercial turn as he began illustrating ads for Realsilk socks, Mutual Life Insurance Company, Fleischmann’s Yeast, Pepsi-Cola, oil companies, and others. His ads — of course, lacking the quaint charm of his other work — appeared in The Saturday Evening Post for decades. Soglow was also a staunch supporter of the war effort, designing propaganda posters and supporting art programs for soldiers.

Although he likely made a great deal of money illustrating and cartooning, Soglow never lost his desire to perform. New York newspapers in the ’30s and ’40s described him as a hit at parties, giving impersonations and magic tricks that rivalled Chaplin’s. Given his earlier penchant for the poetic and the critical, discerning audiences might be tempted to read some semblance of subtle geopolitical commentary into The Little King, but Soglow said that was baseless and “just plain silly.” As for the origin of the beloved character that graced funny pages for decades, he gave no deep, revelatory explanation; “He just happened.”

Soglow drew The Little King until he died in 1975. Although he isn’t remembered widely by the populace, the cartoonist is decidedly among the ranks of important New Yorker illustrators, and the magazine still uses his artwork in print and online. In a review of a new Little King coffee table book in 2012, Jeet Heer called Soglow “one of the central cartoonists of mid-century America.” Flipping through the comics of any paper in the country before and after Soglow, it would be difficult to disagree.

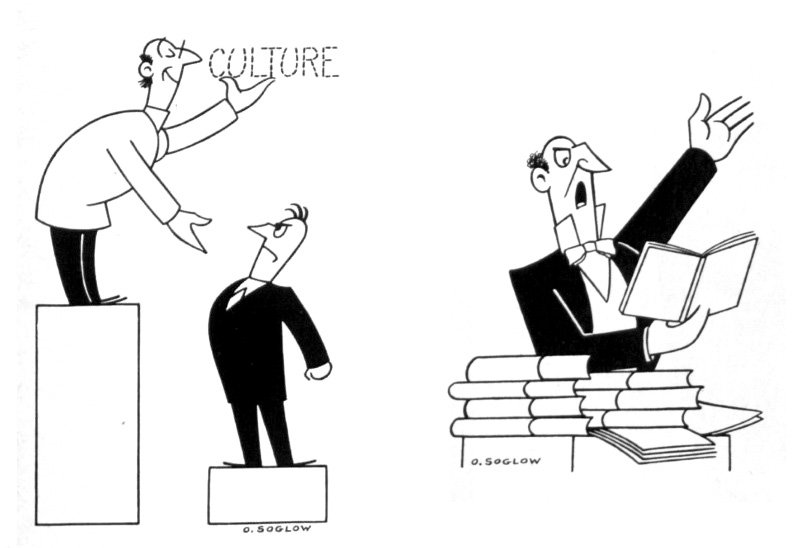

“Who Says I’m Uncultured?”/ “Let’s Keep the Filibuster,”The Saturday Evening Post, June 16, 1962, July 14, 1962

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

Gene, that’s Gluyas Williams (1888-1982) who did the fine Benchley illustrations, and so much more! And thanks to the SEP for this article about Soglow! When I was in Jnr. High and High School in the 70s, I read books about cartooning and comic strips and knew of” The Little King.” On a summer vacation in the 70s I picked up a local paper and lo and behold there was an new “Little King” strip on the comics page! I’ve seen a few recent reprints; the strip has lost none of its sweet, simple charm!

My late father, Foxo Reardon, was the creator of the original pantomime comic strip, “Bozo”which he created at age 16 when working as a cartoonist for the Richmond Times-Dispatch in 1921. The strip appeared in that paper regularly from the early 1920s and was internationally syndicated by the Chicago Sun-Times in 1945. It appeared all over the world until my father’s untimely death from cancer in 1955. The Syndicate promoted it as the original pantomime comic strip, a fact never disputed.

I enjoyed “The Little King”, but didn’t Soglow also illustrate the Robert Benchley books?

Very nice of you to remember/honor Mr. Soglow on his 120th anniversary. I wasn’t familiar with his name, but some of his works, yes. This would include those cartoon Pepsi ads from the 40’s. I have some LIFE magazines from World War II (I got in the late 90’s) and saw them there. Not surprised they were in the Post too, with both often carrying the same ads.