When Eugene Field died in 1895 at age 45, fellow authors and friends hastened to share their fond memories of the humorist and poet. He was a hilarious prankster and a heavy drinker with an impressive book collection, but, most of all, he was a loyal friend.

Field was born 170 years ago on September 2, 1850, although he reportedly told people his birthday was September 3rd if they were late to wish him a happy birthday, just so they wouldn’t feel too bad about it.

Even though more than 30 elementary schools around the country have been named after the prolific writer, his literary renown has scarcely held up to the household-name status he enjoyed during his life. As a poet, he crafted the most popular children’s poems and lullabies of the era, including “Little Boy Blue,” “Wynken, Blynken, and Nod,” and “The Sugar-Plum Tree,” all of which were published in this magazine or its affiliated children’s magazines. As a newspaperman, Field garnered a national following for his witty columns documenting people and the arts, first in Missouri, then in Denver, and finally at the Chicago Daily News.

His column “Sharps and Flats” ran in the latter paper six days a week for the last 12 years of his life. By at least one account, he was the most popular columnist in the country during that time. Of a young Rudyard Kipling, Field wrote that “he has been flattered to an amazing degree since he woke up one morning and found himself famous” and that “there may be … twenty newspaper reporters in New York City capable of doing as good work as Mr. Kipling has done; at the same time, they have not done it and Mr. Kipling has.” Field gushed over a World’s Fair exhibit on Hans Christian Andersen, writing of “that dear heart which beat in unison with the simplicity, the truth, the candor, the enthusiasm, the wisdom, and the pathos of childhood!”

Field was also known for his scathing and sardonic quips on politicians of the day. In 1883, he wrote, “Grover Cleveland seems to have suddenly and completely dropped out of sight. Perhaps he is rehearsing Santa Claus for a Sunday-school celebration next Christmas. These politicians are queer people.” Writing for the Denver Tribune, he offered whimsical advice for all children aspiring to go into politics: “If you neglect your education and learn to chew plug tobacco, maybe you will be a statesman some time. Some statesmen go to Congress and some go to jail. But it is the same thing, after all.” One can imagine that Field would have found no shortage of bon mots to pen on the Progressive Era of American politics, had he lived to see it.

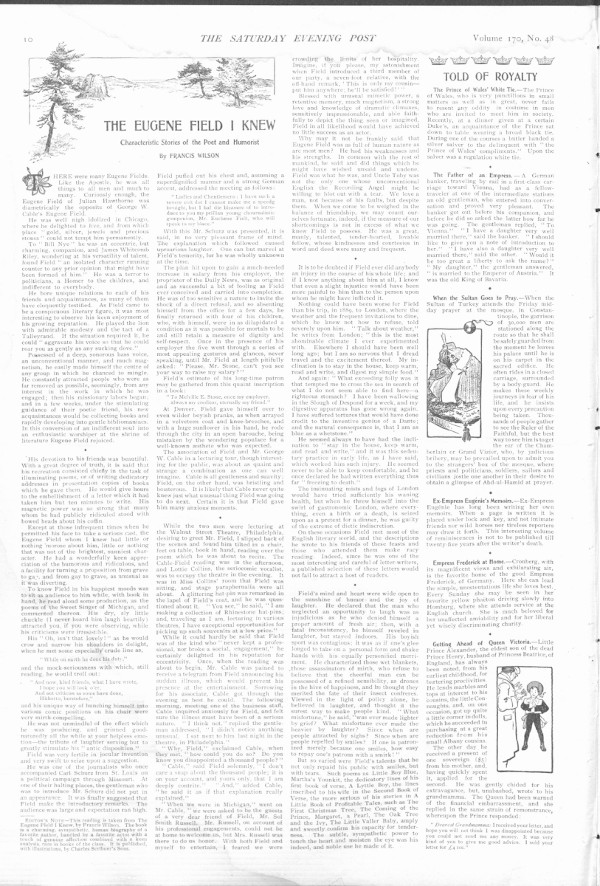

A few years after his death, Francis Wilson memorialized the writer in a biography published in this magazine as “The Eugene Field I Knew,” writing, “Field’s mind and heart were wide open to the sunshine of humor and the joy of laughter.” Sometimes this candidness expressed itself in wild antics, as when Field reportedly pranked a posh Thanksgiving dinner party by exploding the turkey with a firecracker: “He wasn’t invited back.”

