The Art of the Post: How Magazines Revolutionized the Art World

We are pleased to introduce the first of a biweekly column on art and illustration by art critic and historian David Apatoff. David will share exciting and interesting illustrations, reveal colorful stories about Post artists and their methods, and offer insights into why art and illustration are such an important part of our culture. We hope you enjoy it!

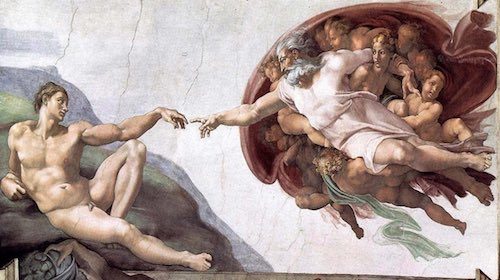

For 10,000 years, artists were hired by the wealthy and powerful. Kings, priests, pharaohs, and popes commissioned art for cathedrals, palace walls, sacred caves, and public spaces.

Then, gradually, this market for art faded away. Kings began to vanish from the Earth; churches stopped commissioning altar paintings and chapel ceilings; princes no longer hired artists for flattering portraits or murals of glorious military victories. Their castles were handed over to public trusts in exchange for tax deductions.

Artists had to find new places to sell their art.

Fortunately, a new breed of sponsor arose to replace those historical patrons of the arts. The growth of capitalism and the invention of the corporation gave private citizens the wealth to commission art. Businesses began purchasing “commercial art.” Even more importantly, new technologies for mass-producing pictures and distributing them to wide audiences enabled working families — whether rich or poor — to enjoy great art in their homes. Rather than compete to become a royal painter, artists could now publish millions of copies of a picture and sell them to large numbers of customers for pennies apiece.

In the 19th century, The Saturday Evening Post was one of a small handful of American magazines, along with Harper’s Weekly, Century, and Life, that were densely printed black-and-white periodicals with wood engravings for illustrations.

By the 20th century, the magazine industry had blossomed into dozens of popular and well-designed color periodicals. Historians have dubbed this the “magazine revolution.” The quality of reproductions, and the newly sophisticated vehicles for delivering them to the public, transformed the economics of art and inspired new bursts of creativity. Public enthusiasm for new pictures grew dramatically as technology for reproducing pictures in magazines improved.

The Post soon became the most widely circulated magazine in America. This was largely due to editor George Lorimer’s vision of taking advantage of the newly available technologies for printing images.

The most talented artists learned they could become wealthy by creating pictures for the new mass audiences. Illustrators such as Norman Rockwell, Maxfield Parrish, J.C. Leyendecker, and Charles Dana Gibson received handsome sums illustrating magazines. Their covers became a popular topic of conversation across the country. The art inside the magazines — ranging from story illustrations to imaginative advertisement pictures — shaped popular taste, too.

Several of the images created by these illustrators became cultural icons. In this way, the modern magazine became one of the world’s greatest platforms for art.

Great painters of the era aspired to be magazine illustrators. In letters to his brother, Vincent van Gogh praised the quality of illustrations in magazines such as Harper’s Weekly and Illustrated London News, and he clipped out their drawings and pasted them in portfolios for further study. The great abstract expressionist Willem de Kooning came to America to become a commercial artist.

As the technologies continued to evolve, the next generation of illustrators was able to make images that moved and spoke. At animation studios such as Disney and Pixar, they painted with computers rather than brushes. Today, illustrators are pioneers in computer games employing virtual reality. But no matter how advanced the technologies become, illustrators continue to look back and gain inspiration from their artistic roots in magazine illustration.

With all these changes in the landscape of art, it’s fair to ask: Who was the greatest art patron of the 20th century? If we measure by the size of the audience and the influence of the art, one good candidate is The Saturday Evening Post.

The Post’s circulation in the first half of the 20th century was far greater than the audience enjoyed by any museum or private collection of the period. Every week, the Post delivered a cornucopia of pictures, not just to audiences in big cities but to people in small towns with no museums, libraries, or televisions. Many of its illustrators recognized this fact and took their artistic obligations seriously. Post illustrator Robert Fawcett said, “We represent the only view of art and beauty that millions of people get a chance to see. If we do less than our best, we cheat them.”

