Considering History: Dorothy Day and the True Spirit of Christmas

This series by American studies professor Ben Railton explores the connections between America’s past and present.

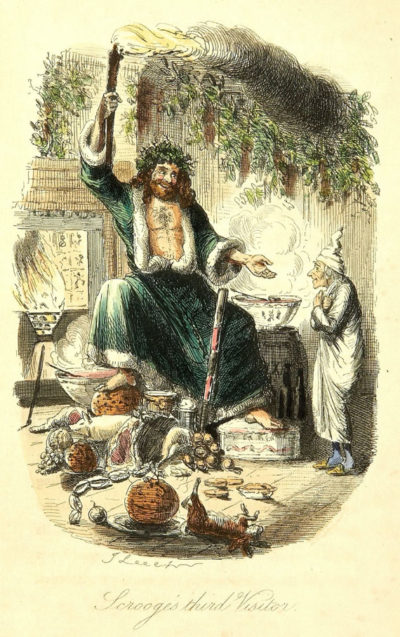

Charles Dickens’ novel A Christmas Carol (1843) is one of the most enduring and popular holiday stories, but its central anti-poverty theme is too often forgotten. Ebenezer Scrooge learns a number of lessons in the course of the novel, but the most poignant and powerful are those he learns from the Cratchit family about the horrors of poverty. As the Ghost of Christmas Present puts it, after quoting Scrooge’s own despicable sentiments about “the surplus population” back at him when it comes to the question of young Tiny Tim’s survival, “It may be, that in the sight of Heaven, you are more worthless and less fit to live than millions like this poor man’s child. Oh God! to hear the Insect on the leaf pronouncing on the too much life among his hungry brothers in the dust!”

This holiday season has seen a renewal of longstanding American debates over whether and how to collectively, publicly celebrate Christmas. In many ways those debates represent a constructed distraction, an attempt to divide Americans over issues that are not in fact in dispute (we are and have always been free to celebrate whatever holidays we choose in whatever manner we’d like). But if we take to heart the lessons of Dickens’ holiday tale, we can use them during this season to celebrate an American whose life exemplifies the true spirit of Christmas: Dorothy Day.

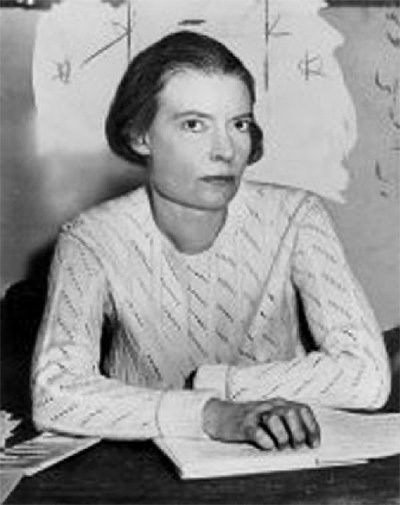

Born in Brooklyn and raised in Oakland and Chicago, Day (1897-1980) was an avid reader with an abiding interest in both social justice and Catholicism (which she explored on her own, culminating in her December 1927 baptism). She attended the University of Illinois for two years, but left college in 1916 to move to New York and join the budding socialist movement there. She worked for radical publications including The Masses and The Liberator, took part in numerous activist campaigns including the women’s suffrage movement (with which she was arrested and tortured in November 1917 for picketing outside the White House). She also wrote an autobiographical novel, The Eleventh Virgin (1924), which chronicled her fraught early 1920s affair with a fellow activist (Lionel Moise), including her difficult choice to have an abortion when she became pregnant.

All these early experiences illustrated Day’s attempts to combine personal reflection and spirituality with communal activism and social justice. But it was in the depths of the Great Depression that Day and a fellow radical Catholic activist would create a movement that truly exemplified those pursuits. In 1932 Day met Peter Maurin, an itinerant French monk and theologian who had recently immigrated to the U.S. from Canada. In collaboration with Maurin, Day developed the idea for a Catholic social movement dedicated both to confronting poverty and inequality and giving the working class the tools to advocate for their own liberation and justice. She launched that movement with the inaugural issue of a new newspaper, The Catholic Worker, published on May Day (May 1st), 1933.

