The Family Road Trip

If there was ever a time Americans needed a vacation, it was the 1970s. Nearly everyone had a good reason to pack up their station wagon or VW minibus and leave it all behind. The gloomy conclusion to the war in Vietnam had sent morale plummeting, while unemployment and inflation skyrocketed and remained elevated so long that economists had to coin a whole new term for the phenomenon: stagflation.

The pressure of making ends meet also helped push the traditional nuclear family into meltdown. The number of divorces filed in 1975 doubled that of a decade earlier. All things considered, it isn’t surprising that many people, including my parents, decided the best plan was simply to sit out as much of the ’70s as possible at some distant beach, historic battlefield, or theme park.

Despite the flagging economy, Americans continued taking vacations throughout the ’70s in record numbers, if only for a couple of weeks each year. In fact, 80 percent of working Americans took vacations in 1970, compared to just 60 percent two decades earlier. As a result, attendance at national parks, historic sites, and other attractions surged 20 to 30 percent every year until 1976.

To reach these far-off places, my family, like most others, traveled by car. It wasn’t that we enjoyed spending endless hours imprisoned together in a velour-upholstered cell, squabbling over radio stations. It was that we had no other choice.

Air travel had always been too expensive for anyone not named Rockefeller or traveling on the company dime, much less a pair of middle-class parents taking four kids to the beach. Adjusted for inflation, a domestic plane ticket in the ’70s cost two to three times the price of the same ticket today. Given the cost, it shouldn’t be too surprising — and yet still is — that as late as 1975, four in five Americans had never traveled by plane. Not for a weekend getaway to Las Vegas, not to head off to college, not for a once-in-a-lifetime honeymoon in Paris. Never.

Although ordinary joes couldn’t afford a plane ticket, nearly every family could afford a car, often two. If there was one thing America was very good at, it was producing automobiles. Following World War II, American car factories needed only to do some quick retooling to go from churning out airplanes and tanks to cranking out cars faster than ever. And thanks to a booming economy, Americans could afford to buy all those shiny new cars as fast as they rolled off assembly lines. During the 1970s alone, Americans logged 14.4 trillion highway miles.

My family alone was responsible for approximately 1 trillion of the miles logged by travelers in the ’70s. At least that’s how it seemed to me: As the youngest of four kids, I was the one relegated to the backseat, rear window shelf, or rear cargo compartment of a series of fine American automobiles purchased by my father over the course of the decade. Together, we toured the country (well, half of it anyway — we rarely traveled west of the Mississippi) in week-long journeys taken two and sometimes three times a year.

My father was one of those people born with no “stop” gene. He always had to be on the go, always had to be doing something. Even if he was sitting still, his mind was always racing, thinking about the next item on his to-do list: his next sales call, his next round of golf, his next Rotary meeting, his next whatever.

In short, his disposition made him ill suited for 15- to 24-hour road trips. The advent of the 55 mph national maximum speed limit only exacerbated his restlessness. But what really aggravated my father was having to make stops he judged unnecessary — which is to say, any stop at all. If my dad had his way, we wouldn’t have ever stopped — not for meals, not to refill our gas tank, not even for potty breaks.

What really aggravated my father was having to make stops he judged unnecessary — which to say, any stop at all.

My dad couldn’t do much about our need to occasionally refuel — at least, beyond stretching every tankful of gas to its gauge-defying limit. But he could control how often we stopped for meals. His main strategy was to forget meals altogether. As lunchtime approached after a long morning’s drive, he’d click off the radio and announce, “Why don’t we all take a break for a while? Maybe you kids can get a little extra sleep. You’ll want to be rested for the beach tomorrow!” We’d settle into our corners to read magazines, click away on our electronic games, or just doze off, only to awaken hours later with rumbling stomachs.

Finally, one of us would say, “Dad, I’m hungry! When are we stopping to eat?”

“Oh, look at that,” he’d respond, playing dumb. “Did we miss lunch? Well, no point stopping now. We’d just ruin our appetites for dinner!” Then he’d ease into the passing lane just in case any exits appeared.

Though I have little knowledge of such things from personal experience, I’m told some families once even stopped for minutes — maybe an hour! — to enjoy freshly cooked meals — served on actual plates with silverware! — while out on the highways. In fact, one man built an empire preparing such meals for hungry travelers. His name was Howard Deering Johnson.

