Making the Case for AA

AA had its beginnings in 1935 when a doctor and a layman, both alcoholics, helped each other recover and then developed, with a third recovering alcoholic, the organization’s guiding principles. By 1941, the group had demonstrated greater success in helping alcoholics than any previous methods and had grown to about 2,000 members. But for most of North America, AA was still unknown. Following the March 1, 1941, publication of an article written by Jack Alexander in The Saturday Evening Post (see “Alcoholics Anonymous,” below) describing AA’s extraordinary success, inquiries began to flood in, leaving the small staff of what was then a makeshift headquarters overwhelmed. Alcoholics Anonymous tripled in size in the next year and continued to grow exponentially. Today, 75 years later, AA claims 2 million members worldwide, 1.2 million of them in the U.S. Following are links to the original Post article that many credit for AA’s success and two of Jack Alexander’s follow-up articles.

Read Jack Alexander’s articles on Alcoholics Anonymous:

“Alcoholics Anonymous”

by Jack Alexander

“A Skeptical Journalist”

by Jack Alexander

“The Drunkard’s Best Friend”

by Jack Alexander

A Skeptical Journalist

Editor’s note: Four years after his groundbreaking article on AA was published, writer Jack Alexander recalled his initial doubts about the group in an AA publication.

It began when the Post asked me to look into AA as a possible article subject. All I knew of alcoholism at the time was that, like most other non-alcoholics, I had had my hand bitten (and my nose punched) on numerous occasions by alcoholic pals to whom I had extended a hand — unwisely, it always seemed afterward. Anyway, I had an understandable skepticism about the whole business.

My first contact with actual AAs came when a group of four of them called at my apartment one afternoon. This session was pleasant, but it didn’t help my skepticism any. Each one introduced himself as an alcoholic who had gone “dry,” as the official expression has it. They were good-looking and well-dressed, and as we sat around drinking Coca-Cola (which was all they would take), they spun yarns about their horrendous drinking misadventures. The stories sounded spurious, and after the visitors had left, I had a strong suspicion that my leg was being pulled. They had behaved like a bunch of actors sent out by some Broadway casting agency.

Excerpt from “Jack Alexander of SatEvePost Fame Thought AAs Were Pulling His Leg,” AA Grapevine, May 1945

Read Jack Alexander’s articles on Alcoholics Anonymous from the Post archive:

“Alcoholics Anonymous”

by Jack Alexander

“The Drunkard’s Best Friend”

by Jack Alexander

The Drunkard’s Best Friend

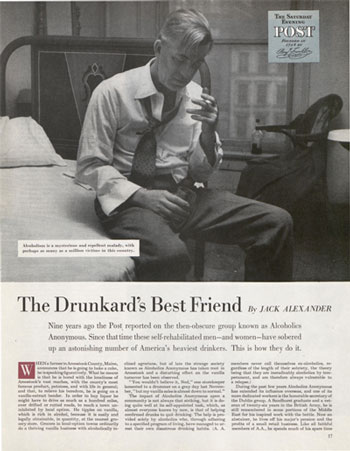

Editor’s note: In 1941 the Post reported on the then-obscure group known as Alcoholics Anonymous. Since that time these self-rehabilitated men — and women — have sobered up an astonishing number of America’s heaviest drinkers. This is how they do it.

When a farmer in Aroostook County, Maine, announces that he is going to bake a cake, he is speaking figuratively. What he means is that he is bored with the loneliness of Aroostook’s vast reaches, with the county’s most famous product, potatoes, and with life in general; and that, to relieve his boredom, he is going on a vanilla-extract bender. In order to buy liquor he might have to drive as much as a hundred miles, over drifted or rutted roads, to reach a town uninhibited by local option. He tipples on vanilla, which is rich in alcohol, because it is easily and legally obtainable, in quantity, at the nearest grocery store. Grocers in local-option towns ordinarily do a thriving vanilla business with alcoholically inclined agrarians, but of late the strange society known as Alcoholics Anonymous has taken root in Aroostook and a disturbing effect on the vanilla turnover has been observed.

“You wouldn’t believe it, Ned,” one storekeeper lamented to a drummer on a gray day last November, “but my vanilla sales is almost down to normal.”

The impact of Alcoholics Anonymous upon a community is not always that striking, but it is doing quite well at its self-appointed task, which, as almost everyone knows by now, is that of helping confirmed drunks to quit drinking. The help is provided solely by alcoholics who, through adhering to a specified program of living, have managed to arrest their own disastrous drinking habits. (AA members never call themselves ex-alcoholics, regardless of the length of their sobriety, the theory being that they are ineradicably alcoholics by temperament, and are therefore always vulnerable to a relapse.)

