This series by American studies professor Ben Railton explores the connections between America’s past and present.

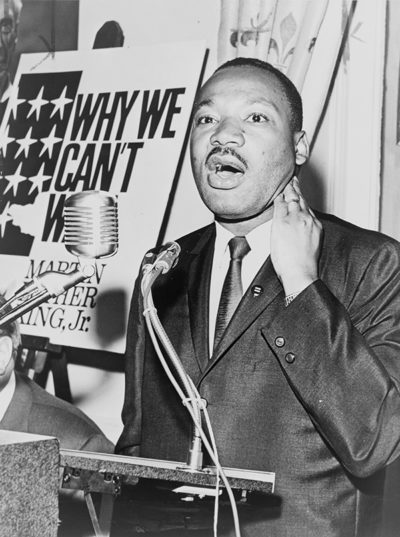

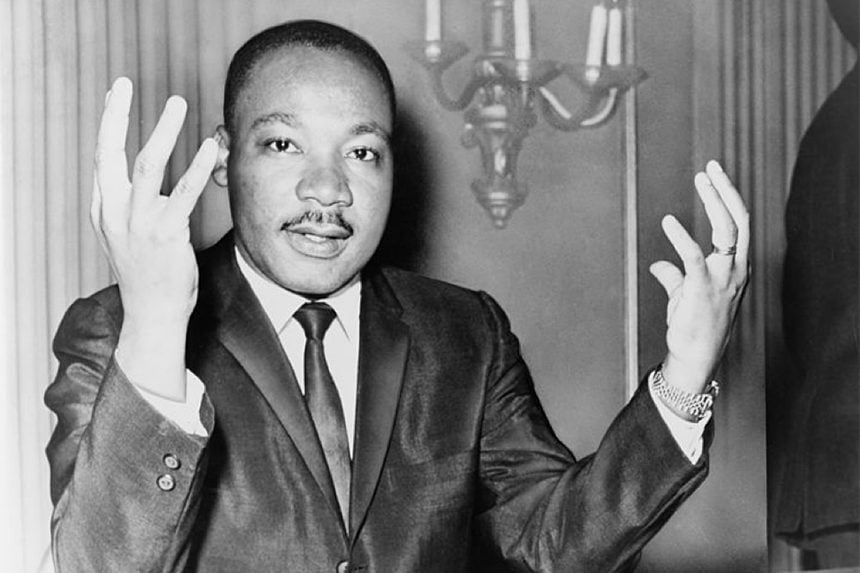

Over the half-century since his tragic assassination, Martin Luther King Jr. has gradually become one of those figures whose legacy is claimed on behalf of numerous positions and perspectives. Whatever the goals of those competing contemporary claims, it’s fair to say that any of them risks turning King and the Civil Rights Movement into images and icons rather than a multi-layered historical figures and events. The Martin Luther King Day holiday offers an important moment to step back from those trends and remember the histories themselves and the lessons they provide.

One of the most important such historical lessons is the central role of civil disobedience in King’s actions throughout the Civil Rights Movement. King’s emphasis on civil disobedience was inspired in part by his engagement with earlier models of that form of activism, including Henry David Thoreau’s war tax resistance and his essay “Resistance to Civil Government” (1849) and Mahatma Gandhi’s leadership of the movement for Indian independence.

But his emphasis on civil disobedience also locates King within the long tradition of African-American critical patriots. Critical patriotism as a concept challenges traditional definitions of patriotism as simply a celebration of the nation and support of the government.

Earlier this month, the tagline for a Washington Post article on the role of the journalist in times of war succinctly illustrated that narrative of traditional patriotism: “Are you a journalist first or an American first? With conflict looming, an old question about patriotism is raised anew.” In this vision, to be a patriotic American is to support the nation and express that support by participating in shared communal celebrations such as the national anthem and the Pledge of Allegiance.