In that newspaper’s first editorial, Day wrote, “For those who think that there is no hope for the future, no recognition of their plight, The Catholic Worker is being edited. It is printed to call their attention to the fact that the Catholic church has a social program.” The newspaper, like the movement it launched, advocated for labor actions, legal protections for workers and the poor, and radical charitable efforts, such as the St. Joseph House of Hospitality, the no-questions-asked soup kitchen and shelter that Day founded at the same time as the newspaper and ran for many decades thereafter. “Our rule,” Day wrote, “is the works of mercy.”

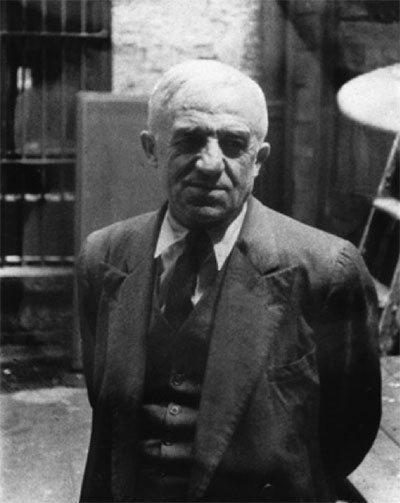

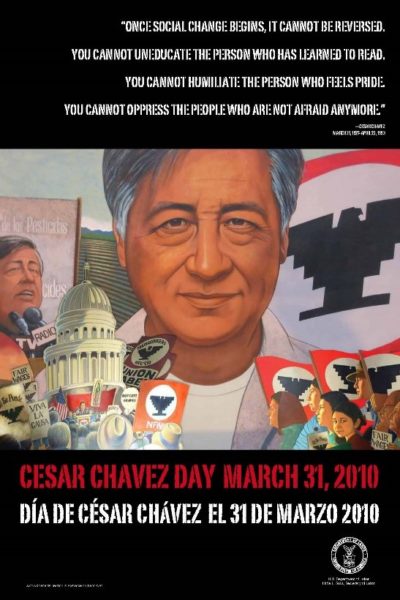

Day edited The Catholic Worker from its first issue through her death in 1980, and over those decades published and amplified the writings of such influential thinkers and activists as Thomas Merton and Daniel Berrigan. Day’s social justice activism extended far beyond the pages of the paper, however, as illustrated by her arrests at civil disobedience protests in 1955 (for refusing to participate in mandatory Cold War civil defense drills) and 1973 (at the age of 75, while picketing alongside labor leader Cesar Chavez in California). In response to such efforts, as well as her support for the Civil Rights Movement, her anti-Vietnam War pacifism, and more, the Jesuit magazine America dedicated an entire 1972 issue to Day, noting, “By now, if one had to choose a single individual to symbolize the best in the aspiration and action of the American Catholic community during the last forty years, that one person would certainly be Dorothy Day.”

Daniel Berrigan (Thomas Good / NLN via the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International, 3.0 Unported, 2.5 Generic, 2.0 Generic and 1.0 Generic license.)

Day also consistently modeled the kinds of thoughtful, critical self-reflection that is at the heart of lifelong spiritual pursuits and personal growth (as Scrooge learns from his three Ghosts). She did so as early as that 1924 autobiographical novel The Eleventh Virgin; but it was in her full autobiography, 1952’s The Long Loneliness, that she analyzed the many stages of her evolving identity, Catholicism, and activism with particular honesty and eloquence. As she writes in the opening chapter, “Confession,” “Going to confession is hard. Writing a book is hard, because you are ‘giving yourself away.’ But if you love, you want to give yourself. You write as you are impelled to write, about man and his problems, his relation to God and his fellows. You write about yourself because in the long run all man’s problems are the same, his human needs of sustenance and love.”

