Eugene Field Helped Craft America’s Sense of Humor, Then We Forgot Him

When Eugene Field died in 1895 at age 45, fellow authors and friends hastened to share their fond memories of the humorist and poet. He was a hilarious prankster and a heavy drinker with an impressive book collection, but, most of all, he was a loyal friend.

Field was born 170 years ago on September 2, 1850, although he reportedly told people his birthday was September 3rd if they were late to wish him a happy birthday, just so they wouldn’t feel too bad about it.

Even though more than 30 elementary schools around the country have been named after the prolific writer, his literary renown has scarcely held up to the household-name status he enjoyed during his life. As a poet, he crafted the most popular children’s poems and lullabies of the era, including “Little Boy Blue,” “Wynken, Blynken, and Nod,” and “The Sugar-Plum Tree,” all of which were published in this magazine or its affiliated children’s magazines. As a newspaperman, Field garnered a national following for his witty columns documenting people and the arts, first in Missouri, then in Denver, and finally at the Chicago Daily News.

His column “Sharps and Flats” ran in the latter paper six days a week for the last 12 years of his life. By at least one account, he was the most popular columnist in the country during that time. Of a young Rudyard Kipling, Field wrote that “he has been flattered to an amazing degree since he woke up one morning and found himself famous” and that “there may be … twenty newspaper reporters in New York City capable of doing as good work as Mr. Kipling has done; at the same time, they have not done it and Mr. Kipling has.” Field gushed over a World’s Fair exhibit on Hans Christian Andersen, writing of “that dear heart which beat in unison with the simplicity, the truth, the candor, the enthusiasm, the wisdom, and the pathos of childhood!”

Field was also known for his scathing and sardonic quips on politicians of the day. In 1883, he wrote, “Grover Cleveland seems to have suddenly and completely dropped out of sight. Perhaps he is rehearsing Santa Claus for a Sunday-school celebration next Christmas. These politicians are queer people.” Writing for the Denver Tribune, he offered whimsical advice for all children aspiring to go into politics: “If you neglect your education and learn to chew plug tobacco, maybe you will be a statesman some time. Some statesmen go to Congress and some go to jail. But it is the same thing, after all.” One can imagine that Field would have found no shortage of bon mots to pen on the Progressive Era of American politics, had he lived to see it.

A few years after his death, Francis Wilson memorialized the writer in a biography published in this magazine as “The Eugene Field I Knew,” writing, “Field’s mind and heart were wide open to the sunshine of humor and the joy of laughter.” Sometimes this candidness expressed itself in wild antics, as when Field reportedly pranked a posh Thanksgiving dinner party by exploding the turkey with a firecracker: “He wasn’t invited back.”

Field’s close friend George H. Yenowine wrote for the Post several years later on “The Serious Side of Eugene Field,” claiming he had received the former’s last written letter. Yenowine noted that Field wrote his correspondence in six different colors of ink, depending on the tone of a given letter. He was also known to spend hours embellishing the margins with drawings and designs. In his letter to Yenowine two days before his death, Field went on excitedly about many projects he was looking forward to, before finishing the missive with a characteristic confession: “Irving Way has been wanting me to do the preface to the volume of Anne Bradstreet’s poems which the Duodecimo will publish; but Anne is a tough, uncongenial old bird, and I hesitate to tackle her. I suppose that one is justified in putting off a task he feels he cannot do well.”

Although Field’s prominence in the American literary canon has waned, his influential effect on humorists into the 20th century, such as John T. McCutcheon, Mark Twain, and even — tangentially — Molly Ivins, is undeniable. Don Marquis professed that he read “Sharps and Flats” every day. In his 2001 biography, Eugene Field and His Age, author Lewis O. Saum claims that Field created the newspaper column, and yet much of the writer’s work from the Chicago Daily News was lost forever: “We knew him very well for something like a half-century. Then, recalling little other than something labeled ‘calamitously sentimental,’ we averted our gaze.”

Field’s irreverent approach to constructing the record of the day can be remembered as a quaint, but formative, addition to the uniquely American voice; the oversized role he played in holding a mirror to the country and its politics at such a precarious time as the late 19th century has received a fraction of the attention it deserves.