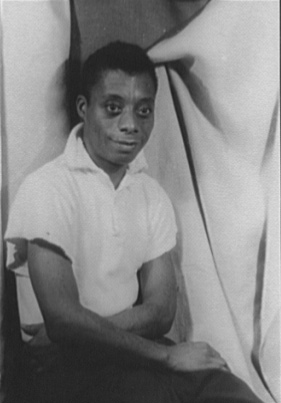

That celebratory form of patriotism is often associated with phrases like “Love it or leave it,” with the idea that if one does not share such a perspective, one is both unpatriotic and undeserving of being part of the national community. But in a striking quote from his essay collection Notes of a Native Son (1955), James Baldwin, King’s contemporary and one of the era’s most eloquent and vital literary and cultural voices, models a contrasting vision of both the love of one’s country and patriotism. “I love America more than any other country in the world,” Baldwin writes, “and, exactly for this reason, I insist on the right to criticize her perpetually.”

That critical form of patriotism has been exemplified by many figures throughout American history, but African Americans have a particularly rich legacy of critical patriotism. “It is black people who have been the perfecters of this democracy,” argues journalist Nikole Hannah-Jones in the introductory essay for the 1619 Project, the August 2019 New York Times Magazine public scholarly work she initiated and directed. Seen through this lens, for example, histories of slave resistance and revolt comprise not just quests for individual and collective freedom, but efforts both to force the nation to grapple with its failings and to move it closer toward its ideals of “liberty and justice for all.”

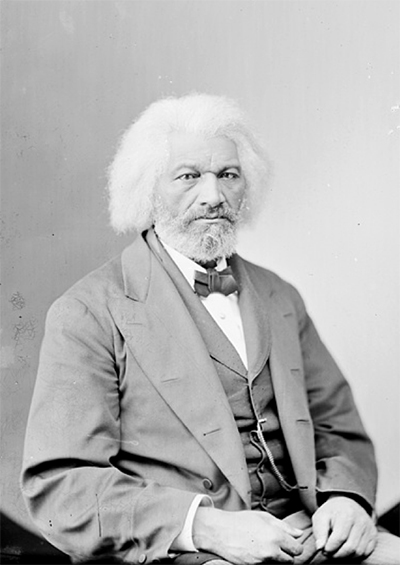

One of the most influential voices of critical patriotism, Frederick Douglass, modeled those efforts in his speech “What to the Slave is the 4th of July?” (1852). Invited to speak at a Rochester, New York celebration of that holiday, Douglass offers instead a potent critique of that occasion:

Fellow-citizens, pardon me, allow me to ask, why am I called upon to speak here today? What have I, or those I represent, to do with your national independence? Are the great principles of political freedom and of natural justice, embodied in that Declaration of Independence, extended to us? … This Fourth of July is yours, not mine. You may rejoice, I must mourn. (Douglass’ emphasis).

Douglass goes further, arguing that it is precisely such critique which is required:

At a time like this, scorching irony, not convincing argument, is needed. O! had I the ability, and could I reach the nation’s ear, I would, today, pour out a fiery stream of biting ridicule, blasting reproach, withering sarcasm, and stern rebuke. For it is not light that is needed, but fire; it is not the gentle shower, but thunder. We need the storm, the whirlwind, and the earthquake. The feeling of the nation must be quickened; the conscience of the nation must be roused; the propriety of the nation must be startled; the hypocrisy of the nation must be exposed; and its crimes against God and man must be proclaimed and denounced.

And he ends by making clear his patriotic purpose:

Allow me to say, in conclusion, notwithstanding the dark picture I have this day presented of the state of the nation, I do not despair of this country…I, therefore, leave off where I began, with hope.

