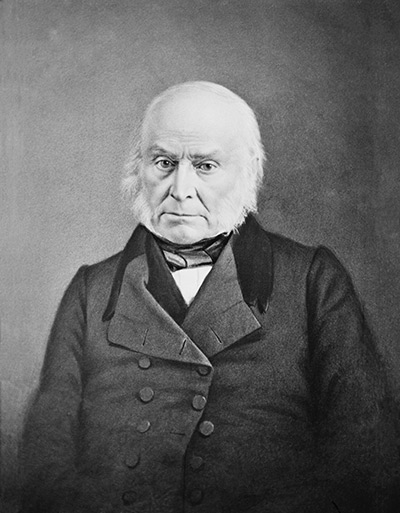

For decades, the conventional wisdom has been that former presidents return to private life after leaving office. Granted, they’ll take on speaking engagements, write books, paint, produce shows for Netflix, and endorse other candidates, but they don’t generally run for office again. That may be how it is now, but that’s not how John Quincy Adams did things. The first son of a president to become president himself, Adams was only the sixth person to hold the office. But that was far from the only office that he would occupy in an extremely long run at many levels of public service.

John Quincy Adams was born in 1767, the oldest of John and Abigail. When the elder Adams went to Europe on diplomatic missions during the American Revolution, the 12-year-old John Quincy accompanied him. He studied multiple languages and even worked in Russia for American statesman Francis Dana for two years. After more time spent in the Netherlands and Great Britain, Adams and his father returned to the U.S. in 1785. He attended Harvard, then law school, and saw his father become the first vice-president of the United States in 1789. Though he engaged in political writing while practicing law, he wouldn’t officially enter politics until 1794 at age 27.

1794-1796 – Ambassador to the Netherlands: Adams was an easy choice for president George Washington. He was a known quantity in the country, and his father had negotiated for Dutch assistance during the Revolution. During this period, Adams met Louisa Johnson, his future wife.

1796-1801 – Ambassador to Portugal, then Prussia: Washington switched Adams’s mission to Portugal in 1796; after the elder Adams was elected president later in the year, he appointed his son as ambassador to Prussia (the Imperial predecessor of modern Germany). When President Adams lost the next election to Thomas Jefferson, John Quincy stepped down from his post.

1802-1803 – State Senator in Massachusetts: That didn’t last long, because . . .

1803-1808 – U.S. Senator from Massachusetts: The state legislature of Massachusetts appointed Adams to the U.S. Senate. Though a Federalist when he joined the Senate, Adams began a long career of being a voice of challenge; Adams supported the Louisiana Purchase and general expansion. He quarreled with his own party after various issues involving Britain, notably impressment (that is, forcing people into service); the party rift grew such that the legislature selected his successor before his term was out, and he left the Senate entirely as its conclusion.

1809-1812 – United States Minister to Russia: After spending time teaching at Brown and Harvard and arguing a case in front of the U.S. Supreme Court (Fletcher v. Peck), Adams returned to the diplomatic life when president James Madison appointed him the first Minister to Russia. In 1811, Madison wanted to make Adams a Supreme Court Justice, but he declined, as his heart was in diplomatic work.

1812-1817 – British Delegation/Ambassador to Britain: While Adams was still in Russia, the War of 1812 broke out between the U.S. and Great Britain. Madison made Adams part of a delegation to try to end the war. A bid by Tsar Alexander to mediate between the two powers failed, so Adams left Russia by 1814. The American and British delegations met that year in Belgium to try to end the war; they delivered a treaty by Christmas Eve, 1814. The following May, Madison made Adams the official Ambassador to Britain. When James Monroe was elected president, he recalled Adams to the United States for a new job.

1817-1825 – Secretary of State: The new president had been the Secretary prior to his election, and he selected Adams to succeed him. Adams had few peers with his depth of experience and pre-existing relationships in Europe. During his tenure, Adams would help the U.S. acquire Florida from Spain, set wheels in motion that would cement Oregon’s place in the country, and helped draw down military presence for both the U.S. and Britain around the Great Lakes area. Adams and Monroe were also concerned with building relationships in Latin America and South America. As various countries emerged from European control, they set policies to limit Europe’s influence in their former colonies. That became the Monroe Doctrine, the notion that America would not interfere in inter-European affairs if Europe left the Americas alone.

1825-1829 – President of the United States: The Election of 1824 turned out to be both extremely complicated and historic. Five candidates vied for the office, including Adams’s old diplomatic (and sparring) partner Henry Clay, John C. Calhoun, William Crawford, and General Andrew Jackson. No candidate received the required majority of electoral votes, which led to the contingent election codified in the Twelfth Amendment. Adams won the day, and the presidency. He also made two lasting cosmetic changes to the office; Adams dispensed with the powdered wig to show his own short hair and got rid of knee breeches in favor of trousers. Yes, John Quincy Adams brought pants to the presidency.

Adams turned out to be a one-term president, losing the election of 1828 to Jackson. The former president almost retired entirely from public life, and the heaviness on his heart only increased when his son, George Washington Adams, committed suicide the following year. However, general boredom and a growing disdain for Jackson lit a fire under Adams to do something that very few former presidents have ever done: run for office again.

Sir Anthony Hopkins played John Quincy Adams in Steven Spielbeg’s Amistad. (Uploaded to YouTube by Movieclips)

1831-1848 – Representative from the State of Massachusetts: Adams ran for Congress in 1830 and won. He was 64 years old when he began his term 189 years ago this week. Adams would go on to win a remarkable nine times, serving all the way up until his death in 1848 at age 80. From his place in Congress, Adams was in the office against the backdrop of five different presidents (Jackson, Martin Van Buren, one month of William Henry Harrison, John Tyler, and James K. Polk). He worked hard in support of the sciences and was the driving force of what became the Smithsonian Institute. Adams opposed the Mexican-American War and turned out to be the most prominent American voice arguing for the abolition of slavery. He returned to argue in front of the Supreme Court in the case of United States v. Amistad, speaking for four hours on behalf of slaves who revolted and seized the Spanish vessel; Adams won the case, which ended with Supreme Court granting the slaves freedom and returning them home.

While casting a vote in Congress on February 21, 1848, Adams suffered a cerebral hemorrhage on the floor of the House. He died two days later in the Speaker’s Room of the Capitol Building with Louisa, his wife of more than 51 years, at his side. It’s no small irony, and perhaps entirely appropriate, that he literally took his last breaths inside one of the institutions to which he’d devoted his life. His last recorded words were, “This is the last of earth. I am content.”

Today, Adams is largely remembered in a general sense for simply being the first president that was the son of a president. That does a critical disservice to his instrumental role in any number of historic endeavors. Widely considered one of the more intelligent presidents and certainly an admirable diplomat, it was Adams’s broad range of skill and ability that helped him continually resurface in public life. Maybe it’s up to modern America to take the time to give Adams a new kind of return, one to more public awareness of his crucial role in our common history.

Featured image: John Quincy Adams’s tomb in Quincy, MA.(Joseph Sohm / Shutterstock)

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

Thank you for pointing that out. We must have missed that when the article was published early last year. Thanks again!

I’m really surprised that The Saturday Evening Post misspelled Mathew Brady’s name.