Considering History: Remembering the History of Slavery Is Both Necessary and Patriotic

This series by American studies professor Ben Railton explores the connections between America’s past and present.

Since its August 2019 launch, the New York Times Magazine’s 1619 Project, an initiative that examines the consequences of slavery in the United States, has received many different responses, including pushback and critique, from a wide variety of sources. But over the last few weeks, a new challenge has emerged: the Woodson Center’s 1776 Project, a collaboration between a number of African-American journalists, entrepreneurs, and academics (although it features no historians). As Woodson Center founder and 1776 Project creator Bob Woodson puts it, in a direct rebuke to the 1619 Project’s emphasis on slavery’s enduring legacy, the 1776 Project is intended to “challenge those who assert America is forever defined by past failures.” “We seek,” the project’s mission statement adds, “to offer alternative perspectives that celebrate the progress America has made on delivering her promise of equality and opportunity.”

In other words, the 1776 Project seeks to create an explicit dichotomy between remembering the histories of slavery and moving forward, arguing that focusing on those histories (the 1619 Project’s central goal) makes continuing our shared progress more difficult. The 1776 Project also strives to distinguish between criticisms of America’s past and celebrations of its promise. In this Martin Luther King Day column, I made the case for critical patriotism, which is critiquing America’s failures (past as well as present) in order to move the nation closer to its ideals. Here, I want to make a parallel case for challenging why better remembering our most horrific histories is both necessary and patriotic.

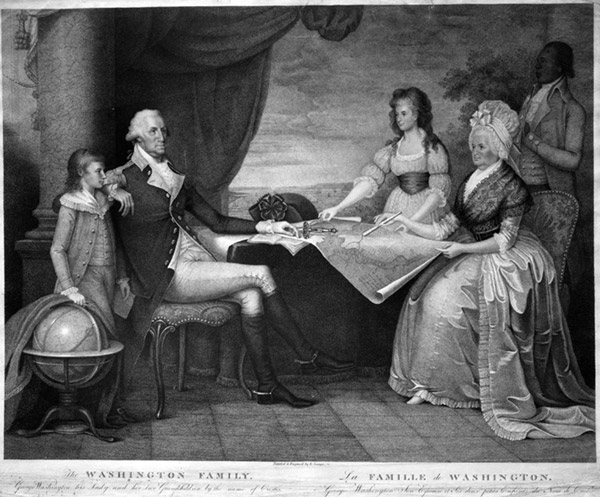

Offering a particularly striking illustration of the defining interconnections between slavery and America’s origins is Founding Father George Washington. It’s not just that Washington was a slave-owner, and thus subject to the same critiques I leveled against his peer Thomas Jefferson. Instead, it’s that in perhaps his most significant role as the nation’s first president, Washington was even more thoroughly defined by his choices within that horrific and destructive system.

Washington was inaugurated and began serving his first presidential term in New York City, the new nation’s capital, in 1789. But the July 1790 Residence Act shifted the capital to Philadelphia for the next ten years, during which time a permanent capital would be constructed in Washington, D.C. When it came to slavery, Pennsylvania was distinct from the rest of the nation, having passed the 1780 Act for the Gradual Abolition of Slavery, a law which, along with a 1788 Amendment, made it illegal for a non-resident slave-owner to hold slaves for longer than six months (after six months’ residency, any such enslaved people would become free). Washington argued that since he was only in the state due to his presidential role, he should not be subject to that law; but fearing that his slaves would nonetheless be freed, he devised a plan to rotate all slaves back to Virginia just before they reached that six-month threshold, keeping them all enslaved.

At least one of those enslaved African Americans directly resisted that practice, using instead the household’s Philadelphia location to escape from slavery and the Washingtons. That woman, Ona Judge, is the subject of Erica Dunbar’s magisterial book Never Caught: The Washingtons’ Relentless Pursuit of Their Runaway Slave, Ona Judge (2017). As Judge put it in an 1845 interview with the abolitionist New Hampshire newspaper The Granite Freeman, “Whilst they were packing up to go to Virginia, I was packing to go, I didn’t know where; for I knew that if I went back to Virginia, I should never get my liberty.” After Judge escaped, President Washington devoted considerable time and resources to seeking her re-capture and re-enslavement, even refusing an offer (made by Judge through intermediaries) that she would return if she were promised freedom upon the Washingtons’ death. Although she was indeed never caught, she would remain a fugitive throughout her life.