During the past few years Alcoholics Anonymous has extended its influence overseas, and one of its more dedicated workers is the honorable secretary of the Dublin group. A Sandhurst graduate and a veteran of twenty-six years in the British Army, he is still remembered in some portions of the Middle East for his inspired work with the bottle. Now an abstainer, he lives off his major’s pension and the profits of a small retail business. Like all faithful members of AA, he spends much of his spare time in shepherding other lushes toward total abstinence, lest he revert to the pot himself.

The honorable secretary is a man of few spoken words, but he carries on a large correspondence within the fraternity. His letters, which are notable for their eloquent understatement, are prized by fellow AAs in this country and are passed around at meetings. One of his more fascinating communiqués, received here in October, described a missionary trip to Cork, in company with another AA gentleman. The purpose of the trip was to bring the glad tidings of freedom to any Corkonians who might happen to be besotted and unshriven, and to stimulate the local group, which was showing small promise. This was the honorable secretary’s chronological report:

- 8 p.m. The chairman and myself sat alone.

- 8:05 One lady arrived, a nonalcoholic

- 8:15 One man arrived

- 8:20 A County Cork member arrived to say he couldn’t stay, as his children had just developed measles.

- 8:25 The lone lady departed.

- 8:30 Two more men arrived.

- 8:40 One more man arrived, and I decided to make a start.

- 8:45 The first man arrival stated that he had to go out and have a drink.

- 8:50 He came back.

- 8:55 Three more arrived.

- 9:10 Another lady, propped up by a companion, arrived, gazed glassily around, collected some literature and departed unsteadily.

- 9:30 The chairman and I had finished speaking.

- 9:45 We reluctantly said good night to the new members, who seemed very interested.

In summing up, the secretary said: “A night of horror at first, developing quite well. I think they have good prospects, once the thing is launched.”

To a skeptic, the honorable secretary’s happy prognosis in the face of initial discouragement may sound foolishly hopeful. To those already within the fraternity and familiar with the sluggardly and chaotic character of AA local-group growth in its early stages, he was merely voicing justifiable optimism. For some years after its inception, in 1935, the Alcoholics Anonymous movement itself made slow progress. As the work of salvaging other drunks is essential to maintaining the sobriety of the already-salvaged brethren, the earnest handful of early salvagees spent some worrisome months. Hundreds of thousands of topers were prowling about in full alcoholic cry, but few would pause long enough to listen.

Six years after it all began, when this magazine first examined the small but encouraging phenomenon (Post, March 1, 1941), the band could count 2000 members, by scraping hard, and some of these were still giving off residual fumes. In the nine years which have intervened since that report, the small phenomenon has become a relatively large one. Today its listed membership exceeds 90,000. Just how many of these have substantial sobriety records is a matter of conjecture, as the movement, which has no control at the top and is constantly ridden by maverick tendencies, operates in a four-alarm-fire atmosphere, and no one has the time to check up. A reasonable guess would be that about two thirds have been sober for anywhere from six months to fifteen years, and that the rest have stretched out their periods of sobriety between twisters to the point where they are at least able to keep their jobs.

The intake of shaky-fingered newcomers, now at its highest in AA history, is running at the rate of around 20,000 a year. The number that will stick is, again, a matter of conjecture. If experience repeats, according to AA old-timers, about one half will stay sober from the start, and one fourth will achieve sobriety after a few skids; the other one fourth will remain problem drinkers. A problem drinker, by definition, is one who takes a drink for some compulsive reason he cannot identify and, having taken it, is unable to stop until he is drunk and acting like a lunatic.

How Many of the Four Million Will Join?

It is tempting to become over sanguine about the success of Alcoholics Anonymous to date. Ninety thousand persons, roaring drunk or roaring sober,

are but a drop in the human puddle, and they represent only a generous dip out of the human alcoholic puddle. According to varying estimates, between 750,000 and 1,000,000 problem drinkers are still on the loose in the United States alone. Their numbers will inevitably be swelled in future years by recruits from the ranks of between 3,000,000 and 4,000,000 Americans who, by medical standards, drink too much for their own good. Some of these millions will taper off or quit when they reach the age at which the miseries of a hangover seem too great a price to pay for an evening of artificially induced elation; but some will slosh over into the compulsive-drinker class.

