Guide to the Archive: Agatha Christie

In the 1930s and ’40s, Agatha Christie’s work appeared frequently in The Saturday Evening Post.

Way back in 1933, the Post introduced her Belgian detective, Hercules Poirot, to America. Altogether Christie’s cerebral sleuth appeared in six Post issues during the 1930s. The Post also published six other mysteries by Christie, including “Endless Night,” a lesser known work that she included among her five favorite books.

Stories by Agatha Christie

“Murder in the Calais Coach, Part 1,” September 30, 1933, page 5

“Murder in the Calais Coach, Part 2,” October 7, 1933, page 20

“Murder in the Calais Coach, Part 3,” October 14, 1933, page 18

“Murder in the Calais Coach, Part 4,” October 21, 1933, page 20

“Murder in the Calais Coach, Part 5,” October 28, 1933, page 26

“Murder in the Calais Coach, Part 6,” November 4, 1933, page 26

“Murder in Three Acts, Part 1,” June 9, 1934, page 5

“Murder in Three Acts, Part 2,” June 16, 1934, page 20

“Murder in Three Acts, Part 3,” June 23, 1934, page 20

“Murder in Three Acts, Part 4,” June 30, 1934, page 20

“Murder in Three Acts, Part 5,” July 7, 1934, page 20

“Murder in Three Acts, Part 6,” July 14, 1934, page 26

“Death in the Air,” Part 1,” February 9, 1935, page 5

“Death in the Air,” Part 2,” February 16, 1935, page 20

“Death in the Air,” Part 3,” February 23, 1935, page 20

“Death in the Air,” Part 4,” March 2, 1935, page 26

“Death in the Air,” Part 5,” March 9, 1935, page 26

“Death in the Air,” Part 6,” March 16, 1935, page 24

“Murder in Mesopotamia, Part 1,” November 9, 1935, page 5

“Murder in Mesopotamia, Part 2,” November 16, 1935, page 20

“Murder in Mesopotamia, Part 3,” November 23, 1935, page 20

“Murder in Mesopotamia, Part 4,” November 30, 1935, page 20

“Murder in Mesopotamia, Part 5,” December 7, 1935, page 28

“Murder in Mesopotamia, Part 6,” December 14, 1935, page 28

“Cards on the Table, Part 1,” May 2, 1936, page 5

“Cards on the Table, Part 2,” May 9, 1936, page 22

“Cards on the Table, Part 3,” May 16, 1936, page 24

“Cards on the Table, Part 4,” May 23, 1936, page 24

“Cards on the Table, Part 5,” May 30, 1936, page 26

“Cards on the Table, Part 6,” June 6, 1936, page 28

“Poirot Loses a Client, Part 1,” November 7, 1936, page 5

“Poirot Loses a Client, Part 2,” November 14, 1936, page 24

“Poirot Loses a Client, Part 3,” November 21, 1936, page 24

“Poirot Loses a Client, Part 4,” November 28, 1936, page 20

“Poirot Loses a Client, Part 5,” December 5, 1936, page 20

“Poirot Loses a Client, Part 6,” December 12, 1936, page 20

“Poirot Loses a Client, Part 7,” December 19, 1936, page 31

“Death on the Nile, Part 1,” May 15, 1937, page 5

“Death on the Nile, Part 2,” May 22, 1937, page 22

“Death on the Nile, Part 3,” May 29, 1937, page 22

“Death on the Nile, Part 4,” June 5, 1937, page 28

“Death on the Nile, Part 5,” June 12, 1937, page 26

“Death on the Nile, Part 6,” June 19, 1937, page 26

“Death on the Nile, Part 7,” June 26, 1937, page 27

“Death on the Nile, Part 8,” July 3, 1937, page 27

“The Dream,” October 23, 1937, page 8

“Easy to Kill, Part 1,” November 19, 1938, page 5

“Easy to Kill, Part 2,” November 26, 1938, page 20

“Easy to Kill, Part 3,” December 3, 1938, page 20

“Easy to Kill, Part 4,” December 10, 1938, page 27

“Easy to Kill, Part 5,” December 17, 1938, page 26

“Easy to Kill, Part 6,” December 24, 1938, page 20

“Easy to Kill, Part 7,” December 31, 1938, page 38

“—And Then There Were None, Part 1,” May 20, 1939, page 5

“—And Then There Were None, Part 2,” May 27, 1939, page 18

