The 5 Biggest Bailouts Ever

They say the business of America is business, but occasionally the only thing left to help a business is America. On certain occasions, our government has politely stepped away from a generally hands-off attitude and intervened to save companies or industries whose dissolutions might have dire, wide-ranging consequences for the economy. Forty years ago this week, President Jimmy Carter led a bailout of Chrysler, a move that allowed it to survive (before being bought out down the road). The Chrysler bailout wasn’t the biggest ever, nor would it be the last; here are five more of the biggest bailouts in American history.

1. The American Automobile Industry

The Great Recession of 2008 threw the world into financial upheaval. Automobile sales slumped dramatically, which led to Chrysler (yes, again) and General Motors asking for emergency loans. With bankruptcy looming for both GM and Chrysler by 2009, the governments of both the United States and Canada intervened, supplying $85 billion that enabled the two companies to restructure by filing for Chapter 11. After the proceedings, GM was able to make a new initial public offering for stock in 2010, and returned to profitability. Chrysler was eventually purchased by Fiat and officially merged with that company in 2014.

Was It Successful?: For the most part, yes. Chrysler’s ongoing success ended up being dependent on the merger with Fiat. However, GM is, as of 2019, the 13th largest U.S. corporation by revenue, according to Forbes. At the time of the bailout, none other than Mitt Romney, whose father ran American Motors at one time, said that the action by President Barack Obama would effectively end the American auto industry. One of them was right; coincidentally, it was the guy that beat Romney in the 2012 election.

2. Fannie Mae & Freddie Mac

The Federal National Mortgage Association (or FNMA, nicknamed Fannie Mae) and Federal Home Loan Mortgage Corporation (or FHLMC, nicknamed Freddie Mac) were created by acts of Congress to broaden the secondary market for mortgages. Fannie and Freddie expanded the pool of money available to back mortgages and home loans by allowing the companies to buy mortgages, bundle them, and sell them as securities to investors. However, a number of factors in the late 2000s, including the sub-prime mortgage crisis, caused the value of the two entities to drop by 90 percent in 2008. On September 7, 2008, both companies went under the conservatorship of the Federal Housing Finance Agency; to keep the two above water and protect the ability of people to secure home loans, the U.S. Treasury dished out $116 billion to Fannie Mae and $71 billion to Freddie Mac. By 2018, the two companies together had paid back the Treasury more than $300 billion combined.

Was It Successful?: Like GM, Fannie Mae bounced back in a big way; in 2018, they were number 19 on the Fortune 500. Freddie Mac entered the same list at 38. There’s been discussion under the current presidential administration about letting the companies out of conservatorship, but it probably won’t happen until 2022.

3. AIG

American International Group, Inc. is an insurance and finance giant. In a tune that’s beginning to sound familiar, the company took on billions of dollars of risk associated with mortgages in the early 2000s. When the Great Recession kicked in, not only did AIG have to pay out claims, they had to cover their own huge losses. By late 2008, the government stepped in with $180 billion in bailout money, partially because of the fear of a ripple effect that a collapsing AIG would cause for other financial institutions and partners at an already precarious moment. That action earned AIG a “Too Big to Fail” tag, a term that had been popularized after 1984 efforts to save the Continental Illinois bank. (The phrase subsequently became the title of Andrew Ross Sorkin’s book about the financial crisis and later HBO film adaptation.) The Treasury Department sold the last of its AIG stock in 2012.

Was It Successful?: Yes. As the company recovered, investor Carl Icahn (known for everything from “corporate raiding” to advising Donald Trump) called them “too big to succeed” in 2015, advocating for the break-up of the company into smaller units. Icahn eventually got a seat on the board. In 2017, the company reorganized into three distinct units, and is the 87th largest company in the world.

