This series by American studies professor Ben Railton explores the connections between America’s past and present.

As I discussed in my last column, when the Mexican-American border began to be patrolled in the early 1900s, the explicit and sole focus was on the only immigrants defined as “illegal” during that era: first Chinese and eventually most Asian arrivals to the United States. When the Immigration Act of 1924 extended those limitations and exclusions, additional nationalities became targets for the newly formalized Border Patrol. But arrivals from the Western Hemisphere were overtly exempt from that law, meaning that Mexicans and other Central and South Americans could still cross the border more freely (and U.S. residents could likewise cross to Mexico with ease).

All that would soon change, however. Beginning in the 1920s, and continuing throughout the 20th and into the 21st centuries, debates over the Mexican-American border would shift significantly, focusing on arrivals from Mexico and other Latin American nations. Moreover, those debates and the resulting policies have consistently fluctuated between xenophobic fears of Hispanic arrivals and cynical attempts to capitalize on them as a labor force, leaving the immigrant individuals, families, and communities themselves too often outside of these conversations.

A 1928 speech on the House floor from Texas Congressman John Box exemplified the shift to anti-Latin-American narratives. Arguing that the new national quotas should be amended to include Mexico and other Western Hemisphere nations, Box thundered, “Every reason which calls for the exclusion of the most wretched, ignorant, dirty, diseased, and degraded people of Europe or Asia demands that the illiterate, unclean, peonized masses moving this way from Mexico be stopped at the border.” Box went further, elucidating a number of the xenophobic stereotypes that have become standard fare for anti-immigrant arguments:

Another purpose of the immigration laws is the protection of American racial stock from further degradation or change through mongrelization. … This blend of low-grade Spaniard, peonized Indian, and Negro slave mixes with Negroes, mulattoes, and other mongrels, and some sorry whites, already here. The prevention of such mongrelization and the degradation it causes is one of the purposes of our laws which the admission of these people will tend to defeat. … To keep out the illiterate and the diseased is another essential part of the Nation’s immigration policy. The Mexican peons are illiterate and ignorant. Because of their unsanitary habits and living conditions and their vices they are especially subject to smallpox, venereal diseases, tuberculosis, and other dangerous contagions. Their admission is inconsistent with this phase of our policy. … The protection of American society against the importation of crime and pauperism is yet another object of these laws. Few, if any, other immigrants have brought us so large a proportion of criminals and paupers as have the Mexican peons.

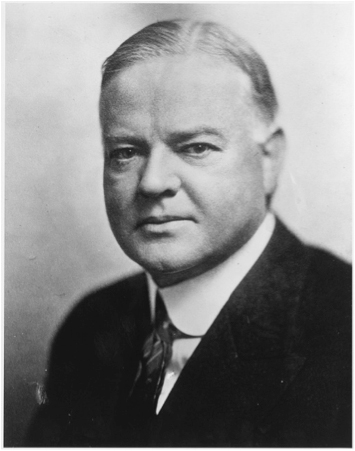

Box’s xenophobic and nativist narratives were taken up by a number of prominent cultural voices, including a contributor to the Saturday Evening Post. In a series of 1929 and 1930 articles, including “We Must Be on Our Guard” and “The Mexican Invasion,” anti-immigration activist Roy L. Garis extended Box’s cases for excluding Mexican arrivals and expelling Mexican Americans. Inspired by such cultural fears, and galvanized by the Great Depression and its accompanying economic and labor crises, in late 1929 President Herbert Hoover launched the Mexican Repatriation program. By 1936 at least half a million Mexican Americans (a majority of them birthright citizens) had been deported to Mexico; some scholarly estimates place the number as high as two million. At least 10,000 per year would continue to be deported until the program’s 1940 conclusion.

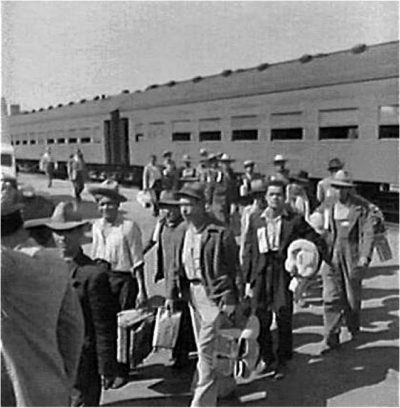

Just two years later, however, with the Depression over and World War II underway, the United States desperately needed additional labor forces, and the pendulum swung once more. On August 4th, 1942, the U.S. signed the Mexican Farm Labor Agreement with Mexico, creating the Bracero (“manual laborer”) Program through which Mexican laborers were guaranteed the chance to enter the U.S. and certain basic protections such as food, shelter, and a minimum wage of 30 cents per hour. The program was extended and amplified by the 1951 Migrant Labor Agreement, and by its end in 1964, an average of 200,000 braceros were being brought to the U.S. per year. Yet these arrivals not only had no ability to advocate for their own rights as laborers (attempts at action such as a 1943 strike alongside Japanese workers in Dayton, Washington were ruthlessly squashed), but likewise were offered no chance of becoming permanent residents or American citizens.

Even during this era of heightened need for and importation of Mexican laborers, continued anti-Mexican sentiments and fears of “illegal” immigrants produced xenophobic federal policies. The most extreme of these was 1954’s Operation Wetback, a policy initiated by President Eisenhower’s new Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS) Commissioner Joseph Swing. Swing was a former World War II general who had fought against Pancho Villa during the 1916 “Mexican Punitive Expedition,” and he created Operation Wetback in an attempt to drastically enhance border patrols and amplify the number of deportations of Mexican Americans. In 1954 alone the program produced more than 1 million “returns,” defined as “confirmed movement of an inadmissible or deportable alien out of the United States not based on an order of removal.” Although deportations did not continue at that level, and indeed were countered by additional arrivals throughout the period, Swing’s program exemplified the continued presence of anti-Mexican sentiments even in the Bracero era.

The swings between those kinds of policies and programs, and the concurrent use of Mexican Americans as a political prop, have continued for the last half-century. Just a year after the Bracero Program ended, the Immigration and Naturalization Act of 1965 did away with national quotas, creating instead a system of preferences that aided some Mexican arrivals (those with family connections) but severely limited many others (due to an emphasis on particular kinds of educational and professional backgrounds). As a result of the latter policy, many businesses began relying more and more on undocumented immigrants, a pattern that continued unabated until the 1986 Immigration Reform and Control Act sought to curtail such practices and give some undocumented immigrants a path toward legal status. Needless to say, the issue has in no way been resolved since then, with the failed 2006 Comprehensive Immigration Reform Act as an illustration. That proposed bill attempted to thread the needle, ramping up border security and patrols while offering both new guest worker programs and a path to legal status for undocumented immigrants already in the U.S., but that last provision in particular was viewed by many members of Congress as an “amnesty” and led to the bill’s defeat in the House of Representatives.

Noteworthy in each of those eras is the absence, or at least minimization, of Mexican- and other Latin-American voices within them. Each of those repatriated Mexican Americans, each of the Braceros, each of those affected by Operation Wetback is not only an individual but a part of families, communities, American identity and history. In an era when Mexican and Latin Americans and the Mexican-American border have once again become a political prop, it is long past time to remember and tell the stories of those individuals and communities. I’ll highlight a few in my third and final post in this series.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now