“Birthday” by Mildred Cram

American writer Mildred Cram was nominated for an Oscar for her part in writing the film Love Affair in 1939, and her 1920 story “Stranger Things” was a finalist for the O. Henry Award. Cram’s short story “Birthday,” published in 1928, captures a widow’s struggle to live it up on her fiftieth birthday.

Published on September 15, 1928

Bessie had never enjoyed her birthdays, but after Henry’s death she tried not to notice them. “Good Lord! It’s the twenty-third!” Mrs. Struthers, on the eleventh floor, reached sideways and snatched the telephone from the bed table. “Bessie? It’s the twenty-third — you’re fifty! Many happy returns.”

Bessie, on the ninth, tried to grin into the mouthpiece. “Sweet of you, dear, to call me.” Henry, at least, had made of this day a ceremony. He had never forgotten to send her flowers or a box of candy, and, toward the end, rubies. “Sweet of you to call me.”

“How does it feel to be fifty?”

Well, how did it feel to be fifty? Bessie Lovering lay for a long time in bed, trying to detect any differences in herself. She felt exactly as she had felt yesterday or a year ago — in fact, she was practically certain that no change had taken place in her for thirty years. At twenty she had crossed a line. She had married Henry Lovering. “I, Henry, take thee, Elizabeth.” The veil. The blossoms. The importance of being Mrs. Lovering. She was still Mrs. Lovering. Being a widow only made marriage more important.

She lifted the phone again. “Service? Please send breakfast to 969.”

“Yes, madame. The usual?”

“Have you any corn muffins?”

“Yes, madame… Very good, madame.”

“Plenty of cream for the coffee, George. Yesterday I had to send for more.”

“Certainly, madame. Anything else?”

“That’s all.”

She stretched herself, throwing back the soft coverlet, to disclose her body clad in crêpe de chine, with insets of real lace and knots of baby-blue ribbon. She had pretty feet and she had always taken care of them. She wiggled her toes and lifted one leg.

“I must exercise.”

One leg up! The other leg up! Deep breath! Relax! She sank again into the deep mattress. Funny how sleepy she was, how tired, when she never did anything to tire herself. She had not been tired in the days of Henry’s poverty, when she rose at six o’clock to get breakfast for him and the boys. She closed her eyes and recalled the alarm clock crashing into her dreams, shattering them, and the cold dark room, and Henry, in his bare feet, sitting on the edge of the bed, groaning “Gosh, mother, I hate to get up!” until she shook him awake.

Was Henry still objecting to getting up, wherever he was? Where was Henry? She must ask the swami. He seemed to have that faculty, apparently granted only to dark Hindu gentlemen in satin, turbans, of knowing what no one else even pretended to know. You had only to ask a Hindu “What is death?” and he had an answer — an authoritative if cryptic answer, smug, ready-made and patronizing. It had always puzzled Bessie that these matters — immortality, ghosts, transmigration, healing — were not written down somewhere so that all the sick, suffering, questioning world might read and understand. Why must they be kept secret or imparted in parables by contemptuous Hindu gentlemen to eager American ladies with more money than wisdom?

Like everything else in life, it was slightly, vaguely disturbing. Better not think about it. When the time came to die she would probably take an express elevator to heaven and step out on a sort of roof garden overlooking the universe. Henry would be there, smoking and chatting with a lot of traveling men, and he would throw away his cigar to come toward her with his old line: “Well, Bessie, you’re ten minutes late.”

Ten years late, already! She wondered whether he would have forgotten her. There must be a lot of pretty women in heaven, and ten years is a long time. “I must exercise!” She was getting fat. Her legs were still good, but she had thickened through the middle. Her arms above the elbow were heavy. Pound by pound, ounce by ounce, through the greedy years she had filled out the lovely slim flanks of her and had surrendered her flexible waist to a certain rigidity, a look of being fixed within her stays. She no longer walked quite erect. Her garters pulled her forward a trifle and she had acquired the habit of looking down as once upon a time she had looked up, letting her pretty feet carry her where they would.

Nowadays she could not trust her feet, because they were much too small to bear her weight. She wore beautiful shoes, sheer hose, silk to the top, and it pleased her to watch their reflection in store windows or chance mirrors — her young legs.

“Breakfast, madame?”

“Oh, wait a minute! Wait a minute!” She struggled into a kimono. “All right, come in.”

As usual, she had her breakfast served on a table near the window. The hotel faced the bay. She could look out across the roofs of the city toward the ferry lanes, the fleet anchorage, and across the glittering water, to Berkeley and the hills. Straight down, nine stories, people walked in the square and strings of taxis moved up before the porte-cochère of the hotel. It was all very busy and purposeful and young. San Francisco was young. It was not a place to be old. It was a city for flappers and boys, roadsters, laughter, dancing, insouciant dreams and promises. Not a place for idleness like hers. And yet she loved it.

The very activity of the ferries delighted her — great shuttles crisscrossing back and forth, carrying people on endless, hopeful journeys across the bright water, in sunlight, beneath gay skies. She liked the fogs. She liked the steep, audacious streets, plunging down and leaping up, the screech of brakes, the patter of high-heeled slippers on asphalt set at acute angles. She liked the Orientals, the sailors, the flower venders. She was not a part of it, yet it animated her, kept her alive, made her aware of herself — her potential self that had never existed for Henry, that had been engulfed in poverty and postponement. Now, at fifty, she was rich and she was alone. Strange desires stirred in her — to be, for once, the Bessie who had never been.

“Nice day, madame.”

“It certainly is, George.”

“I brought madame a grapefruit.”

“Thanks…Oh, wait a second, George, till I get some change.”

“Yes, madame. Merci, madame.”

Mrs. Lovering spread the napkin across her knees and lifted covers, sniffing. Hot cakes, bacon, corn muffins. “I didn’t exercise. Well, tomorrow — ”

II

As she dressed she regarded herself with critical eyes. A fine skin. Henry had always said so. “A finer skin than yours,” he had said — “I’d like to see it. Show me Lillian Russell! Can’t hold a candle to you!”

She had always been told that she might be Lillian Russell’s twin sister. The resemblance flattered Bessie into pearls and a marcelled pompadour.

She saw now that her long, fine, silky yellow hair was old-fashioned. With a sudden breathlessness, as if she had plunged into cold water, she called the beauty parlor on the eleventh floor.

“Yes, please. . . A bob, a shampoo, a wave and a manicure. . . Mrs. Lovering. . . Ninth.”

There, in a gray-and-violet dressing room, beneath a shaded light and facing a mirror, she surrendered herself to a facile young man in a smock who held poised above her head the long scissors, the shears. She covered her face with her hands and a hot painful flush stained her cheeks.

“I don’t know!” she wailed. “Maybe I’m foolish. Maybe I’ll look a sight. Maybe I’m too old.”

Yvonne herself, in black satin, parted the curtains to look in upon the sacrifice.

“Too old, madame? One is never too old for the bob. Why, only yesterday I cut the hair of a great-grandmother! She said afterwards ‘Why didn’t I do it sooner?’ Honestly, Mrs. Lovering, you won’t regret it. Will she, Mr. Shaughnessy?”

“Positively not.”

The young man in the smock looked at Bessie in the mirror. His narrow, nervous fingers caught at the graying cascade of blond hair and lifted it, letting it fall again in a thin shower. He looked at her and yet did not look at her. There was an immense indifference in his eyes, an immeasurable weariness. It was the jaded disillusionment of the court barber, the initiated panderer to frivolity. Bessie would have preferred a Frenchman, a waxed flatterer who would have had at least the technic of deception. This young Irishman was too honest. He made her feel like a fool.

“Do her a short bob, Mr. Shaughnessy. Lift it here — so. Over the ears and back — so. A swirl. Just a little bang — ”

“Oh, no, not a bang! I look ridiculous in a bang.”

“Well, just a little spit curl. Madame’s forehead is high. You will see. You must have a permanent.”

“Not a permanent! My hair’s always been naturally curly.”

“To cut the hair reduces the curl. I will give you a permanent that will delight you–a big, soft, natural wave. Very fashionable just now in Paris — so — a swirl. So — Go ahead, Mr. Shaughnessy. I’ll come back.”

Yvonne was the last hold on sanity, on safety. The bright cold shears fell through Bessie’s hair — Bessie’s precious blond curls. Away. Away. Snip. Snip. A petal here, a petal there, as one strips a flower. There emerged the tearstained small face, the queer, round, denuded head of a stranger, the head of a blond rat.

“You ain’t crying? Say, that’s foolish. Crying won’t do any good.”

Mr. Shaughnessy pushed her head forward with strong fingers and attacked the nape of her neck. She felt the cold steel nipping there, biting off the little curls that Henry had called her love locks.

“What would the boys say?” she gasped.

“You got children, have you?” the barber asked.

“Two sons. They’re in Oregon, in the lumber business.”

“They got any kids of their own?”

“No,” she said. Thank God, she wasn’t a grandmother, shorn like this!”