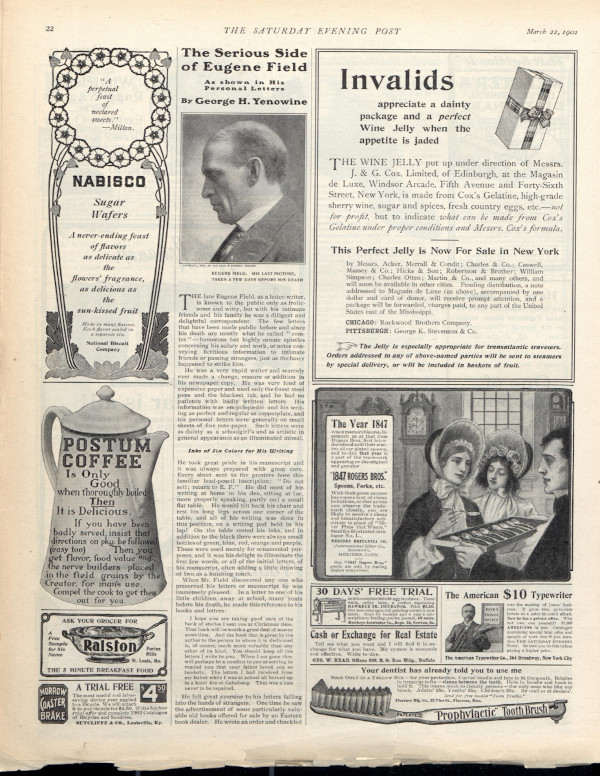

Field’s close friend George H. Yenowine wrote for the Post several years later on “The Serious Side of Eugene Field,” claiming he had received the former’s last written letter. Yenowine noted that Field wrote his correspondence in six different colors of ink, depending on the tone of a given letter. He was also known to spend hours embellishing the margins with drawings and designs. In his letter to Yenowine two days before his death, Field went on excitedly about many projects he was looking forward to, before finishing the missive with a characteristic confession: “Irving Way has been wanting me to do the preface to the volume of Anne Bradstreet’s poems which the Duodecimo will publish; but Anne is a tough, uncongenial old bird, and I hesitate to tackle her. I suppose that one is justified in putting off a task he feels he cannot do well.”

Although Field’s prominence in the American literary canon has waned, his influential effect on humorists into the 20th century, such as John T. McCutcheon, Mark Twain, and even — tangentially — Molly Ivins, is undeniable. Don Marquis professed that he read “Sharps and Flats” every day. In his 2001 biography, Eugene Field and His Age, author Lewis O. Saum claims that Field created the newspaper column, and yet much of the writer’s work from the Chicago Daily News was lost forever: “We knew him very well for something like a half-century. Then, recalling little other than something labeled ‘calamitously sentimental,’ we averted our gaze.”

Field’s irreverent approach to constructing the record of the day can be remembered as a quaint, but formative, addition to the uniquely American voice; the oversized role he played in holding a mirror to the country and its politics at such a precarious time as the late 19th century has received a fraction of the attention it deserves.

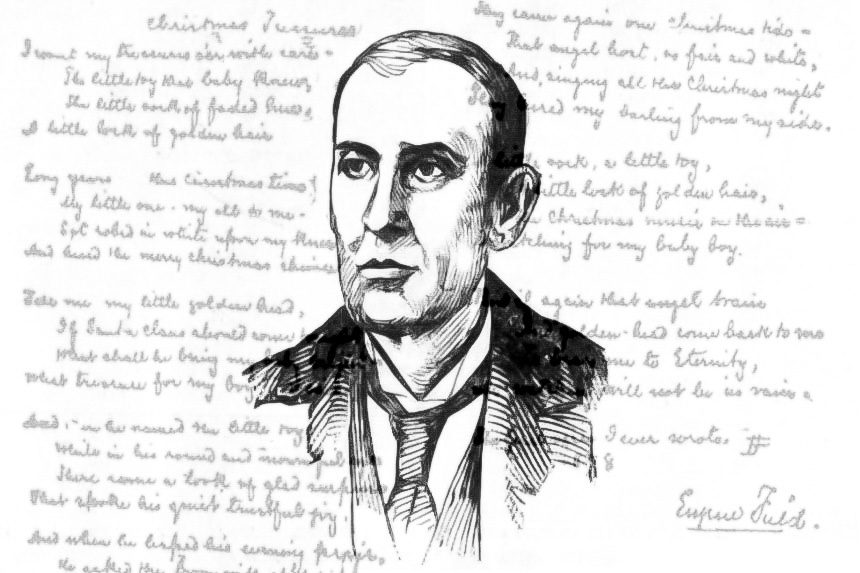

Featured image: Buffalo Evening News, December 3, 1895

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now