Johnson inherited his entrepreneurial spirit from his father, who owned a Boston cigar store and export business in the early 1920s. Unfortunately for Johnson, he also inherited the equivalent of more than $100,000 in debt when his father died and left him the foundering business. Quickly concluding that the cigar business might not be the best for striking it rich, Johnson decided to try his hand at another, buying a small drugstore and soda fountain in the Wollaston neighborhood of Quincy, Massachusetts, in 1925.

Business was brisk at the soda fountain, but competition was fierce. To help his business stand out, Johnson decided he needed to offer truly outstanding ice cream — like the kind made by a local pushcart vendor, an elderly German immigrant. Learning the man was contemplating retirement, Johnson paid the handsome sum of $300 for the vendor’s recipe. The secret, Johnson learned, was doubling the typical amount of butterfat and using only natural ingredients. But for Johnson, even that wasn’t enough. He locked himself away in his basement and used a hand-cranked ice cream maker to create and perfect 28 different flavors, a number Johnson believed covered “every flavor in the world.”

Before long, customers were lining up for Johnson’s tantalizing array of frozen treats. He quickly opened another stand at a local beach — it served as many as 14,000 cones in a single day! Leveraging the popularity of his ice cream, Johnson began serving freshly grilled meals as well and soon opened a full-blown restaurant. Besides hamburgers, “frankforts” (as Howard Johnson called his hot dogs), chicken pot pies, and other staples, the menu also included another New England favorite: fried clams. Unlike other restaurants, which served whole clams, Howard Johnson’s prepared and fried only the meaty foot of each clam, calling them “clam strips.” The item became Howard Johnson’s signature dish.

However, just as Johnson was hoping to take advantage of his growing fame by opening another location, the stock market crash of 1929 intervened. Unable to find financing, Johnson hit on the idea of leasing his restaurant’s increasingly famous name and recipes to the owner of an existing restaurant. This location, on the tourist mecca of Cape Cod, also proved fabulously successful. Soon other restaurant owners were clamoring to borrow the Howard Johnson’s name and purchase his food. Howard Johnson had invented franchising.

It wasn’t long before Johnson purchased the exclusive rights to build restaurants in service plazas along the new Pennsylvania Turnpike, Ohio Turnpike, and New Jersey Turnpike. By the late 1970s, Howard Johnson’s controlled more than 1,000 restaurants (under several names) and 500 motor lodges, making it the largest hospitality chain in the world.

If you want to start a food fight, there’s no better way than to declare where to find the world’s best barbecue or proclaim who invented the first drive-through restaurant. In his book The American Drive-In: History and Folklore of the Drive-In Restaurant in American Car Culture, Michael Karl Witzel makes a strong argument that credit for both should go to Texas entrepreneur Jessie G. Kirby and his chain of roadside Pig Stands, the first of which opened along the Dallas–Fort Worth highway in 1921. Declaring “people in their cars are so lazy that they don’t want to get out of them to eat,” Kirby had a brainstorm to employ a fleet-footed staff of order takers. The carhops (so named because the tip-motivated servers would sprint out to hop up on an approaching automobile’s running board) would take food orders right through the customer’s car window. Billed as “America’s Motor Lunch,” the new system launched a craze.

Technically, Kirby’s idea qualified his Pig Stand only as America’s first drive-in restaurant. The first drive-through would come later, and once again Kirby’s Pig Stand would be the originator. In 1931, Pig Stand No. 21 in California simply sawed a window into the wall beside the grill, allowing customers to drive up alongside the building and collect their food directly from the cooks who prepared it. It was a classic example of eliminating the middleman.

And so ends the debate about who invented the drive-through window, right? Well, don’t go pulling off just yet. Other sources claim the idea was conceived by a young ginger-haired entrepreneur named Sheldon “Red” Chaney, who purchased a small gas station along Route 66 in Springfield, Missouri, in 1947. After spending 16 hours a day pumping gas and observing customers, Red concluded two things: one, he didn’t want to spend the rest of his life pumping gas, and two, people hate getting out of their cars.

Eating at McDonald’s fit our modest travel budget. After all, the restaurant was cheap, and, well, so was my dad — at least when it came to food.

The Chaneys decided to get out of the business of fueling cars and into the business of feeding motorists. Redecorating their station on a shoestring, Red and his wife Julia covered the dining room’s tables in red-checkered tablecloths and topped each with a button-spigot Coleman cooler and stack of paper cups so diners could dispense their own water. But the couple’s most radical idea was adding a small window in the building’s west wall, allowing drivers to pull up and order food right from their cars.