The origins of alcoholism, which is now being widely treated as a major public-health problem, are as mysterious as those of cancer. They are perhaps even harder to pin down, because they involve psychic as well as physical elements. Currently, the physical aspect is being investigated by universities and hospitals, and by publicly and privately financed foundations. Some large business and industrial firms, concerned about reduced productivity and absenteeism, are providing medical and psychiatric aid to alcoholic employees. The firms’ physicians are also digging into the alcoholic puzzle. The most plausible tentative explanation that any of these investigative efforts has come up with is that alcoholism is a sickness resembling that caused by various allergies.

Psychiatry has its own approach to the problem; it is successful in only a small percentage of cases. Clergymen, using a spiritual appeal, and the beset relatives of alcoholics, using everything from moral suasion to a simple bat in the jaw, manage to persuade a few chronics to become unchronic. So does one school of institutional treatment, which insists that alcoholism is solely the result of “twisted thinking” and aims at unraveling the mental quirks.

But the Alcoholics Anonymous approach — which leans on medicine, uses a few elementary principles of psychiatry and employs a strong spiritual weapon —is the only one which has done anything resembling a mop-up job. Whatever one’s attitude toward AA may be, and a lot of people are annoyed by its sometimes ludicrous strivings and its deadpan thumping of the sobriety tub, one can scarcely ignore its palpable results. To anyone who has ever been a drunk or who has had to endure the alcoholic cruelties of a drunk—and that would embrace a large portion of the human family — 90,000 alcoholics reconverted into working citizens represent a massive dose of pure gain. In human terms, the achievements of Alcoholics Anonymous stand out as one of the few encouraging developments of a rather grim and destructive half-century.

Drunks are prolific of excuses for their excessive drinking, and the most frequent alibi is that no one really understands what a struggle they have. With more than 3,000 AA groups at work in the United States, and every member a veteran of the struggle, this excuse is beginning to lose its validity, if it ever had any validity. In most cities of any size the fraternity has a telephone listed in its own name. A nickel call will bring a volunteer worker who won’t talk down to a drunk, as the average nonalcoholic has a way of doing, but will talk convincingly in the jargon of the drunk. The worker won’t do any urging; he will describe the Alcoholics Anonymous program in abbreviated form and depart. The drunk is invited to telephone again if he is serious about wanting to become sober. Or a drunk, on his own initiative or in tow of a relative, may drop in at the AA office, where he will receive the same non-evangelistic treatment. In the larger cities the offices do a rushing trade, especially after weekends or legal holidays. Many small-town and village groups maintain clubrooms over the bank or feed store; in one Canadian town the AAs share quarters with a handbook operator, using it by night after the bookie has gone home. Some of these groups carry a standing classified advertisement in the daily or weekly newspaper. If they don’t, a small amount of inquiry will disclose the meeting place of the nearest group; a local doctor, or clergyman, or policeman will know.

To some extent, the same easy availability obtains in the twenty-six foreign countries where AA has gained a foothold. This is especially true of the nations of the British Commonwealth, particularly Canada, Australia and New Zealand, which together list more AA members than the whole movement could boast nine years ago; and of the Scandinavian countries, where membership is fairly strong. At a recent AA banquet in Oslo, Norway, 400 members celebrated their deliverance, drinking nothing stronger than water. Throughout Scandinavia the members bolster the program by using Antibuse, the new European aversion drug. This practice is deplored by some AA members as showing a lack of faith in the standard AA program, but, of course, nothing is done, or can be done, about it, since the program is free to anyone who thinks he needs it and he may adapt it in any way that suits him.

More often than not, though, disregard of the standard admonitions backfires. A bibulous Scottish baronet found this out when, returning from London, where he caught the spark from a local group, he set out ambitiously to dry up Edinburgh, a hard-drinking town. But he tried it by remote control, so to speak, hiring a visiting American AA to do the heavy work. This violated the principle that the arrested drunk must do drunk-rescuing work himself in order to remain sober. Besides, the Scottish drunks wouldn’t listen to a hired foreign pleader. In no time at all, and without getting a convert, the baronet and his hireling were swacked to the eyeballs and crying on each other’s shoulders. After the American had gone home the baronet stiffened up, abandoned the traditions of his class and started all over again, cruising the gutters himself, visiting drunks in their homes and in hospitals and prisons. Edinburgh is now in the of win column, and there are also groups in Glasgow, Dundee, Perth and Campbeltown, all offshoots of Edinburgh.

Alcoholism on a large scale seems to be most common in highly complex civilizations. These tend to breed the neuroses of which uncontrolled drinking is just one outward expression. A man in a more primitive setting, bound closely to earthy tasks and the constant battle with Nature, is apt to again. It is treat his frustrations by ignoring them or by working them off.