For many years, the weekly audience for the Post was larger than the audience for Picasso, Matisse, or any other giants of 20th century modern art. Furthermore, the art in the Post’s illustrations had more of an impact on day-to-day lives, shaping cultural identity and political beliefs in ways that museum artists never did. They drove consumer choices, sold war bonds, persuaded young men to join the army (“Uncle Sam Wants You!”), and affected our standards of beauty, patriotism, love, and ethics. And as Lionello Venturi, the foremost historian of art criticism, has pointed out, “What ultimately matters in art is not the canvas, the hue of oil or tempera, the anatomical structure and all the other measurable items, but its contribution to our life, its suggestions to our sensations, feeling and imagination.”

Several fine art critics of the 20th century have argued that in order to be accessible to a wider audience, illustrators sacrificed avant garde art principles, making illustration a lesser art form. But the passage of time has caused experts to re-examine that view. Today, illustration is increasingly respected by museums, academics, and collectors. Meanwhile, so-called “fine” art is viewed by many as esoteric, self-absorbed, and irrelevant. Noted writer and art critic Tom Wolfe said in a speech at the National Museum of American Illustration, “I feel very comfortable predicting that art historians 50 years from now … will look back upon illustrators as the great American artists of the second half of the 20th century.”

As Shakespeare proved, broad appeal to a popular audience is not incompatible with greatness.

A wealth of 20th-century illustration lies behind us, largely unexamined and underappreciated. It is one of my great pleasures to help unearth that art and consider its qualities afresh, on a level playing field with other art forms. I hope you will join me here for an interesting ride.