4. The Airline Industry

In the wake of the September 11, 2001 attacks, the U.S. airline industry was thrown into turmoil. In addition to the obvious human cost, the loss of four planes and personnel, as well as the losses incurred by several days of shuttered air travel within the country, caused the industry to lose millions. Additionally, a decline in tickets sales occurred as the airlines took to the skies again, due in part to travelers’ anxieties about air travel following the events. In response, Congress quickly passed The Air Transportation Safety and System Stabilization Act which created the office of the Air Transportation Stabilization Board in the Department of the Treasury. They were able to issue $10 billion in loan guarantees to help the airlines in the aftermath. Over the next two years, seven airlines received loans of just over a billion dollars each. A number changes came out of these precarious years, including the eventual mergers of America West and U.S. Airways into American Airlines, the absorption of Frontier by Republic Airways, and the closures of ATA (American Trans Air), Evergreen International, Aloha Airlines, and World Airways.

Was It Successful?: American Airlines is now the world’s largest. They were posting profits as recently as the second quarter of 2019.

5. The Chrysler Bailout of 1980

After the Oil Crisis of the early 1970s, Americans started to favor smaller cars; that wasn’t Chrysler’s forte at the time, and they struggled. After Lee Iacocca took over toward the end of the decade, he went to the feds for help. The response was The Loan Guarantee Act, which lent the company $1.5 billion, provided that they also secure $2 billion more from outside the government. That helped them right the ship, and the loans were repaid in 1983; that same year, Chrysler debuted the minivan with the Dodge Caravan/Plymouth Voyager, ensuring both the survival of the country and the proliferation of youth soccer.

Was It Successful?: Yes. Right up until the Great Recession of 2008.

Economists and politicians continue to debate the pros and cons of bailouts. It’s easy to see the immediate benefits when they help companies recover and enable workers to keep their jobs. However, one also sees the danger inherent in having a system that can decide which business is saved and which is allowed to collapse. Since the only thing certain in an economy is uncertainty, it’s likely that we’ll have an all-new bailout to debate when we least expect it.

Featured image: Shutterstock.

The Case of the Missing Prosperity: An Economic Mystery from 1952

Back in 2008, when America’s economy began crumbling, financial experts swarmed into the media spotlights to explain what was happening. “High-risk investing by deregulated banks,” they said, and “collateralized debt obligations.” Few people understood what they were talking about, but we had an explanation, and that was better than nothing.

Two years on, the economy continues to weaken, unemployment grows, the average American’s purchasing power drops, mortgage defaults rise, and the American Dream seems smaller and more fragile than ever. Experts talk of “credit default swaps” and a “Troubled Asset Relief Program,” but the problem seems impossible to pin down.

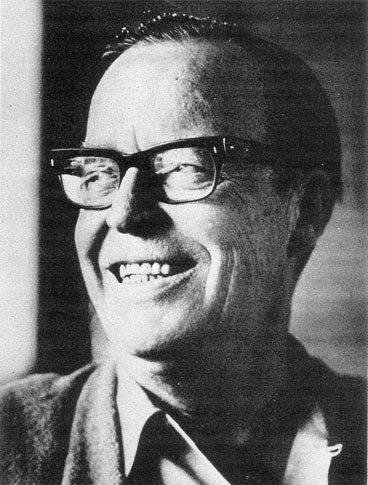

The birthday of Peter Drucker, November 19, is a good reminder that experts in management and economics haven’t always been incomprehensible. Drucker, the pioneer of management consulting, always managed to discuss the world of finance clearly and readbly, without oversimplifying.

Drucker was a frequent Post contributor in the 1940s and ’50s, when he was starting to advise major U.S. corporations on management policy and corporate structure. He saw trends long before they became obvious to American businesses: decentralizing, outsourcing, even the rise of the “information economy.” (What Drucker meant by “outsourcing” was the practice of hiring skilled workers from contractor agencies, not the newer meaning of exporting of American jobs en masse to cheap labor markets overseas.)

When he died at age 96, he was widely considered as a pioneer in management, and a man who was usually proved right.

To honor his birthday, I could have excerpted any of his incisive, highly readable studies of the German and Russian economies during World War II, or his thoughts about profits and inflation in the U.S. economy. Instead, I have chosen a historical mystery with unintended poignance: his 1952 article, “Look What’s Happened to Us!”