Day called that book “an account of myself, a reason for the faith that is in me.” Her self and her faith were likewise in the Catholic Worker movement, in her lifelong commitment to social justice, in her consistent attention to American communities too often left out of our conversations. Those efforts, like Day’s life and career, exemplify the true spirit of American spirituality and community, a spirit well worth celebrating in this holiday season.

Featured image: Dorothy Day, 1916 (Wikimedia Commons)

Considering History: U.S. Imperialism and Puerto Rican Activism

This series by American studies professor Ben Railton explores the connections between America’s past and present.

Fifty years ago, on July 26, 1969, the Puerto Rican community organization known as the Young Lords opened their New York chapter. Originating out of early 1960s Chicago street gangs, the Lords had been formally constituted in Chicago in September 1968, on the 100th anniversary of the Grito de Lares rebellion against the Spanish in Puerto Rico. But it was with the opening of the New York chapter that the Lords truly came into their own as a national social and political activist movement, as illustrated by that chapter’s July 27 “Garbage Offensive” protests against the city’s substandard garbage collection services in Puerto Rican and other minority neighborhoods.

The 50th anniversary of those events offers us a chance to remember these Civil Rights era communities and campaigns and better understand both Puerto Rico’s relationship to the United States and Puerto Rican political and social activism, in an era when both those topics have become central national conversations once more.

The relationship between the U.S. and Puerto Rico began with the late 1890s events of the Spanish American War. Although the majority of that conflict was fought in the Philippines and Cuba (Teddy Roosevelt’s famous charge up San Juan Hill took place in Cuba, not in Puerto Rico’s capital city of the same name), U.S. forces did invade and occupy the coastal town of Guánica on July 25, 1898. And in the February 1899 Treaty of Paris that formally ended the war, Spain ceded Puerto Rico along with the Philippines and Guam to the United States.

The relationship that followed was a clearly colonial and imperial one throughout the 20th century, with the U.S. ruling the island through both the military and U.S.-appointed governors. The 1900 Foraker Act did create a House of Delegates that would be directly elected by Puerto Rican voters, but the island’s upper chamber (initially an executive council that gradually evolved into a senate) and governor continued to be appointed directly by the United States government. Similarly, the island continued to have no voting representation in Congress, a fact that became particularly significant when through a series of racist “Insular Cases” the Supreme Court and U.S. government deemed Puerto Rico “territory appurtenant and belonging to the United States, but not a part of the United States” as the island was “inhabited by alien races.” This ambiguous and fraught status, “foreign in a domestic sense” as the Court put it, left Puerto Ricans with far fewer Constitutional rights than their mainland counterparts.

Two moments in the 1910s reflect the evolution and ongoing effects of that fraught relationship between Puerto Rico and the United States. In 1914 the House of Delegates voted unanimously in favor of independence from the U.S., but the U.S. Congress rejected the vote as a violation of the Foraker Act. Three years later, Congress passed the 1917 Jones Act, which granted U.S. citizenship to all Puerto Ricans born after April 25, 1898. But the law was opposed by the entire Puerto Rican House of Delegates, which saw it as a cynical strategy to make it possible for the U.S. to draft Puerto Rican young men into World War I military service. While that motive was certainly present and while the law did not change the island’s overall colonial status (indeed, it reinforced U.S. control, another reason the House of Delegates unanimously opposed the law), it nonetheless contributed to evolving possibilities of U.S. citizenship for Puerto Ricans.

