Despite the great technological advances since the introduction of the bicycle in the early 1800s, its liberating image has remained almost unchanged; it has always provided a healthy, inexpensive, and environmentally friendly means of transportation. But even more so, the bicycle opened doors for women, inextricably linking function, fashion, and freedom.

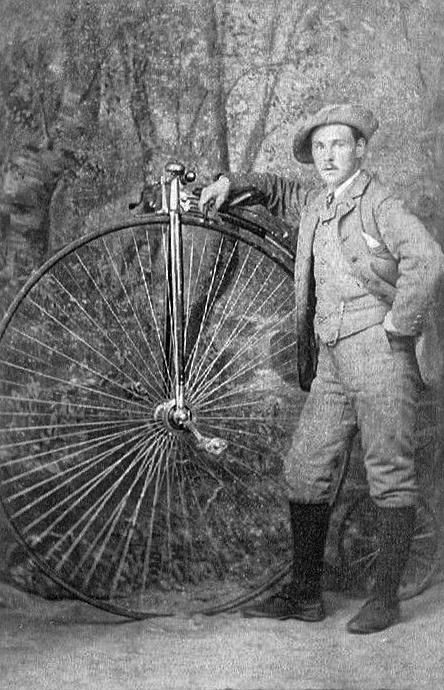

The history of the bicycle is connected to the social developments that characterized American society in the late 19th century such as urbanization and the rise of leisure culture Earlier models, which were difficult to mount and hard to balance, limited the bicycle to an “extreme sport.” But by 1885, the introduction of the safety bicycle — which included two equally sized wheels with air-filled rubber tires — made the bicycle lighter and easier to operate, turning it into the “people’s carriage.”