The subhead for the article prepares the reader for some unusual content:

Our kids have a better chance of success than ever before— yet shocked Europeans look at how we have changed and say, “This is worse than socialism!”’

Drucker, though, is no sensationalist. His article describes how the American economy of 1952 has become a powerful force for democracy by promoting wealth AND equality.

If you are an American and over twenty-five you have taken part, knowingly or unknowingly, in “one of the greatest social revolutions in history.” This summing up of the last quarter century of American history does not come from a Hollywood press agent or from a Fourth of July orator. It came, a few months ago, from the National Bureau of Economic Research, for the last twenty-five years the country’s leading student of long-range economic trends, and an outfit so ultra-scholarly, austere and publicity-shy that the most extreme term it had ever used before was a restrained and barely audible “statistically significant.” The development that provoked such unscholarly language was the change in the distribution of income during the last generation. It is indeed an amazing change.

The income gap between the rich and the poor, Drucker states, is shrinking.

More than half of the nation’s families now have a middle-class income—as against a quarter of the population fifty years ago… The further down the income scale we go, the greater, by and large, has been the rise. The 1900 dollar bought about three times what the 1951 dollar buys [but] the yearly income of the factory worker has gone up six-fold, from around $500 in the days of Andrew Carnegie and John D. Rockefeller, to $3,000 or more today.

The increasing wealth of workers is part of a revolution in the idea of capitalism.

We have produced a capitalist system in which ownership rests with the mass of the people. Individual horizons have steadily broadened—indeed, the progress toward equality of opportunity has, as befits a free country, been at least as fast as that toward equality of income or wider distribution of wealth.

The very term “capitalism” has come to mean something new. Formerly it expressed an all-but-complete divorce between the good of business and the good of the economy—if not an irreconcilable conflict. We now believe that there must be harmony between the ends of business and the good of society in the interest of both.

An illustration of this new idea is in business’ new concept of people. Fifty years ago the emphasis was on labor as a cost; today it is increasingly on human beings as a resource—and the scarcest, most important and most productive resource, at that.

Two years ago, well before Korea, the president of one of the largest steel companies asked some of his vice-presidents to figure out how much additional steelmaking capacity the company should build. In the letter in which be gave them this job, he said, “Do not start your figuring with the question of what capacity would be most profitable for our company. Start with the question how much steel the country will require to be strong and prosperous, and then work back to find out how much of that total our company should aim to provide.”

A visiting French steelmaker who chanced to see the letter was quite shocked. “This is worse than socialism,” he said. And, indeed, the approach would have appeared as eccentric to the men who ran the same steel company twenty-five years ago, and would have been hardly even conceivable to the men who ran it fifty years ago.

This philosophy rests upon the conviction, buttressed by experience, that the only line of action that will pay in the long run is that which serves American society as well as their own company. Socially irresponsible action… simply does not pay.

We believe that the businessman must act responsibility—not just because his own business aim demand it. We no longer believe that there is a cleavage between the demands a business makes on a person as a businessman and the demands society makes on him as a citizen.

We are learning fast that the human being is the most important, the most productive and also the scarcest economic resource… During the last ten years or so it has become almost a commonplace in American business that the job of management is the leadership of people rather than the working of property.

It has always been a distinct trait of American business, and of American business alone, that it believed in the opportunity of the man at the bottom to rise to the top. But it is only now that American business is going out systematically to find the men of ability, initiative and ambition in plant or office, to train them and to give them a chance to grow and to advance.

Peter Drucker was neither an idealist nor an optimist. He saw the problems of modern business more clearly than many of his contemporaries. Business executives paid him large sums of money for his penetrating assessments. Yet here he is, explaining how American business has become socially responsible, and inspired by a sense of ethical pragmatism.

Was 1952, in fact, the year that corporations began balancing social good with stockholder returns? Did Drucker really have evidence for his claims of corporate altruism? If so, how did social trends turn around so completely?

We like to believe that life in America generally gets better over time: Each generation enjoys a little more prosperity and freedom than its predecessor. If Drucker’s picture is accurate, businesses and workers in America have been passing through a long decline.