“—And Then There Were None, Part 3,” June 3, 1939, page 27

“—And Then There Were None, Part 4,” June 10, 1939, page 29

“—And Then There Were None, Part 5,” June 17, 1939, page 27

“—And Then There Were None, Part 6,” June 24, 1939, page 26

“—And Then There Were None, Part 7,” July 1, 1939, page 26

“The Body in the Library, Part 1,” May 10, 1941, page 9

“The Body in the Library, Part 2,” May 17, 1941, page 22

“The Body in the Library, Part 3,” May 24, 1941, page 26

“The Body in the Library, Part 4,” May 31, 1941, page 24

“The Body in the Library, Part 5,” June 7, 1941, page 26

“The Body in the Library, Part 6,” June 14, 1941, page 30

“The Body in the Library, Part 7,” June 21, 1941, page 30

“Remembered Death, Part 1,” July 15, 1944, page 9

“Remembered Death, Part 2,” July 22, 1944, page 28

“Remembered Death, Part 3,” July 29, 1944, page 28

“Remembered Death, Part 4,” August 3, 1944, page 32

“Remembered Death, Part 5,” August 12, 1944, page 32

“Remembered Death, Part 6,” August 19, 1944, page 32

“Remembered Death, Part 7,” August 26, 1944, page 32

“Remembered Death, Part 8,” September 2, 1944, page 32

“Endless Night, Part 1” February 24, 1968, page 59

“Endless Night, Part 2,” March 9, 1968, page 50

Video Image Credits

:07 Agatha Christie (National Archives, The Netherlands, CC0)

:17 Albert Finney Hercule Poirot: Alamy

:27 Murder on the Orient Express Promotional Photo: Alamy

:31 Lindbergh Kidnapping Poster (Wikimedia Commons. Published in the United States between 1924 and 1977 without a copyright notice.)

:55 David Suchet Hercule Poirot: Alamy

:59 Kenneth Branagh Hercule Poirot: Alamy

1:18 Endless Night Movie Photograph: Alamy

1:22 Endless Night Movie Photograph Funeral: Alamy

1:43 Ray Bradbury Photo (Wikimedia Commons. Published in the United States between 1924 and 1977 inclusive, without copyright notice.)

1:45 F. Scott Fitzgerald Photo (Wikimedia Commons. Publication occurred prior to January 1, 1924)

1:46 Dorothy Parker Photo (Wikimedia Commons. This image is available from the United States Library of Congress‘s Prints and Photographs division under the digital ID ggbain.05631)

Featured image: Illustration by Rubin, ©SEPS

Agatha Christie’s Two Unsolved Mysteries

The unexpected success of The Mousetrap is perhaps the one mystery in Agatha Christie’s works that she never solved.

When it opened in London on November 25, 1952, she told the play’s producer she expected it would run for just “eight months, perhaps,” before closing. Sixty-five years later, it is still being performed. Since 1974, it has continually appeared at London’s St. Martin’s Theatre, which make it the longest continuous run of any play. Ms. Christie was completely baffled by the play’s enduring appeal. In her autobiography, she wrote, “I had no feeling whatsoever that I had a great success on my hands, or anything remotely resembling that.”

It wasn’t the only unsolved mystery in her life.

In 1926, she left her husband and seven-year-old daughter and inexplicably disappeared without a trace. The story was recounted in The Saturday Evening Post in 1941.

Mystery Writer, Mystery Woman

All of the name is Agatha Mary Clarissa Miller Christie Mallowan. Somebody once said that she has made more money out of murder than any other woman since Lucrezia Borgia. She has done it by keeping all of her crimes on paper.

Although a large part of the English-speaking world has read one or more of Agatha Christie’s many mysteries at one time or another, very few people know much about her—and this is an age when the public usually knows all about its celebrities.