Alcoholics Anonymous has nevertheless caught on in some out-of-the-way places. A liquor salesman for a British firm, who was seduced by his own merchandise, started a group in Cape Town, South Africa, which now has ninety members. There are also groups in Johannesburg, Pretoria, Bloemfontein, Durban and East London, and in Salisbury and Bulawayo, Southern Rhodesia. The group at Anchorage, Alaska, which started in a blizzard, has a dozen-members, including one slightly puzzled Eskimo, and there are small groups in Palmer and Ketchikan. There is a small group in his the leper colony at Molokai, nurtured by AAs from Honolulu, who fly there occasionally and conduct meetings.

The figures perhaps give too rosy a picture of the turbulent little world of Alcoholics Anonymous. Most of the a members of any standing seem to be exceptionally happy people, with more the serenity of manner than most non-alcoholics are able to muster these jittery days; it is difficult to believe that they ever lived in the drunk’s bewitched world. But some are still vaguely unhappy, though sober, and feel as if they were walking a tight wire. Treasurers occasionally disappear with funds and wind up, boiled, in another town. After this had happened a few times, groups were advised to keep the kitty low, and the practice now is to spend any appreciable surplus on a cake-and-coffee festival or picnic. This advice does not always work out; last year the members of a fresh and vigorous French-Canadian unit in Northern Maine, taking the advice to heart, debated so violently about how to spend their fifty-four dollars that all hands were drunk within 24 whole series of rebuffs. It is difficult at first for the recruit to achieve serenity.

As most groups are mixtures of men and women, a certain number of unconventional love affairs occur. More than one group has been thrown into a maelstrom of gossip and disorder by a determined lady whose alcoholism was complicated by an aggressive romantic instinct. Such complications are no more frequent than they are at the average country club; they merely stand out more baldly, and do more harm, in an emotionally explosive society. Special AA groups in 66 prisons around the nation are constantly trickling out graduates into the civilian groups. The ex-convicts are welcomed and are, for some reason, usually models of good behavior. A sanitarium or mental hospital background causes no more stir in an AA group than a string of college degrees would at the University Club; the majority of AAs are alumni of anywhere from one to fifty such institutions. Thus Alcoholics Anonymous is something of a Grand Hotel.

The ability of the arrested drunk to talk the active drunk’s language convincingly is the one revolutionary aspect of the AA technique, and it does much to explain why the approach so often succeeds after other have failed. The rest of the technique is a synthesis of already existing ideas, some of which hare centuries old. Once a community of language and experience has been established, it acts as a bridge over which the rest of the AA message van be conveyed, provided the subject is receptive.

Across the bridge and inside the active alcoholics’ mind lies an exquisitely tortured microcosm, and a steady member of Alcoholics Anonymous gets a shudder every time he looks into it again. It is a rat-cage world, kept hot by alcohol flame, and within it lives, or dances, a peculiarly touchy, defiant, and grandiose personality.

There is a sage saying in AA that “an alcoholic is just like a normal person, only more so.” He is egotistical, childish, resentful, and intolerant to an exaggerated degree. How he gets that way is endlessly debated, but a certain rough pattern is discernible in most cases. Many of those who ultimately become alcoholics start off as an only child, or as the youngest child in a family, or as a child with too solicitous a mother, or a father with an over-severe concept of discipline. When such a child begins getting his lumps from society, his ego begins to swell disproportionately – either from too easy triumphs or, as compensation, from being rebuffed in his attempts to win the approval of his contemporaries.

He develops an intense power drive, a feverish struggle to gain acceptance of himself at his own evaluation. A few of the power-drive boys meet with enough frustrations to send them into problem drinking while still in college or even while in high school. More often, on entering adult life, the prospective alcoholic is outwardly just about like anyone else his age, except that he is probably a little more cocky and aggressive, a little more hipped on the exhibitionistic charm routine, a little more plausible. He becomes a social drinker – that is, one who can stop after a few cocktails and enjoy the experience.

But at some place along the line his power drive meets up with an obstacle it cannot surmount – someone he loves refuses to love him, someone whose admiration he covets rejects him, some business or professional ambition is thwarted. Or he may encounter a whole series of rebuffs. The turning point may come quickly or it may be delayed for as long as 40 or 50 years. He begins to take his drinks in gulps, and before he realizes it he is off on a reeler. He loses jobs through drunkenness, embarrasses his family and alienates his friends. His world begins to shrink. He encounters the horrors of the “black-out,” the dawn experience of being unable to remember what he did the night before— how many checks he wrote and how large they were, whom he insulted, where he parked his car, whether or not he ran down someone on the way home. In the alcoholic world a nice distinction is made between the “black-out” and the simple “pass-out,” the latter being the relatively innocuous act of falling asleep from taking too much liquor. He jumps nervously whenever the doorbell or telephone rings, fearing that it may be a saloonkeeper with a rubber check, or a damage-suit lawyer, or the police.

