The People Nobody Wants: The Plight of Japanese-Americans in 1942

Originally published May 9, 1942

On the fateful day that Lt. Gen. John L. De Witt, chief of the Western Defense Command, ordered the removal of all persons of Japanese blood from the Pacific Coast Combat Zone, chunky little Takeo Yuchi, largest Japanese farmer in “the Salad Bowl of the Nation,” California’s Salinas Valley, was wrangling over the telephone with a produce buyer in San Francisco.

“That fellow purchases for the Navy,” he said, slamming down the phone. “He wants me to grow more Australian brown onions because the Navy needs them. The Army tells us to evacuate our farms right now. Just where do we stand, anyway?”

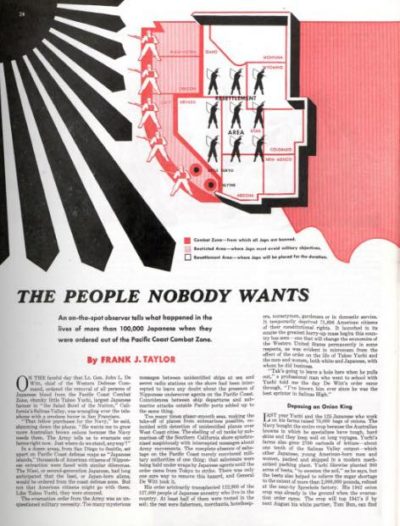

In a dozen areas, from San Diego to Seattle, set apart on Pacific Coast defense maps as “Japanese islands,” thousands of American citizens of Nipponese extraction were faced with similar dilemmas. The Nisei, or second-generation Japanese, had long anticipated that the Issei, or Japan-born aliens, would be ordered from the coast defense zone. But not that American citizens might go with them. Like Takeo Yuchi, they were stunned.

At least half of the 112,905 people of Japanese ancestry affected by the order were rooted in the soil; the rest were fishermen, merchants, hotelkeepers, nurserymen, gardeners, or in domestic service. It temporarily deprived 71,896 American citizens of their constitutional rights. It launched in its course the greatest hurry-up mass hegira this country has seen.

“Tak’s going to leave a hole here when he pulls out,” a professional man who went to school with Yuchi told me the day De Witt’s order came through. “I’ve known him ever since he was the best sprinter in Salinas High.”

Yuchi’s own family, consisting of his alien mother, his Salinas-born wife, his 8-year-old daughter, 6-year-old son, and a baby daughter, is an average California-Japanese household. His wife’s brother, Hideo Abe, is in the Army. His younger brother, Masao, was called in by the local draft board for his physical examination the day I was there. Of the 21,000 Japanese families on the Pacific Coast, one in every five has contributed a son to the Army.

“Well, are you going to go voluntarily or wait until the Army evacuates you?” I asked.

“It’s a tough one to figure out,” Yuchi replied. “I’m American. I speak English better than I do Japanese. I think in English, not Japanese.”

After leaving the Yuchi household, I called on another Nisei, Dr. Harry Y. Kita, a dentist. Prior to Pearl Harbor, Kita, a University of California graduate, enjoyed a thriving practice. Half of the patients who sat in his three chairs were whites. Since then, most of them had been from the Japanese community. “I haven’t much practice left,” said Kita, with a hearty but forced laugh. “I understand why it is,” he continued. “I feel American. I think American. I talk American. My only connection with Japan is that I look Japanese.”

“Could you tell a good Japanese from a bad one?” I asked him.

“No more than you could,” he replied. “But if I knew one who was disloyal to this country, you can bet I’d turn him in.”

Dorothea Lange

Vegetable Wars

From white vegetable growers I heard the other side of the story. The Salinas Vegetable Grower-Shipper Association had just published a brochure titled NO JAPS NEEDED to counteract a widespread impression that Californians would go hungry if the Japanese truck gardeners were removed. The dislike of the militant Grower-Shipper Association for the valley’s Japanese farmers is an old and bitter one. The association is composed of a few score large-scale white growers who lease lands, produce lettuce, carrots, and other fresh vegetables the year round in the Salinas, Imperial, and Salt River Valleys for the Eastern markets. … At one time the lettuce growers, like the sugar-beet growers, depended upon Japanese for field labor. As the Japanese, one by one, became farmers in their own right, and competitors, their places in the field were taken by Mexican or Filipino labor. White men and women, largely Oklahomans, handled the trimming, icing, and crating in the packing plants, but they were never able to endure the back-breaking stoop work in the fields. Only the short-legged Japs could take that.

Shortly after December 7, the association dispatched its managing secretary, Austin E. Anson, to Washington to urge the federal authorities to remove all Japanese from the area. “We’re charged with wanting to get rid of the Japs for selfish reasons,” Anson told me. “We might as well be honest. We do. It’s a question of whether the white man lives on the Pacific Coast or the brown men. They came into this valley to work, and they stayed to take over. … If all the Japs were removed tomorrow, we’d never miss them in two weeks, because the white farmers can take over and produce everything the Jap grows. And we don’t want them back when the war ends, either.”