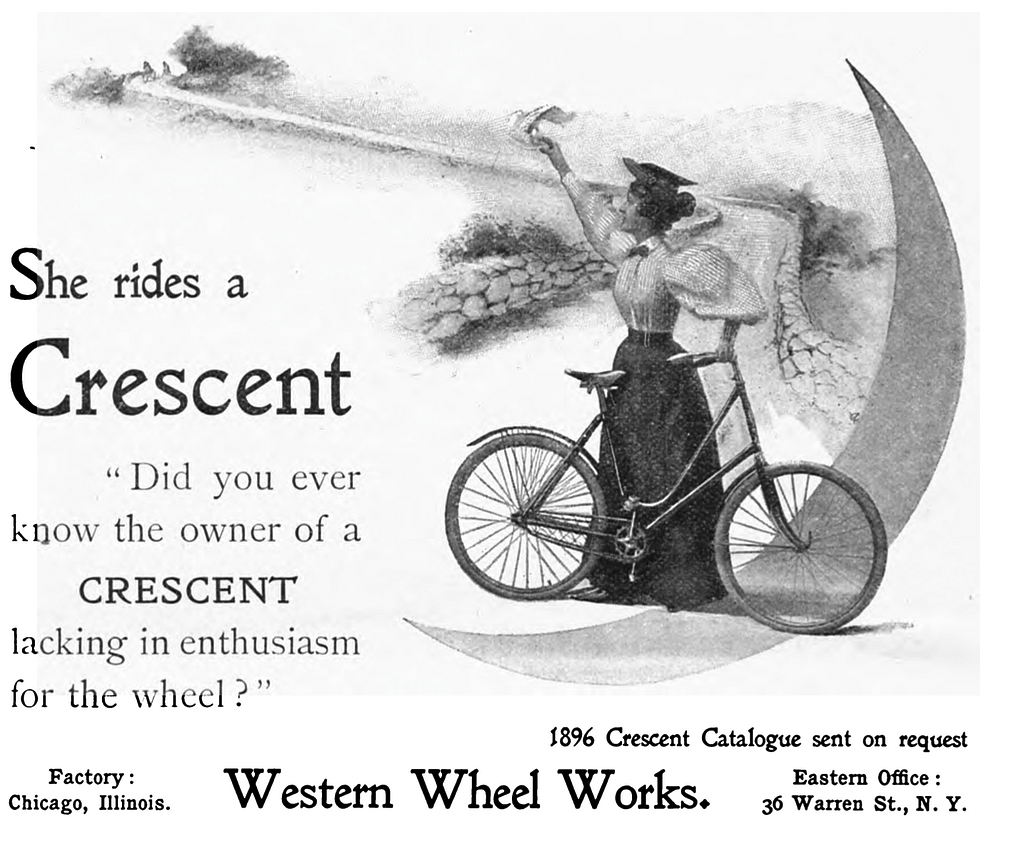

Perhaps more importantly, the safety bicycle also included a dropped-frame design that accommodated women’s skirts while riding. Indeed, while both sexes rode bicycles, they appealed mostly to women who made it a national craze by the 1890s; it became a socially appropriate leisure activity, especially for the middle classes. Unlike other sports with long-standing traditions or gender affiliations (such as horseback riding), cycling was a new activity that allowed women to adopt it more easily and to claim dominance in it.

Marking a new public presence and new possibilities of mobility, contemporaries were quick to point to the liberating potential of the bicycle, especially to women. In 1896, woman’s rights advocate Susan B. Anthony claimed that the bicycle has “done more to emancipate women than anything else in the world.” According to her, it was a “picture of free, untrammeled womanhood.”