Featured image: Buffalo Evening News, December 3, 1895

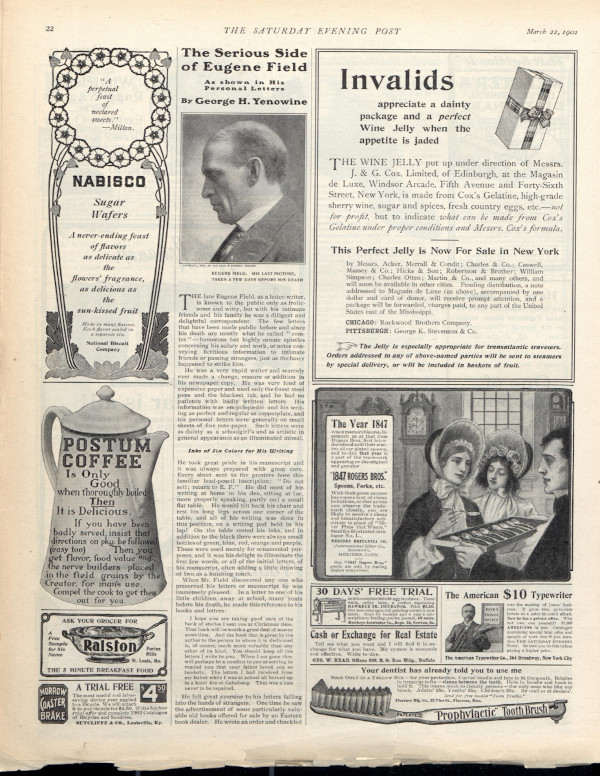

An Interview with Margaret Guroff on How Bicycles Built Our Highways

Margaret Guroff is the author of The Mechanical Horse: How the Bicycle Reshaped American Life (2016), from which her essay “How Bikes Built Our Highways” is adapted.

Margaret Guroff is the author of The Mechanical Horse: How the Bicycle Reshaped American Life (2016), from which her essay “How Bikes Built Our Highways” is adapted.

Ramona Whittaker: How did you become interested in bicycles and their impact on America’s highways?

Margaret Guroff: I saw a brief mention in a history book about how cyclists were instrumental in getting U.S. roads paved in the 1890s. Until then, I hadn’t really been aware of bikes as existing before cars, and when I started to look into the role of the bicycle in American culture, I found its influence all over—not only in the Good Roads Movement, but in the auto industry, the invention of the airplane, the development of consumer culture. The bicycle also influenced the way women dressed and it empowered women during 1890s when they were getting together to advocate for the vote.

RW: The mode of transportation became a game changer?

MG: Exactly. On bicycles, young women could get around without chaperones — which had been frowned upon before — and they could get where they were going under their own steam. Bicycling also helped people understand that exercise was good for you — something many Americans didn’t believe before the bicycle. They thought that if you did something that made your heart rate rise, you would damage your heart. A lot of people really didn’t know that if you exercise, it makes you feel stronger. And many doctors thought that you were born with a certain amount of energy. When you spent it, that was it. Doctors were very likely — particularly as adults got older — to say, “You just have to sit down, just chill.”

RW: Was that true especially for women?

MG: Yes. Proper women wore corsets to help them carry all their clothing — which could add up to 25 pounds of skirts, dresses, and stuff. A corset helped distribute this weight up and down their torsos. But all that weight and the constriction of a corset made it likely that if they stood up or moved too fast, they would faint. This created an illusion that women were weak and shouldn’t exert themselves.

RW: How did the bicycle change women’s fashion, and how did the public react?

MG: Dress reforms were actually proposed in the middle of the 19th century. Women’s rights advocates Amelia Bloomer, Susan B. Anthony, and Elizabeth Cady Stanton all decided to wear Turkish-style flowing pants that were weren’t constraining or heavy but were still very modest. They thought it was a much healthier way for women to dress, and they were trying to set a trend. They eventually had to give it up, because they were being harassed. Critics called the outfit a “bloomer costume.” They’d yell at these women and even throw things at them. So, bloomers didn’t catch on in the 1850s. But when the bicycle became popular at the end of the 19th century, women realized they couldn’t ride in their long, flowing skirts, and some of them started wearing the bloomers that had been advocated 40 years earlier. These women also were mocked. It’s not like it was normal for women to wear pants in 1890. A story on the front page of a tabloid called the National Police Gazette in 1893 carried the headline “She Wore Trousers” as if it was shocking that a woman would do this in public. The difference was that even though women wearing bloomers in the 1890s were getting the same kind of harassment as Amelia Bloomer did in the 1850s, they had a new motivation. They were willing to put up with mockery to be able to ride bicycles. Within just a few years, there were so many women riding bicycles that it became much more acceptable to wear pants or shorter skirts to do so.