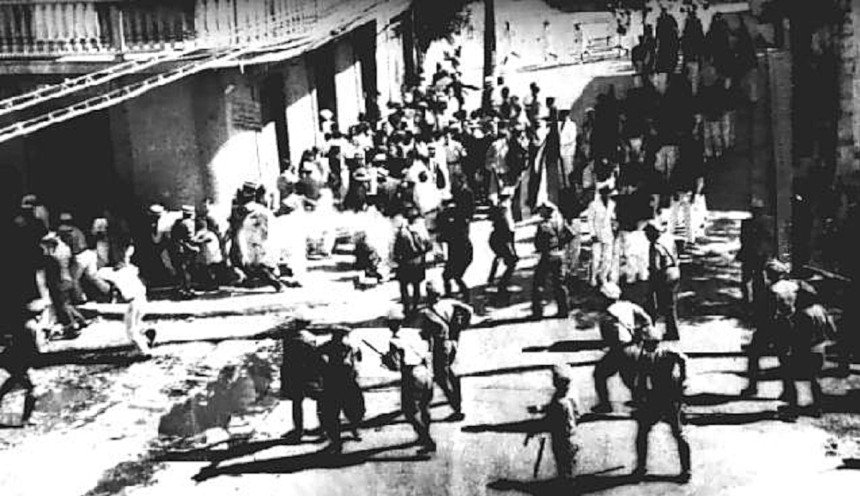

Alongside those legal and governmental histories, the early 20th century likewise witnessed a number of Puerto Rican social and political uprisings. Pedro Albizu Campos, leader of the Puerto Rican Nationalist Party and a principal advocate for Puerto Rican control of its own government and affairs, was particularly instrumental in organizing such efforts, including a 1935 protest at the University of Puerto Rico and a 1937 mass action in the city of Ponce. At the latter protest, Puerto Rican Insular Police opened fire on the protesters, killing 19 and wounding hundreds in what has come to be known as the Ponce massacre. These and other events led to gradual shifts in the U.S.-Puerto Rican relationship, including President Truman’s 1946 appointment of the first Puerto Rican-born governor, Jesús T. Piñero, and a subsequent 1947 amendment of the Jones Act that allowed Puerto Ricans to directly elect their own governors.

Throughout these decades, and even more so in the years after World War II, many Puerto Ricans moved to the mainland U.S., forming sizeable communities in cities like Chicago and New York and bringing with them the legacies of these contentious relationships. 1960s groups like the Young Lords embodied Puerto Rican activist opposition to governmental control and racist oppression. It’s no coincidence that the group’s first 1968 efforts in Chicago were in response to the city government’s evictions of Puerto Rican residents and police brutality against the community as part of Mayor Daley’s urban renewal campaign, trends that the Lords and their Chicago leader Jose Cha Cha Jimenez countered with arguments for Puerto Rican self-determination and community leadership.

With the 1969 founding of the New York chapter, those efforts became truly collective and national, and would continue throughout the next decade. Most famously, New York Young Lords leader Vicente “Panama” Alba was instrumental in both orchestrating and speaking in response to the October 1977 takeover of the Statue of Liberty by 30 Puerto Rican nationalists, a group advocating for both specific actions (such as the release of five political prisoners who had been held by the U.S. government for more than 25 years) and broader ideas of Puerto Rican self-determination and independence. To quote Alba himself, speaking to a documentarian 35 years after the takeover, “the end result was that the picture of the Puerto Rican flag [on the Statue’s forehead], and the issue of Puerto Rico being a slave nation and colony, … became an international issue.”

In 2019, thanks to both the failed federal response to the devastations of 2017’s Hurricane Maria and the ongoing, stunning mass protests against Governor Ricardo Rosselló, Puerto Rico has become a national and international topic once more. These and other unfolding stories need the historical contexts of the Young Lords’ 1960s and 70s activism, and of the dual legacies of U.S.-Puerto Rican relations and Puerto Rican resistance that have led to both their moment and ours.

Featured image: Qzonkos via Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license / Wikimedia Commons

Considering History: Voices and Stories of the Mexican-American Experience

This series by American studies professor Ben Railton explores the connections between America’s past and present.

In the prior two posts in this series on Myths and Realities of the Mexican-American Border and Mexican Americans as Political Prop in the 20th and 21st Centuries, I’ve traced the Mexican-American border’s constructed and contested nature, the border patrol’s origins and initial role in the Chinese Exclusion era, and the use of Mexican Americans as a political prop throughout the 20th century. These histories form a vital backdrop for any conversations about the border and immigration, and as a result need to be more fully understood in our heated contemporary moment.