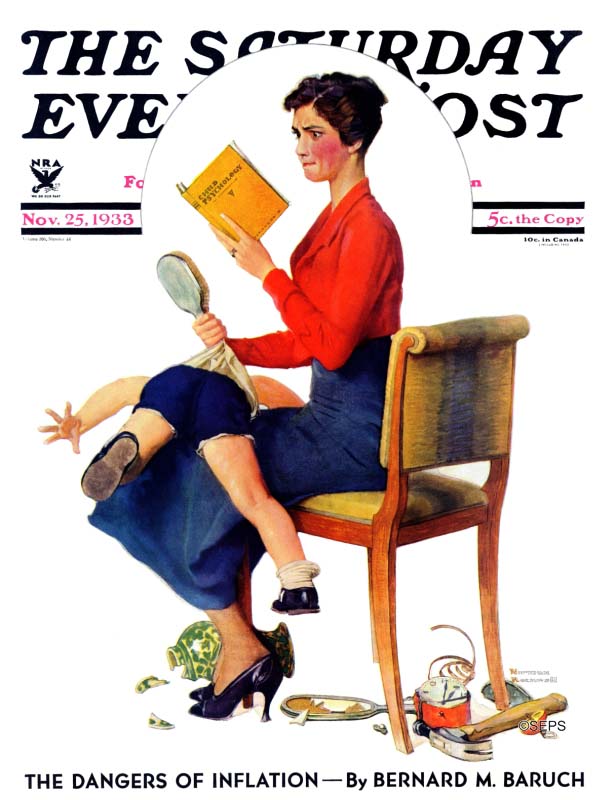

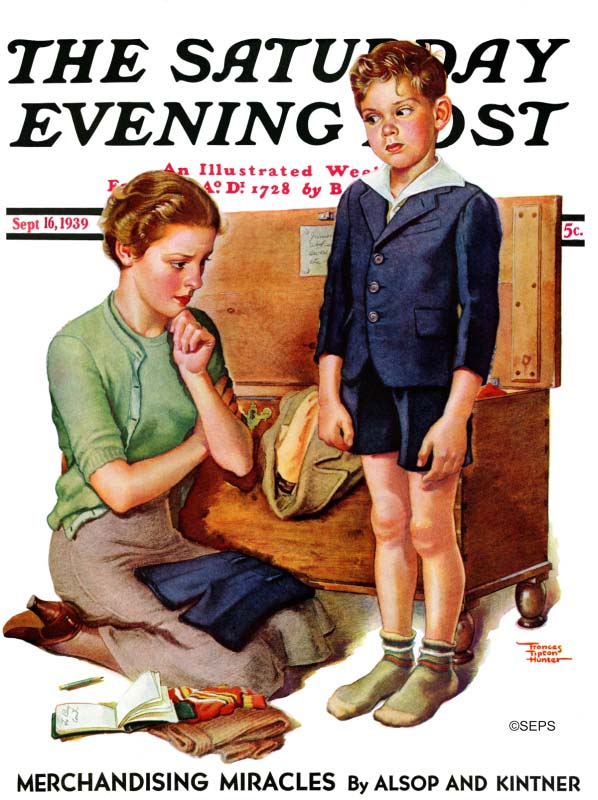

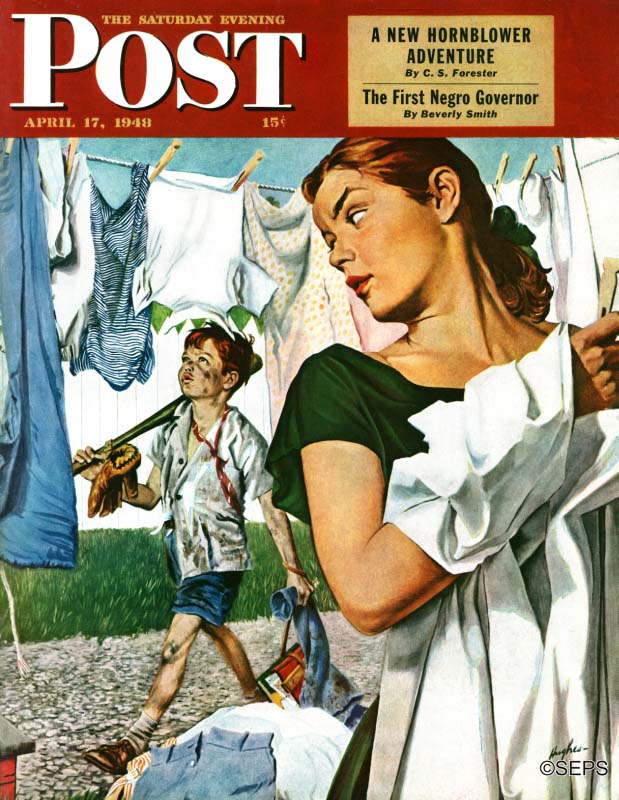

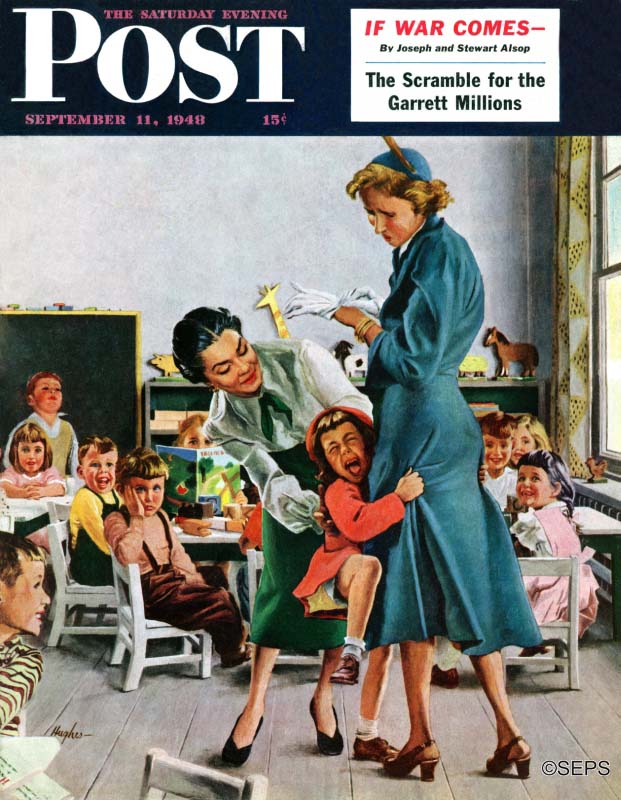

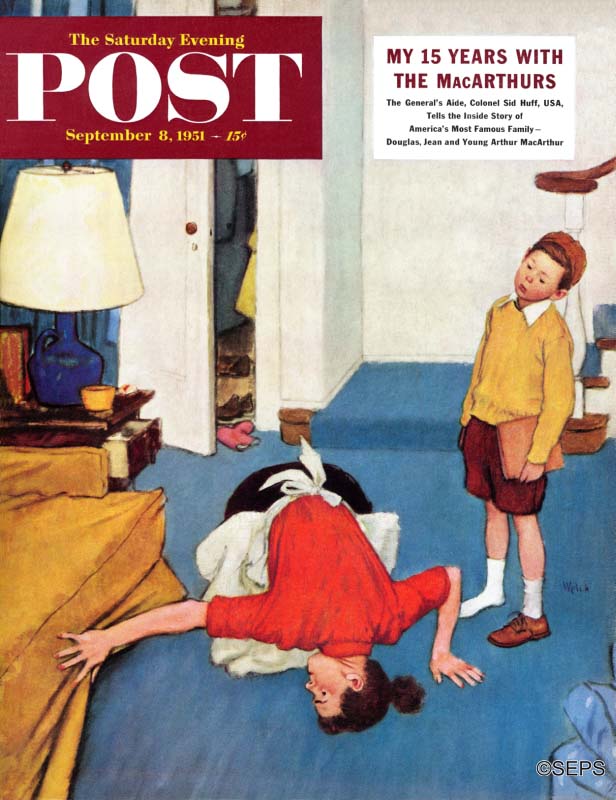

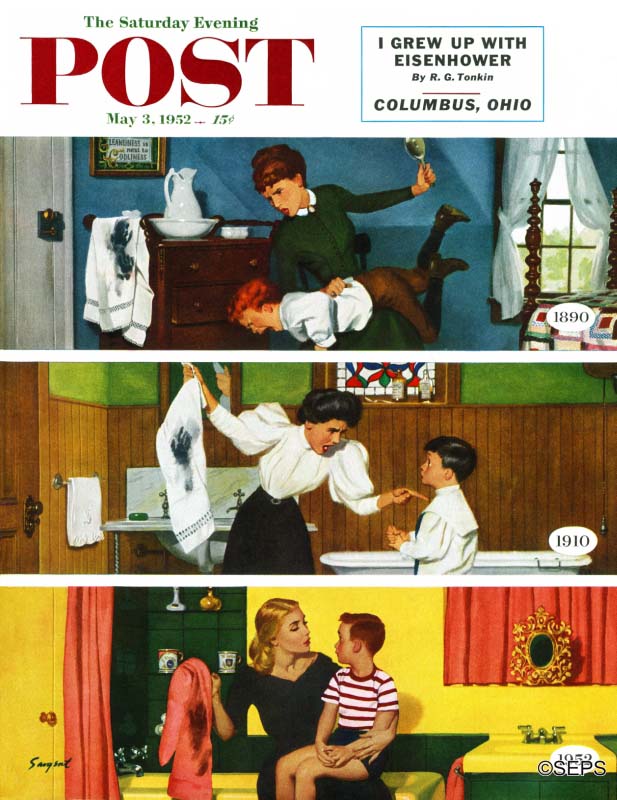

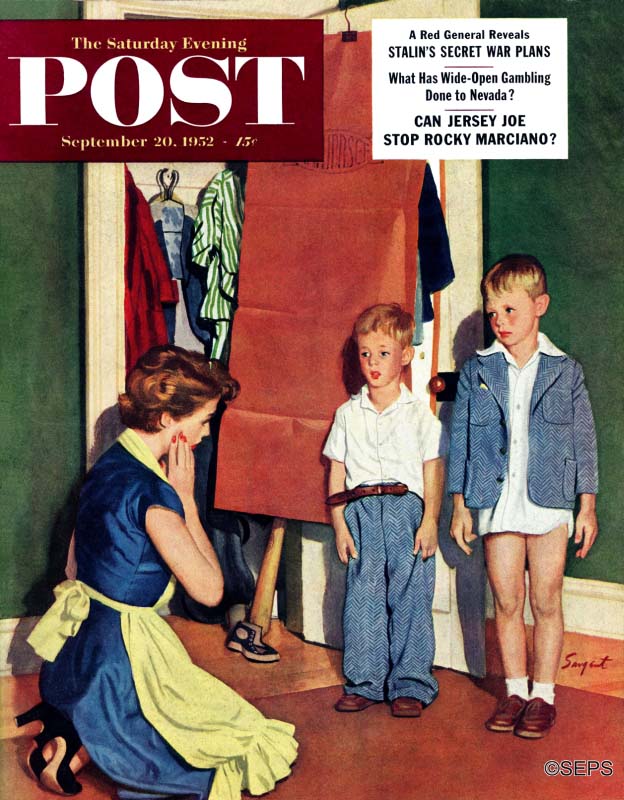

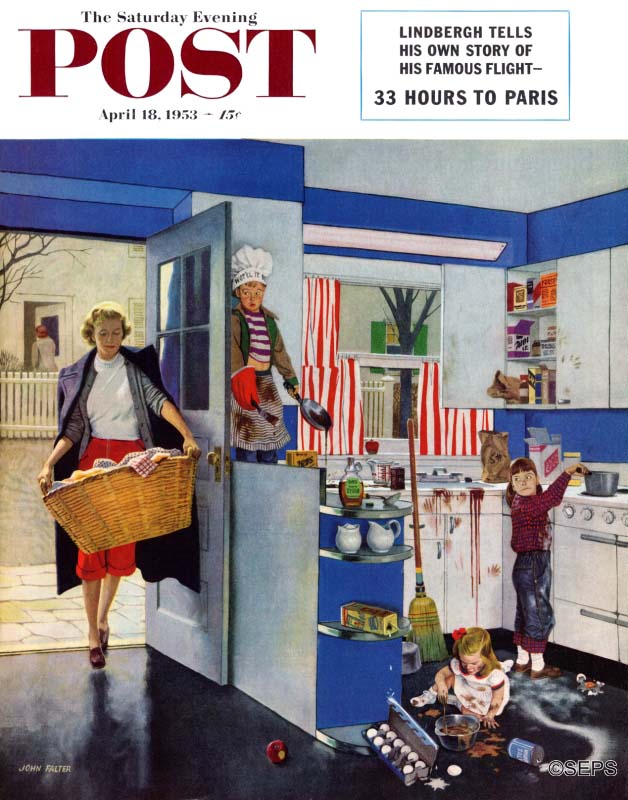

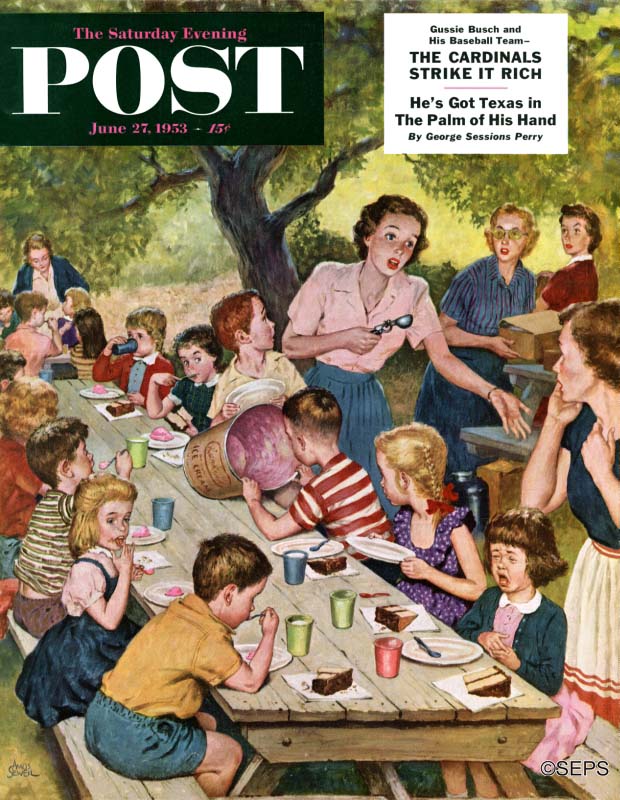

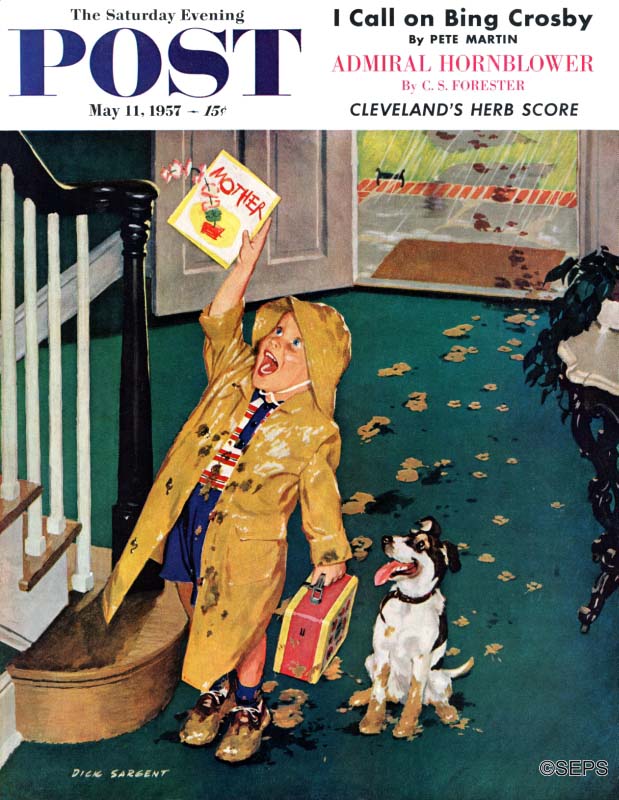

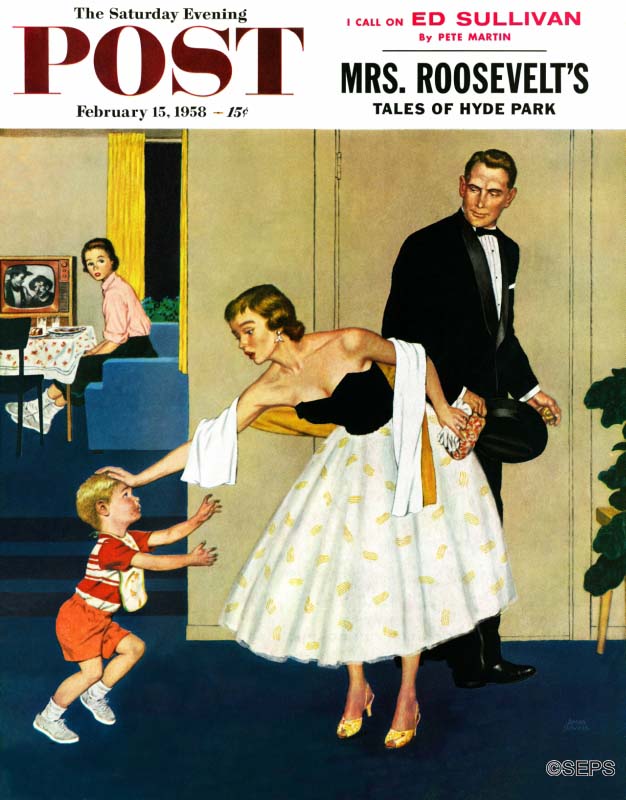

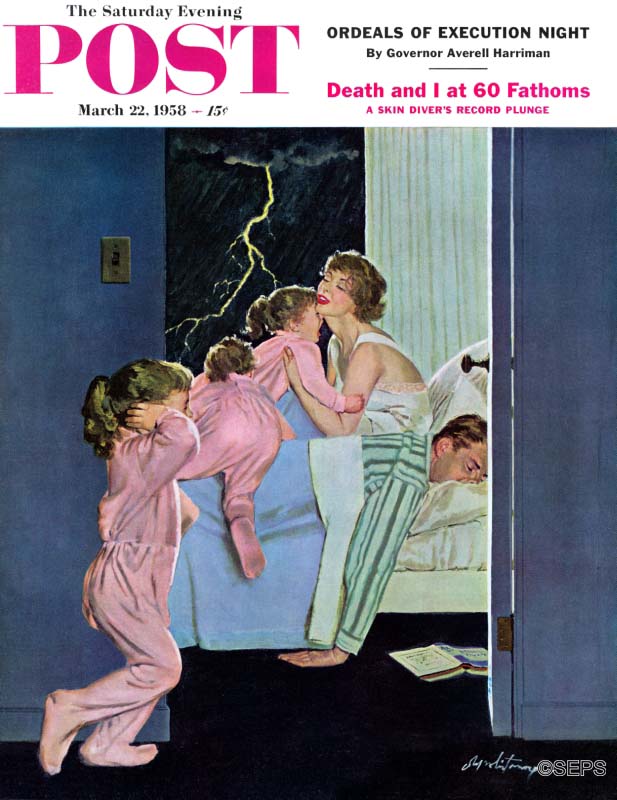

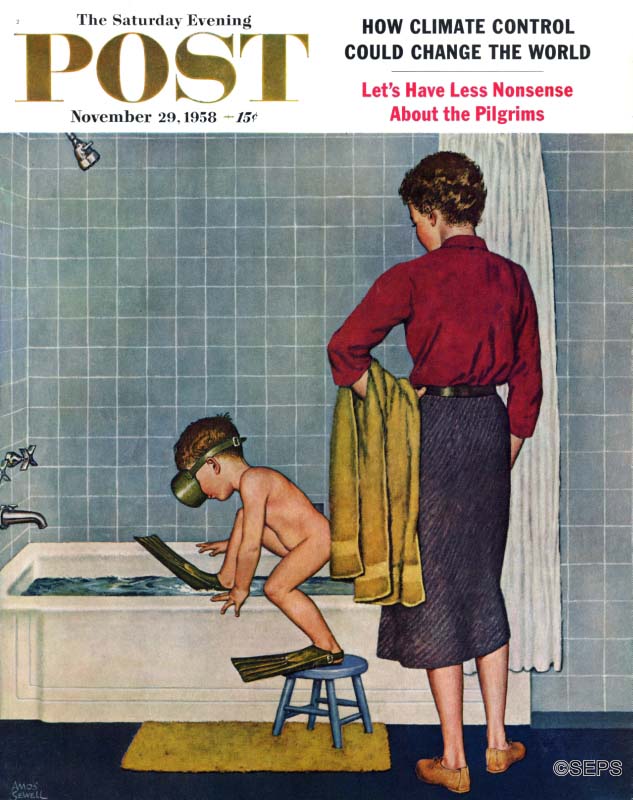

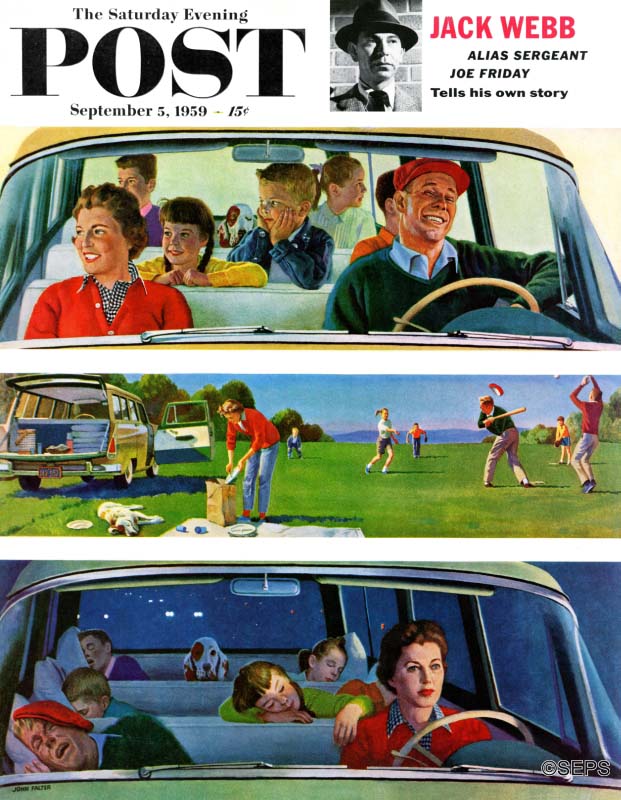

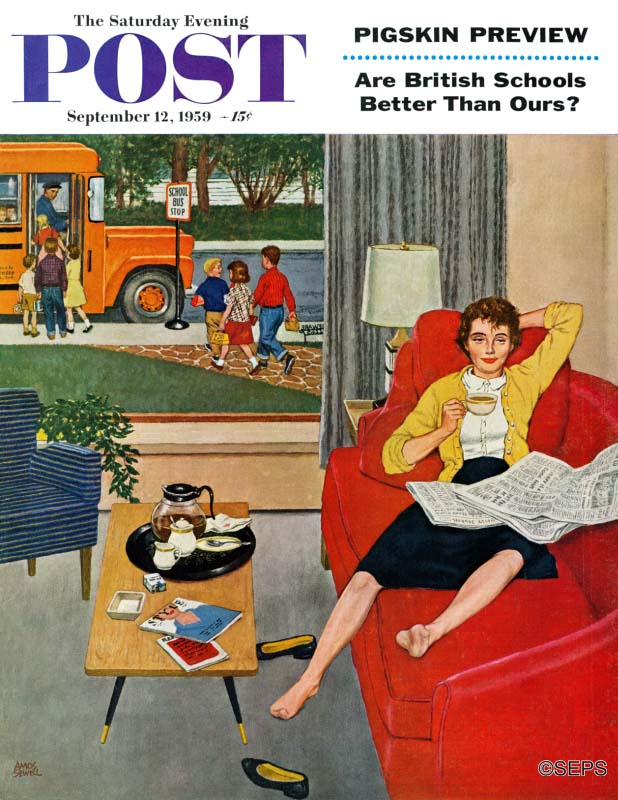

Mother’s Day

Moments with mom have taken center stage on The Saturday Evening Post cover throughout the 20th century. Norman Rockwell, Richard Sargent, George Hughes, Amos Sewell, and others have shown the