RW: Did bicycles offer women a new form of independence and sense of freedom?

MG: Yes, it’s amazing. In 1896, Susan B. Anthony said, “Let me tell you what I think of bicycling. I think it has done more to emancipate women than anything else in the world. It gives women a feeling of freedom and self-reliance. I stand and rejoice every time I see a woman ride by on a wheel…the picture of free, untrammeled womanhood.” She saw clearly that the bicycle was motivating non-activists to take political action. They thought they were just having fun, but really were turning the culture upside down.

MG: Yes, it’s amazing. In 1896, Susan B. Anthony said, “Let me tell you what I think of bicycling. I think it has done more to emancipate women than anything else in the world. It gives women a feeling of freedom and self-reliance. I stand and rejoice every time I see a woman ride by on a wheel…the picture of free, untrammeled womanhood.” She saw clearly that the bicycle was motivating non-activists to take political action. They thought they were just having fun, but really were turning the culture upside down.

RW: What was one of the most surprising things you learned about the bicycle in your research?

MG: One of the coolest things I learned was about the Wright brothers. Everyone knows they were bicycle mechanics, but it always seemed to me a coincidence that bicycle mechanics invented the airplane. What I discovered by reading the work of historians like Tom Crouch, who wrote a great biography of the Wright brothers called The Bishop’s Boys, was that the bicycle gave the Wrights a crucial insight into how to keep an airplane aloft. Many inventors who were working on airplanes were trying to throw something in the air that would know how to go straight on its own. The Wright brothers went at it a different way. They realized that you don’t have to create a machine that knows on its own to go straight, because the pilots can be the brains of the machine. When you’re riding a bike, your body becomes one with the machine, and your sense of balance, and the unconscious corrections you make as you ride, are what balance the machine. The Wrights were able to take that same concept and put it in the air.

RW: Can you tell us more about the history of biking in America versus that of biking in Europe? Did bicycling affect other countries the same way it affected ours?

MG: Though a lot of developments were parallel, there were some interesting divergences. The main one came at the end of the 19th century. There had been a big 1890s bike boom in Europe as well as the U.S., but when that fad ended in the U.S., bike use really dropped off a cliff here. People without horses still rode them get to work or make deliveries, but they became absolutely unfashionable. Nobody rode them for fun. And this is years before the automobile became affordable for anyone other than the super rich. In order to keep the market for American bicycles going, bicycle manufacturers started targeting the youth market. They ended up making bicycles a childhood necessity, but they also made bikes seem like they were only for kids. As soon as you turned 16, you wouldn’t be caught dead on one, and no adult would ride one. That was very much an American phenomenon; it didn’t happen anywhere else as far as I’m aware, and it didn’t really start to turn around until the 1960s. There was a huge bike boom here in the 1970s, and by the 1980s, the United States started exporting styles, like the rugged mountain bike with straight handlebars that you could ride off-road. That was invented in the United States and caught on overseas.

RW: Would you say that biking in the U.S. today is as common as it is in Europe?

MG: It’s not, but in American cities, it can feel like it’s going in that direction. There are many more bike lanes than there were 10 years ago. There are many more people on bikes, including middle-aged people and young parents toting kids around. Where it’s safe to ride and people live near places they need to go, there is a mini-boom, though nationally, bike ridership is going down. Outside of the prosperous parts of cities, many people don’t live near their work, church, or shops, so bicycling is not practical for them. And in many parts of the country, roads are designed to allow cars to go as fast as possible, which makes them too dangerous for cyclists. And it’s no longer the case that every American kid has a bike, because a lot of kids don’t have a safe place to ride or don’t live close enough to the places they’d want to ride to.

RW: Are many people concerned about climate change biking to and from work?

MG: Riding your bike more is certainly one way you can reduce your carbon footprint. But it has to be practical for people. You have to get to work, you have to haul groceries, you have to get your kids to school. If you live in a place where it’s not possible to do those things on a bike or on foot or with public transit, you’re going to have to drive. Cities have a vested interest in making it easier for people to bicycle because bikes don’t pollute the air, they don’t cause wear and tear on the roads, they don’t create the same parking demands.

RW: Bikes are very popular on college campuses.

MG: Colleges are typically places where everything is closer together, so they’re easy to get around by bike. And most students who live on campus don’t have little kids that they need to provide transportation for, or jobs many miles away that they have to commute to. So bikes work well in that environment.

RW: If bicycles became a more popular form of transportation, where would they have the most impact? What would be the effect of more bicycles on the road?