The drive-through window prompted cars to line up around the building. Eventually Red installed an intercom system so drivers could dictate orders before advancing to the window to collect their food. Voilà! Red’s Giant Hamburg became the first modern fast-food drive-through restaurant.

Though McDonald’s restaurants had been around since the 1940s, the chain didn’t introduce its first drive-through window until 1975. The McDonald’s store in Sierra Vista, Arizona, was located just down the road from the Fort Huachuca military base, making it a popular lunch stop for soldiers. But military rules at the time prohibited enlisted personnel from exiting civilian vehicles dressed in fatigues. To accommodate the soldiers, the franchisee installed a drive-through window. Soon, the only ones dealing with issues of fatigue were the fry cooks scrambling to fill orders, and other franchisees began lobbying McDonald’s headquarters for permission to add their own. By 1980, McDonald’s was collecting $6.2 billion from 6,200 stores. More than half of that cash would be handed over through drive-through windows.

My dad didn’t care how it had all happened. He was just happy it happened at all. Finally, he had a means to put an end to his family’s incessant — unreasonable, he might argue — demands to eat more than once a day while on the road.

Of course, the explosion of McDonald’s restaurants and drive-through windows along the highways only solved the problem of quickly feeding the family. Inevitably, with six people in our car, at least one of us would also have to use the restroom. To complete both tasks with maximum efficiency, my father devised a plan that my family, after regular and rigorous practice, eventually executed to perfection. The goal was simple: keep the car’s wheels moving forward at all times. Prior to getting into the drive-through line, my father would take everyone’s food orders and pull up along the side entrance. Then we’d sprint to the restrooms while Dad eased the car ahead to place our order.

At the time, McDonald’s goal was to provide each drive-through customer’s order within 50 seconds. Factoring in a few additional moments for my father to pause — not stop! — while drivers ahead of him ordered, we had about 90 seconds to go to the bathroom and dash out the door to intercept our passing car.

Aside from all else, my family genuinely enjoyed McDonald’s food. It wasn’t fancy, but it was satisfying and predictable. A McMuffin in Milwaukee tasted the same as the one in Memphis; a Big Mac in Burlington was as big as the one in Baton Rouge. Such consistency was an enormous draw for families like mine while out exploring America — it was a familiar taste of home in places that seemed a world away.

Most important, eating at McDonald’s fit our modest travel budget. After all, the restaurant was cheap, and, well, so was my dad — at least when it came to “discretionary” expenditures such as food. Yet even as inexpensive as McDonald’s was, Dad found ways to trim the tab further. If three of us wanted our own regular-size Coke, he’d instead order one large Coke costing half the price and ask for three complimentary kiddie cups. Indeed, long before McDonald’s introduced the super-size concept, my father came up with “shrink-a-size.” If Dad believed one of us had placed an order that exceeded our appetite, he’d simply scale it back. Hence, many an optimistically ordered Big Mac became a less-than-enthusiastically received regular hamburger. We discovered these arbitrary changes too late. It was only after we were at cruising speed and far past any turnarounds that he’d begin distributing the disappointment.

When it came to deciding what and how much food we’d get in a trip to the drive-through, my dad was — in the most literal sense of the phrase — always in the driver’s seat. It wouldn’t be until I had my own driver’s license that I received exactly what I ordered at a McDonald’s drive-through.

Richard Ratay graduated from the University of Wisconsin with a journalism degree and has worked as an award-winning advertising copywriter for 25 years.

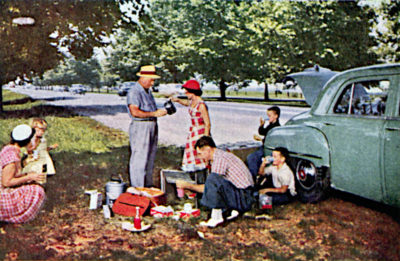

Featured image: PictureLux/The Hollywood Archive/Alamy Stock Photo.

This article is featured in the July/August 2019 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Tylenol’s Modern Spin on ‘Freedom from Want’

I immediately loved the concept for the Tylenol spot, its message spoke to me — it is current and relevant. Taking my grandfather’s painting Freedom from Want, which he painted in 1943, and cleverly bringing that image of family togetherness and celebration into 2015 by reflecting it through three different American families — one African-American, another Asian, and also two moms with their happily extended family. What better way to visually tell the story of how our definition of family is expanding and ever changing? Yet our concept of family remains the same; it is the love and the celebration of that love that connects us all, regardless of race, sexuality, or any other difference. Norman Rockwell’s painting is a timeless reminder of what is most important.