special, sometimes challenging, and often humorous roles that moms play. As a salute to mothers everywhere, we present this look at moms on the covers of The Saturday Evening Post.

Celebrating Mom on the covers of The Saturday Evening Post (click on the covers to see larger image):

Did We Mortgage Our Identity? The 1960s Worries About Conformity

By the 1950s, it was clear the 20th century wasn’t going to be the era of peace and prosperity Americans had predicted in 1900. It had brought them a world war, a major depression, and another world war, and now an interminable cold war. Americans were getting tired of the constant belt-tightening and war preparedness; they wanted to enjoy the society they’d built. But many were disappointed with the society they found. There was a general sense that things could, and should, be better.

Even if Americans didn’t feel a troubling malaise, the media certainly made a case for it. Journalists continually wrote of problems in American society, such as racism, alienation, and materialism. They also referred to the problem of “conformity.”

There was no single definition of the term. Popular magazines and television talked of conformity as the desire to fit in: Americans, like their milk, were becoming homogenized. They were abandoning their individual differences to fit in and get ahead. A popular song of 1962, “Little Boxes,” talked of people, their lives, and their “ticky tacky” houses all looking the same. But conformity was more than just the desire to accommodate the mainstream of America.

Between 1959 and 1963, three authors, each highly regarded for his insight and judgment, weighed in on the subject.

