The Five Closest U.S. Presidential Elections

In racing, whether horse or auto or foot, they call it a photo finish. That’s a result that’s so close that it’s almost impossible to discern with the naked eye, necessitating careful examination of a still picture to determine the winner. While you can’t resolve an election with a simple photo, history is loaded with contests that have been, at many points, too close to call. Though the rule of law and an orderly transition have been the norms in the United States since its inception, that’s not to say that arriving at a winner hasn’t on occasion been a rocky or contentious ordeal. With that in mind, here are the five closest presidential elections in the history of the United States.

Before digging in, one acknowledgement that you have to make is that the election is decided by the quirk of all quirks, the electoral college. The electoral college’s votes decide the outcome of the election, regardless of the outcome of the popular votes; though most presidential elections have “matched up” in terms of who won both the popular and electoral majorities, there have been five separate occasions when the “winner” lost the popular vote but was nevertheless conferred the presidency by the electoral college. Since the college is the final arbiter of victory, this list will be concerned with the closet elections in terms of the college; if you’re curious about the five closest in terms of the popular vote, those were: Kennedy over Nixon, 1960 (popular margin of 500,000 votes); Garfield over Hancock, 1880 (7,368 votes); Gore over Bush, 2000 (Gore had 500,000 more votes, but lost via the electoral college); Tilden over Hayes, 1876 (if you’re saying you don’t remember a President Tilden, you’re right; Tilden’s 250,000 more popular votes couldn’t tip Hayes’s electoral victory); and John Quincy Adams over Andrew Jackson (just wait).

So then, here are the closest presidential elections in terms of the electoral college.

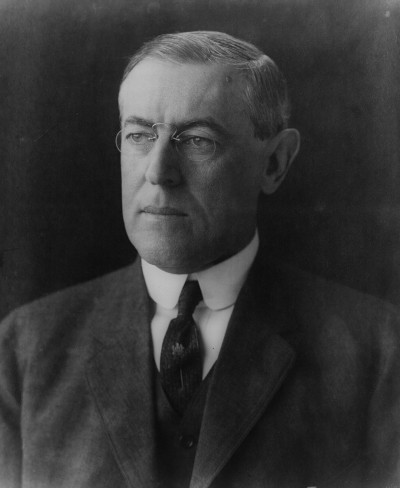

5. Woodrow Wilson vs. Charles Evans Hughes (1916)

Hughes was the former Republican governor of New York and a Supreme Court justice, and Wilson was the incumbent president. Wilson campaigned heavily on the fact that he had thus far kept the U.S. out of World War I. Ultimately, the desire to keep America out of the war proved to be too strong a force for Hughes to overcome. Wilson received 277 electoral votes to Hughes’s 254. In a historic bit of irony, the U.S. was fully immersed in World War I by April of the following year.

4. John Adams vs. Thomas Jefferson (1796)

Adams and Jefferson had a complicated, sometimes fiery, relationship. They were friends in the Continental Congress, served under first president George Washington together (with Adams as vice president and Jefferson as secretary of state), and later became bitter political rivals. Though they eventually mended fences and had years of correspondence with one another before dying on the same day (July 4, 1826), the 1796 election was one of their first heated moments of competition. Washington had the opportunity to run for another (third) term, but opted out. Adams and Jefferson both ran with running mates, but by a quirk of the rules that would later be altered in 1804 by the 12th Amendment, electors of the electoral college could vote for each person separately regardless of running mate, giving Adams 71 votes and Jefferson 68. By the rules as they stood, Adams became president, and his opponent became his vice president.

Honorable Mention: Thomas Jefferson vs. John Adams (1800)

This doesn’t quite count because of its overall strangeness, and it’s a situation that wouldn’t happen again today due to rules updates and the 12th Amendment. In a rematch of 1796, Jefferson and Adams ran against one another. However, this time there were formalized tickets, and Jefferson ran with Aaron Burr, while Adams had Charles Pinckney as his running mate. The rules being what they were, electors could cast votes for the individuals, rather than the ticket, so it ended up that Jefferson and Burr were tied with 73 electoral votes. That led to the election being decided in the House of Representatives, with Alexander Hamilton famously influencing the vote for Jefferson (the events of the election were described, albeit in a somewhat fictionalized manner, in “The Election of 1800” in Hamilton: An American Musical).

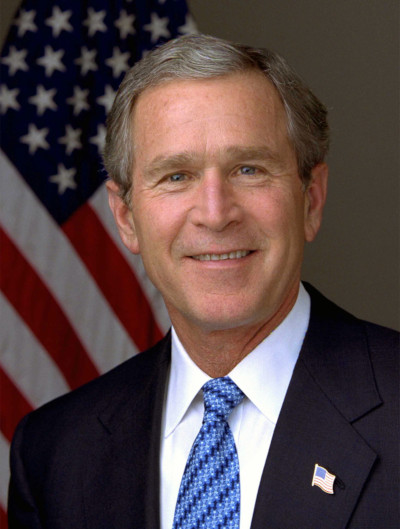

3. George W. Bush vs. Al Gore (2000)

We’ve already established that Gore won the overall popular vote. Of course, it all comes down to the electoral side. At issue was the fate of Florida’s 25 electoral votes, which would be the tipping point for either candidate. Things were so close that Gore called Bush to concede, and then took his concession back. Florida went into a statewide machine recount, as the popular vote would determine the disposition of the electoral vote; Gore also asked for a manual recount in four crucial counties. The Bush campaign sued to stop the recount, which triggered a run of decisions and appeals that went up to the Supreme Court. The Supreme Court ordered the recount stopped by December 12; at the stoppage, Bush was ahead by 537 votes. Florida’s electoral votes went to Bush, and he became president by a margin of 271 to 266.