The Japanese-American loyalty creed, to which all Nisei publicly subscribe, is about to get its first real test, particularly these portions of it: “… I am firm in my belief that American sportsmanship and attitude of fair play will judge citizenship and patriotism on the basis of action and achievement, and not on the basis of physical characteristics. … Although some individuals may discriminate against me, I shall never become bitter or lose faith, for I know that such persons are not representative of the majority of the American people. …” In such a test, the tolerance of the new host states will also feel the fire which has been ignited by the obvious requirements of a stern military emergency.

—“The People Nobody Wants,” Frank J. Taylor,

May 9, 1942

This article is featured in the May/June 2017 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Also read Unwanted: A Teenage Memoir of Japanese Internment from the May/June 2017 issue of The Saturday Evening Post.

Are You Smart Enough to Be a Citizen?

Are you smart enough to be a citizen? That question was posed 71 year ago by Robert M. Yoder. He realized that democracy in the postwar world needed well-educated voters.

In the past, he wrote, there had been little demand for Americans to be well informed. The average American “didn’t have to think hard four times in his lifetime.” The country enjoyed a steady run of breaks that allowed it to “muddle along pretty well even with a population of sleepwalkers.”

But the postwar world brought complicated questions that required thoughtful answers: How could the U.S. feed the starving people of Europe and Asia; how would we face the communist threat; and what were we supposed to do with this mysterious new creature, the International Monetary Fund?

The problems were both “terrifically important and terrifically dull. They may kill, but they don’t interest.” Americans would need to study hard, Yoder wrote, “and it is dry stuff.”

If smart voters were needed in 1946, they’re certainly in demand now. International hacking conspiracies, intricate healthcare proposals, and thorny foreign entanglements are the types of complex problems that average citizens are required to comprehend today. So how have American citizens, and voters, done in educating themselves? Not very well, according to the reports.

In 2010, a report from Yale University uncovered these discouraging facts:

- fewer than 50% of Americans had read any fiction or poetry in the preceding year

- only 57% had read any nonfiction work

- 49% of adults didn’t know how long it takes the Earth to circle the sun

- more than 50% of Americans didn’t know Genesis is the Bible’s first book

- 10% believed Joan of Arc was Noah’s wife

In 2011, Newsweek asked 1,000 American citizens to take the citizenship test. Nearly 40% failed.

- 29% couldn’t name the vice president

- 73% couldn’t correctly explain the Cold War

- 44% were unable to define the Bill of Rights

- 6% couldn’t point to Independence Day on a calendar

Just how difficult are the questions?

Before answering that question, note that the “civics test” is only one of four different tests an applicant must pass before citizenship is granted.

Applicants must first be able to speak sufficient English to a U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services officer during an eligibility interview. Next, they must prove an ability to read English by reading aloud one of three sentences correctly. Then they must write out one of three sentences to prove an ability to write in English. Last, they must answer 6 out of 10 questions taken from a list of 100.

Below are 10 questions from the big list. If your citizenship rested on your ability to correctly answer 6 of them, would you be able to vote in the next election? Click here to see the answers.

- What does the Constitution do?

- What do we call the first 10 amendments to the Constitution?

- How many amendments does the Constitution have?

- What is the economic system in the United States?

- Who makes federal laws?

- The House of Representatives has how many voting members?

- We elect a U.S. Senator for how many years?

- Under our Constitution, some powers belong to the states. What is one power of the states?

- What happened at the Constitutional Convention?

- Name one U.S. territory.

Too easy? See all 100 questions.

Featured image: A naturalization ceremony at Grand Canyon National Park, September 24, 2010 (Wikimedia Commons, Grand Canyon National Park via Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic)

50 Years Ago This Week: Abolishing Poverty

This Post editorial by Stewart Alsop from 50 years ago visits a theme that is still a concern today: pervasive poverty, and how to solve it. Alsop examines — and then quickly rejects — the idea of a guaranteed basic income. The debate continues today. Some economists support this extensive safety net, and others dismiss it.

There is a lot Alsop got wrong: he hoped the “Vietnamese War” would end quickly (it didn’t), that public assistance would soon wind up in the ash can (it hasn’t), and that Lyndon Johnson was a cautious politician (he wasn’t). Whether he was right on the dangers of a guaranteed income are still being debated, and are unlikely to be acted upon anytime soon.

After Vietnam — Abolish Poverty?