“Say, I got a kid of my own!” Suddenly the scissors moved faster, with a furious industry and enthusiasm. “Born this morning at six o’clock. They let me see him. Say, maybe I didn’t run out to the hospital as soon as they phoned! The doctor was just leaving. He said everything was fine. So I went in and the nurse showed me the baby. Say! A girl! Not red, like most of them, but white, like — like a white rose. Not crying or anything. The prettiest mouth — ”

“Aren’t you getting it a little too short?”

“Eh?”

“My hair.”

“Say, maybe I am. You don’t have a baby every day in the week, do you? It’s no wonder I’m nervous. My wife’s only eighteen. Molly her name is. She was just over from the old country when I met her — didn’t know a thing. Now she’s the best little American you could hope to find… Turn your head a little. Did you want this wind-blown?”

“Wind-blown?”

“Say! Yvonne!”

Yvonne’s black satin presence, her absent-minded enthusiasm, again dominated the mirror.

It was at the coiffeuse and not at herself that Bessie looked for confirmation of her fear. She saw the sly, amused and cruel smile she dreaded, an instant before it was erased, supplanted by flattery.

“You look ten years younger! Doesn’t she? Marie, come here! Joyce, come here at once! I want you to see Mrs. Lovering’s new haircut. Isn’t it charming?”

“Yes, awfully becoming, Mrs. Lovering.”

“Isn’t it youthful?”

Yvonne seized a comb and raked at the shorn locks deftly, combing them violently forward, then aside and back, curling with little pats and subtle twistings.

“You look like your own granddaughter. Look at yourself! Here, Joyce, give me a mirror. Now look! When you’re waved you won’t know yourself. Silly girl, you’ve been crying. Marie, Mrs. Lovering’s been crying! And she’s so sweet and pretty! Why, honestly, you look like Lillian Gish with this cut. Such small features. Here, I’ll wave you myself.”

Out of her great mercy, Yvonne wielded the irons. There emerged a series of neat undulations placed with such skill that Bessie’s blond hair resembled, in its perfection, a wig. She gazed upon herself at first with horror, as at an intimate stranger in a nightmare; then, slowly, she caught the fever of the place — it burned within her. The three young women, laboring with whispered words of encouragement, evoked a new image. She began to like this reflection. A facial, the stinging application of tonics, ice, lotions, more ice, removed the traces of her cowardly tears and gave to her flesh a glow and a firmness of youth. Her hands, buffed and tinted by an anemic child with shadowed eyes and scarlet, petulant mouth, had the luster and pointed elegance of the waxen hands of a show window dummy. Her rubies caught the fire and struck a sullen, dark envy in the shadowed eyes of the manicurist.

“You have pretty hands, madame. Nice cuticle. You ought to use our Pond Lily Cuticle Cream. It’s very nice.”

At last Bessie rose. Yvonne said: “You must come for a reset on Tuesday. Let me see — the total — just twenty-seven-fifty… Thank you…Good morning. You look wonderful!”

III

She lunched with Mrs. Struthers and Callie Frisbuth in the Green Room.

“Bessie Lovering, don’t tell me your hair’s bobbed!”

“It certainly is. And I wish I’d done it ten years ago.”

Mrs. Struthers was like a black rabbit nibbling at invisible lettuce leaves. In her quick dark eyes there was always the look of an impending criticism; she seemed, even when most affable, prepared to pounce. She implied now, by an ostentatious silence and the flicker of a smile at Callie Frisbuth, that she thought Bessie’s haircut ridiculous.

Callie Frisbuth said: “I think older women are more dignified with long hair. And after forty, goodness knows, there’s nothing much except dignity left for us women. It’s terrible, disgusting, the way youth rules the world.” She sighed. “I feel so out of it.”

“Well, I don’t,” Bessie said, flashing her rubies over the bread and butter plate. “I feel younger than ever. I’d like to go to the football game in Berke this afternoon, instead of playing bridge with a lot of old women.”

“Well, I must say we’re flattered!”

“I mean it. I’d like to dance. I’d like to sit up all night. Old lady? Pooh! I’m just beginning.”

“Maybe you’ll marry again,” Callie Frisbuth, who was not married, said, tightening her lips.

“Maybe I will.”

“I think,” Callie Frisbuth said, “a woman with children — grown children like yours — is happier a widow. Second husbands are seldom a success. I mean as stepfathers.”

“But I never see my children! They’re too busy and too ambitious to need me. They’ll be marrying soon and starting lives of their own — children of their own!”

“I thought you cared a great deal for Mr. Lovering,” Mrs. Struthers said.

“I did — I do. But Well, sometimes I’m lonely. Evenings — ”

“A lot of us are lonely evenings,” Mrs. Struthers snapped. “You’d better keep your head, Bessie. Just because you’re bobbed, you aren’t any younger. At fifty you’ve got to see things as they are.”

Things as they are!

Something had happened to Bessie Lovering. The bridge tables in Mrs. Taylor Smith’s house on Russian Hill seemed to be too close together; the rattle of women’s voices, excited, angry, hysterical, anxious, beat on the eardrums like a savage tom-tom. So many ample bosoms; so much navy-blue crêpe de chine; so many pearl earrings and chokers and fox neck pieces. Rich women, idle women; women in the forties, the fifties, the sixties.

Suddenly Bessie wanted to be away. She did not wait for tea. The prizes — embroidered squares never to be used as chair backs — were distributed. Little heart shaped caviar sandwiches, ovals of lettuce, elliptical cakes and mounds of quartered toast. Coffee in thin, cream-colored cups. Pistachio ice cream. “But I’m reducing!” “Just one!” “If you count your calories religiously, my dear — ” Whipped cream, cherry tarts, cheese straws, salted nuts. “I won’t eat a bite of dinner.” Chopped olives. Shortcake. “M-m-m — good — Now don’t you look! I’m going to take just a little piece.”

From the windows, Bessie could see the bay and the ferries. Suddenly, passionately, she wanted to be in the bright, crowded stadium, to see youth heaped up in great yelling pyramids — youth riotous, joyous, unaware. She wanted to plunge herself in sunlight and color and noise.

“I guess I’ll buy a dress.” She slipped out and into a taxi. Her cheeks were flushed. Her neck, where the fur piece fell away, seemed naked, stripped. She said “Downtown.” And putting up her hand, felt the unaccustomed shortness above her ears, the brittle, singed, clipped curls against her cheeks.

She craved the satisfaction of spending money. An evening dress — something to dance in. She danced well. Like most heavy blond women, she was light on her feet. She wondered whether Henry had learned the fox trot and the Charleston in heaven. Henry could one-step with the best of them. Once, to her amazement, he had mastered the bunny hug. Funny old Henry! Henry, whose money made it possible for her to be comfortable all the rest of her days — comfortable, safe and alone!

“Oh, Mrs. Lovering, I have the most lovely new model! Just made for you. I said, the minute it came in, There’s Mrs. Lovering’s dress!”

This shop catered to the hypothetical superiority of its clients — walnut and brown velvet, rose brocade and shaded lights, but no show cases, no price tags, no obvious barter.

The saleswoman, clad in fluttering ends of chiffon, slim, even, frankly, emaciated, trod the sacred velvet with the mincing, impeded grace imparted to the female gait by undernourishment and spike heels. She was pale; her gray eyes held a gentleness and a sad frustration. She was elegant and meticulously grammatical. Her manners, even at five o’clock of a confined and distressing day, were without flaw or strain.

Bessie said, “I want an evening dress and a wrap.”

“Ah, yes, at once. I have just the thing. Something simple but important. Miss Adams, will you model the little white gown for Mrs. Lovering?”

Bessie sighed and waited. She was conscious of a curious sense of defeat, perhaps a reaction from the excitement of the morning.

“You look tired, Miss Peters,” she said.

The saleswoman leaned against the mirrored wall; she put her hands against her back; she drooped. “I am. I’m awfully tired — awfully tired.”

“Why don’t you sit down?”

“We’re not allowed. But sometimes my back aches so — ” She smiled. “Life isn’t easy, is it?”

“How old are you?” Bessie said.

“Twenty-two. But I feel fifty.”

“Why don’t you get married?”

Miss Peters caught her breath. “I’d like to, but my fellow’s out of a job. He’s a newspaperman. He’s broke. And I got poppa to do for… Sometimes — I get so tired just waiting, Mrs. Lovering — ”

“I know.”

“Waiting for happiness, waiting for a home, waiting for children of my own.”

“But you’re young.”

“What good’s youth?” The pale girl flung her head back, straining her throat until the muscles showed, taut and tortured. “What good’s youth to any of us? We’re throwing it away, making slaves of ourselves.” She caught her breath. A look of terror, of extreme deprecation, came into her eyes.

“Oh, Mrs. Lovering, forgive me! I forgot myself… Ah, Miss Adams, the little white dress! Very chic. Very new. A model. So youthful. So distinguished. The little wrap too. Together, the price is — let me see — five hundred and sixty-three — reasonable, don’t you think?”

IV

Bessie shook her head. “It’s too much, Miss Peters. But I’ll take it. I have a very special — a very special engagement tonight.”

She imagined herself going to a dance. The idea, conceived out of her great need, assumed an astonishing reality. She plunged into an orgy of buying — underwear, stockings, a little beaded bag, a frothy handkerchief, a necklace of crystal, a flower of transparent gauze, exotic and perishable.