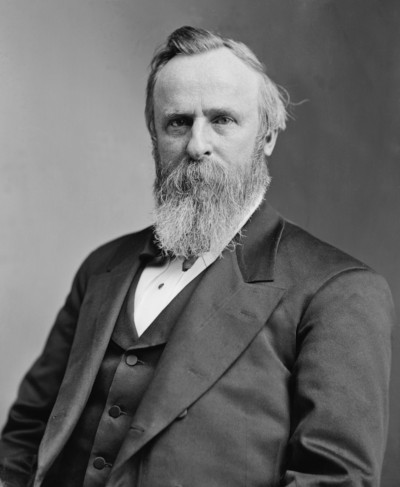

2. Rutherford B. Hayes vs. Samuel Tilden (1876)

This would be the closest election (in fact, the Post once called it the “worst election”) if it weren’t for the unprecedented action that followed in the Number One slot. The initial electoral count showed Tilden ahead of Hayes by a margin of 184 to 165. The 20 votes of Oregon, Florida, South Carolina, and Louisiana remained in dispute, with both sides declaring victory. Wheeling and dealing led to an agreement that’s called the Compromise of 1877; the states offered their electoral votes to Hayes if he would essentially end Reconstruction and withdraw remaining Union troops from the South. The deal was struck, and Hayes defeated Tilden by a single electoral vote, 185 to 184.

1. 1824: John Quincy Adams vs. Andrew Jackson

Going into 1824, there were four proper candidates: Secretary of State (and son of John Adams) John Quincy Adams, Tennessee Senator Andrew Jackson, Secretary of the Treasury William Crawford, and House Speaker from Kentucky, Henry Clay. Vice presidential candidates were voted on separately; in fact, Clay and Jackson would both receive votes in the category. The field of four candidates split the electoral vote; while Jackson initially had the most, he did not have enough for the electoral threshold. The breakdown was Jackson with 99, Adams with 84, Crawford with 41, and Clay with 37. With no majority winner, the decision then went to the House of Representatives, where each state would get one vote agreed upon by their reps. The 12th Amendment limited the field to three, so Clay was out. However, Clay, who hated Jackson, actively worked to get representatives from areas where he earned votes to support Adams. Adams won 13 states, and the presidency; Jackson finished with 7, and Crawford, 4. Jackson was enraged, as he had won the popular vote and the most electoral votes, but still lost. Making matters worse, Adams appointed Clay to secretary of state. Jackson would allege corruption, making it a centerpiece of his campaign; it helped him ride to victory in his rematch with Adams in 1828.

Featured image: andriano.cz / Shutterstock

Obama Wins Nobel for Peace

For the third time in its history, the Norwegian Nobel Committee awarded its Peace Prize to an American president in office.

The committee chose President Obama from 205 candidates (172 individuals, 33 organizations) whose names had been submitted as part of the committee’s annual process.

The choice of Obama surprised most Americans, as well as the international reporters in Oslo, Norway, where the announcement was made.

Obama took office in January, only two weeks before the deadline for submitting nominees. In the short time that followed, it appears, the Nobel committee was impressed with his efforts to improve diplomacy and eliminate nuclear arsenals. They must have considered his efforts to build understanding between America and the Muslim world in a Cairo speech, and his United Nations speech urging greater global unity. They also would have known that this peace candidate was waging war in both Iraq and Afghanistan.

The committee did not have to name a winner. Between 1901 and the present, the committee has refused the prize in 19 years.

President Theodore Roosevelt won the Peace Prize in 1906 for brokering a peace between Russia and Japan, which was threatening to destabilize Asia and possibly the Russian government.

Woodrow Wilson won the prize in 1919 for his efforts to end World War I and build a global League of Nations, which he believed would prohibit future wars.

In 2002 the committee gave its award to ex-president Jimmy Carter for his efforts, both in and out of office, to support peace and help struggling nations. And in 2007, former vice president Al Gore was the recipient for his international efforts on behalf of the environment.

The list of past winners is long and includes many now-obscure names. Many, though, should be familiar to us: Albert Schweitzer, George C. Marshall, Dag Hammarskjöld, Linus Pauling, Martin Luther King Jr., the International Red Cross, Anwar Al-Sadat, Mother Teresa, the Dalai Lama, Mikhail Gorbachev, and Nelson Mandela.

But the Peace Prize doesn’t always come with a supply of peace. The choices in the past have been controversial. Many were angered when the committee gave the award to Henry Kissinger in 1973, and even more were disappointed that it was never given to Mahatma Gandhi.