In fact, Mrs. Christie is something of a mystery woman. Even her agent and her publisher can supply little information about her.

Her manuscripts arrive without any of the explanations and interpretations in which most authors indulge, they’re published, they’re successful — some more than others. That’s about the net of it.

But (to point a paradox of the variety you’ll find in so many of her own murder mysteries) Mrs. Christie has in her time received an enormous amount of publicity. And (to pile paradox on paradox, again in murder-mystery fashion) the event which caused the spotlight of public attention to blaze upon her was itself a most baffling mystery— one in which she personally was the flesh-and-blood principal character.

This real mystery began on the wintry Surrey Downs of England where Mrs. Christie was living with her husband, Col. Archibald Christie, in 1926.

Shortly after dinner on a black December night she decided to motor alone across the Downs and do some thinking, something not unusual for a writer pondering plot complications.

Next morning Mrs. Christie’s abandoned car was found beside a hedge not far from a lonely stone quarry in the neighborhood. She had vanished without a trace.

The disappearance captured the imagination of the public in astonishing fashion, not only in England but throughout the world. Newspaper headlines from South Africa to Alaska front-paged the story day by day. Some of the news stories were on the cynical side, intimating that the disappearance was a publicity stunt because one of the Agatha Christie mysteries was running serially at the time.

One newspaper quoted Colonel Christie as saying that he thought his wife might have vanished during a sort of research experiment in her craft, because she often had expressed the belief that any inventive individual could disappear with complete success without much difficulty. A few friends supported this theory by relating how for years Mrs. Christie had been a very close student of the New York disappearance of Dorothy Arnold, reading everything published on the subject.

(Dorothy Arnold, the smartly dressed daughter of a wealthy family, left her parents’ home at 108 East Seventy-ninth Street, New York City, on December 12, 1910, after telling her mother she intended to do some shopping. She bought a box of candy at the Fifty-ninth Street store of Park and Tilford, and a copy of a book, Engaged Girl Sketches, at Brentano’s Fifth Avenue store. She’s never been traced from there to this day, despite thousands of false alarms down the years.)

The police took nothing for granted in the disappearance of Agatha Christie. In some swampland not far from her Surrey home was The Silent Pool, a bit of dark water covered by bracken and dead grass. It had been the scene of the death of one of the characters in a recent Christie mystery. Detectives dragged it again and again, thinking they might find the author’s body.

The theory that Mrs. Christie, a famous mystery writer, had disappeared to prove it could be done, intrigued the public. As the story grew into a seven-day wonder, search parties were organized throughout the British Isles, and hundreds of amateur detectives took up the quest. Society people joined in, in treasure-hunt fashion. Thousands of pounds were spent on the various hunts undertaken.

Eleven days after her disappearance, Mrs. Christie was traced to a Harrogate hotel through a note she had written. She’d been living there the entire time under the name of Nancy Neele, a woman she and her husband knew. She’d told stories of coming from South Africa, she appeared to have a great deal of money for shopping and entertaining, and the other residents of the hotel had considered her a gay and attractive recruit to their social circle.

At this point the newspapers began emphasizing their publicity-stunt suspicions with new vigor. Colonel Christie, a World War hero, seemed outraged. He retained two noted alienists, who examined Mrs. Christie and staked their professional reputations on the diagnosis that she had suffered a genuine loss of memory.

A little over a year later Mrs. Christie divorced her husband under English law. Subsequently he married the woman whose name Mrs. Christie had used at the Harrogate hotel. On a visit to Scotland still later, Mrs. Christie met Max Edgar Lucien Mallowan, the British archaeologist especially noted for excavating Ur of the Chaldees. They were married in 1930 and thereafter Mrs. Mallowan accompanied her husband on expeditions to the Near East, his special field. The trips served to supply background for her writing.

Although she was born abroad, Mrs. Christie’s father was a New Yorker, the late Frederick Miller. As a girl she was shy, unable to make conversation at parties, and more interested in reading than anything else. Poetry and serious novels in which most of the characters died constituted her first attempts at writing. For a time the press described her as “an American novelist.” She tried a detective story, for fun, and it clicked immediately with the British reading public.