Miss Peters ran back and forth on stilted heels. The party, Bessie’s very special engagement, animated the pale girl. She imaged a beautiful ballroom, people moving across a polished floor, music, flowers, happiness. Her cheeks flamed with excitement. She spread the flimsy lengths of chiffon and lace for Bessie’s inspection, but, in her heart, she herself was going to wear them. She saw herself in the arms of her lover, whirling gracefully, slowly, to the languid measures of a waltz, her cheek close to his, his dark head bent to hers, whispering, “I love you. I love you.” Their feet reflected in the polished floor. Chandeliers ablaze with light. Mirrors. Laughter. Roses. The fullness of heart that is realization.

Bessie, too, saw herself arrayed for happiness. Yet, by a curious reversal, she wore in the confusion of dream and fact the gown of another period — she saw herself in the full satin skirt, the tight bodice, the great, flaring sleeves of yesterday, pompadour, a sheaf of American Beauties, long kid gloves, a train; and Henry, baggy, shining, gentle, waiting at the foot of the stairs.

“Well, Bessie, ten minutes late!”

“Ten years late!”

“Beg pardon, madame?”

“I was thinking out loud.”

She stuffed herself and her packages into a taxicab. Already the streets were dark. The shops were closing. Cable cars were incrusted with people.

The lobby, when she crossed it in the wake of a laden bell boy, was animated, crowded. The victorious collegians swept through in a wave of color and laughter to the dining rooms. Girls and girls and girls. Slim silk-clad legs, like the legs of colts. Hats worn on the back of the head, revealing bland foreheads and wide, brilliant eyes. White teeth. Smooth round chins. Fur jackets and brilliant silk handkerchiefs. The laughter of girls. The hope of girls. The inestimable, precious illusion of girls — thousands of girls…

The bell boy preceded Bessie down the carpeted corridor to her door. He bristled with boxes and packages. He whistled softly. He was a nice boy, a polite boy, and Bessie fumbled in her bag for a tip.

“Put the bundles on the bed.”

“Yes, ma’am.” He obeyed with a flourish. “Shall I light the lights?”

“If you please.”

Already the loneliness, the silence of the room, made itself felt. Bessie turned with a shudder from the proofs of her extravagant folly.

“Going to the dance, Mrs. Lovering?”

“What dance?”

“The Stanford crowd’s here tonight. It’ll be a riot.”

“No,” she said, “I’m not going. I haven’t anyone to go with. I’m alone.”

The bell boy accepted her tip and pocketed it. Yet he hesitated.

“Say, Mrs. Lovering, if you’re alone — it’s like this: I’ve got a friend — a nice fellow, see? An Italian. His name’s Bellardi. He dances like a million dollars. He’d take you out, anywhere you’d like to go.”

“You mean I’d have to pay him?”

“Sure! It’s his business. He’s a good guy. Well-behaved, see? And a swell dancer. He knows the ropes. I could get him for you.”

Bessie’s hands trembled. “How much does he ask?”

“Twenty-five for the evening, and expenses.”

“He speaks English?”

“Sure! He was born in the Napa Valley. His father has a ranch out there. They’re wops. But you’d like him. No use your being alone Saturday night. Gee, it’s awful up here! What you need is a little life, see? I wouldn’t mention it, only I guess you’re lonely — I’ve noticed it. I said to myself often, Bellardi’d ought to take Mrs. Lovering out and show her the sights.’”

“He’s — he’s young?”

“Not too young — thirty. He’s a good guy and a grand dancer. You wait and see.”

Bessie glanced again at the parcels. Her flesh yearned toward adornment — to wear the white gown and the wrap and the flower!

“Very well,” she said briefly, “send him up at 8:30.”

The boy smiled. It was impossible to interpret the smile. Bessie was both disturbed and curiously gratified. She was partner in a conspiracy. She was, actually, engaged in a questionable undertaking. She was about to do an outrageous thing. She had stepped out of the impeding four walls of her respectability. The bell boy shared her secret. He smiled. She grew hot all over.

“I’ll be ready,” she said. She stopped him on the threshold. “And please don’t mention this to anyone. You understand?”

She turned to the boxes. She emptied them with hands that shook.

Seven o’clock! She ran into the formal stuffy sitting room and put it in order. Fresh flowers, thank heaven — Callie Frisbuth’s carnations and Mrs. Struthers’ roses. “On our dear Bessie’s fiftieth birthday, from her pals and fellow ancients, Callie and Evangeline.”

Back to the bedroom. A bath. Crystals. The pungent, aromatic sweetness of lavender and cologne. Her nice feet and legs. Her white flesh. Clouds of powder. Silk and lace. Tight satin stays. Cream. Lotion. Ice. Ouch! Cold! Powder. Rouge. Maybe a little eye pencil. Her funny hair.

She was going to a party! What would Henry say? She could take care of herself. Henry would say, “Go ahead and have a good time. You deserve it. You’ve been a good woman.”

She rang for the maid, but for some reason — perhaps the influx of victorious collegians — there was a delay. While she waited she scrutinized herself. She was almost beautiful. Something had come back into her face that had not been there for ten years — a look of expectancy.

“Yes, madame?”

“Will you help me with my dress?”

“Certainly, madame.”

This was a veritable wisp of a maid, a child in the uniform of servitude.

“I suppose you’re very busy tonight.”

“Yes, madame. I have the night duty. I’m on until two o’clock.”

Bessie ducked her shorn head and received the glittering white shift. It fell along her body like ice, clung heavily. The maid’s fingers touched the crystals lovingly; she fastened them about Bessie’s throat.

“Oh, lovely, madame!”

“Yes, aren’t they pretty?”

“And the flower?”

“Here on the shoulder.”

“You look very nice, madame.”

“Thank you. Will you powder my back and arms?”

“You have very nice skin, madame, for a woman of your age.”

Why did the girl have to say that? It wasn’t kind. She was cruel because she was young.

“Thank you, madame… Good night. I hope you have a very nice time.”

Bessie faced the mirror. She could not believe that this glittering creature was herself. When the telephone rang she shivered all over and her lips stiffened, grew momentarily cold.

“Mr. Bellardi to see Mrs. Lovering.”

“Send him up.”

She waited, fingering Mrs. Struthers’ roses. Her heart beat furiously. She thought: “I’m a fool. I’m a coward. I’m lost. What shall I say to him? How shall I pay him? Perhaps I’d better send him away.” She was frightened and exalted.

When the knock came at the door she could scarcely say “Come in!”

V

He proved to be not the dark overdressed dressed Italian she had fancied, but, rather, a neat, well-brushed young man, a sober young man. There was nothing racially characteristic about him save his black hair and eyes. He had the short straight nose, the quick smile of an Irishman.

“How do you do?” she said.

“Mrs. Lovering? My name is Bellardi. My friend Charlie sent me” He paused.

“I know. What arrangement — I mean, how do I pay you? Now or when we return?”

He smiled. “Well, it might be better now, if you don’t mind. I haven’t a cent.”

“Would fifty dollars — ”

He stepped brightly into the room. “That depends,” he said, “on what you want to do. Dinner? Theater? Some nice dance club? And then to the beach? Wine? Cabs? I should say seventy-five at least.”

“Very well, we’ll do everything. I’m in your hands.” She fumbled in the new beaded bag for the crisp price of her enjoyment. “My sons,” she said, “would be grateful — ” She could not go on.

“Sure. I’ll take good care of you. I never go where there’s anything rough. You trust me… Thanks.”

He pocketed the bills without glancing at them. He was neatly dressed; but he had no overcoat, and the gray informal hat he carried was old and faded. The bell boy had said that he was thirty years old; he looked younger. He had the fresh color, the strong white teeth of a boy of twenty.

“Your wrap?”

The formalities over, he became all at once the cavalier. With a flourish he placed the wrap upon Bessie’s shoulders. In the gesture there were both homage and grace without a trace of insincerity. He said nothing, but in his glance, as he held the door for her, there was admiration, a look personal and appraising and strangely pleasant. It had been ten years since anyone had noticed Bessie Lovering herself. The last thing Henry had said to her was her last unsolicited compliment: “You’re a handsome woman, Bessie. When I’m gone don’t wear black. You look better in colors.”

The elevator, already crowded, paused for them, and Bessie squeezed in beside Evangeline Struthers and Callie Frisbuth. Their startled eyes flew from Bessie’s magnificence to the dark sleek head of her tall escort.

“Mrs. Struthers, Miss Frisbuth — Mr. Bellardi.”

“How d’you do?” they said.

Mrs. Struthers pinched Bessie’s arm. “Who is he? Who is he, Bessie?”

“We’re going to the opera,” Callie offered. “Martinelli in Aida. We have a box.”

“Won’t you come, Bessie? Won’t you and Mr. — and Mr. — I didn’t catch the name — won’t you join us?”

Bellardi gazed politely into Bessie’s eyes. He seemed to suggest that he preferred to be alone with her.

“No, thank you, darling,” Bessie’s voice lifted. “We’re going to dance.”