He is frustrated and fearful, but is only vaguely conscious that his will, which is strong in most crises, fails him where liquor is concerned, although this is apparent to anyone who knows him. He nurses a vision of sobriety and tries all kind of self-rationing systems, none of which works for long. The great paradox of his personality is that in the midst of his troubles, his already oversize ego tends to expand; failure goes to his head. He continues, as the old saying has it, to rage through life calling for the headwaiter. In his dreams he is likely to see himself alone on a high mountain, masterfully surveying the world below. This dream, or some variant of it, will come to him whether he is sleeping in his own bed, or in a twenty-five-dollar-a-day hotel suite, or on a park bench, or in a psychopathic ward.

If he applies to Alcoholics Anonymous for help, he has taken an important step toward arresting his drink habit; he has at least admitted that alcohol has whipped him. This in itself is an act of humility, and his life thereafter must be a continuing effort to acquire more of this ancient virtue. Should he need hospitalization, his new friends will see that he gets it, if a local hospital will take him. Understandably, many hospitals are reluctant to accept alcoholic patients, because so many of them are disorderly. With this sad fact in mind, the society has persuaded several hospitals to set up separate alcoholic corridors and is helping to supervise the patients through supplying volunteer workers.

To the satisfaction of all concerned, including the hospital managements, which find the supervised corridors peaceful, more than 10,000 patients have gone through five-day rebuilding courses. The hospitals involved in this successful experiment are: St. Thomas’ (Catholic) in Akron, St. John’s (Episcopal) in Brooklyn and Knickerbocker (nonsectarian) in Manhattan. They have set a pattern which the society would like to see adopted by the numerous hospitals which now accept alcoholics on a more restricted basis.

Early in the game the newcomer is subjected to a merciful but thorough deflating of his ego. It is brought home to him forcefully that if he continues his uncontrolled drinking—the only kind he is capable of—he will die prematurely, or go insane from brain impairment, or both. He is encouraged to apologize to persons he has injured through his drunken behavior; this is a further step in the ego-deflation process and is often as painful to the recipient of the apology as it is to the neophyte AA He is further instructed that unless he will acknowledge the existence of a power greater than himself and continually ask this power for help, his campaign for sobriety will probably fail. This is the much-discussed spiritual element in Alcoholics Anonymous. Most members refer to this power as God; some agnostic members prefer to call it Nature, or the Cosmic Power, or by some other label. In any case, it is the key of the. AA program, and it must be taken not on a basis of mere acceptance or acknowledgment, but of complete surrender.

This surrender is described by a psychiatrist, Dr. Harry M. Tiebout, of

Greenwich, Connecticut, as a “conversion” experience, “a psychological event in which there is a major shift in personality manifestation.” He adds: “The changes which take place in the conversion process may be summed up by saying that the person who has achieved the positive frame of mind has lost his tense, aggressive, demanding, conscience-ridden self which feels isolated and at odds with the world, and has become, instead, a relaxed, natural, more realistic individual who can dwell in the world on a live-and-let- live basis.”

The personality change wrought by surrender is far from complete, at first. Elated by a few weeks of sobriety, the new member often enters what is known as the “Chautauqua phase” — he is always making speeches at business meetings on what is wrong with the society and how these defects can be remedied. Senior members let him talk himself out of this stage of behavior; if that doesn’t work, he may break away and form a group of his own. If he does this, he gradually becomes a quiet veteran himself and other Chautauqua-phase boys either oust him from leadership of his own group or break away themselves and form a new group. By this and other processes of fission the movement spreads. It can stand a lot of outstanding foolishness and still grow.

Drunks, as such, are too individualistic to be organized, and there is no top command in Alcoholics Anonymous to excommunicate, fine or otherwise penalize irrational behavior. However, services—such as publishing meeting bulletins, distributing literature, arranging for hospitalization, and so on – are organized in the larger centers. The local offices, which are operated and financed by the groups thereabouts, are autonomous. They are governed by representatives elected by the neighborhood groups to a rotating body called the Inter-group. There are no dues; all local expenses are met by a simple passing of the hat at group meetings.

