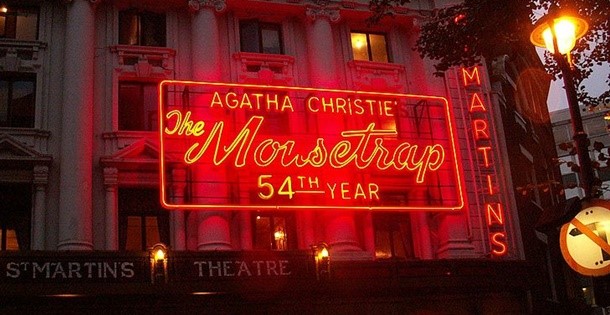

The unexpected success of The Mousetrap is perhaps the one mystery in Agatha Christie’s works that she never solved.

When it opened in London on November 25, 1952, she told the play’s producer she expected it would run for just “eight months, perhaps,” before closing. Sixty-five years later, it is still being performed. Since 1974, it has continually appeared at London’s St. Martin’s Theatre, which make it the longest continuous run of any play. Ms. Christie was completely baffled by the play’s enduring appeal. In her autobiography, she wrote, “I had no feeling whatsoever that I had a great success on my hands, or anything remotely resembling that.”

It wasn’t the only unsolved mystery in her life.

In 1926, she left her husband and seven-year-old daughter and inexplicably disappeared without a trace. The story was recounted in The Saturday Evening Post in 1941.

Mystery Writer, Mystery Woman

All of the name is Agatha Mary Clarissa Miller Christie Mallowan. Somebody once said that she has made more money out of murder than any other woman since Lucrezia Borgia. She has done it by keeping all of her crimes on paper.

Although a large part of the English-speaking world has read one or more of Agatha Christie’s many mysteries at one time or another, very few people know much about her—and this is an age when the public usually knows all about its celebrities.

In fact, Mrs. Christie is something of a mystery woman. Even her agent and her publisher can supply little information about her.

Her manuscripts arrive without any of the explanations and interpretations in which most authors indulge, they’re published, they’re successful — some more than others. That’s about the net of it.

But (to point a paradox of the variety you’ll find in so many of her own murder mysteries) Mrs. Christie has in her time received an enormous amount of publicity. And (to pile paradox on paradox, again in murder-mystery fashion) the event which caused the spotlight of public attention to blaze upon her was itself a most baffling mystery— one in which she personally was the flesh-and-blood principal character.

This real mystery began on the wintry Surrey Downs of England where Mrs. Christie was living with her husband, Col. Archibald Christie, in 1926.

Shortly after dinner on a black December night she decided to motor alone across the Downs and do some thinking, something not unusual for a writer pondering plot complications.

Next morning Mrs. Christie’s abandoned car was found beside a hedge not far from a lonely stone quarry in the neighborhood. She had vanished without a trace.

The disappearance captured the imagination of the public in astonishing fashion, not only in England but throughout the world. Newspaper headlines from South Africa to Alaska front-paged the story day by day. Some of the news stories were on the cynical side, intimating that the disappearance was a publicity stunt because one of the Agatha Christie mysteries was running serially at the time.

One newspaper quoted Colonel Christie as saying that he thought his wife might have vanished during a sort of research experiment in her craft, because she often had expressed the belief that any inventive individual could disappear with complete success without much difficulty. A few friends supported this theory by relating how for years Mrs. Christie had been a very close student of the New York disappearance of Dorothy Arnold, reading everything published on the subject.

(Dorothy Arnold, the smartly dressed daughter of a wealthy family, left her parents’ home at 108 East Seventy-ninth Street, New York City, on December 12, 1910, after telling her mother she intended to do some shopping. She bought a box of candy at the Fifty-ninth Street store of Park and Tilford, and a copy of a book, Engaged Girl Sketches, at Brentano’s Fifth Avenue store. She’s never been traced from there to this day, despite thousands of false alarms down the years.)

The police took nothing for granted in the disappearance of Agatha Christie. In some swampland not far from her Surrey home was The Silent Pool, a bit of dark water covered by bracken and dead grass. It had been the scene of the death of one of the characters in a recent Christie mystery. Detectives dragged it again and again, thinking they might find the author’s body.

The theory that Mrs. Christie, a famous mystery writer, had disappeared to prove it could be done, intrigued the public. As the story grew into a seven-day wonder, search parties were organized throughout the British Isles, and hundreds of amateur detectives took up the quest. Society people joined in, in treasure-hunt fashion. Thousands of pounds were spent on the various hunts undertaken.

Eleven days after her disappearance, Mrs. Christie was traced to a Harrogate hotel through a note she had written. She’d been living there the entire time under the name of Nancy Neele, a woman she and her husband knew. She’d told stories of coming from South Africa, she appeared to have a great deal of money for shopping and entertaining, and the other residents of the hotel had considered her a gay and attractive recruit to their social circle.

At this point the newspapers began emphasizing their publicity-stunt suspicions with new vigor. Colonel Christie, a World War hero, seemed outraged. He retained two noted alienists, who examined Mrs. Christie and staked their professional reputations on the diagnosis that she had suffered a genuine loss of memory.

A little over a year later Mrs. Christie divorced her husband under English law. Subsequently he married the woman whose name Mrs. Christie had used at the Harrogate hotel. On a visit to Scotland still later, Mrs. Christie met Max Edgar Lucien Mallowan, the British archaeologist especially noted for excavating Ur of the Chaldees. They were married in 1930 and thereafter Mrs. Mallowan accompanied her husband on expeditions to the Near East, his special field. The trips served to supply background for her writing.

Although she was born abroad, Mrs. Christie’s father was a New Yorker, the late Frederick Miller. As a girl she was shy, unable to make conversation at parties, and more interested in reading than anything else. Poetry and serious novels in which most of the characters died constituted her first attempts at writing. For a time the press described her as “an American novelist.” She tried a detective story, for fun, and it clicked immediately with the British reading public.

Today Mrs. Christie is doing war work for England, as is her husband. Information about the details of what they are doing is not available.

What the Post account doesn’t mention is that Colonel Christie was having an affair with the real Nancy Neele, and had indicated he wished to obtain a divorce.

Agatha Christie had a long relationship with The Saturday Evening Post. In 1933, we serialized her Murder in the Calais Coach, which introduced Post readers to her fictional master detective Hercules Poirot. Her Post debut was followed over the next thirty years by nine more novels and three short stories.

Christie’s never explained her disappearance. It has been variously explained as a psychogenic trance or a bout of amnesia. Or perhaps she was tired of her husband’s philandering ways and decided to take a break. In a departure from her regular form, the mystery remains unsolved.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

Many online articles are now dedicated to the disappearance of Agatha Christie. They are added to each other every year and none gives an answer to the mystery and this strange case remained unexplained because the question was: What happened at Newlands Corner during the night of December 3 to 4, 1926?

By the first part of 2019 I carried out a study, an online investigation on the subject ( inside disappearances in December cases). Then, since May 2019, I gave an answer to the “How”, and specify what happened with details.

The result is of course a speculation, but to which I bring points, facts, references found in the work of some Authors and those of Agatha Christie’s herself.

Bringing together the elements of the Puzzle we can now establish a new theory about the missing of the novelist in december 1926.

In any case I give all the details of the story between Sunningdale and London, an unpublished before proposal as answer, adding a realistic chronology of events, by six texts that can be summarized as “The Secret at Newlands Corner”.

Regards.