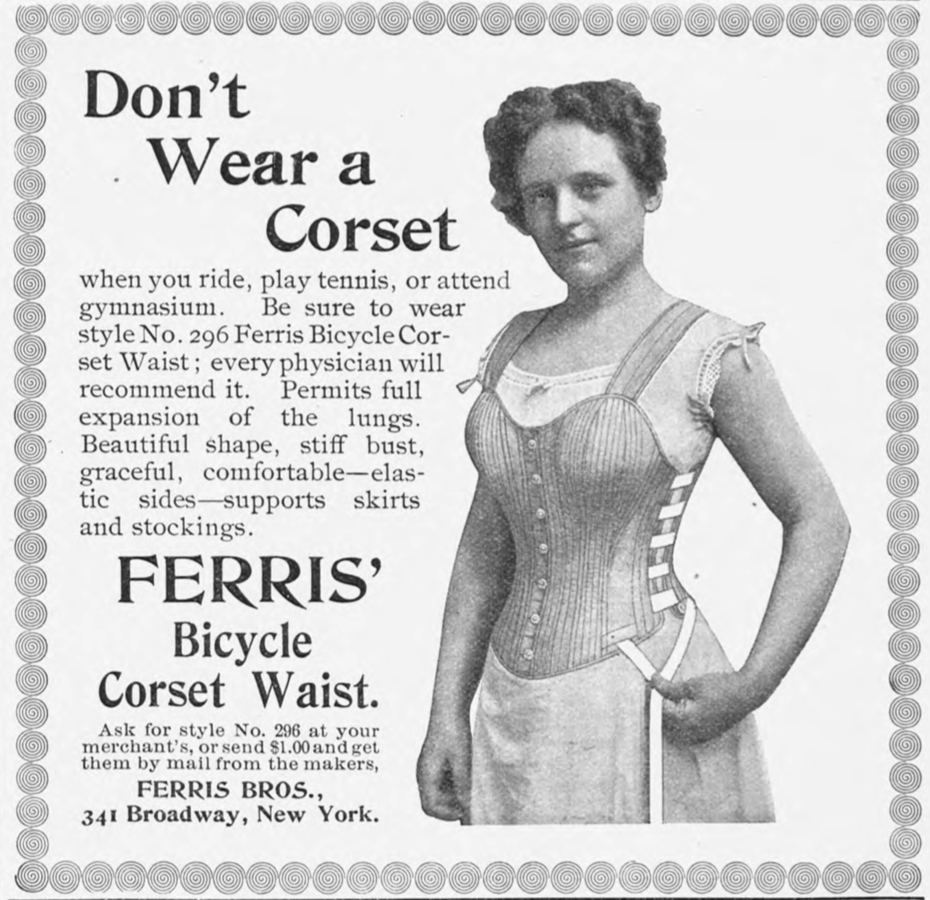

Yet, it was not cycling alone that became the symbol of emancipated femininity. More than anything, the changes in fashion that cycling popularized provided women with a true sense of freedom. The bicycle contributed to the loosening of corsets and to the revival of bloomers —the infamous dress reform initiative of the 1850s that featured a short dress layered over trousers and was associated with the agitation for women’s rights. Suffragist Elizabeth Cady Stanton welcomed that development, arguing sarcastically that finally, the world would recognize that women too have two functional legs and are willing to use them.

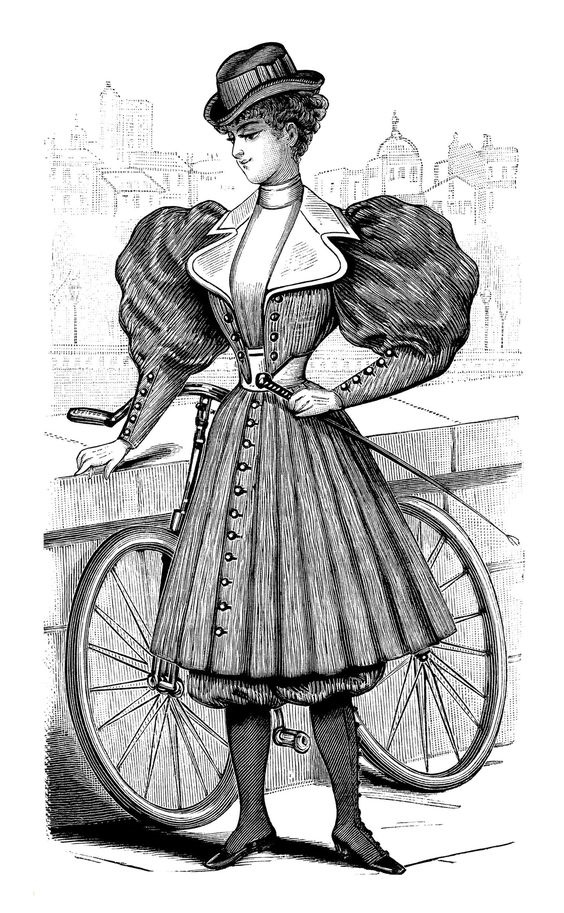

However, the bicycle did not popularize pants for women. Since cycling was an outdoor public activity, often done in a mixed-sex setting, it was also a courting activity, and as such, women were more reluctant to challenge gender norms through their attire. While more daring women, who saw cycling as a political activity, adopted bloomers, most women preferred to stick to clothes that enhanced their femininity rather than challenged it.

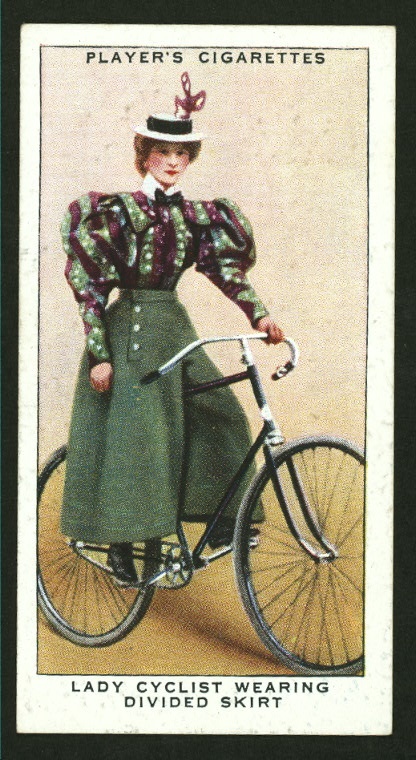

For those who didn’t want to wear bloomers, the fashion industry offered a few attractive alternatives. One was the divided skirt: a standard gored skirt with a split pleat in the back, which enabled the wearer to straddle the rear wheel. This option was a reasonable compromise for women who wanted to maintain the appearance of the skirt without relinquishing the convenience of bloomers. However, the more popular solution was the “short” skirt, with a length that varied from knee to calf, according to the preference of each rider and the message she wanted to convey while cycling.