A certain body of operational traditions has grown up over the years, and charged with maintaining them— by exhortation only — is something called the Alcoholic Foundation, which has offices at 415 Lexington Avenue, New York City. For a foundation it acts queerly about money; much of its time is consumed in turning down proffered donations and bequests. One tradition is that AA must be kept poor, as money represents power and the society prefers to avoid the temptations which power brings. As a check on the foundation itself, the list of trustees is weighted against the alcoholics by eight to seven. The nonalcoholic members are two doctors, a sociologist, a magazine editor, a newspaper editor, a penologist, an international lawyer and a retired businessman.

Preserving the principle of anonymity is one of the more touchy tasks of the foundation. Members are not supposed to be anonymous among their friends or business acquaintances, but they are when appearing before the public—in print or on radio or television, for example—as members of Alcoholics Anonymous. This limited anonymity is considered important to the welfare of the movement, primarily because it encourages members to subordinate their personalities to the principles of AA There is also the danger that if a member becomes publicized as a salvaged alcoholic he may stage a spectacular skid and injure the prestige of the society. Actually, anonymity has been breached only a few dozen times since the movement began, which isn’t a bad showing, considering the exhibitionistic nature of the average alcoholic.

By one of the many paradoxes which have characterized its growth, Alcoholics Anonymous absorbed the “keep it poor” principle from one of the world’s wealthiest men, John D. Rockefeller, Jr. The society was formed in 1935 after a fortuitous meeting in Akron between a Wall Street broker and an Akron surgeon, both alcoholics of long standing. The broker, who was in Akron on a business mission, had kept sober for several months by jawing drunks — unsuccessfully — but his business mission had fallen through and he was aching for a drink. The surgeon, at the time they got together, was quite blotto. Together, over a period of a few weeks, they kept sober and worked out the basic AA technique. By 1937, when they had about fifty converts they began thinking, as all new AAs will, of tremendous plans—for vast new alcoholic hospitals, squadrons of paid field workers and the literature of mercy pouring off immense presses. Being completely broke themselves, and being promoters at heart, as most alcoholics are, they set their sights on the Rockefeller jack pot.

Rockefeller sent an emissary to Akron to look into the phenomenon at work there, and, receiving a favorable report, granted an audience to a committee of eager-eyed alcoholics. He listened to their personal sagas of resurrection from the gutter and was deeply moved; in fact, he was ready to agree that the AAs had John Barleycorn by the throat. The visitors relaxed and visualized millions dropping into the till. Then the man with the big money bags punctured the vision. He said that too much money might be the ruination of any great moral movement and that he didn’t want to be a party to ruining this one. However, he did make a small contribution—small for Rockefeller — to tide it over for a few years, and he got some of his friends to contribute a few thousand more. When the Rockefeller money ran out, AA was self-supporting, and it has remained so ever since.

Although AA remains in essence what it has always been, many changes have come along in late years. For one thing, the average age of members has dropped from about forty-seven to thirty-five. The society is no longer, as it was originally, merely a haven for the “last gaspers.” Because of widespread publicity about alcoholism, alcoholics are discovering earlier what their trouble is.

As AA has achieved wider social acceptance, more women are coming in than ever before. Around the country they average 15 per cent of total membership; in New York, where social considerations never did count for much, the AAs are 30 per cent women. The unmarried woman alcoholic is slow to join, as she generally gets more coddling and protection from her family than a man does; she is what is known in alcoholic circles as a “bedroom drinker.” The married-woman alcoholic has a tougher row to hoe. The wife of an alcoholic, for temperamental and economic reasons, will ordinarily stick by her erring husband to the bitter end. The husband of an alcoholic wife, on the other hand, is usually less; a few years of suffering are enough to drive him to the divorce court, with the children in tow. Thus the divorced-woman AA is a special problem, and her progress in sobriety depends heavily upon the kindliness shown her by the other AA women. For divorcees, and for other women who may be timid about speaking out in mixed meetings, special female auxiliary groups have been formed in some communities. They work out better than a cynic might think.

Another development is the growth of the sponsor system. A new member gets a sponsor immediately, and it is the function of the sponsor to accompany him to meetings, to see that he gets all the help he needs and to be on call at any time for emergencies. As an emergency usually amounts only to an onset of that old feeling for a bottle, it is customarily resolved by a telephone conversation, although it may involve an after-midnight trip to Ernie’s gin mill, whither the neophyte has been shanghaied by a couple of unregenerate old drinking companions. As the membership of AA cuts through all social, occupational and economic classes, it is possible to match the sponsor with the sponsored, and this seems to speed up the arrestive process.