By Stewart Alsop

Originally published December 17, 1966

WASHINGTON: It may seem foolishly early to be thinking about the end of the war in Vietnam, and what will come after it. But all wars end someday, and already the Government’s leading thinkers are thinking hard and long about the role of Government in the postwar period. To judge from the way they talk, they are thinking more and more seriously about an idea which at first sounds both madly extravagant and faintly ludicrous. The idea is to abolish poverty once and for all by putting a floor under the income of all American citizens. “The way to eliminate poverty is to give the poor people enough money so that they won’t be poor anymore.” says one Government thinker. “If the war ended, we could do that very easily with the money we’re now spending in Vietnam.” The official Government standard for poverty — a four-person, nonfarm family with an income of $3,130 or less per year — now applies to about 17 percent of the total U.S. population. To give these poor people “enough money so that they won’t be poor anymore” would cost somewhere between $12 billion and $15 billion a year — well under the $2 billion a month that Vietnam is now costing. For about two percent of the Gross National Product, in other words, poverty could be abolished in the United States. All American citizens, as a matter of right, would be entitled to a minimum, non-poverty income. And this is where the proposal begins to sound faintly ludicrous. For “all American citizens” would include the drunks and the drug addicts, as well as bad people, immoral people and just plain lazy people. At first blush, it seems wildly unlikely that any administration will risk a proposal that would reward the undeserving poor as well as the deserving poor. No politician wants to be accused of taxing honest citizens in order to subsidize worthless citizens in the purchase of booze or reefers.

And yet the idea of a national minimum-income guarantee is a perfectly serious idea all the same, which is already being seriously debated by serious men. As always in the Johnson Administration, those in official position are reluctant to be quoted by name for fear of infuriating the President. But there are plenty of men still in the Government who agree with such recently departed officials as Joseph Kershaw, provost of Williams College, and Prof. James Tobin of Yale. Kershaw was until recently chief economist with Sargent Shriver’s Office of Economic Opportunity, and Professor Tobin was formerly a member of the Council of Economic Advisers.

Kershaw says confidently that the minimum income guarantee is “the next great social advance…. In the long run it’s inevitable, it’s got to come.” In a recent magazine article which has attracted much attention among Government economists, Tobin argues with conviction that “the upper four-fifths of the nation can surely afford the two percent of Gross National Product which would bring the lowest fifth across the poverty line.”

The basic idea for a minimum-income guarantee was first put forward by Prof. Milton Friedman, who is the chief economic idea-man for — of all people — Barry Goldwater. Friedman called for a “negative income tax,” to be administered by the Internal Revenue Service, to take the place of all federally subsidized relief for the poor. Friedman must have been surprised, and possibly appalled, when his idea was seized upon, and enthusiastically elaborated, by liberal economists like Tobin.

Tobin gives this illustration of how the scheme might work: “The Internal Revenue Service pays the ‘taxpayer’ $400 per member of his family if the family has no income. This allowance is reduced by 33% cents for every dollar the family earns. . . . At an income of $1,200 per person the allowance becomes zero. . . . At some higher income . . . the present tax schedule applies.”

Tobin, Sargent Shriver and others who have interested themselves in the idea point out that although the scheme would cost a lot of money it would save a lot of money too. Direct public assistance to the poor — federal, state and local — now amounts to about $5.5 billion, and the trend is sharply up. The minimum-income guarantee, in theory at least, would consign the present immensely complex system to the ash can. Virtually all economists, left, right and center, seem to agree that the ash can is where that system belongs.

It is a bad system for several reasons. First, there is the “man in the house” rule. The Aid for Dependent Children program is the biggest of the federally subsidized plans. Under the program, as administered in most areas, aid can be provided to a family only if there is no employable male in the household. The result, as Tobin points out, is that “too often a father can provide for his children only by leaving both them and their mother.” He calls this incentive to the disintegration of family life “a piece of collective insanity.”

Moreover, the “means test” tends totally to kill all initiative. The idea of the means test is that a family will get public assistance only to the extent that it cannot pay its own way. In practice, the result is that a poor man who earns $1,000 toward the support of his family doesn’t profit by a penny, since the $1,000 is subtracted from his relief checks. Under the “negative income tax” system, he would keep part of every dollar he earned.

The means tests and other complicated bureaucratic requirements of the present system tend to turn the social workers who administer the programs, willy-nilly, into part-time spies and policemen. In Negro ghettos, hatred for the administrators of the relief programs is almost universal.

There are, of course, plenty of objections to the whole idea of a universal floor under incomes, quite aside from the vast cost. A program with a price tag of $12 billion to $15 billion might crowd out the “structural” programs — preschool education, job training, slum clearance and the like — which are designed to help the poor escape from poverty. “You’d be treating the symptoms of the disease,” says one critic of the idea, “while letting the disease itself get worse and worse.”

Enthusiasts for a minimum-income guarantee counter that a good doctor treats the symptoms as well as the disease. But the deepest and most instinctive opposition to the idea derives from “the Puritan ethic.” By the standards of conventional morality, it is just plain wrong that a man — especially a bad man or lazy man — should be paid money which he had done nothing to earn by the sweat of his brow. This is why, even to many who like the idea, it seems highly unlikely that Lyndon Johnson will ever buy it.

Lyndon Johnson will certainly not buy the idea while the Vietnamese war continues. He is a cautious politician, and he may never buy it, even if the war ends. But Lyndon Johnson is also a man very conscious of his place in history, and the President who abolished poverty in the United States would certainly occupy a rather capacious niche in his country’s history.