Yet one element is largely missing from those posts: the voices and stories of Mexican Americans themselves. In each historical period, we find compelling stories that certainly highlight the effects of our most exclusionary national policies but that also exemplify how Mexican Americans have fought for their own and their community’s rights within an evolving America.

María Amparo Ruiz de Burton Depicts the Mexican-American Experience

The first Mexican-American author to publish fiction in English, María Amparo Ruiz de Burton, experienced first-hand and wrote about the late 19th century aftermath of the Mexican-American War and the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo. The daughter and granddaughter of Mexican generals and political leaders, after the Treaty a teenage Ruiz moved north to Alta California with her family. She met and married an American military officer, and they began operating a ranch just outside of California. But he was injured during the Civil War and died shortly thereafter, and when Ruiz de Burton returned to California with her two children she found that Anglo squatters had occupied the ranch (a far too common experience for Mexican-American landowners in the era).

For the remainder of her life Ruiz de Burton fought legal and political battles to regain and secure her ranch and land claims. At the same time, she published a number of literary works, including two compelling novels: Who Would Have Thought It? (1872), which uses the story of an adopted mixed-race girl to satirize Anglo-American ideals and prejudices; and The Squatter and the Don (1885), which highlights the experiences of both Anglo arrivals and Mexican landowners in post-Treaty California. While these novels do not shy away from the harshest realities of late 19th century Mexican American life, Ruiz de Burton also portrays an American future that includes (and in Squatter romantically unites) all these cultures and communities.

Stories from the Mexican Repatriation Program

The Mexican Repatriation program of the 1930s represented one of the first national policies that sought instead to exclude Mexican Americans from that shared future. Francisco Balderrama and Raymond Rodríguez’s Decade of Betrayal: Mexican Repatriation in the 1930s (1995) features the stories of many of the millions of Mexican Americans (a majority of them birthright citizens) affected by this exclusionary policy. In one telling moment in the book, Southern California radio host José David Orozco and his guest Dr. José Díaz share stories of married couples and families separated by the region’s deportation sweeps. And the policy’s effects were felt nationwide, as illustrated by a groundbreaking 1973 study of the near-complete destruction of the Mexican-American community in Gary, Indiana (where many had been employed by U.S. Steel).

The Successes of the League of United Latin American Citizens

Many Mexican Americans fought back against the era’s discriminations. Founded in February 1929 in Corpus Christi, Texas, the League of United Latin American Citizens (LULAC) was modeled in part on the National Association for the Advanced of Colored People (NAACP). Two founding members, Pedro and María Hernández, were particularly instrumental in developing LULAC’s multilayered social and political agenda: María, an elementary school teacher and mother of ten, focused on educational outreach and support for expectant and new mothers; Pedro, a political and legal activist, organized a successful lawsuit challenging the Texas legislature’s longstanding policy of excluding Mexican Americans from juries. Over the next decades LULAC would extend those efforts: creating community education and preschool programs (such as the popular Little School of the 400 program); conducting voter registration campaigns and opposing efforts to disenfranchise Hispanic voters; suing school districts that denied Mexican-American students equal access and opportunities; and advocating for both basic rights and full citizenship for Mexican and Hispanic Americans. Two of their successful educational lawsuits, Mendez v. Westminster (1945) and Minerva Delgado v. Bastrop Independent School District (1948), helped create the precedents that would lead to the Supreme Court’s turning point anti-segregation decision in Brown v. Board of Education (1954).