During the past decade or so, the society, whose original growth was in large cities, has strongly infiltrated the grass-roots country. Its arrival in this sector was delayed largely because of the greater stigma, which attaches to alcoholism in the small town. Because of this stigma and the effect it has on his business, professional or social standing, the small-town alcoholic, reveling in his delusion that nobody knows about his drinking—when actually it is the gossip of Main Street — takes frequent “ vacations” or “business trips” if he can afford it. He or she — the banker, the storekeeper, the lawyer, the madam president of the garden club, sometimes even the clergyman — is actually headed for a receptive hospital or clinic in the nearest large city, where no one will recognize him.

The pattern of small-town growth begins when the questing small-towner seeks out the big-city AA outfit and its message catches on with him. To his surprise, he finds that half a dozen drinkers in towns near his own have also been to the fount. On returning to his home, he gets in touch with them and they form an inter-town group; or there may be enough drinkers in his own town to begin a group. Though there is a stigma even to getting sober in small towns, it is less virulent than the souse stigma, and word of the movement spreads throughout the county and into adjoining counties. The churches and newspapers take it up and beat the drum for it; relatives of drunks, and doctors who find themselves unable to help their alcoholic patients, gladly unload the problem cases on AA, or AA is glad to get them. The usually intra-fellowship quarrel over who is going to run the thing inevitably develops and there are factional splits, but the splits help to spread the movement, too, and all the big quarrels soon become little ones, and then disappear.

Nowhere is Alcoholics anonymous carried on with more enthusiasm than in Los Angeles. Unlike most localities, which try to keep separate group membership small, for easier handling, Los Angeles likes the theatrical mass meeting setting, with 1000 or more present. The Los Angeles AAs carry their membership as if it were a social cachet and go in strongly for square dances of their own. Jewelry bearing the AA monogram, though frowned upon elsewhere, is popular on the Coast. After three months of certified sobriety a member receives a bronze pin; after one year he is entitled to have a ruby chip inserted in the pin and, after three years, a diamond chip. Rings bearing the AA letters are widely worn, as well as similarly embellished compacts, watch fobs and pocket pieces.

Texas takes AA with enthusiasm too. In the ranch sector, members drive or fly hundreds of miles to attend AA square dances and barbecues, bringing their families. In metropolitan areas, such as Dallas-Fort Worth — there are upwards of a dozen oil-millionaire members here — fancy club quarters have been established in old mansions and the brethren and large families rejoice, dance, and drink coffee, and soda pop amid expensive furnishings. One Southwestern group recently got its governor to release a life-termer from the state penitentiary for a weekend, so that he could be the guest of honor of the group. “We have a large open meeting,” a local member wrote a friend elsewhere in the country, “and many state and country officials attended in order to hear from Herman (the lifer) had to tell about AA within the walls. They were deeply impressed and very interested. The next night I gave a lawn party and buffet supper in Herman’s honor, with about 50 AAs present. This was the first occasion of this kind in the state and to our knowledge the first in the United States.”

Some AAs believe that this group carried the joy business too far. Others think that each section of the country ought to manifest spirit in its own way; anyway, that is the way it usually works out. The Midwest is businesslike and serious. In the Deep South the AAs do a certain amount of Bible reading and hymn singing. The Northwest and the upper Pacific Coast help support their gathering places with the proceeds from slot machines. New York, a catchall for screwballs and semi-screwballs from all over, is pious about gambling, and won’t have it around the place. New England is temperate in its approach, and its spirit is characterized by the remark of one Yankee who, writing a fellow AA about a lake cottage he had just bought, said, “The serenity hangs in great gobs from the trees.”

The serene mind is what AAs the world over are driving toward, and an epigrammatic expression of their goal is embodied in a quotation which members carry on cards in their wallets and plaster up on the walls of their meeting rooms: “God grant me the serenity to accept things I cannot change, courage to change things I can, and wisdom to know the difference.”

Originally thought in Alcoholics Anonymous to have been written by St. Francis of Assisi, it turned out, on recent research, to have been the work of another eminent non-alcoholic. Dr. Reinhold Nieburh, of Union Theological Seminary. Dr. Niebuhr was amused on being told of the use to which his prayer was being put. Asked if it was original with him, he said he thought it was, but added, “Of course, it may have been spooking around for centuries.”

Alcoholics Anonymous seized upon it in 1940, after it had been used as a quotation in the New York Herald Tribune. The fellowship was late in catching up with it; and it will probably spook around a good deal longer before the rest of the world catches up with it.