![Runaway Advertisement for Oney Judge, enslaved servant in George Washington's presidential household. The Pennsylvania Gazette, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, May 24, 1796. "Advertisement. ABSCONDED from the houshold [sic] of the President of the United States, ONEY JUDGE, a light mulatto girl, much freckled, with very black eyes and bushy black hair. She is of middle stature, slender, and delicately formed, about 20 years of age. She has many changes of good clothes of all sorts, but they are not sufficiently recollected to be described—As there was no suspicion of her going off, nor no provocation to do so, it is not easy to conjecture whither she has gone, or fully, what her design is;—but as she may attempt to escape by water, all matters of vessels are cautioned against admitting her into them, although it is probable she will attempt to pass as a free woman, and has, it is said, wherewithal to pay her passage. Ten dollars will be paid to any person who will bring her home, if taken in the city, or on board any vessel in the harbour;—and a reasonable additional sum if apprehended at, and brought from a greater distance, and in proportion to the distance. FREDERICK KITT, Steward. May 23 [illegible]."](https://www.saturdayeveningpost.com/wp-content/uploads/satevepost/2020-02-24-Oney_Judge_Runaway_Ad-wikimedia-commons.jpg)

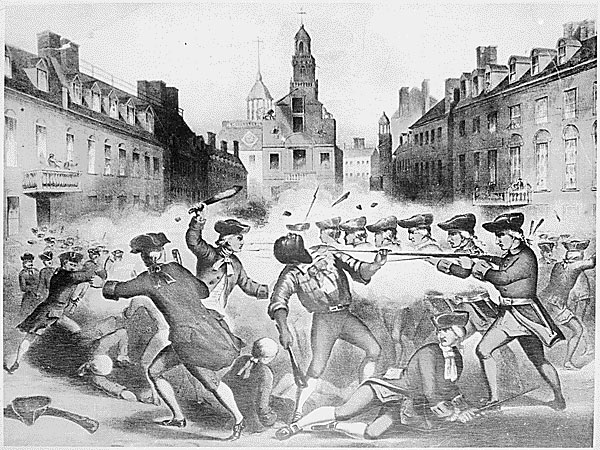

Another American who was fleeing that same system in search of those same ideals happens to be one of the most prominent individuals associated with the origins of the American Revolution and the new nation: Crispus Attucks. Attucks gained fame when he was shot and killed at the March 5, 1770, events that came to be known as the Boston Massacre. Attucks is often described as “the first casualty of the American Revolution.” As we approach the 250th anniversary of the Massacre, it’s worth noting that Attucks’s status as a fugitive slave has been much less consistently highlighted in that famous narrative of this iconic Revolutionary figure.

While some details of Attucks’s life remain hazy, others are clear and historically significant. His father was apparently an enslaved African (Prince Yonger) and his mother (Nancy Attucks) a Native American of the Natick tribe; Nancy may or may not have been enslaved as well, but in any case such a mixed-race child was defined by the colony’s laws in the era of Attucks’s 1720s birth as a “black,” and thus he was enslaved from birth on a Framingham farm. In 1750 the roughly 27-year-old Attucks ran away from slavery, which we know because his master, William Brown, placed an advertisement describing Attucks and seeking his return. Although Brown warned that “all Matters of Vessels and others, are hereby cautioned against concealing or carrying off said Servant on Penalty of Law,” Attucks not only remained a fugitive for the next 20 years but became a sailor as well as a ropemaker at Boston’s seaport.

That role and setting are certainly part of what led Attucks to King’s Street in March 1770, as many of the protesters were sailors. But how much would our narratives of Attucks as a defining member of that pre-Revolutionary protest, as “the first casualty of the American Revolution,” shift if we likewise foregrounded his status as a fugitive slave — as a man who had been born into that world, had escaped it in his quest for liberty, and faced every day after the possibility of being recaptured into that tyrannical system? And how much would our narratives of the Boston Massacre and the Revolution shift as well? At the October 1770 trial of the British soldiers charged with murder, their defense lawyer, future founder and president John Adams, critiqued Attucks’s “mad behavior,” arguing that his “very looks was [sic] enough to terrify any person.” But indeed, Attucks’s actions and identity were neither mad nor terrifying, but representative of both the worst and the best of America, at our founding moment and ever since.

Featured image: National Archives at College Park / Public domain

Considering History: Carter Woodson, Black History Month, and Reframing the American Story

This series by American studies professor Ben Railton explores the connections between America’s past and present.