The popularity of the short skirt reached beyond bicycle riding. As women increasingly began to venture into public spaces, the workplace, and higher education, they sought to adjust their clothes to the new reality of movement and service. They took advantage of the fact that people became more accustomed to the presence of cycling women in public and adopted the short skirt in other contexts. Especially women who needed to walk and get around in city streets viewed the short bicycle skirt as a potential solution to the problem of the ills of trailing skirts.

In 1896, some New York society and professional career women founded the Rainy Day Club to advocate for the use of the short skirt not only for cycling but also for everyday use, especially on bad weather days. Members included doctors, novelists, reporters, and other businesswomen, who saw themselves as modern career women in search of appropriate and comfortable outfits to wear in the streets, offices, and meetings. These women formed a connection between fashion, beauty, and comfort, translating their ideas regarding women’s freedom into sartorial reality.

From its beginning, the club drew a lot of media attention. Dubbed “Rainy Daisies” by the press, a nickname the club later embraced, the group used this publicity as a vehicle to promote their cause. Club members sought to induce women to abandon their trailing skirts in favor of comfortable outfits, regardless of weather. Taking their inspiration from cycling attire, they constructed their own “rainy-day costume” that included a short skirt, jacket, and a high boot.

The utilitarian benefits of the outfit — ease of movement and better health because the shorter length kept skirts off of the wet and dirty streets — could not be contested according to club members. Yet the greatest joy that members had in wearing the rainy-day outfit was in the sense of dignity and confidence that wearing such an outfit gave them. Arguing that the rainy-day costume provided both beautiful and functional solution to their needs, club members constructed a positive link between beauty and utility.

Club members took pride that they designed their own rainy-day dresses, yet the pattern and ready-made industries also offered rainy-day skirts to the middle-class woman who did not want to make them herself. Despite their relative popularity and availability, rainy-day outfits — like the bicycle — remained mainly a middle-class fad.

While the vision of Rainy Daisies storming the streets never fully materialized, the club did have some influence in turning the “short” skirt into an acceptable mainstream fashion. As the 20th century progressed, the club’s approach towards simplicity of lines and the emphasis that form should follow function, gained popularity through the styles of the liberated flapper.

Seeking mobility and comfort both on and off the wheel, women used the popularity of the bicycle to carve themselves an evolving presence in the public sphere, creating a new image of femininity. Combining ideas of comfort and mobility with style and beauty, the bicycle and its fashions helped to advance women’s freedom at the turn of the 20th century.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

Thank you bob! I’m glad you enjoyed reading.

Another terrific feature, Einav! I did not know that much about this topic previously, but that’s changed now thanks to you. Love the historical research you put into it here with some unique photos, ads and artwork accompanying the role the bicycle played in the late 1800’s for women in getting around on their own.

As far as fashion goes, it certainly helps (at least in part) to explain how and why the styles for women became much more liberated in the relatively short time between the 1900’s and the ’20s. The Rainy Day Club here is pretty interesting. What you write of here was only to the good for women, just to throw in my opinion.

The very talented 19th century writer and feminist Fanny Fern (great 2018 Post feature) would have embraced the bicycle too, had it not been something after her time. This same feature includes ‘Rainy Days’. written as only she could. In closing, there’s one vintage image of a woman on her bicycle that’s perhaps the ultimate: Miss Gultch riding hers very fast, before briefly and shockingly morphing into her infamous alter ego!