5 Times That Disease Unexpectedly Changed American History

Very few people foresaw the full impact of COVID-19 in America. And with the president’s recent announcement that he himself has been infected, there is much uncertainty about the repercussions his illness will have on his party, the government, the stock market, and the electorate.

But this is the nature of infectious diseases: the full impact of their arrival, departure, and consequences are rarely foreseen.

This has been seen repeatedly throughout history. During the Civil War, for example, America expected there’d be casualties from soldiers dying in the field of combat. What they didn’t expect was that most would die far from the fighting, as soldiers crowded in camps spread cholera, smallpox, and other infectious disease. More than half of the war dead were victims of disease.

Here are five times major illnesses had unexpected outcomes.

Malaria Fueled the American Slave Trade

Among the earliest European settlers to America were planters who arrived in South Carolina to grow rice. They soon discovered the marshy lowlands where they planted were infested malaria-bearing Anopheles mosquitoes. The disease, which reproduces in red blood cells, proved fatal for white workers in the fields, and planters had trouble maintaining their crops. But they discovered that recently enslaved Africans had a degree of immunity to malaria because of the genetic condition sickle-cell anemia. Rice became a successful crop, followed by cotton, both tended by slaves.

Planters didn’t know what gave the enslaved Africans their ability to endure malaria. They assumed it was because they were genetically hardier. This was far from true; half of all Black children born into American slavery died before reaching the age of five.

Disease Was a Sign of American Success

At the time of the Revolution, Americans enjoyed far better health than their contemporaries in Europe. The average height — a good indication of the state of health — was 68.1 inches, just one inch lower than the average height today (the average European measured 65.76 inches). Roughly 60 percent of children raised in the country survived to age 60. (page 123, “Deadly Truth”)

According to The Deadly Truth: A History of Disease in America by Gerald N. Grob, almost all Americans of the early 1800s resided in the country, leading exceptionally healthy lives. They lived far apart, with little exposure to strangers bearing illnesses; they had healthy diets and a clean environment.

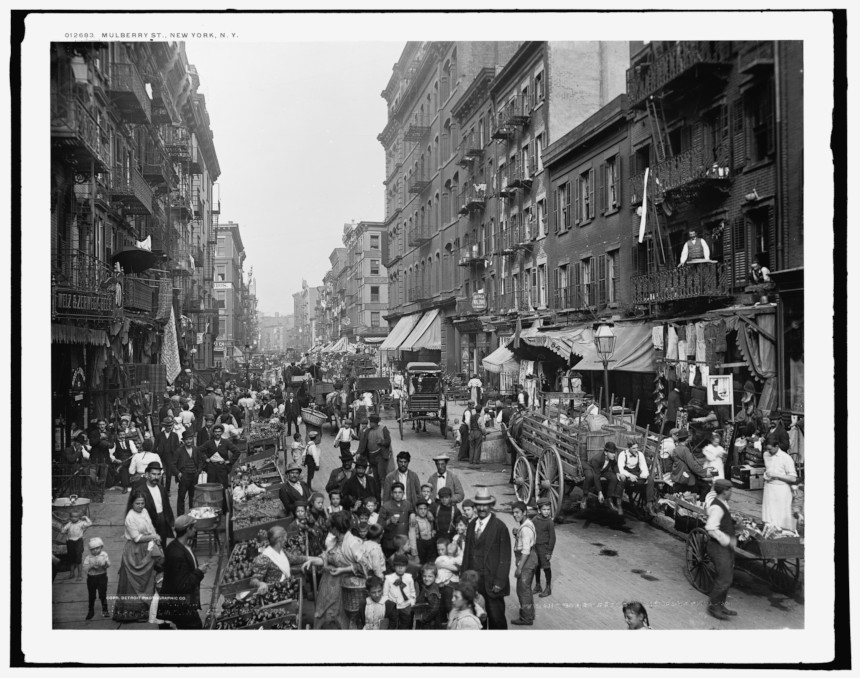

But the population began shifting toward the cities, according to Grob. Between 1800 and 1850, for instance, the population of Philadelphia increased 500 percent, consisting mostly of Americans leaving the country for the city. They were attracted by the commercial possibilities and the opportunity to enrich themselves beyond anything they could realize on a farm.