Many Mexican Americans fought back against the era’s discriminations. Founded in February 1929 in Corpus Christi, Texas, the League of United Latin American Citizens (LULAC) was modeled in part on the National Association for the Advanced of Colored People (NAACP). Two founding members, Pedro and María Hernández, were particularly instrumental in developing LULAC’s multilayered social and political agenda: María, an elementary school teacher and mother of ten, focused on educational outreach and support for expectant and new mothers; Pedro, a political and legal activist, organized a successful lawsuit challenging the Texas legislature’s longstanding policy of excluding Mexican Americans from juries. Over the next decades LULAC would extend those efforts: creating community education and preschool programs (such as the popular Little School of the 400 program); conducting voter registration campaigns and opposing efforts to disenfranchise Hispanic voters; suing school districts that denied Mexican-American students equal access and opportunities; and advocating for both basic rights and full citizenship for Mexican and Hispanic Americans. Two of their successful educational lawsuits, Mendez v. Westminster (1945) and Minerva Delgado v. Bastrop Independent School District (1948), helped create the precedents that would lead to the Supreme Court’s turning point anti-segregation decision in Brown v. Board of Education (1954).

The Bracero Program Sparks Activism

The Bracero Program was series of agreements between the U.S. and Mexico that promised decent living conditions to Mexicans who came to the U.S. to fulfill a labor shortage in agriculture, starting in the 1940s. It brought new Mexican Americans to the U.S., and they added their voices to this evolving story. The National Museum of American History’s wonderful exhibition, Bittersweet Harvest: The Bracero Program 1942-1964, captured many bracero voices and experiences, documenting each stage of bracero life from the journey and the border to brutal conditions, labor activism, and multi-generational family legacies. One quote, from former bracero Guadalupe Mena Arizmendi, sums up both the program’s realities and its possibilities: “Es puro sufrimiento, le digo, allí sí se sufre y allí andamos, eso queríamos (I tell you, it is pure suffering, there you suffer and there we were, that is what we wanted).” Mexican-American author Tomás Rivera, himself the son of braceros, portrays the community’s experiences and legacies with grit and power in his novel And the Earth Did Not Devour Him (1971).

Out of the Bracero Program and era came as well the first moves toward national activism on behalf of migrant laborers. Dolores Huerta, the daughter of a migrant laborer father and a mother who ran a hotel and restaurant for migrant workers, founded the Agricultural Workers Association in 1960 when she was just 30 years old; two years later she joined forces with César Chávez, the son of two migrant laborers and then the Executive Director of the activist Community Service Organization, to co-found the National Farm Workers Association (NFWA). A few years later, the NFWA joined striking Filipino-American laborers from the Agricultural Workers Organizing Community (AWOC) in the 1965 Delano (CA) grape strike, a hugely influential effort that would last nearly five years, lead to the founding of the United Farm Workers (UFW) when the two groups merged, and fundamentally reshape late 20th century American labor and politics.

Operation Wetback’s Legacy

These decades continued to witness anti-Mexican-American discrimination and exclusionary policies, most notably the mid-1950s federal deportation program known as Operation Wetback. Historian Mae Ngai’s award-winning Impossible Subjects: Illegal Aliens and the Making of Modern America (2004) features the stories of many of those affected by Operation Wetback. She highlights, for example, a July 1955 incident in which “some 88 braceros died of sunstroke as a result of a roundup that had taken place in 112-degree heat, and … more would have died had Red Cross not intervened.” Elsewhere she quotes a congressional investigation that referred to a ship transporting deportees to Mexico as the equivalent of “an eighteenth century slave ship” and a “penal hell ship.” LULAC’s newsletter depicted deportees arriving in Mexico as “broken men, with strength spent and exhausted by the senseless struggles of a life revolving around slavish, ill-paid labor, and the degradation of jail and prison cells.”

The Accomplishments of the National Council of La Raza

These evolving exclusionary policies required new activist organizations, and the 1960s saw the creation of a vital one: the National Council of La Raza. La Raza was also the name of a community newspaper edited by Eliezer Joaquin Risco Lozada, a prominent young activist in Fresno who would go on to open rural health clinics throughout the region, create the first La Raza Studies (later Chicano Studies) program at Fresno State University, and advocate for Latino-American rights throughout his inspiring life. In March 1968, inspired by Lozada and other activists, Southern California high school students led the East Los Angeles Walkouts, a stunning and successful mass action that garnered national attention and made clear that Mexican- and Latin-American communities were fully part of the era’s burgeoning civil rights movements.

Writers Chronicle Mexican-American Life

The late 20th and early 21st centuries saw the emergence of a number of Mexican-American creative writers who brought these histories, stories, and communities into their ground-breaking literary works. Novelist Rolando Hinojasa has created, across the 15 volumes to date in the Klail City Death Trip Series, a fictional border county and community modeled on the South Texas Rio Grande Valley in which he grew up. Scholar and activist Gloria Anzaldúa likewise grew up in the Rio Grande Valley, and turned that border setting into the basis for her multi-lingual multi-genre masterpiece Borderlands/La Frontera: The New Mestiza (1987) among many other works. And Professor Norma Cantú, the foremost translator of and scholar on Anzaldúa’s works, has published her own memoirs as both a Mexican-American immigrant and a 21st century contributor to the continuing story of Mexican-American identity and community.

As part of his trip to the Rio Grande Valley and the border last week, President Trump visited Anzalduas Park, a county park along the river. Perhaps this historical moment can produce more than further border and immigration debates—perhaps it can lead us to more collective engagement with the story of Gloria Anzaldúa and other Mexican-American figures and communities. Their voices deserve a far more central role in our collective memories, our present conversations, and our shared future.

Note: This piece benefited greatly from the suggestions of Professors Laura Belmonte and John Buaas.

Considering History: Anti-Semitism and Jewish American Activism

This column by American studies professor Ben Railton explores the connections between America’s past and present.

Today Jews around the world celebrate Yom Kippur, the Jewish Day of Atonement and the end of the High Holidays for 2018. Here in the United States, the holiday period has seen continuations of two distinct but interconnected trends: troubling instances of anti-Semitism, from the chants of “Jews will not replace us” at the 2017 Unite the Right rally in Charlottesville to the staggering upswing in anti-Semitic incidents on college campuses; and striking moments of Jewish American activism, as with the Rosh Hashanah sermon delivered by Stephen Miller’s childhood rabbi (Neil Comess-Daniels) in which the religious leader calls out Miller’s ideas and policies as “completely antithetical to everything I know about Judaism, Jewish law, and Jewish values.”

Each of these moments has a great deal to tell us about both the Jewish American experience specifically and American politics and society more broadly in 2018. But they also connect to longstanding and under-remembered American histories of both anti-Semitism and Jewish American activism, two threads that emerged with particular clarity in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

As my colleague Michael Hoberman traces in his book New Israel/New England: Jews and Puritans in Early America, Jewish Americans have been an influential community since the nation’s earliest post-contact origins. But it was the final decades of the 19th century and opening ones of the 20th that the Jewish American community truly exploded in size, thanks in particular to waves of immigration from Eastern and Southern Europe. Between 1880 and 1925 more than 2.8 million Jews immigrated to the United States, many fleeing anti-Semitic attitudes and violence in Europe. By the turn of the century these immigrants had turned communities such as New York City’s Lower East Side into some of the largest Jewish neighborhoods in the world.

As those Jewish American communities became more sizeable and prominent, so too did instances and trends of American anti-Semitism become more widespread. Leading voices in the nascent Populist movement frequently blamed Jewish “financiers” such as the Rothschilds for the era’s increasing ills of inequality and stratification, culminating in a scandal during the 1896 presidential campaign when sitting President Grover Cleveland was revealed to have sold bonds to a so-called banking “syndicate.” Founded just two years earlier, the xenophobic Immigration Restriction League focused many of its attacks on new Jewish arrivals, describing them for example as “beaten men from beaten races, representing the world failures in the struggle for existence.” These trends continued into the early 20th century and contributed significantly to the 1921 and 1924 Quota Acts, the nation’s first overarching immigration laws and ones that severely limited arrivals from Eastern and Southern Europe.