The door opened and she swept out, Bellardi at her elbow. Now for the first time she was a part of the animated crowd in the lobby, as if, by the simple alchemy of short hair and an escort, all the lonely years had been erased. She no longer envied the gazelle-like girls of the lobby; she loved them. She was one of them. She was going to dance. She was going to dance!

A cab slid along the curb, but Bellardi rejected it for a rakish machine whose driver signaled to them with the smirk of a self-conscious wrongdoer.

One of Bessie’s crisp bills changed hands and she found herself upon the velvet cushions of someone’s town car, gazing upon the city through immaculate plate glass. A transformed city — a city marvelously gay, mysterious, promising. All the faces glimpsed in passing wore the masks of revelry. The crowds dissolved and clustered, lively figures in a pageant, and the leap of traffic between lanes of light was strangely exciting, exhilarating, like a race in a carnival. Bessie glanced down at her frivolous silver feet, at her tinted hands, her rubies, never so darkly bright as now. She had forgotten Bellardi. It had seemed for a moment as if Henry rode beside her.

“May I smoke?”

“Of course.”

The young Italian produced a battered package of cheap cigarettes. He offered Bessie one.

“No, thanks, not now.”

Promptly he quenched his own.

“Where are we going?”

“To the opera. No? Martinelli in Aida. We will show your friends that we, too, can sit in a box.”

“But I haven’t had dinner!”

“We will have coffee there, and later dine properly. Leave all to me.”

She found herself upon the inadequate chair offered to patrons of the opera. Bellardi removed her wrap. He drew his chair forward to the rail, gazed down at the orchestra pit, where, in the sudden darkness, a twitter of sound arose. The opera had begun.

Bessie did not like music. It was apparent that Bellardi did. He put his chin in his clenched hands and remained immovable, entranced, hypnotized until the end. Save for a brief promenade, when he offered her a cup of weak coffee in a thick cup, he did not speak to Bessie.

“I like Verdi,” he said. “I am Italian. It is in my blood. I am starved for music. This is food for me. Beefsteak? Not when I can hear Martinelli sing! A big voice — that fellow. My father knew him, long ago, in Venice.”

When they left the opera house he seized Bessie’s arm. “I tell you what! In honor of Martinelli, we dine and dance at the Casa Veneziana. What do you say?”

The Casa Veneziana was a long way downtown. Another motor, commandeered at the point of a ten-dollar bill, swept through the tunnel, followed a strange boulevard, climbed a dizzy cobbled hill and left them before a doorway flanked by gilded barber poles. They entered upon a wave of sound, a frantic confusion of voices, music, whistles, laughter and the rattle of crockery. The head waiter, clad in white duck and tightly girdled, wore upon his glistening bald head a tasseled fisherman’s cap.

Bessie’s white sequins turned blue in the light of many purple arcs. For this was a Venetian grotto. A semicircle of tables surrounded a dance floor flooded with artificial moonlight. Gondoliers of many nationalities threaded the maze with trays and glasses. Spaghetti, borne aloft upon perspiring palms, left a trail of appetizing odor. Coffee splashed from kitchen to table. Minestrone. Ravioli. Fritto misto. Thick slices of dark bread. Romanello. Bessie felt faint with hunger.

She thought, following Bellardi through the noisy crowd, “This is life. I ought to like it. At least I’m not alone.”

She would have preferred a hotel, the discreet dance floor and shaded lights of some Rose Room or Crystal Hall.

She found herself at a table close to the stage, where an orchestra, seated within a vast funereal gondola, played Hallelujah.

“Shall we dance?”

Bellardi placed his hat upon the table — by way of identification perhaps. He said, “Keep your wrap. It isn’t safe to leave it.” And embracing her, he drew her out on the floor. Perhaps Aida had gone to his head. His eyes were bright. His mouth smiled. He had the look of a faun. And he could dance. He seemed to float across the floor, insinuating his way, surely, carelessly, expertly, between the jazzing couples. Bessie’s head had no idea what her feet were doing. She felt the pressure of his hand upon her back; he guided her with a gentle, firm touch, a command, a whole book of instructions. He moved without effort, holding his head high, smiling his smile of a faun — or was it the smile of a little boy who has just eaten a lollipop?

Colored lights swept the dance floor in rotation. Purple. Blue. Yellow. Green. Red. Purple. Blue. Faces, grinning or absorbed or ecstatic,appeared now blanched, now flushed, now a sickly green. Bodies pressed close. A kaleidoscopic whirl of people danced in Bessie’s eyes. Her feet were scuffed upon. Table after table was deserted for this mad revivalist music. Hallelujah! Hallelujah! Helps to shoo th’ blues away! Satan lies a-waitin’ and creatin’ sin and woe, woe, woe! Sing Hallelujah! Hallelujah!

She felt Bellardi’s smooth hard cheek against her own. He paused, hummed, swayed, began the intricate swishing steps of the Charleston. Bessie’s heart felt funny. “Either I’m hungry or I’m old.” The wheeling faces blurred, grew dim. “Please,” she said, “stop! I’m going to faint.”

VI

Bellardi fanned her with the menu card. “You’re hungry, that’s all. Have some water. The waiter’ll be here in a minute with some onion soup. Food’s what you need.”

“I haven’t danced for ten years.”

“You don’t say! You dance well too. You dance like a young girl. For a heavy woman, you’re light on your feet.”

“And you,” she said — “you dance like a professional.”

“I’m not,” he said quickly. “I’m a newspaperman out of a job.” Suddenly he leaned across the table, smiling a queer, crooked sort of smile. “The truth is, Mrs. Lovering, I’ve never done this before.”

“Done — what?”

“I’m not a hired dancing man — the sort of fellow they call a gigolo. Charlie put me up to this. He knew I was broke. When he sent for me I said no. I couldn’t picture myself hauling an old woman around and being paid for it. But he said you were different. He said you were a nice woman — just lonely. And I don’t blame you. Gosh! I understand. It must get terrible up in that hotel room, with nothing to do and nowhere to go.”

“It does,” she said.

Her heart was still now; it seemed not to beat at all. Only the nerves on the surface of her body quivered and jumped and the roof of her mouth was cold. There was pain behind her eyes. Too many people! Too much noise! Balloons popped and wooden sticks whacked. Paper streamers zinged and tangled. Shrieks of laughter collided with the shrill blasts of tin whistles. Three men in velvet jackets entered the spotlight and sang — Santa Lucia. No one listened. Soup. Cheese. Coffee. Smoke, stinging, acrid. A policeman, leaning against a barber pole, watched the crowd.

“I’m sorry,” Bessie said.

“I’m not.” Bellardi again offered her a cigarette from the tattered package. She shook her head. And again he quenched his own, as if rebuffed by her refusal. “I’m not. I’ve enjoyed it. Maybe, tomorrow, I’ll feel better… Aida! Say, that music cut clean into my heart and scooped out a lot of self-disgust! Maybe tomorrow I’ll get a job. And believe me I need it. I’m broke. I hate to take your money for this, but I’m hungry. That’s a fact. I won’t go to my father. He wants me to be a farmer. He thinks writers are sissies.”

“How old are you?”

“I’m twenty-three.”

“Twenty-three! I’ve got a son twenty-eight!”

He glanced at her with a quick dark look of sympathy. “It’s a shame you don’t live with him,” he said.

“He’s going to be married.”

“So am I. . . . Say, Mrs. Lovering, she’s a peach. You ought to see her. And bright? She’s a whiz. Only twenty-two, and already she’s the crack saleswoman at Magnow’s French Shop. Going to be a buyer. Takes care of her dad and a kid sister. Her name’s Peters — Lila Peters.”

Two and two were making four in Bessie’s mind. She said “Give me a cigarette, please.”

“Sure!”

He leaped, the match glowed. For the first time she tasted the thick bitter smoke. Tobacco flakes clung to her dry lips. But she persisted, because, in her mercy, she sensed this boy’s need and his hunger. Smoke poured through his nostrils. He tipped his head back, opened his mouth and let the fumes curl along his tongue.

“She and I ought to be doing this — dancing and hearing music. We’re wasting our youth. We’re missing everything.” Gosh! It doesn’t seem fair.” He leaned forward again, clasping his hands, the cigarette balanced between his lips. “You understand, don’t you? You’re a mother. I guess you loved your husband. Sometimes I think I’ll go crazy. Lying alone in my room, thinking about her lying alone in hers — and my heart crying out loud!” He grinned. “I sound like a Dago, don’t I? Well, I am. It’s in my blood. When I love, I love hard. Lila too. She’s getting thin. She can’t sleep. And if she knew I was doing this — ”

Bessie put out her hand and laid it briefly, firmly on his. “You’re my guest. I know Miss Peters. She sold me this dress. I paid eight hundred dollars for what I’ve got on.”

“Your guest?”

“I’m old enough to be your mother. I’m heart-hungry myself. And I’m not a Dago. I’m Boston Irish. My name was Bessie Calahan.”

She ground the cigarette out in a glass dish, forgetting to flash her rubies.

“Listen! Evangeline Struthers’ grandfather owned the first newspaper ever published in San Francisco. Her father owned two more. Her husband owned a whole chain of them, from Seattle to Mexico. I guess she can find a job for you if you want one.”