They came despite the already high risk of contracting a fatal disease in the city. Between 1721 and 1792, Boston was hit by seven epidemics. An outbreak of yellow fever in 1793 killed 1 in 10 Philadelphians.

Urban crowding made disease transmission easier. Water supplies became contaminated. Immigrants, sailors, and visitors brought fresh injections of diseases. Cholera and yellow fever spread rapidly, and cities didn’t have the resources to care for the sick. In big cities like New York and Boston, only 16 percent of children reached their 60th birthday. By 1830, the average male height in America had fallen to under 67 inches.

A Mysterious Illness in Midwestern Livestock Began Emptying Towns

In the 1800s, settlers in the Ohio River Valley noticed livestock sometimes developed a trembling in their legs that soon led to collapse and death. Shortly afterward, their owners showed the same signs, as well as abdominal pains and vomiting. Farmers called it “milk sickness” and believed it was caused by an infectious agent.

The disease proved highly fatal in pioneer settlements, sometimes claiming up to half the residents. Areas of Kentucky and Illinois were especially hard hit. One of its victims was Abraham Lincoln’s mother.

The disease abated as the land became settled and animals began grazing in pasture land instead of the wilderness. It wasn’t until 1923 that Dr. Anna Pierce Hobbs Bixby learned from a Shawnee woman the cause of the sickness. Sheep and cattle were eating snake root, a member of the daisy family, which contains tremetol, a poison so strong it can kill animals and lethally poison its meat and milk. But in the days before it was discovered, the flow of settlers stayed away from areas where milk sickness was reported.

Another Disease Brought Prosperity to Colorado

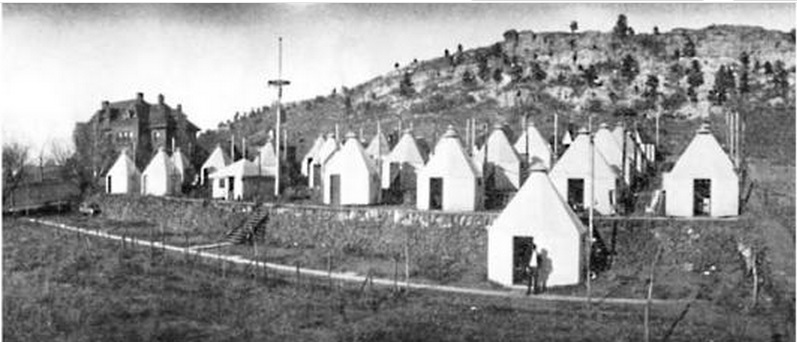

America’s number-one killer in the 1800s was tuberculosis. Doctors didn’t understand its cause or course, but it seemed to be connected with damp, polluted air. So doctors advised TB patients to move to higher altitudes, where the air was dry and conditions sunny. The recommendation was partly useful. The decreased oxygen levels at high altitudes slowed the growth of the mycobacterium-causing organism. And the sunlight and fresh air was always good for patients.

There were plenty of high altitudes and sunny weather in Colorado. Prior to the 1860s, it had been just another empty stretch of the western wilderness, sparsely peopled by miners and prospectors. But soon a growing number of sanitariums opened in Denver, Boulder, and Colorado Springs, and began to fill with tubercular patients. In time, they made up a third of the state’s population.

Cities grew up around the sanitariums, which attracted caregivers, support staff, and visitors to the patients. And TB patients often helped the town develop, bequeathing money to build streets and schools. In Denver alone, the population rose from 4,700 in 1870 to 106,000 in 1890.

Cleaning Up the Cities had Unintended and Fatal Consequences

Americans were shocked when a polio epidemic struck New England in 1916. For years, the incidence of the viral infections had declined almost to insignificance. Now, suddenly, 9,000 people had contracted the virus and 2,400 died — a fatality rate of 27 percent. The reason for the resurgence was completely unexpected.

Polio is caused by one of four viral strains. In the days before the Salk vaccine, most cases of polio ran their course in a day or two without serious complications. Only one case in 100 produced clinical symptoms, and even fewer caused paralysis. Most people experienced it as a low fever, headache, sore throat, and discomfort. But if the virus attacked the spine or the muscles controlling breathing, the consequences were quick and often fatal.