MG: That’s hard to say, because there are changes coming to traffic that could make the roads much safer for bikes and pedestrians, or much less safe. We know that we’re going to have autonomous cars soon. But how are they going to behave? Will they be well programmed and well-regulated to make traffic calmer and more logical, and make it safer for bikes? Or will they be out there like bumper cars, clipping anything that gets in their way? If the roads do become safer for bikes, you’ll see more of them — studies show that the safer it is to ride, the more people ride.

MG: That’s hard to say, because there are changes coming to traffic that could make the roads much safer for bikes and pedestrians, or much less safe. We know that we’re going to have autonomous cars soon. But how are they going to behave? Will they be well programmed and well-regulated to make traffic calmer and more logical, and make it safer for bikes? Or will they be out there like bumper cars, clipping anything that gets in their way? If the roads do become safer for bikes, you’ll see more of them — studies show that the safer it is to ride, the more people ride.

RW: What are the most bike-friendly cities in the U.S.?

MG: Brooklyn is one of the centers of biking in the country. Also Portland, Oregon, is huge for biking. Seattle is really good for biking. I work in D.C., which has one of the highest bike-commuting rates in the country. We have laws that are very helpful, such a leading pedestrian indicator law that gives pedestrians and bikes a few extra seconds to cross the street, so that they clear the intersection before traffic starts moving. It makes everybody safer and makes traffic move better. Chicago is supposed to be great and also Minneapolis, which is amazing to me because it’s so cold up there. But you can bike all winter long, you just have to have the right gear.

One really exciting thing that’s happening all over the country is the rise of bike-share systems. You use your credit card to check out a bike, go where you’re going, and check it back in. That’s an amenity that can make biking accessible to people who can’t necessarily use a bike as their main form of transportation. In New York, for example, if you live in one of the outer boroughs, you can take the subway into Manhattan for work, but then use a bikeshare bike to go across town for lunch or something. Bikeshares are turning American cities into places where you can bike on a whim, where you might not have wanted to or been able to before.

RW: Do you ride your bike to work, and what kind of bicycle do you own?

MG: Yes, I ride a green 1999 Jamis Aurora touring bike. I love it. I ride an hour to work — it’s about half an hour on a woodsy rails-to-trails path — and then across town through traffic. By the time I get to my desk, I feel like a hero.

Read Margaret Guroff’s essay, “How Bikes Built Our Highways,” which appears in the January/February 2016 issue of The Saturday Evening Post.

Ads You’ll Never See Again: 19th Century Snake Oil

Prior to the Pure Food and Drug Act of 1906, entrepreneurs could make any claim they wanted for their special medicines, herb tonics, electric belts, and hair restorers. Not only did these remedies usually not work, they sometimes caused more harm than good.

Many of these elixirs, remedies, and “vegetable restoratives” were heavily laced with alcohol, codeine, or opium. While the ads for patent medicines made all sort of promises, none was more fantastic than the promise of “satisfaction guaranteed.”

The makers of patent medicine might have actually believed in their product’s ability to cure, but they definitely believed in the power of advertising. Periodicals of the 19th century were filled with ads for patent medicines. The Post and of the 19th century seems to have avoided some of the more outrageous patent-medicine ads. Even so, we’ve found a few interesting examples.

The Saturday Evening Post

February 15, 1873

Medical marijuana: A doctor cures his only child of tuberculosis with cannabis.

The Saturday Evening Post

July 6, 1878

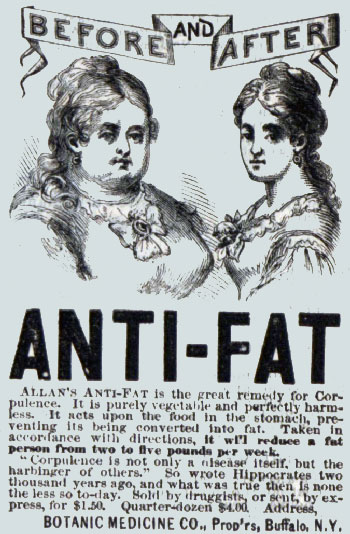

How many people jumped at the chance to lose “from two to five pounds per week”?

The Saturday Evening Post

October 4, 1879

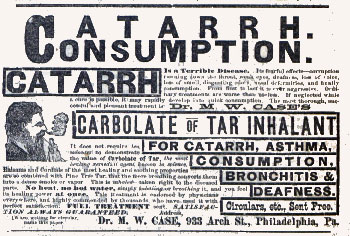

Dr. Case warned that catarrh (a buildup of phlegm or mucus) could lead to tuberculosis (then the leading cause of death in America) but could be remedied by breathing fumes of wood tar.