Before the look in his eyes — a stark look, somehow blinded and confused — she blinked and rose. “I want to go home, please — quick. Pay the waiter and don’t wait for change. I’m tired.”

VII

She left him in the lobby and took the elevator to the ninth, alone. The carpeted halls were dimly lighted and silent. Only the black skirt of the little maid flitted around a corner and disappeared.

“I’m tired — tired.”

She closed the door of her bedroom softly, as if upon a sleeping dream — a dream not to be awakened, a dream that must not be disturbed.

She kicked off the tight silver slippers, dragged the heavy dress over her head, rubbed at her cheeks with a towel. Water — lots of it. Soap. Clean — clean. That’s better. A comb through the brittle blonde curls. Henry would say: “Well, now you’ve done it, let ’em grow again. I like you best with it long. Lillian Russell — that’s your style.”

Henry! Henry! Where are you?

The maid had turned back the corners of the bedclothes and had placed with dramatic effect the crêpe de chine nightgown, that fragile, extravagant bit of fluff, hemstitched, pin tucked, girdled with knotted strands of baby-blue ribbon. Beneath it, pigeon-toed, a pair of blue satin mules. On the pillow, a cap of crocheted silk to put over her hair.

Bessie gathered these things up and threw them on the sofa. She went to the bureau and found, neatly folded, slightly yellowed and crumpled, a nainsook nightgown with sleeves. It was trimmed with Cluny lace. It was ample and soft and clean. She put it on.

There were slippers, too — comfies with silk pompons on the toes. Arrayed thus, with her hair slicked back and a soaped, shining countenance, she felt somehow protected. She pulled the blinds against the lighted city and knelt by the bed.

Illustrations by Harley Ennis Stivers

“The Old People” by Ida Alexis Ross Wylie

I.A.R. Wylie spent her childhood on long solo trips bicycling around the English countryside and cruising in Norwegian fjords. The “keen suffragist” published fiction furiously in England and the U.S., and many of her works, like Keeper of the Flame, were adapted into major films. Her 1926 story “The Old People,” set in 19th-century Bavaria, imparts the personal and political aspects of war, as an elderly couple who has lost everything struggles for a meager legacy against a brutal Italian officer.

Published on April 17, 1926

Trumpets. Even Andreas Hofner, who was very deaf, heard them. It was less a sound than a sudden burst of sunlight in the gray winter stillness. The trumpets were blown vigorously but rather unevenly, as though the trumpeters were running, and the faint unsteadiness gave the long blast a thrilling passionate quality, like the break in a human voice. Old Andreas heard it quite distinctly. He looked up from the wooden shield he was carving, absently dusting away some of the delicate shavings that had gathered under his hand, and took off his spectacles as though to listen better.

“Soldiers,” he said aloud.

He stood motionless. In the kitchen next his workshop, Maria, his wife, was clattering busily. He could not hear her, but he knew she was there and he knew that she would be clattering, because it was nearly time for the midday meal. And in the old days, when his hearing had been keen as a hunter’s, he had often smiled to himself, listening to her and thinking how she loved the crisp, clean clatter of her shining copper.

“Maria!” he called in his deep grumbling voice.

But she paid no attention, and he went slowly, with the heaviness of a great strength that has begun to fail, to the inner door. He opened it and the pleasant fragrance that greeted him was like a sound too. It made the fading blue eyes under the thick white brows twinkle. For a moment he forgot what he had wanted to say to her.

“Alterchen, there is something here that smells good.”

“You may well say so,” his wife shouted back cheerfully. “Leberwurst and Spezzel — that’s what it is.”

“Is it a feast day then?” Andreas asked doubtfully.

“Maybe it is. There are so many people on the streets you would think so. Look at them now.”

She pointed a twisted energetic old finger at the window under the smoke-blackened beams, and sure enough the townspeople were moving past in a slow stream. They did not look in as they usually did when they had time to spare. Their faces were grave and anxious, and when Maria Hofner tapped at the panes even Johann Kirsch, who was the Bürgermeister and Andreas’ oldest friend, only nodded hastily and hurried on.

“Perhaps someone has died,” Maria reflected. “But I don’t know who it could be. It is true that Gottfried Baum has had the fever for this last week

“If it had been Gottfried Baum,” Andreas interrupted severely, “I should have been the first to know. The relatives would have sent for me at once. Who else should make his coffin for him? Didn’t he always say, ‘There is no one who can handle wood like Andreas’?”

“It is true, of course,” Maria murmured soothingly. He could not hear her, but he had learned to read her lips.

“It was Gottfried who spoke up for me in the council. He said, ‘No one has a greater claim than Andreas. Andreas lost five sons. And he is the greatest craftsman in Windstättl. He will carve us the finest memorial in the whole of the empire.’”

“They say there isn’t an empire anymore,” Maria broke in. “I don’t understand what they mean, but they say there is no emperor.”

“People chatter a lot of nonsense,” Andreas retorted sternly. “What do the people here know about politics? They hear rumors and they make up fairy tales. If they worked harder they would have more sense.”

He stood watching her, his hand twisted in the short curly white beard that made him look like one of the shepherds that he had carved into the altarpiece for the parish church. These fits of dreaming had grown more frequent of late. While he worked at the memorial he had dreamed — so vividly that once or twice he had looked up and called a name; each time it had been Fritzchen because Fritzchen had been his favorite — and had waited with a thickly beating heart for a door to open. And it took time for him to remember that he was an old man and that Fritzchen and Albert and Kurt and Hans, and even baby Andreas, were all dead.

Maria bustled about. She was the very opposite of her husband. When she had been a girl she had been called the fairy of Windstättl because of her slender figure and tiny hands and feet, and at their marriage the town wits had made jokes about her and Andreas, who could have crushed her with one hand. As a matter of fact, he was very gentle and had never hurt anyone in his life. But all that had changed. The five sons had come and the war had taken them away, and pretty Maria Hofner had become an old misshapen woman, with a bent back and twisted feet that had lost their spring, and a shriveled, hard-bitten little face. But she had plenty of life left. All her movements were quick. She was like a little old sparrow hopping about the dim kitchen.

“Listen!” Andreas commanded.

Maria stopped with the lid of a saucepan in her hand. Yes, there it was again. She had heard it the first time — trumpets. Only this time they sounded nearer and had a harsh, exultant note that hurt the ears.

“Soldiers!”

“There are no soldiers,” Maria protested. “All the soldiers have gone away. Perhaps it is the Schültzenverein making an outing. What day of the year is it, Andreas?”

Andreas Hofner looked at the gaudy calendar that hung by the door. He tore off the forgotten leaves with his thick, strong fingers.

“Saint Hubert’s Day,” he told her.

Maria clucked her satisfaction.

“There then! Of course it’s the Schültzenverein. He’s their patron saint. But why they should make such a noise about it or why anybody should bother about them, goodness knows.”

Andreas went back to his work. Very soon the winter’s light would begin to fail and there was still the lettering to be finished. He had three days left, but his hand had lost something of its steadiness and he had to go slowly. One slip and the work of months might he spoiled. Andreas took the edges of the shield in his hands and bent over it, brooding on each strong, delicate line that for him represented a thought. He had never been outside Windstättl, but he knew in his heart that this was a noble thing that he had made — finer than the altarpiece, finer even than the Christ that from the top of the pass watched over the little town. In a small space Andreas had carved the majesty of the mountains, and at their feet slept a dead Austrian soldier. His face was lifted to the sun that rose just behind the topmost peak of the Königsberg, and even in miniature the peace of its expression was a thing for wonder and pity. Anyone who had known Fritz Hofner would have recognized him.

Fritz and Albert and Kurt and Hans and baby Andreas lay in the crowded military cemetery under the shadow of Königsberg, on whose bitter heights they had fought and died. The place was forlorn and neglected, because the people were too poor even to bring wreaths; and it was Andreas who had cut the simple white crosses and carved in the names and the regimental numbers of the dead heroes. But this was to be their true memorial. On Sunday he would nail it with his own hands to the Rathaus amidst the solemn prayers of the people. So long as the Rathaus stood, Fritz and Albert and Kurt and Hans and baby Andreas would never be forgotten.

Maria came in and stood beside him. A quietness settled about them both, so that they no longer heard the trumpets or the rush of feet. They were alone together. Maria pointed her stiff old finger.

“Für’s Vaterland,” she read aloud. “Ei, that’s got a grand sound to it, Alterchen, and only one more letter left to do.”

He nodded gravely. “It will be finished. I have worked night and day that it should be finished.”

“Ei, but everyone will be pleased when they see it. There isn’t another town in Austria that’ll have such a memorial. It’ll put heart into everyone. When they go past it people will lift their heads again.”

“No one has lost so much,” Andreas said. He said it proudly. Pride had been the only thing that had upheld him. When Fritzchen went — he was the last, swept away with a hundred comrades in an avalanche — the emperor himself had telegraphed. Everyone in Windstättl had seen the telegram. Such a thing had never before happened, and from then onward Andreas and Maria, with their five dead sons, had been set apart.

“There is to be a band,” Maria went on, “and the fire brigade from Eulensee is sending a deputation in uniform, and the bishop is to give the benediction from the Rathaus window. Oh, if they could only see it — the five Buberle — they would be proud too!”

Someone was rattling desperately at the door. Whoever it was was so frightened that they didn’t realize the door wasn’t locked. Maria opened it impatiently. A storm of noise seemed to rush past. There was Elsa, Kurt’s young wife, leaning against the jamb, wide-eyed and panting, her shawl clutched about her and her face grown old.

“Elsa, in Gottes namen what has happened?”

“Haven’t you heard, Mutterle? It’s the Italians — the Italian soldiers. They’ve come over the pass — they’re coming now — hundreds of them!”

She almost screamed, so that her voice sounded like one of the trumpets. The room was full of tumult. It was as though a tidal wave had burst in through the open door and was swirling against the walls, destroying, devastating.

But Andreas held himself steady. He made a proud sweeping gesture with his great arm.

“It’s not true,” he said. “You’re crazy, Elsa, my girl. The war is over. The Italians never came over the Königsberg. We saw to that. Our five sons — ”

Even as he spoke, the Bersaglieri swept past the window. They came at their historic trot, their plumed hats, at a gallant angle, flowing in the gray winter’s wind, their dark intent faces alight, their trumpets shouting.

Andreas strode to the door. “I tell you the war is over,” he said sternly. “It is a mistake. They’ve no right — ”

He was thrust back. The trumpets caught his protest on their hard, shining points of sound and tossed it aside. And Elsa, Kurt’s wife, who was with child, broke into bitter, terrified weeping.

II

The General Beppo Volpi rode with his aide-de-camp down the mountain pass and talked comfortably of old times. The winter’s sun had gone down behind the mountains, and the winding road, still torn by the passage of heavy military traffic, was steeped in cold gray shadow. But the peaks of the Königsberg blazed. The general, wrapped in his wide cloak, pointed at them. Though he was an old man, he had good eyesight; and besides, he knew what he could not see.

“That was my dugout,” he said; “there, on the left where the peak is forked. Twice we lost it and twice we won it back. The last time it came to a hand-to-hand struggle and the place was like a charnel house, so full of dead you could hardly move. And the cold — I shall never forget the cold — never, never. Sometimes I felt like a dead man myself; my limbs wouldn’t move. These mountains, which look so beautiful to you, my dear Strazzi, and over which the tourists will soon be swarming, picking up souvenirs, became to us demons semi-human, monstrous torturers. We cursed them, for every foothold cost us blood and agony. But we held on. If it hadn’t been for the peace we’d have taken this damned little rats’ nest at the point of the bayonet.”

“Doubtless,” the aide murmured politely. “The peace came too soon. We could have taught them a lesson.”

“We shall teach it them yet,” the general said, smiling under his gray mustache.

The two men fell silent. The aide was thinking of Rome, whence he came and which would be enjoying its first festivities since the war. It was hard luck. The prospect of spending the next months in this miserable village made him feel more than ever cold and discouraged. But the general was remembering his youth.

“You Romans don’t understand,” he said presently, as though he had guessed his companion’s thoughts. “I was born in Sedena — Kleinstadt they called it — in Italia Irredenta. We were Italians, every man of us, and we dared not even speak our own tongue. They had their heels on our necks and there was nothing for it but to set our teeth and wait. No, you couldn’t possibly understand what it means to me.”

He was a very handsome old man, very upright, with the fine, aquiline features of his race. But the aide, glancing shyly at him, thought involuntarily of the peaks that were now cold and gray as corpses. There was something deathlike in the implacable figure riding beside him. All very well to play avenger and conqueror, but as for the young aide, he would rather have danced at the Quirinal. He glanced up, however, courteously following his superior’s eyes. Though he had been in the war himself, it was hard to believe that men had actually lived and fought on these sinister and threatening heights.

In the shadow of the mountains, but far back from the road, they passed a walled-in space. In the center was a huge, roughly built cross, and at its feet, nestling like sheep at the feet of a shepherd, were hundreds of little crosses. Very ghostlike they looked in the shrouding twilight. The big cross had not been planted strongly enough to withstand the winter’s storms, and was bowed to one side in an attitude of sorrowful and protecting tenderness.

“Yes,” the general murmured, “we made them pay all right. There were more than that, though. Once a whole company was swept away by an avalanche and were never found. It was like an act of God.”

A chill wind, pregnant with snow, blew down the pass, and the general’s cloak spread out about him like black wings. His companion shivered. It looked very lonely up there in the neglected cemetery lonely and bitterly cold. He could not help imagining the place at night with the snow heaped high over the dead. He had to remind himself that, anyhow, the dead are alone and cold.

Lanterns glimmered ahead of them. They moved hither and thither as though they were afraid and were trying to gain courage from one another. As the two men rode up one of the lanterns advanced alone. It was lifted, showing a man’s stern anxious face. He stood at the general’s knee and tried to speak firmly and with dignity. But his lips quivered.

“Eure Excellenz, I am the Bürgermeister of Windstättl, and in the name of the citizens I protest — ”

The general touched his horse with his spurs so that the startled animal bounded to one side and, the man with the lantern had to scramble into safety. The general spoke loudly so that everyone could hear. His voice was so hard and metallic that it seemed to rise to the very tops of the black and silently witnessing mountains.

“The name of this town is Falzaro. You are Italian citizens.” He bent down from his saddle. “And you, sir, are no longer Bürgermeister.”

He rode on. He carried himself magnificently, as though behind him watched a regiment of his dead comrades. But on the lighted outskirts of the town he looked back.

“They shot my father,” he remarked casually. “You understand — he would not speak their language.” And then he laughed — the aide would have supposed at some light, perhaps rather improper story, had he not seen the old man’s face.

III

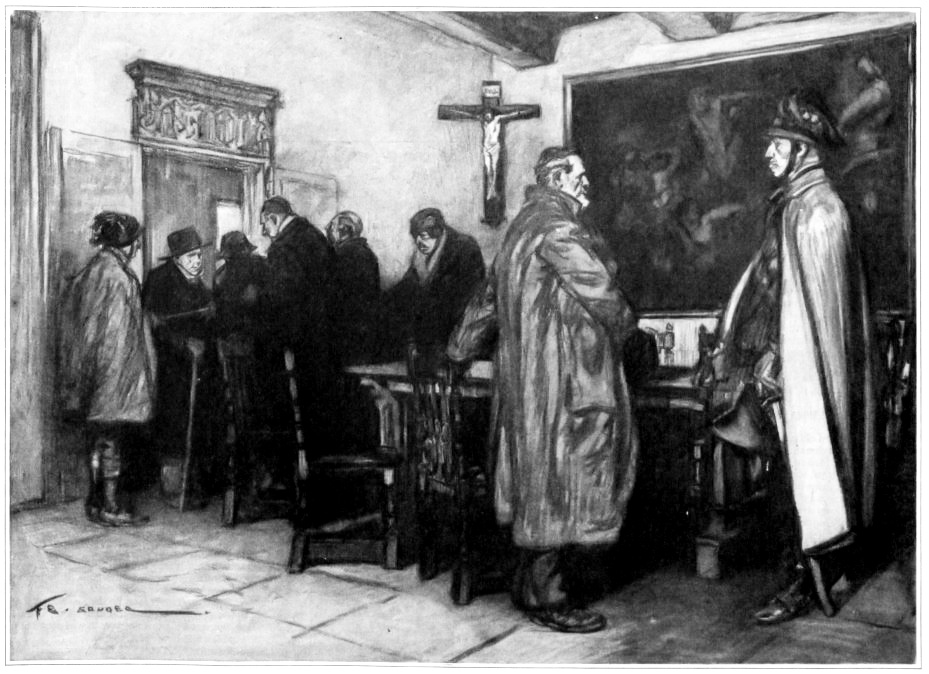

They sat together at the long oak table, and though the sentry at the door seemed to take no notice of them, they spoke in undertones. There was the ex-Bürgermeister Johann Kirsch, his brother Georg, the Herr Doktor Menzel, who was very old and kept forgetting what they had come about, and five of the chief tradesmen in Windstättl. Once upon a time they had been prosperous men and had carried their heads high and spoken their minds with robust voices. Now they whispered and kept their eyes down, as though they were afraid of what they might see, or as though they were secretly, tragically ashamed.

The Council Room of the old Rathaus was as familiar to them as their own homes. On winter evenings they had sat under the noble age-blackened beams, shrouding themselves in thick tobacco smoke and arguing comfortably about the town’s affairs, whilst the medieval paintings of saints and horribly tortured martyrs looked down on them with a complacent serenity.

But the room had grown cold. It had a dank, melancholy atmosphere, as though someone had died and lay in invisible state. It smelled of death. The sentry, silent and immobile, might have been on guard at the door of a mortuary. From time to time the eight men glanced at him wonderingly. It was like a dream. Even the noises below in the street had a nightmarish, unfamiliar quality. At any moment they might wake up, blink their eyes and clap the embossed lids of their beer mugs with a great sigh of relief.

“I must have dozed off. I had a devilish queer dream too. I’ll tell you what it was — aber zuerst, nosh eins, meine Herren!”

And they would fill up and lift their mugs with a jovial “Prosit, Alterchen!” whilst the smoke would sink in a kindly veil about them, blotting out that sinister, incredible figure.