Today Mrs. Christie is doing war work for England, as is her husband. Information about the details of what they are doing is not available.

What the Post account doesn’t mention is that Colonel Christie was having an affair with the real Nancy Neele, and had indicated he wished to obtain a divorce.

Agatha Christie had a long relationship with The Saturday Evening Post. In 1933, we serialized her Murder in the Calais Coach, which introduced Post readers to her fictional master detective Hercules Poirot. Her Post debut was followed over the next thirty years by nine more novels and three short stories.

Christie’s never explained her disappearance. It has been variously explained as a psychogenic trance or a bout of amnesia. Or perhaps she was tired of her husband’s philandering ways and decided to take a break. In a departure from her regular form, the mystery remains unsolved.

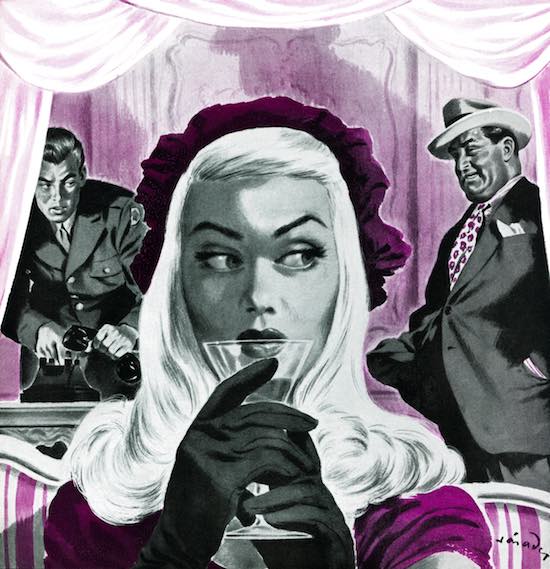

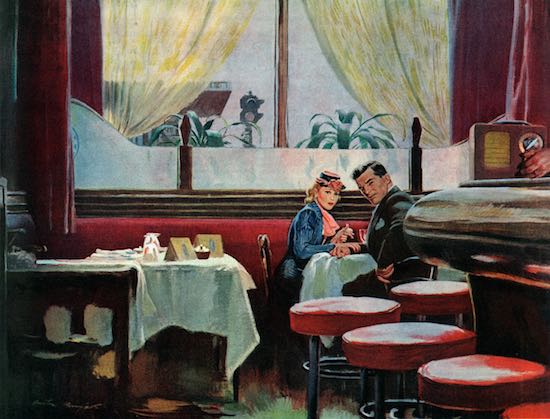

Gallery: Women of Mystery

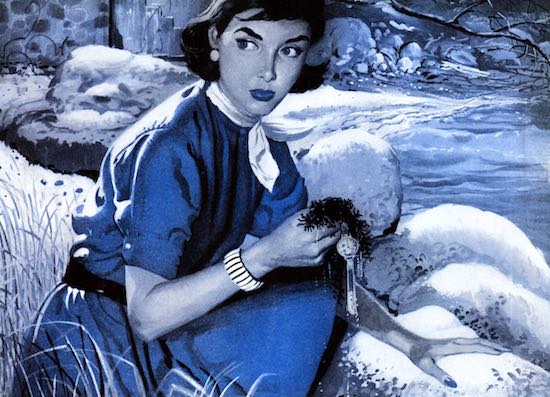

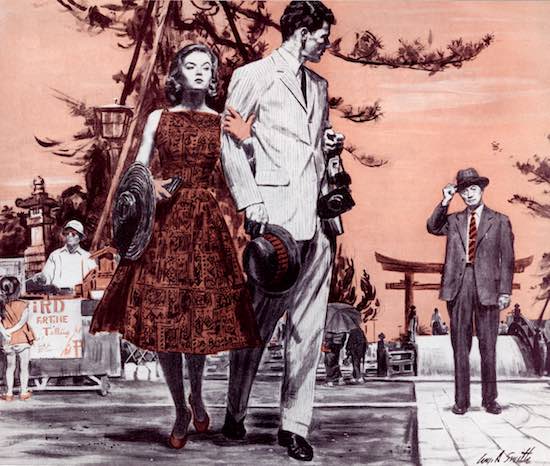

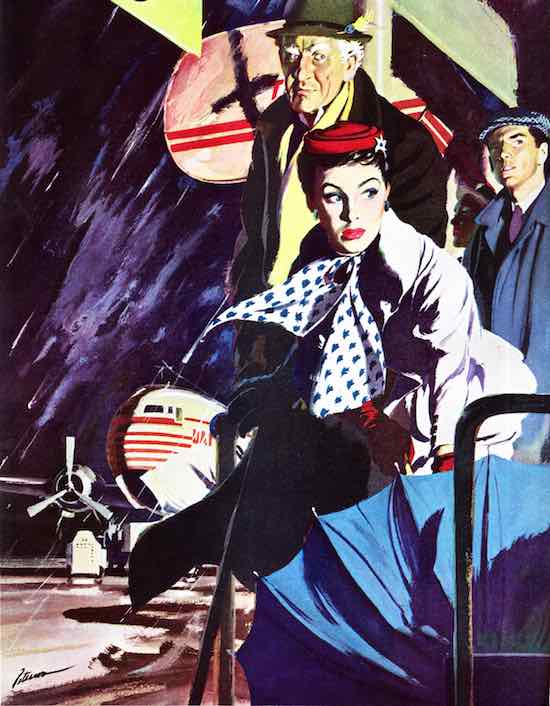

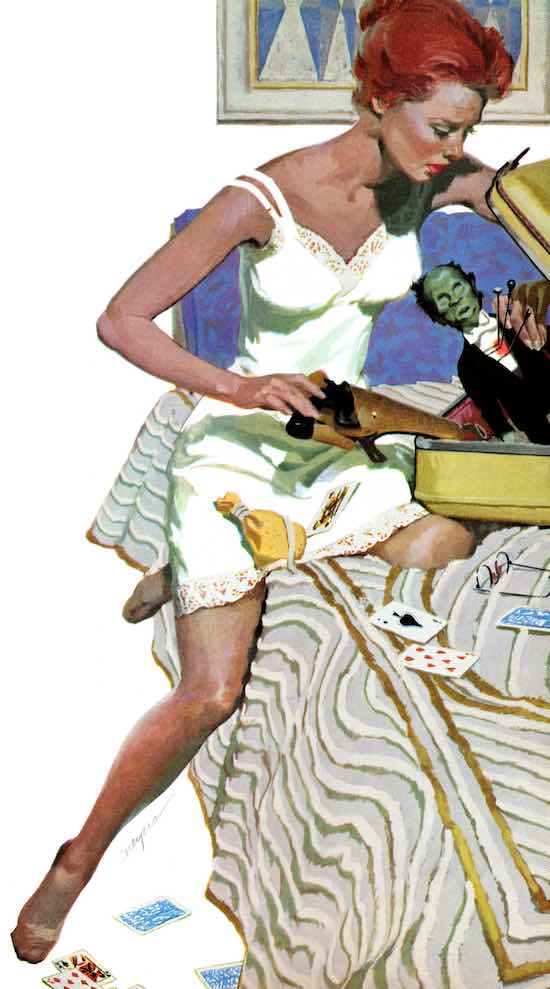

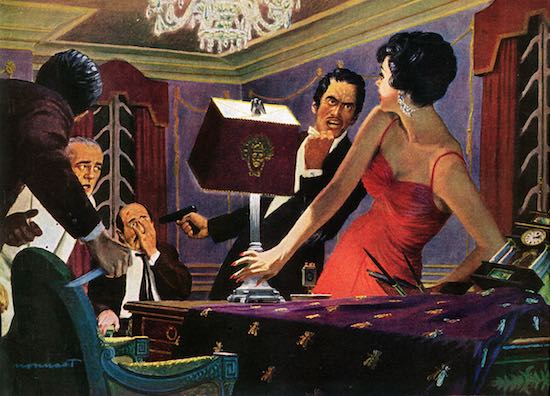

Whether the women in these 1950s-era illustrations are solving crimes or committing them, you can be sure there’s plenty of intrigue afoot!