The 1619 Project levies its own critiques of 1776 and our celebration of the Revolution, and as a result has become in recent months the subject of extended critiques in its own right, including attacks that have labeled it “unpatriotic” and “anti-American.” But like Douglass, King, and so many others, the Project expresses the two interconnected layers to critical patriotism:

- highlighting the manifold historical moments in which the nation has failed to live up to those ideals

- remembering and carrying forward the work of the figures and communities that have challenged those shortcomings and sought to move the nation closer toward the “more perfect union” envisioned in the Constitution’s Preamble

Another contemporary figure who has been frequently labeled as unpatriotic is Colin Kaepernick. In an August 2016 ESPN piece published shortly after Kaepernick began his controversial national anthem protests, his fellow NFL quarterback Drew Brees argued, “I disagree. I wholeheartedly disagree…it’s an oxymoron that you’re sitting down, disrespecting that flag that has given you the freedom to speak out.” Brees’s comments concisely illustrate how many Americans equate patriotism with demonstrating “respect for the flag” (and often, in critiques of Kaepernick, “support for the troops”) by participating fully and unequivocally in communal celebrations like standing for the national anthem.

Yet Kaepernick chose to kneel after consulting with former NFL player and Green Beret Nate Boyer over what form of protest would be most respectful to American veterans and servicemen and women. And in his public statements he linked that protest to both layers of a critically patriotic perspective mentioned above: highlighting the nation’s shortcomings (“That’s something that this country stands for: freedom, liberty, justice for all. And it’s not happening for all right now”); and seeking to move the nation closer to its ideals (“To me this is something that has to change and when there’s significant change and I feel like that flag represents what it’s supposed to represent in this country, is representing the way that it’s supposed to, I’ll stand”).

Kaepernick’s protest, like the 1619 Project, are open to response and debate. But labeling such efforts as unpatriotic reveals a limiting vision of patriotism as simply and solely the celebratory form. On Martin Luther King Jr. Day, let’s remember an alternate, critical form of American patriotism, one carried forward by both King and these contemporary voices.

Featured image: Martin Luther King Jr. (Library of Congress)

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

Thank you Professor Railton, and your additional words of wisdom. We always have to strive to do all we can, even if it seems like it’s against all odds, to help the U.S. reach it’s full potential no matter what.

As an 83 year old White male having lived through WWII, Korea, Vietnam and now Iraq, Afghanistan and perhaps Iran in the near future, as well as other wars the United States has either started or been involved in I applaud the actions of Colin Kaepernick. Frederick Douglass’s speech should be required reading in every high school in the country. The bitterness between the races in this country is not improving. We need leadership from someone (perhaps another Dr. Martin Luther King) or we could very well see the country divide and fall. (A house divided cannot stand). I look forward to hearing about Mr. Railton’s book and will be inline for one of the first copies.

Thanks for your comment and thoughts as ever, Bob.

I hear you and can’t dispute any of those diagnoses of America in 2020. But in terms of our own engagement with our moment and society, to quote another wise figure, Gandalf: “So do all who live to see such times [wish they weren’t happening]. But that is not for them to decide. All they have to decide is what to do with the time that is given them.”

Doing what I can!

Ben

I read this well written article on American patriotism (and some of the helpful links). There’s much more here than Dr. King and what he accomplished during his 39 years. I think of what he could have accomplished had he not been assassinated, quite possibly still living to this day.

We’ll never know the good he would have accomplished from 1968 to the present. This nation certainly would have been all to the better for it had his voice of reason never been broken, becoming a historical figure (with diminished impact) many decades too early.

Partially because OF his death at that time, this country now is SUCH a divided mess in every way imaginable. Even he would be understandably overwhelmed as to what to do or where to start. If he were to attempt to give a speech today, he’d be drowned out by infighting in the crowd, brawls, riots, likely shootings and more. He’d be dealing with a nation and culture on the level of ‘The Joker’ film, and complete chaos in the highest levels of the government just for starters. It would be like a fireman attempting to save a home completely engulfed in flames.

Other than the physicality of places and things, Dr. King would find the U.S. unrecognizable and his hands tied behind his back for all intents and purposes.

PS. Just wanted to note that the history of competing American patriotisms is the subject of the book I’m writing this spring, so even more than usual (which is a lot!) I’m interested in responses and thoughts on this column. Thanks, all!

Ben