Gottfried Keller, the baker, sat back, throwing out his chest and speaking in a loud uncertain voice.

“Na, he certainly doesn’t mind keeping us waiting. But Italians are like that — unpunctual, no system. I remember one time — ”

“Take care!” his neighbor whispered. “Take care, can’t you?”

The sentry glanced around. “Speak Italian,” he ordered curtly, “or hold your tongues!”

They held their tongues for a while, making odd self-conscious grimaces like scolded children. Then they began to whisper again, watching the door out of the corners of their eyes.

“Of course, it can’t be true,” the old Bürgermeister muttered. “What right have they? Even savages commemorate their dead. Still, one doesn’t want to make trouble — ”

The door opened. The sentry saluted smartly. The deputation lumbered to their feet. General Beppo Volpi glanced from one to the other of them with a cold military keenness that was without feeling or human curiosity. Compared to their peasant bluntness, he was like a fine rapier. As he came up to the table he tossed his cloak back, showing the array of ribbons on his breast.

“Well?” he queried. “Well, gentlemen?”

They stammered. Each one of them made a little deprecatory sound, so that it was like a subdued hum. The ex-Bürgermeister began in German and then broke off and started again in rough Italian.

“If you please, it is like this: On Sunday we are to put up a memorial to our dead heroes. It had been arranged before you — ” he made a vague gesture like someone who has been mortally wounded and does not yet know what has happened to him “ — before Your Excellency — in fact before we knew of these changes — of what they had done to us up there. It was to have been a great celebration — a religious celebration, you understand. Our master craftsman has carved a shield which is to hang outside the Rathaus — ”

“The Palazzo Municipale,” General Volpi corrected, throwing down his thick military gloves.

“Ah, yes, of course.” The Bürgermeister ducked his head in docile acknowledgment. “A deputation is being sent from all the surrounding villages and the bishop is to pronounce his blessing from the Rathaus — from the Palazzo window.”

“I have already notified the bishop that the ceremony will not take place.”

They looked at one another. Then it was true. The Bürgermeister began again. He was trying to speak firmly yet quietly, as he had done two nights before on the road. But the military figure, standing at the head of the table, locked in an attitude of static impatience, made him tremble.

“Excellenz, that is what we have heard. But we could not believe it. I would not have taken any notice, but I was afraid — I did not want any misunderstanding. After all, authority is authority. I, as Bürgermeister, understand that — ”

The soldier glanced at him — one sharp, ironical glance, and the speaker faltered. “I mean — I understand — my time of office — I did not want any conflict. I wished to work with you to keep the peace. Since nothing can help us, we wish to do our best. That is why we have come so that the matter should be clear.”

“It is clear.”

The Bürgermeister’s mouth opened. It stayed open and began to tremble oddly, like that of a child on the verge of tears. But the Herr Doktor Menzel nodded and rubbed his hands as though he were congratulating everybody on a satisfactory case. He was very old and hadn’t heard clearly.

“You see,” he chirped — “you see, I told you so. What an unnecessary fuss! In these days we are all civilized, decent people. I told you it would be all right.”

They tried to silence him, tugging him by the sleeve and whispering in his ear. They knew they ought not to have brought him, but he had been on the council for years and had done no harm. Therefore it had seemed cruel to leave him out. Besides, he was a gentleman, a university man, not a rough peasant like themselves, and the general would surely be impressed. But the general measured him with a restrained contempt.

“Perhaps it is time you people understood your position once and for all. By the treaty you have become subject to the Italian Government. Your suggestion that you should celebrate your resistance to our arms is therefore a piece of insolence that you would be wise not to repeat.”

“Excellenza — ”

The soldier brought his fist crashing on the table. “My father was shot by your people for less,” he said. “Now you can go.”

They shuffled their feet. They wanted to go. They were terrified — they hardly knew at what. Something about this iron old man broke them, so that if he had lifted his fist, resting clenched and hard as a block of stone on the table, they would have winced. But the Bürgermeister held his ground desperately.

“Excellenza, it is our dead we honor.”

“Ah, yes, the men who killed our men — my men up there on the Königsberg — my son, for that matter. Excellent! Evidently you have a sense of humor. . . . Now get out of here. You have had my answer. I am in full authority for the time being and you are under martial law. You know, I suppose, what that means.”

“Si, si, Excellenza.”

They ducked obsequiously. But the Bürgermeister had grown suddenly quite calm. It was as though he had come out of terrifying doubt and darkness into some place where he was not afraid because he knew that nothing mattered anymore.

“Forgive me, Excellenza, I don’t think you understand. Our sons died for the fatherland as yours did. It seems they were beaten, but they did their best. They gave all they had. There are no young men left in Windstättl, Excellenza — only us old people. I do not speak of my own sons — I will not speak of myself at all. I think perhaps it is of no great consequence what you and I decide or what happens to us two. In a very few years the dust will be over everything. But there are those in this town who will feel your order, Excellenza, as though it slew their children a second time. I am thinking of old Andreas Hofner and his wife. Excellenza, all their boys went — five in one year. We thought at first they would lose their minds. If they had not felt that their boys had died gloriously, their hearts would surely have broken. Even now they don’t understand and we dare not tell them. For a whole year Andreas has worked at his shield. It is a fine thing, Excellenza — even you would say so — a thing to touch the heart. He is a great craftsman, our Andreas. He carved the crucifix that stands at the head of the pass. Your Excellency must have seen it.”

The general motioned to the sentry. “Get these men out.”

“Excellenza, they are very old, sad people. I dare not tell them. Think — five sons in one year — even the emperor telegraphed. It is only a little thing to allow them — a wooden shield.”

The sentry came with his rifle crossed and began to push them along, hustling them with an emotionless insistence. They went like frightened sheep scrambling for the exit to their pen. But the Bürgermeister stood quietly at his place, his head bent meditatively, and when the sentry touched him he made a stern gesture so that the man involuntarily fell back from him. At the door he turned and bowed to the general, and the General Beppo Volpi, yielding to an instinct stronger than his purpose, touched his cap.

Outside, the deputation huddled together. It was very cold. An icy wind raced down the medieval little street. But it was not the wind that made their teeth chatter. They were unmanned and ashamed. They did not dare speak or look at one another.

It was market day. The street was full of peasants interlaced with carabinieri parading two and two like solemn twin dolls, and smart Italian officers with their caps at a rakish, victorious angle. Amidst so much movement and color, the deputation had a forlorn gray look like a group of prisoners who have been thrust out into the world and no longer know where to turn.

It was Gottfried Keller who said at last, “We must tell them. You will have to tell them, Herr Bürgermeister.”

“I am not Bürgermeister any more, Herr Keller, and I will not tell them.”

“Who will then?”

“God knows, I cannot.” He clenched his hands. “Let them find out for themselves what men are made of,” he added bitterly.

The Herr Doktor Menzel plucked at his sleeve. “Gentlemen, I will tell them. Who has more right to such a task? Didn’t I bring their five sons into the world?”

“Yes, that is true. Let the Herr Doktor tell them.”

They sighed their relief. No doubt it was true that he was a little mad, the Herr Doktor, but he was kind and had skillful hands. He would break Andreas Hofner’s heart and the heart of Maria his wife very, very gently.

IV

He had forgotten. He knew that he had forgotten. For two whole days he had known, and now he stood at the door of Andreas Hofner’s house, plucking his lips with trembling fingers and making little moaning sounds under his breath like someone in torment. It was terrible. He remembered how eager he had been. He had pushed himself forward, determined to show them all that he still counted for something; and they had trusted him, and for an hour or so he had gone about with his head up, feeling resolute and confident again. Then a kind of drowsy mist had settled on his brain and he had forgotten.

Of course he should have gone frankly to Johann Kirsch and told the truth. But he was too ashamed. Once upon a time he had been the cleverest man in Windstättl and people had looked up to him and asked his advice. Now they shook their heads and said, “He forgets, poor old fellow — he forgets everything.” And he could not bear it. He would rather have died than to have gone to them and said, “I have forgotten.”

Everything seemed to combine together to trouble him. The Sunday morning was so still — so very strangely still. It was as though everyone had deserted him. Except for the inevitable carabinieri, who paraded slowly backward and forward, looking about them with puzzled, doubtful eyes, the streets were empty. The windows of the houses had kept their shutters closed. Even the church bells were silent. There was an air of desolate mourning as though the little town covered its face with its hands and wept.

The Herr Doktor did not understand. Perhaps it was the threat of a storm that kept the people hidden. Certainly there was a queer gray light over the Königsberg, whose final peak stood up like a finger against the livid sky. Yes, there was snow coming. But the people of Windstättl were not afraid of snow. He shook his head and rapped timidly. Perhaps when he saw the Hofners everything would come back.

Maria Hofner opened the door to him. At first he was so astonished that he couldn’t speak. Why, she had been married in that dress! Queer that he should remember so vividly something that belonged to forty years back and couldn’t remember what people had said to him only two days ago. But there it was; he remembered every detail. The light embroidered bodice and full flowered skirt, the close-fitting beaded headdress, such as the Windstättl women had worn in the Herr Doktor’s youth, were more familiar to him than his own shrunken hands. But they made her unfamiliarly gnarled and small and twisted. The dress was so new, as though it had been laid out on the bride’s bed only yesterday, and she was so old. For one grisly moment the Herr Doktor thought that the whole of his life had been a dream and that at the touch of some evil magic Andreas Hofner’s pretty wife had withered in her bridal clothes.