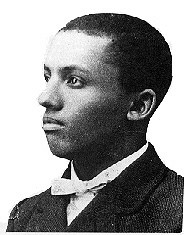

Although the first Black History Month was celebrated in February 1970, the original concept behind this commemoration of African American history and community is nearing its centennial anniversary. In 1926, pioneering African American educator, historian, and activist Carter G. Woodson (1875-1950) decided to designate the second week of February “Negro History Week.” That week features the birthdays of both Frederick Douglass and Abraham Lincoln, and so provided a perfect occasion in which public schools—the central emphasis of Woodson’s idea—could remember those figures specifically and African American history more generally.

But Woodson did so much more than designate a special week. Many of Woodson’s own experiences, achievements, and ideas make him a figure worthy of commemoration, but one of his most critical contributions was his argument that African Americans were not peripheral to the American story but instead at the very heart of it. Woodson essentially attempted to completely reframe American history.

Ironically, a man so fully associated with education achieved his own educational milestones through a strikingly alternative path. Born to former slaves in Reconstruction-era Virginia, Woodson grew up in significant poverty and was unable to attend school for more than brief periods. After his family moved to West Virginia, he went to work as a coal miner at the age of 17, and was only able to enroll in Huntington’s Douglass High School (a segregated school named after Frederick Douglass) when he was 20 years old. But he graduated in two years, began teaching at a nearby school for the children of African American miners, and at the age of 25 was named Douglass High’s principal.

Woodson’s personal and professional links to education continued to develop from there in unconventional but groundbreaking ways. He took classes part-time at Kentucky’s Berea College while working at Douglass and received a BA in Literature in just three years. He then worked as a school supervisor in the Philippines for four years, returning to the United States (after a semester of study at the Sorbonne in Paris) to complete a second BA at the University of Chicago and then a PhD in History from Harvard (making him the second African American to receive a doctorate in history, after W.E.B. Du Bois). He would go on to work as a professor and dean at multiple historically black colleges and universities (HBCUs), including Howard University and the West Virginia Collegiate Institute.

Those academic achievements—a doctorate and then faculty and administrative roles in higher education—might seem far removed from, if not opposed to, Woodson’s partial and haphazard educational first steps. But in his own lifelong arguments about African American education Woodson instead sought to link these disparate worlds, in two distinct ways: First, the realities of segregated education in America meant that African Americans could only achieve educational success through such haphazard opportunities, and Woodson argued that the highest levels of individual educational attainment could nonetheless stem directly from and build upon those opportunities. Second, educators and activists like Woodson worked in this era to create vital, collective resources for all African American students, families, and communities, from preparatory schools like Douglass to HBCUs like Howard, among many others.

Woodson’s experiences of community also inspired another of his most influential efforts and legacies. During his time in Chicago he stayed at the Wabash Avenue YMCA, a longstanding institution in the city’s historic African American Bronzeville neighborhood. It was that community, Woodson would later detail, that inspired him in 1915 to create the Association for the Study of Negro Life and History, an organization devoted to better remembering and documenting such communities and their histories and stories. The Association (still in existence today as the Association for the Study of African American Life and History) published The Journal of Negro History and the Negro History Bulletin, worked with educators and schools around the country, and promoted the consistent and rigorous study of African American history both within and outside of the educational system.

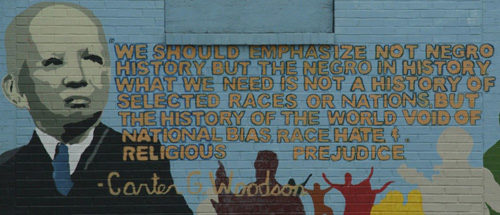

After founding the Association Woodson published his first two groundbreaking historical books, A Century of Negro Migration (1918) and The Education of the Negro Prior to 1861 (1919). He would go on to write and publish many more books over the next few decades, works that spanned academic disciplines, educational debates, and public conversations. But perhaps even more important than the works themselves was Woodson’s radical reframing of what African American history meant and should mean for American community and identity. As he succinctly put it in describing the central goal of Negro History Week, “We should emphasize not Negro history, but the Negro in history.”

That might seem like a small or semantic difference, but I believe it instead reflects a profound revision and reframing. African American history, Woodson consistently argued, was not separate from nor peripheral to American history—it was instead at the heart of it, a crucial thread without which the larger fabric would not hold together (if it would still exist at all). That argument focused first and foremost on education, as Woodson noted that African Americans had for too long been “overlooked, ignored, and even suppressed by the writers of history textbooks and the teachers who use them.” But it was just as much a reframing of our collective memories, an effort to make African American history meaningful and vital for every American community and story.

There are many reasons we should feature Carter G. Woodson in our Black History Month commemorations this year, from his originating role and communal activisms to his inspiring individual story and achievements. But most of all he reminds us that Black history matters because it is American history.