Erich Fromm, the renowned psychologist and philosopher, wrote “Our Way Of Life Is Making Us Miserable” in 1964. The need to conform, he said, didn’t arise in Americans but in their organizations, which rewarded people…

who cooperate smoothly in large groups, who want to consume more and more, and whose tastes are standardized and can be easily influenced and anticipated. It needs men who feel free and independent, yet who arc willing to be commanded, to do what is expected to fit into the social machine without friction; men who can be guided without force, led without leaders, prompted without an aim except the aim to be on the move, to function, to go ahead.

Our society is becoming one of giant enterprises directed by a bureaucracy in which man becomes a small, well-oiled cog in the machinery. The oiling is done with higher wages, fringe benefits, well-ventilated factories and piped music, and by psychologists and “human-relations” experts; yet all this oiling does not alter the fact that man has become powerless, that he does not wholeheartedly participate in his work and that he is bored with it.

[We should give Fromm credit for recognizing his profession might be enabling the system by helping citizens endure an unfriendly system.]

The ‘organization man’ may be well fed, well amused and well oiled, yet he lacks a sense of identity because none of his feelings or his thoughts originates within himself; none is authentic. He has no convictions, either in politics, religion, philosophy or in love. He is attracted by the “latest model” in thought, art and style, and lives under the illusion that the thoughts and feelings which he has acquired by listening to the media of mass communication are his own.

He has a nostalgic longing for a life of individualism, initiative and justice, a longing that he satisfies by [watching cowboy movies.] But these values have disappeared from real life in the world of giant corporations, giant state and military bureaucracies and giant labor unions.

He, the individual, feels so small before these giants that he sees only one way to escape the sense of utter insignificance: He identifies himself with the giants and idolizes them as the true representatives of his own human powers, those of which he has dispossessed himself.

Such ideas aren’t particularly surprising, coming from a humanist and psychologist. But much of what he says was echoed by other Post contributors in the early 1960s, including a social critic from an unexpected quarter.