Up to the 1900s, most children in cities lived in crowded conditions and had been exposed to one of the strains at an early age. Or they gained immunity from maternal antibodies passed on to them as infants. Either way, most children growing up the congested cities were immune.

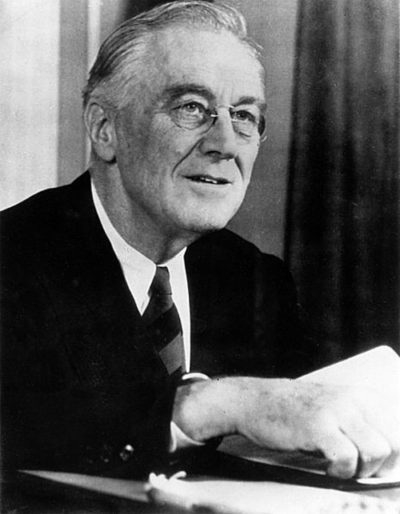

But as housing became less crowded and cleaner, there were fewer opportunities for exposure. A generation matured with little or no exposure and immunity. Polio swept through these communities quickly, striking down defenseless Americans. Franklin D. Roosevelt is a good illustration. He had grown up in wealth and comfort, and so had no immunity when the virus hit him in 1921 at the age of 39.

Featured image: Ward K, Armory Square Hospital, Washington, D.C., 1864 (Library of Congress)

The Saturday Evening Post History Minute: 4 Things You Didn’t Know About the Lincoln-Douglas Debates

Here are 4 interesting facts you might not know about these nation-defining debates from 160 years ago.

See more History Minute videos.

The 5 Most Memorable State of the Union Addresses

Ever since George Washington, the American president has given an annual message every year. It’s how he complies with the Constitution’s order that “from time to time,” he report on the state of the union and make “necessary and expedient” recommendations.

Originally delivered orally by the president, the annual report was submitted to Congress as a written document between 1800 and 1913. But President Wilson revived the tradition of personally reading the address.

Since then, there have been only few years when the President sent a written report.

This year, millions will watch Donald Trump’s address to hear what he has to say. If this address is like most, he will talk in broad terms of policy and propose laws that support his priorities.

Few, if any of those laws will make it out of committee. Out of 94 spoken addresses, only a handful made a lasting impression on America or the world.

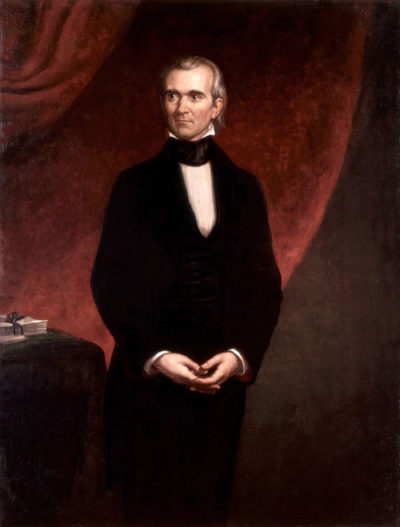

James Polk

President Polk’s fourth state of the union address in 1848 launched a massive migration westward. In ten years, the white population of California rose from 80 to 300,000 — because the president reported that the rumors of gold in California were true.

Polk said, “The accounts of the abundance of gold in that territory are of such an extraordinary character as would scarcely command belief were they not corroborated by the authentic reports of officers in the public service who have visited the mineral district and derived the facts which they detail from personal observation.”

Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln’s 1862 address expressed the principles for which northern men would fight and die over the next three years. It also set the bar for state of the union address for what is arguably the best prose ever written by a president:

“The dogmas of the quiet past are inadequate to the stormy present. The occasion is piled high with difficulty, and we must rise with the occasion. As our case is new, so we must think anew, and act anew. We must disenthrall ourselves, and then we shall save our country.

“Fellow-citizens, we cannot escape history. We of this Congress and this administration will be remembered in spite of ourselves. No personal significance, or insignificance, can spare one or another of us. The fiery trial through which we pass, will light us down, in honor or dishonor, to the latest generation…In giving freedom to the slave, we assure freedom to the free. We shall nobly save, or meanly lose, the last best hope of earth.”

Franklin Roosevelt

In 1942, President Roosevelt put the country’s wartime goals into words. Achieving these goals would be the full time job for 16 million Americans over the next three years. The U.S., Roosevelt said, was fighting to achieve four freedoms— not just the U.S. but for the entire world.

“Freedom of speech and expression…

“Freedom of every person to worship God in his own way…

“Freedom from want, which… means economic understandings which will secure to every nation a healthy peacetime life for its inhabitants…

“Freedom from fear… a world-wide reduction of armaments to such a point … that no nation will be in a position to commit an act of physical aggression against any neighbor—anywhere in the world.”

Lyndon Johnson

Few addresses touched as many American lives as the 1964 message from Lyndon Johnson, which launched his a highly ambitious “unconditional war on poverty.”

“Our aim,” he said, “is not only to relieve the symptom of poverty, but to cure it and, above all, to prevent it.”

In the months that followed, he pushed legislation that would expand the government’s role in civil rights, education, and health care. It would produce the Office of Economic Opportunity, Job Corps, VISTA, food stamp program, Medicare, and Medicaid.

Bill Clinton

Bill Clinton stunned Congress in his 1996 address when he announced “the era of big government is over.” It was a startling turn-around for the head of a party that had long supported increased government programs to address social ills. In the coming months, Clinton introduced spending cuts that pared back programs and enabled him to announce, in his 1998 address, that the government had balanced its books and was expecting a surplus. “What should we do with this projected surplus? I have a simple four-word answer: Save Social Security first.”

We should also mention, in passing, a few addresses that may not have directly affected Americans’ lives, but contained lines that proved ironic or all too true.

George W. Bush, in his 2003 address, identified Iraq, Iran, and North Korea as an “axis of evil” whose regimes were seeking “weapons of mass destruction.” It was a claim that would come back to haunt the administration when no such weapons were found in Iraq.

In 1974, Richard Nixon was under pressure from the Congressional Committee looking into the Watergate break-in. He told America, “I believe the time has come to bring that investigation and other investigations of this matter to an end. One year of Watergate is enough.” But it wasn’t enough for Congress. Seven months later, Nixon resigned.

In 1975, President Gerald Ford broke with the long tradition of presidents declaring the state of the union was strong. Ford had the courage to honestly say, “I want to speak very bluntly. I’ve got bad news, and I don’t expect much, if any, applause… the state of the Union is not good: Millions of Americans are out of work. Recession and inflation are eroding the money of millions more. Prices are too high, and sales are too slow. This year’s Federal deficit will be about $30 billion; next year’s probably $45 billion. The national debt will rise to over $500 billion.” It was the opening to an address that presented measures he felt would “rebuild our political and economic strength.”

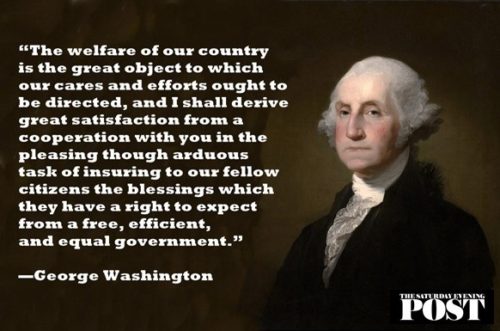

Finally, we should consider George Washington’s report from 1790, which some consider to be the ideal address. It was a concise: a thousand words long. (The longest address was given by President Clinton in 1995: 9,190 words. President Carter’s 1981 report, submitted in writing, exceeded 33,000 words.)

It offered practical advice, was short on flowery language or self praise, and concluded with this essential message that should inspire every president’s address to Congress:

“The welfare of our country is the great object to which our cares and efforts ought to be directed, and I shall derive great satisfaction from a cooperation with you in the pleasing though arduous task of insuring to our fellow citizens the blessings which they have a right to expect from a free, efficient, and equal government.”

3 Questions for Ken Burns

Ken Burns first gained national attention and acclaim with his 1981 PBS special on the construction of the Brooklyn Bridge — a show that earned him an Oscar nomination. Since then, Burns has turned his eye to numerous aspects of American history from the Civil War to baseball and prohibition. His latest project, The Address, focuses on a school that helps learning-disabled kids by challenging them to memorize and deliver the Gettysburg Address.