“The Drunkard’s Best Friend” by Jack Alexander, The Saturday Evening Post, April 1, 1950

More on Alcoholics Anonymous:

“Alcoholics Anonymous”

by Jack Alexander

“A Skeptical Journalist”

by Jack Alexander

Bill W’s Last Drink

On December 11, 1934, William Griffith Wilson took his last drink of alcohol. He didn’t know it at the moment, nor did he know he was about to start a new chapter in his life, and the lives of thousands of Americans.

In the aftermath of his last bout of drinking, Wilson once again entered a detoxification program. He was hoping this time he could end the 13-year struggle with alcohol that had destroyed his career and his health.

He soon realized that simply “drying out” in a sanitarium wouldn’t help. But it was during this hospitalization that he got the inspiration for a better program. Between 1935 and ’36, he worked with a physician (and fellow alcoholic) to create a new approach to ending their addiction to drink. Together they created a program called Alcoholics Anonymous, which Wilson described in a book that he wrote under the pseudonym of “Bill W.”

Six years passed. Two thousand Americans had joined the program and many had recovered sobriety and sanity in their lives. But the program was still relatively unknown, and had never promoted itself to the public. Then, in March, the Post published “Alcoholics Anonymous” by Jack Alexander and introduced this unusual program to the rest of America.

A.A. was unusual for several reasons, as Alexander pointed out. First, it threw out the traditional thinking about alcoholism, which regarded it as a moral failing, a mental weakness, or a personal choice. Rather it defined the condition as a disease, which could never be cured but could be successfully managed. The program’s members told Alexander—

There is…no such thing as an ex-alcoholic. If one is an alcoholic—that is, a person who is unable to drink normally—one remains an alcoholic until he dies, just as a diabetic remains a diabetic. The best he can hope for is to become an arrested case.

Another unusual aspect was the program’s emphasis on personal responsibility and spirituality. A.A. required the alcoholic to be fully committed and willing to seek guidance and strength from some “higher power.”

The program will not work…with those who only “want to want to quit,” or who want to quit because they are afraid of losing their families or their jobs. The effective desire, they state, must be based upon enlightened self-interest; the applicant must want to get away from liquor to head off incarceration or premature death. He must be fed up with the stark social loneliness which engulfs the uncontrolled drinker and he must want to put some order into his bungled life.

If he applies to Alcoholics Anonymous, he is first brought around to admit that alcohol has him whipped and that his life has become unmanageable. Having achieved this state of intellectual humility, he is given a dose of religion in its broadest sense. He is asked to believe in a Power that is greater than himself, or at least to keep an open mind on that subject while he goes on with the rest of the program.

Another unique feature was the absence of ministers, doctors, or other professionals. The program was run by alcoholics, who knew all the dodges, excuses, and denials that applicants would bring to the program.

There is no specious excuse for drinking which the trouble shooters of Alcoholics Anonymous have not heard or used themselves. When one of their prospects hands them a rationalization for getting soused, they match it with half a dozen out of their own experiences.

But of all the remarkable aspects of the program, the most important was its success. Over the years, thousands of Americans were able to reclaim their lives, their families, and their careers through the program.

In 1950, when Alexander wrote a follow-up article, the program had grown to 3,000 groups with 90,000 members.

Ninety thousand persons, roaring drunk or roaring sober, are but a drop in the human puddle, and they represent only a generous dip out of the human alcoholic puddle. [Yet] to anyone who has ever been a drunk or who has had to endure the alcoholic cruelties of a drunk —and that would embrace a large portion of the human family — 90,000 alcoholics reconverted into working citizens represent a massive dose of pure gain. In human terms, the achievements of Alcoholics Anonymous stand out as one of the few encouraging developments of a rather grim and destructive half century.

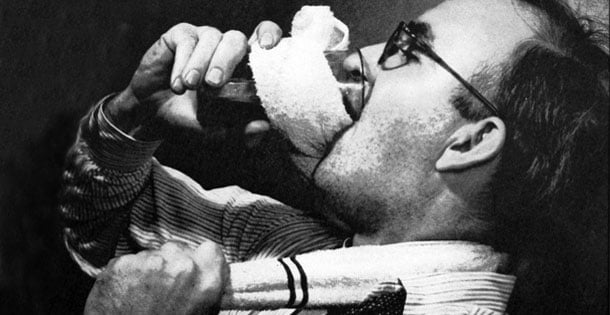

(The top photo, from the Alexander’s 1941 article, illustrated how some member of A.A. managed to continue drinking when their hands were shaking violently: “[They tied] an end of a towel about a glass, looping the towel around the back of the neck and drawing the free end with the other hand, pulley fashion, to advance the glass to the mouth.”)

Here are the pages of the Post article as they appeared in 1941: