Very few people foresaw the full impact of COVID-19 in America. And with the president’s recent announcement that he himself has been infected, there is much uncertainty about the repercussions his illness will have on his party, the government, the stock market, and the electorate.

But this is the nature of infectious diseases: the full impact of their arrival, departure, and consequences are rarely foreseen.

This has been seen repeatedly throughout history. During the Civil War, for example, America expected there’d be casualties from soldiers dying in the field of combat. What they didn’t expect was that most would die far from the fighting, as soldiers crowded in camps spread cholera, smallpox, and other infectious disease. More than half of the war dead were victims of disease.

Here are five times major illnesses had unexpected outcomes.

Malaria Fueled the American Slave Trade

Among the earliest European settlers to America were planters who arrived in South Carolina to grow rice. They soon discovered the marshy lowlands where they planted were infested malaria-bearing Anopheles mosquitoes. The disease, which reproduces in red blood cells, proved fatal for white workers in the fields, and planters had trouble maintaining their crops. But they discovered that recently enslaved Africans had a degree of immunity to malaria because of the genetic condition sickle-cell anemia. Rice became a successful crop, followed by cotton, both tended by slaves.

Planters didn’t know what gave the enslaved Africans their ability to endure malaria. They assumed it was because they were genetically hardier. This was far from true; half of all Black children born into American slavery died before reaching the age of five.

Disease Was a Sign of American Success

At the time of the Revolution, Americans enjoyed far better health than their contemporaries in Europe. The average height — a good indication of the state of health — was 68.1 inches, just one inch lower than the average height today (the average European measured 65.76 inches). Roughly 60 percent of children raised in the country survived to age 60. (page 123, “Deadly Truth”)

According to The Deadly Truth: A History of Disease in America by Gerald N. Grob, almost all Americans of the early 1800s resided in the country, leading exceptionally healthy lives. They lived far apart, with little exposure to strangers bearing illnesses; they had healthy diets and a clean environment.

But the population began shifting toward the cities, according to Grob. Between 1800 and 1850, for instance, the population of Philadelphia increased 500 percent, consisting mostly of Americans leaving the country for the city. They were attracted by the commercial possibilities and the opportunity to enrich themselves beyond anything they could realize on a farm.

They came despite the already high risk of contracting a fatal disease in the city. Between 1721 and 1792, Boston was hit by seven epidemics. An outbreak of yellow fever in 1793 killed 1 in 10 Philadelphians.

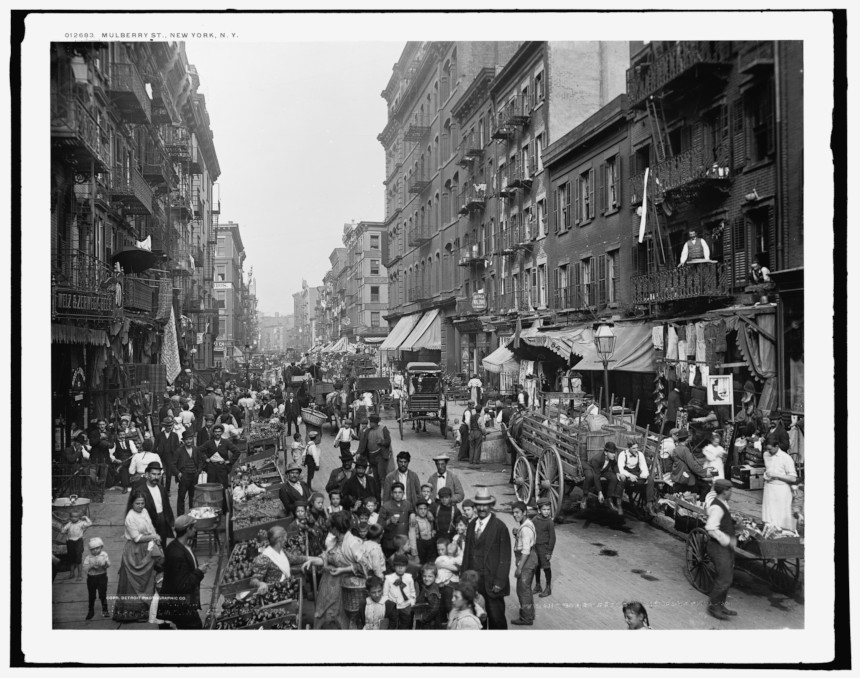

Urban crowding made disease transmission easier. Water supplies became contaminated. Immigrants, sailors, and visitors brought fresh injections of diseases. Cholera and yellow fever spread rapidly, and cities didn’t have the resources to care for the sick. In big cities like New York and Boston, only 16 percent of children reached their 60th birthday. By 1830, the average male height in America had fallen to under 67 inches.

A Mysterious Illness in Midwestern Livestock Began Emptying Towns

In the 1800s, settlers in the Ohio River Valley noticed livestock sometimes developed a trembling in their legs that soon led to collapse and death. Shortly afterward, their owners showed the same signs, as well as abdominal pains and vomiting. Farmers called it “milk sickness” and believed it was caused by an infectious agent.

The disease proved highly fatal in pioneer settlements, sometimes claiming up to half the residents. Areas of Kentucky and Illinois were especially hard hit. One of its victims was Abraham Lincoln’s mother.

The disease abated as the land became settled and animals began grazing in pasture land instead of the wilderness. It wasn’t until 1923 that Dr. Anna Pierce Hobbs Bixby learned from a Shawnee woman the cause of the sickness. Sheep and cattle were eating snake root, a member of the daisy family, which contains tremetol, a poison so strong it can kill animals and lethally poison its meat and milk. But in the days before it was discovered, the flow of settlers stayed away from areas where milk sickness was reported.

Another Disease Brought Prosperity to Colorado

America’s number-one killer in the 1800s was tuberculosis. Doctors didn’t understand its cause or course, but it seemed to be connected with damp, polluted air. So doctors advised TB patients to move to higher altitudes, where the air was dry and conditions sunny. The recommendation was partly useful. The decreased oxygen levels at high altitudes slowed the growth of the mycobacterium-causing organism. And the sunlight and fresh air was always good for patients.

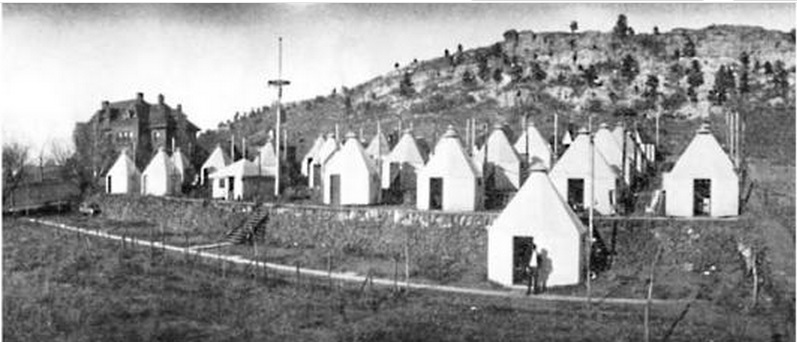

There were plenty of high altitudes and sunny weather in Colorado. Prior to the 1860s, it had been just another empty stretch of the western wilderness, sparsely peopled by miners and prospectors. But soon a growing number of sanitariums opened in Denver, Boulder, and Colorado Springs, and began to fill with tubercular patients. In time, they made up a third of the state’s population.

Cities grew up around the sanitariums, which attracted caregivers, support staff, and visitors to the patients. And TB patients often helped the town develop, bequeathing money to build streets and schools. In Denver alone, the population rose from 4,700 in 1870 to 106,000 in 1890.

Cleaning Up the Cities had Unintended and Fatal Consequences

Americans were shocked when a polio epidemic struck New England in 1916. For years, the incidence of the viral infections had declined almost to insignificance. Now, suddenly, 9,000 people had contracted the virus and 2,400 died — a fatality rate of 27 percent. The reason for the resurgence was completely unexpected.

Polio is caused by one of four viral strains. In the days before the Salk vaccine, most cases of polio ran their course in a day or two without serious complications. Only one case in 100 produced clinical symptoms, and even fewer caused paralysis. Most people experienced it as a low fever, headache, sore throat, and discomfort. But if the virus attacked the spine or the muscles controlling breathing, the consequences were quick and often fatal.

Up to the 1900s, most children in cities lived in crowded conditions and had been exposed to one of the strains at an early age. Or they gained immunity from maternal antibodies passed on to them as infants. Either way, most children growing up the congested cities were immune.

But as housing became less crowded and cleaner, there were fewer opportunities for exposure. A generation matured with little or no exposure and immunity. Polio swept through these communities quickly, striking down defenseless Americans. Franklin D. Roosevelt is a good illustration. He had grown up in wealth and comfort, and so had no immunity when the virus hit him in 1921 at the age of 39.

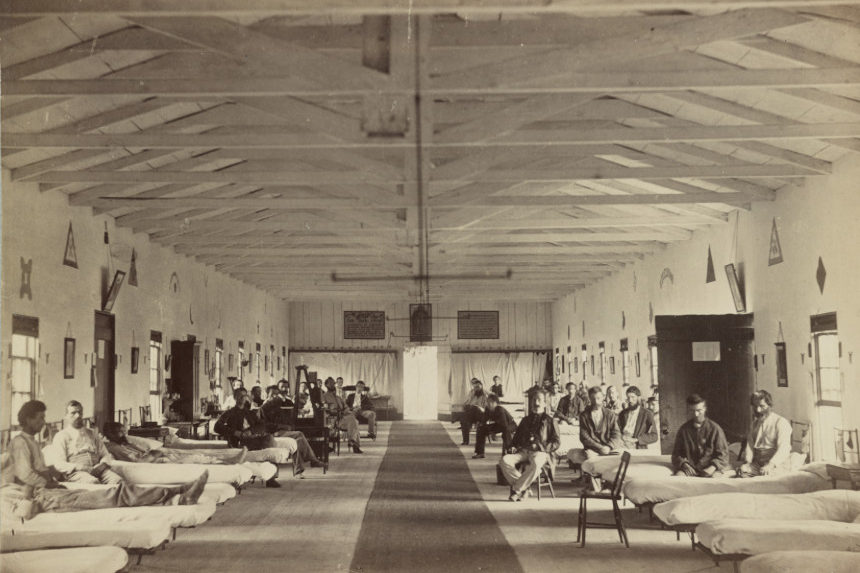

Featured image: Ward K, Armory Square Hospital, Washington, D.C., 1864 (Library of Congress)

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

A fascinating and sobering look at diseases reaching across the centuries. Although many have been eradicated in this country through the progression of medical science and immunization, many (like cholera and malaria) are still terrible killers in other parts of the world. Thank God for Doctors Without Borders and their constant work.

Unfortunately, even today in the U.S., many black Americans (in particular) don’t have access to proper medical care which would include preventative immunizations to keep them healthier and at less risk for health problems otherwise. This needs to be a basic focus for racial equality moving forward as much as anything else.

Disease is doesn’t care who you are, how rich or poor, what position of power you hold or don’t. Even Presidents aren’t immune, be it 1921 or 2020. It’s something we always need to be aware of; past, present and future. Right now it’s Covid-19, but there are others waiting in the wings to strike, and they will. Then there are the “old” ones that seem to be under control, but will resurge given the chance; not unlike prisoners plotting their breakout escape at this very moment.