The Country Gentleman

September 11, 1879

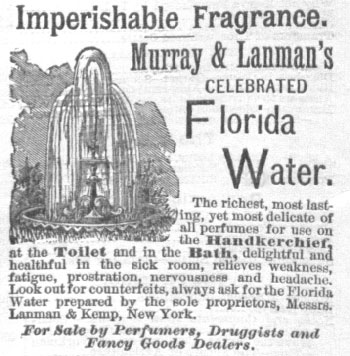

Florida Water was a cologne using orange scent. The fountain in the ad refers to the Fountain of Youth, which Ponce de Leon presumably found in Florida. Florida Water is still being sold (lanman-and-kemp.com) but without claims of health benefits.

The Country Gentleman

March 25, 1880

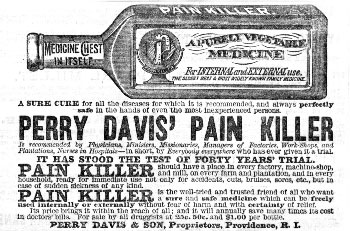

Today, we might wonder how a painkiller could be “always perfectly safe in the hands of even the most inexperienced persons.”

The Saturday Evening Post

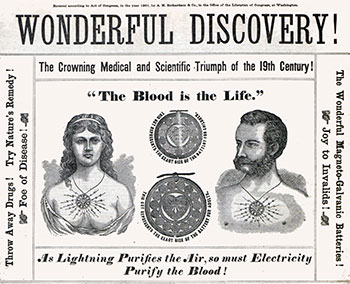

January 29, 1881

This illustration appeared above a full-page ad for A.M. Richardson’s Wonderful Magneto-Galvanic Battery, which was claimed to revitalize and strengthen organs—without actually specifying which ones. The company recommended it for 56 different ailments, including meningitis, diabetes, heartburn, and “hysteria or fits.”

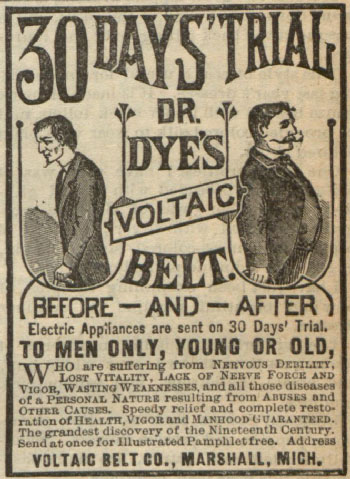

The Saturday Evening Post

January 30, 1883

“Speedy relief and complete restoration of Health, Vigor and Manhood guaranteed.” How could anyone not be satisfied with a promise like that?

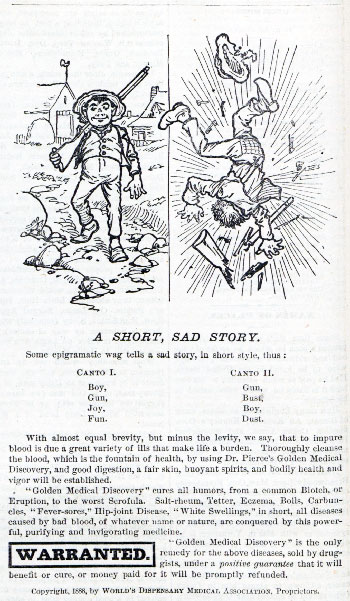

The Saturday Evening Post

January 13, 2016

It’s only after you’ve read most of the ad for “Golden Medical Discovery” that you realize the grisly cartoon has nothing to do with the product.

Coming Soon from The Saturday Evening Post: Ads You’ll Never See Again

A special collector’s edition of The Saturday Evening Post filled with ads from the past that will delight, entertain — and sometimes shock — with images and concepts that are thoroughly inappropriate today. You’ll cringe when you see babies wrapped in then-brand-new cellophane. You’ll laugh out loud at Santa promoting a cigarette brand. You’ll wince at an ad that threatens housewives with a spanking for failing to complete their domestic chores. More than just an entertainment, the special issue offers a snapshot of attitudes about gender, childrearing, and marketing in an era that most readers will remember all too well.

It’s too early to order, but if you might be interested in purchasing this product, please click here and we’ll send you a notice when the special issue is available.