He became more confused. He could see that her bright, birdlike eyes were peeping Past him anxiously, right down the street, seeking for someone.

“Na, na, Herr Doktor, it wasn’t you we expected. But nevermind. Come inside, and the others will be along presently.”

“Presently — presently,” the Herr Doktor murmured.

He followed her into the living room. There, too, something had happened — something solemn and touching. The room had been cluttered with life, with a turmoil and struggle of hard-won existence — the birth of children, their tears, their laughter, farewells, unspoken anxiety, crushing grief and stoic silences. Sometimes it had seemed to the old doktor that he could see the ghosts of all the room had witnessed — that the very walls had been impregnated with voices and unheard sighing.

But now the place was empty, swept and garnished as for the coming of some great event. The copper pots and pans gleamed on the walls. The oak table, drawn up in the corner under the crucifix, gleamed like a dark, empty mirror. The clock ticked solemnly. Life had been put away. It was like a church, austere and hushed. And set against the wall, facing the door, as if in welcome, was the carved shield of the Windstättl memorial.

Ah, yes, the memorial. The Herr Doktor remembered now — dimly. Of course. They were to hang the shield today on the wall of the Rathaus. They had been on a deputation to the Italian general about it and the Italian general had said — what had he said? The Herr Doktor groaned secretly. It was as though a gust of wind had blown to the door of his mind, and though he might fling himself against it pitifully, it would not yield. He had to stand outside, shivering and helpless.

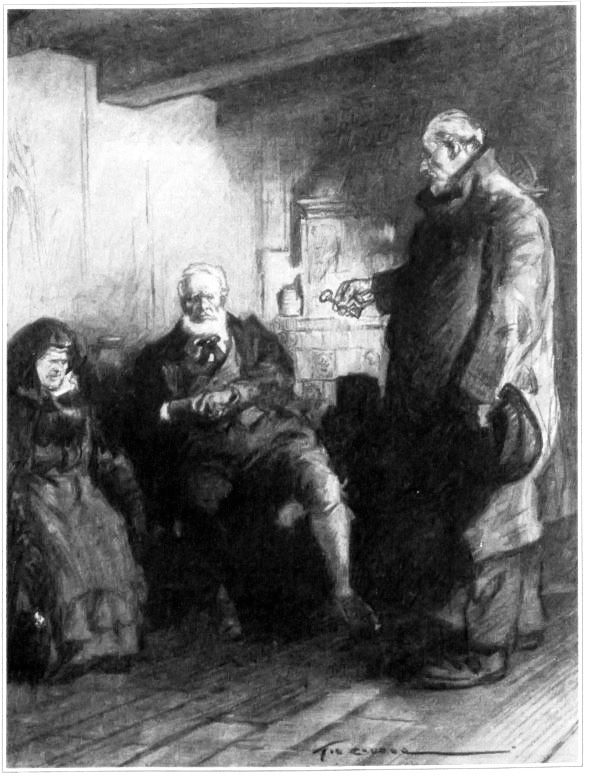

But it couldn’t go on. He had to say something. He could see how puzzled they were. The old woman was watching him with her head a little on one side, and he imagined that there was a look on her wizened face as though she knew the thing he couldn’t remember and was afraid. And Andreas himself was watching — waiting for the solemn, tremendous thing to happen.

The Herr Doktor remembered him as a slim handsome young man, but he had grown stout and heavy, and the Tyrolean wedding dress didn’t fit him anymore. He might have been comic — an old man masquerading — but there was an earnest, touching dignity about him. The Herr Doktor had to turn away. He felt dazed and sick with his uncomprehending pity.

“Well, well, that’s fine — that’s fine,” he stammered. “A grand piece of work. Yes, indeed. You must be very proud, Andreas.”

“Are they coming — the others?” Andreas asked. “They were to have been here by now. I was getting anxious. I thought, ‘Suppose there should have been some mistake. Suppose those Italian scoundrels — ’ Why — why do you look like that, Herr Doktor?”

“It is nothing — nothing at all,” the Herr Doktor declared cheerfully. Somebody behind the closed door had whispered to him, but so faintly he couldn’t hear. He went across to the carved shield and ran his shaking hand over its polished surface. “Yes, most beautiful, most touching, as the Herr Bürgermeister said; a thing to move the hardest heart.”

“Did he say that?”

“Indeed he did. . . . Perhaps — perhaps in a moment I shall remember something more.”

“Ei, Kirsch is a good fellow,” Andreas Hofner murmured. He stood in an attitude of perplexity, his hand clenched in his thick, gray hair. “But why does he keep us waiting? The bishop is to give the blessing in half an hour. They are cutting it pretty fine, those fellows. And how quiet everything is. No one in the streets. I thought — ” He glanced about him confusedly, as though for a moment he doubted the reality even of his own surroundings. “I had thought somehow — ”

His wife shuffled over to him. She slipped her withered arm through his and fixed the Herr Doktor with her strange penetrating look that seemed to say, “Take care — take great care what you do to him.”

“Perhaps they sent the Herr Doktor with a message,” she suggested. “Perhaps all the people are waiting outside the Rathaus. Is that what you were to tell us, Herr Doktor?”

He nodded eagerly. He felt grateful to her. She couldn’t open the door, but she could make him see what was perhaps beyond it. And somehow old Andreas frightened him. He had the tense, strained look of someone balanced on the edge of a precipice who daren’t look down for fear of what he shall see.

“That’s it — that’s it exactly. The streets are so crowded — to tell you the truth I was all confused — I am not so young anymore — I had to fight my way through — ”

“And the band — is there a band playing?”

“All the time, all the time — the band from Eulensee. Fine fellows they are, playing for all they’re worth.”

“Do you hear them, Maria?”

“Yes, yes; now I can just hear them.”

She and the old doctor listened to the silence. Andreas Hofner sighed. His glance wandered to the clock, ticking solemnly among the shadows.

“We should be going,” he said restlessly. “I don’t understand. They were to have come for me. Four men from the Schutzverein were to have carried the shield.”

“Perhaps if the Herr Doktor could remember his message — ” she insisted. “ Perhaps he was sent to fetch us.” She said distinctly, under her breath, “Tell me! What is it? What is the matter? Why don’t they come?” But he could only stare back helplessly. How could he say to her, “I have forgotten”? And perhaps it was true. Perhaps he had come to fetch them. If only it had not been for that rising, breathless pity in him as though someone behind the closed door of his mind knew and wept.

“Yes, that’s just it. I was to fetch you. At the last moment things had to be changed. It was the Italian general. He said — things had to be changed. I can’t explain now. But we ought to go.” He drew out his watch. For two days, in his misery, he had forgotten to wind it, and he stared at its dead face with unseeing eyes. “Yes, yes, Andreas, we ought to go.”

The old man sighed again. “I had thought it would be different,” he said wistfully. He picked up the shield and set it heavily, sadly on his shoulders. “Open the door, Maria.”

The Herr Doktor went out behind them. The street was full of a gray, penetrating cold. Yes, snow was coming. He felt his knees giving way under him. Something was going to happen — something quite terrible. These two old people were walking straight to meet it and he ought to stop them. But if he said “Don’t go,” he would have to explain that he was a poor old man who had lost his wits, and he couldn’t bear it. The tears came into his eyes and he rubbed them back with his knuckles. It was pitiable to be so old.

“The windows are all closed,” Andreas Hofner said. “And there are no flags. Why are there no flags, Herr Doktor?” But he was so accustomed to not hearing he did not notice that they did not answer. Presently he asked again, “Can you hear the bands now, Maria?”

“Yes — yes, indeed. They are growing louder, Andreas.” But she fell back, plucking at the doktor’s sleeve. “What has happened? In the name of God, what is happening?”

He had to reassure her. “Nothing — nothing — I give you my word.” But it was of no good. He felt how his face lost its composure and broke up like the face of an unhappy child. He turned away from her. “I don’t know — I tell you I don’t know.”

Andreas Hofner’s house lay on the outskirts of the town, and they made their way through narrow twisting alleys toward the Kaiserstrasse, which was now the Corso Emmanuel. A wind was rising and came down from the mountains in short, cruel gusts that nearly carried them off their feet.

“Winter and death,” the Herr Doktor thought. “Winter and death.” He couldn’t think of anything else. Everything was old and dying — old Andreas there, bowed under his shield, and his little wife trotting at his heels — like a pathetic procession of things past and half forgotten. Even the two carabinieri stopped to look after them as though they, too, saw how queer and tragic they were — these three old people blown along by the wind.

But the street was empty.

A group of soldiers loitered in the archway of the Rathaus. They had been chattering with one another, but as they saw Andreas Hofner and his escort they fell silent and watched curiously. And as Andreas saw them he stopped short and set down his shield, and looked about him. He saw the emptiness and the silence and his face, flushed with exertion, went ashen.