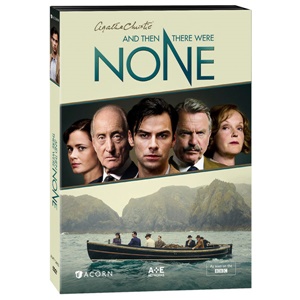

Which mystery-themed illustration do you like more? Let us know by responding with one of the designated emojis on our Facebook post! You’ll be entered into a random drawing for a chance to win a DVD set of Acorn TV‘s Agatha Christie’s And Then There Were None.

In And Then There Were None, Ten strangers meet in a solitary mansion on a remote island near the Devon coast. Awaiting the arrival of their hosts, they start to die, one by one. Based on the best-selling book by Agatha Christie, this lavish adaptation features an all-star cast including Aidan Turner (Poldark), Charles Dance (Game of Thrones), Toby Stephens (Vexed), Anna Maxwell Smith (The Bletchley Circle), Miranda Richardson (The Hours), and Sam Neill (Peaky Blinders). Seen on Lifetime.

Deadline to vote is January 23. See Official Rules.

The Outcasts

Peter Stevens

September 29, 1956

Furlough in Flatbush

Frederic Varady

August 19, 1944

The Unsuspected

Austin Briggs

August 11, 1945

Sentence of Death

Ken Riley

October 23, 1948

Easy to Murder

James R. Bingham

January 6, 1951

Girls Are Where You Find Them

George Englert

January 17, 1953

Death in the Wind

Bernard D’Andrea

November 5, 1955

Rendezvous in Tokyo

William A. Smith

December 15, 1956

Murder on Order

Perry Peterson

March 9, 1957

The Artless Heiress

Robert Meyers

June 1, 1957

Gem Thief

November 29, 1958

It All Happened to Me

Austin Briggs

July 1, 1950

Feminine Reflex

George Englert

September 3, 1949

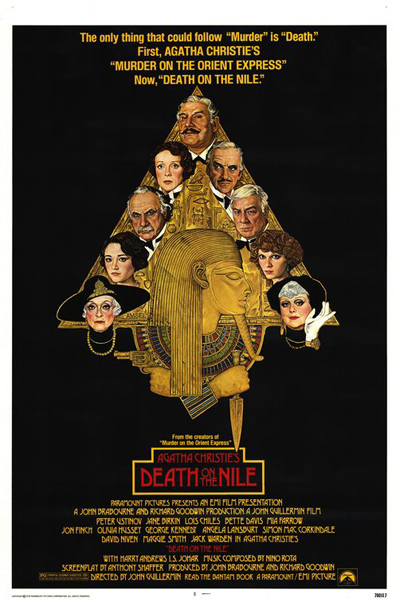

Death on the Nile (1978)

The Post first ran Agatha Christie’s “Death on the Nile” on May 13, 1937, and completed the series in eight parts. In 1978, John Guillermin directed the highly successful film adaptation starring Mia Farrow, Lois Chiles, Bette Davis, Angela Lansbury, Maggie Smith, and Peter Ustinov in the first of his six appearances as the deductive hero, Hercule Poirot. Cybill Shepherd was originally offered the role of the ill-fated Linnet Ridgeway but she turned it down.

To ensue the film’s authenticity and adherence to Christie’s storyline, it was shot on location in Egypt for seven weeks, four weeks entirely on a riverboat steamer. The mid-day heat often rose to more than 130 degrees, halting production until temperatures cooled off. Due to the size of the boat, no one was allowed to have their own dressing room, so all five leading actresses had to share a single room (how that went over, one can only speculate.)

The film was nominated for several awards, including a Golden Globe for Best Foreign Film (England), one BAFTA for Best Actor (Ustinov) and two for Best Supporting Actress (Lansbury and Smith), and it won an Oscar and a BAFTA for Best Costume Design.