Jeanne Wolf: What got you interested in history?

Ken Burns: My mother died of cancer when I was 11. That is a crucible that still affects me. I think about her every day. I wouldn’t be doing what I do if had I not had to go through the pain of anticipating of her death and, then, all the years of trying to not deal with it. So, what do I do for a living? I wake the dead. I make films that make Abraham Lincoln and Jackie Robinson come alive. Who else do you think I’m trying to wake up?

JW: Why do your films always seem to go beyond the bare facts?

KB: We live in a rational world in which one plus one equals two. But if we examine our hearts or our art, we find that we really want one plus one to equal three. The combination of two things — a man and a woman in love, brush strokes on a canvas, the emotion of a song — we want it to add up to something more. I’m always reaching for those moments in life and in film.

JW: There’s a lot of cynicism about world leaders and politicians past and present. Do they deserve it?

KB: We think that our heroes should be perfect, but if you go back to the Greeks you discover that heroes aren’t perfect. They have very obvious strengths and maybe not so obvious weaknesses, and it’s the negotiation between those two that defines heroism — whether it’s Abraham Lincoln or the Roosevelts or, for a more current example, Chris Christie. But studying the past arms you with a kind of optimism, because when people say, “It’s so bad right now with this economic meltdown that it’s like the Depression,” I can answer, “No, it’s not. During the Great Depression, in some cities, the animals in the zoo were shot and the meat distributed to the poor. Is that happening now?”

The world is chaotic and we’re trying to figure out some order. The painter puts a frame around it; the playwright puts a proscenium arch above it; a documentarian puts it on a screen. We invent stories, we tell them to each other. We achieve a kind of immortality with the stories that we tell and that’s the way we abolish the wolf at the door that’s gonna come knocking eventually.

Cartoons: Nice Try

Abraham Lincoln said you could fool some of the people all the time and all of the people some of the time, but you cannot fool all of the people all of the time. But gracious, how some people will try!

"Sorry, but 'What happens in Vegas, stays in Vegas'

is not a recognized legal precedent."

"Uhh ... excuse me ma'am, but you've ... uh ... taken my cart by mistake. I believe that’s yours over there."

"Before reading the will of the dear departed,

I would like very much to make an offer for that fine animal."

"But honey! I bought it for you!"

"Consider this.

If I go on this diet and exercise program,

I might get so healthy you could lose me

as a regular customer."

"I'll be willing to work for nothing,

just to learn the business."

The First Memorial Day

During the week of April 10, 1865, The Saturday Evening Post was struggling to keep up with the war news. One jubilant story, “A Week Of Triumph,” had already been set on page 4 when even greater news arrived. The editors moved copy on the facing page so they could print “Latest News/Surrender of Lee And His Army.”

Yet even as it celebrated the triumph of the Union, the Post stopped to consider a more somber aspect of the victory: “Know that the glad bells are but a death knell to many whose souls are filled with darkness and gloom, to many who sacrificed their earthly all on the Altar of their Country. Think you! will the return of our brave heroes bring unalloyed joy to those whose brave and dear ones will never return? Oh! the misery, the wretchedness, the unspeakable loneliness is too awful to contemplate.”

Three years after the war ended, a fraternal organization of Union veterans called for a national “Decoration Day” on May 30th. Members of the Grand Army of the Republic were urged to decorate “the graves of comrades who died in defense of their country during the late rebellion.”

The observation of Decoration Day, eventually renamed Memorial Day, gained new importance with each war, and over the decades the Post often ran articles reminding Americans of their debt to the war dead. In a 1956 article, for example, the editors wrote, “Long after the agony of Bunker Hill, Bull Run, and Bastogne, the dead lie in peace. They and their comrades have left us names the world can never forget: Shiloh, Château-Thierry, Iwo Jima, the Normandy Beachhead, and the Pusan Perimeter. We gave the ground they lie in; they hallow it. Afternoon shadows lengthen on Memorial Day, somewhere faintly a bugle blows taps, and we renew the resolve Abraham Lincoln bequeathed us: that ‘these dead shall not have died in vain.’ ”

Since these words were published, many more Americans have died serving their country, from Khe Sanh to Kuwait, and are still under fire in Afghanistan and Iraq. In total, more than 43 million Americans have served in our armed forces, of which 653,000—roughly 15 percent—died in battle, a number that changes with each conflict overseas.