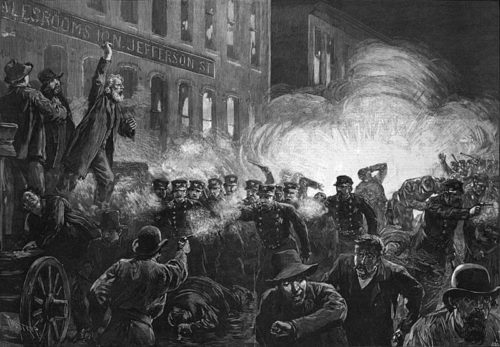

Late 19th century anti-Semitism was also deeply intertwined with collective fears of “anarchists,” labor movement organizers, and other radical figures and influences in American society. Descriptions of the eight radical journalists and anarchists arrested and tried for the May 1886 Haymarket Square bombing, for example, consistently emphasized their “foreign” and “alien” identities and perspectives. This collective prejudice added one more chilling layer to comments like this one, in a New York Times editorial on the case: “In the early stages of an acute outbreak of anarchy a Gatling gun, or if the case be severe, two, is the sovereign remedy. Later on hemp, in judicious doses, has an admirable effect in preventing the spread of the disease.” And indeed, despite the trial’s farcical qualities all eight defendants were convicted, with seven sentenced to hang (three were eventually pardoned but four others were hung).

Jewish Americans did play a key role in the early labor movement and other influential activist efforts. Some of the earliest and most prominent national labor leaders were Jewish American, including Samuel Gompers (a Sephardic Jew who had immigrated to the U.S. from England during the Civil War and became the first leader of the American Federation of Labor after its December 1886 founding) and Daniel DeLeon (an immigrant from Curaçao who became a leading figure in the groundbreaking Socialist Labor Party). More radical but just as influential was Emma Goldman, who immigrated from Russia to New York City in 1885 at the age of 16 and went on to become one of the turn of the century’s most famous activists, organizers, and writers (and also an open opponent of organized religion, making clear that there were many distinct threads in this Jewish American community).

Abraham Cahan extended Jewish American activism into the realms of journalism. Cahan was a towering turn of the century figure who deserves a far more central place in our collective memories. Cahan immigrated from Lithuania to New York’s Lower East Side in 1882 at the age of 22, fleeing a wave of anti-Semitic pogroms after the assassination of Russia’s Czar Alexander II. He quickly became active in labor and socialist movements, and in 1897 founded and began editing a weekly socialist newspaper, The Jewish Daily Forward. Named after a prominent British Social Democratic paper, the Forward (or Forverts) was published entirely in Yiddish, wedding its portrayals of Jewish American identity and community to its radical politics in clear and defining ways.

Although those politics were never absent from the Forward’s pages, Cahan made clear that the paper, the first American periodical published in Yiddish, had a broader role to play in the Jewish American community as well. The paper, he wrote, must “interest itself in the things that the masses are interested in when they aren’t preoccupied with the daily struggle for bread.” As a result he made sure to include sections on literature and culture, family and relationships, and, most famously, the advice section the “Bintel Brief” (or “bundle of letters”). In this column, Cahan himself answered reader letters on virtually every topic under the sun, including many relating directly to the multi-cultural experiences of Jewish American arrivals, families, and communities.

Cahan brought those same multi-layered interests and subjects to his literary career. Works like the 1898 short story “A Sweatshop Romance” depict the worlds of work and labor activism in fictionalized but still radical and political ways, linking audience sympathies for the story’s working class immigrant protagonists to their implicit support for labor movement concerns and efforts. But in his socially and psychologically realistic novels, especially his masterpiece The Rise of David Levinsky (1917), Cahan broadens his scope to depict many different themes and stages within the immigrant and Jewish American stories, while also linking them to shared subjects such as the American Dream, “rags to riches” ideals and realities, and more.

Indeed, what Cahan’s writings ultimately reveal is just how fundamentally American Jewish American experiences, communities, and activism are — a point that, now as then, offers a vital counter to anti-Semitic fears and hostilities.