How should we honor the memory of these men and women? The strewing of flowers on graves that was so often practiced after the Civil War gave way over the years to parades, brass bands, speeches, and rifle salutes. Author Evan Hill considered these practices in the May 28, 1960 issue as he looked back on his long recuperation after World War II (see “My Memorial Day”).

“Each Memorial Day, and on other days, too, when memories come tumbling back, we remember the dead. Too often we hear patriotic phrases composed of empty words, spoken with an empty shallowness; and these are disappointing days. …

“At these times I think of Big Ed Manifold of York, Pennsylvania, my company commander in France, who in our rare rest periods sat near his slit trench reading stacks of The New York Times, eating huge chunks of quartermaster bread spread with sweet French butter, and washing them down with cognac. Big Ed was killed outside Lunéville while holding his wire sergeants’ wounded head in his arms, protecting him from artillery fire. …

“It may be comforting to organize our patriotic feelings, setting aside certain minutes in a certain month to honor our dead. But to me—and, I believe, to the hundreds of combat-wounded men I knew during four years in Army hospitals—the parades and ceremonial rifle volleys sometimes seem to be parodies.”

Evan’s discomfort with the way America honors its veterans was echoed years later by Private Jessica Lynch. Testifying to Congress on the distorted accounts of her wounding and capture issued by the government, she said, “The truth of war is not always easy to hear, but it is always more heroic than the hype.”

Legislation in 1968 shifted Memorial Day from May 30th to the last Monday in May. The act was intended to create three extended weekends (the other two being President’s Day and Veteran’s Day). Memorial Day has since become, unofficially, the first weekend of summer, and the original intent has been partly obscured by the beginning of the vacation season.

In recent years, though, special events have tried to revive the original purpose of the day. The first Memorial Day parade in 60 years was held in Washington in 2004. In 2000, Congress passed the National Moment of Remembrance resolution, which calls for Americans to pause at 3 p.m., EST, on Memorial Day, either in silence or listening to Taps. And many Americans—veterans and civilians—continue to push Congress to return Memorial Day back to its own day and back to its original, dedicated purpose.

Abraham Lincoln: A Tribute

It’s a big year for our 16th president. Throughout the year, the Lincoln Bicentennial (www.lincolnbicentennial.gov) will celebrate his life, his work, and his words. Considered among the most revered Americans of all time, Lincoln continues to captivate our imagination and inspire the nation. Our 44th president counts Abraham Lincoln among his list of heroes, even placing his hand on the same burgundy-velvet-bound Bible that President Lincoln used at his first inauguration.

On the 200th anniversary of his birth, our nation continues to strive to advance Lincoln’s ideal to build a more perfect union. Certainly, that was the goal of the February 10, 1945 Post article Thoughts on Peace on Lincoln’s Birthday. The commemorative feature presented ideas on peace of two great Americans.

A Lincoln scholar who published a Pulitzer Prize-winning biography of Honest Abe, Carl Sandburg found his inspiration for the poem The Long Shadow of Lincoln presented in the Post feature from one of the president’s messages to Congress in 1862. Artist Norman Rockwell drew inspiration from the last paragraph of Lincoln’s Second Inaugural Address that reads: “With malice toward none; with charity for all; with firmness in the right, as God gives us to see the right, let us strive on to finish the work we are in; to bind up the nation’s wounds; to care for him who shall have borne the battle, and for his widow, and his orphan — to do all which may achieve and cherish a just and a lasting peace, among ourselves, and with all nations.”

In the introduction to the article, Post editors wrote: “In the heart-lifting symbolism of Norman Rockwell’s great painting there is thought for all of us. For here we find not only the crippled soldier who must learn a new way of life, the builder who will help put a shattered world together, the teacher and her brood, and the sorrowing family of a fallen warrior, but also the hand of brotherhood extended to the downtrodden and, in the background, the less fortunate races of humankind who must not be forgotten if peace is to be anything more than an armistice. Here, in the faces and attitudes of these people, are determination and tolerance and the yearning for a better world.”