Considering History: Does America Owe Its Existence to France and Morocco?

This series by American studies professor Ben Railton explores the connections between America’s past and present.

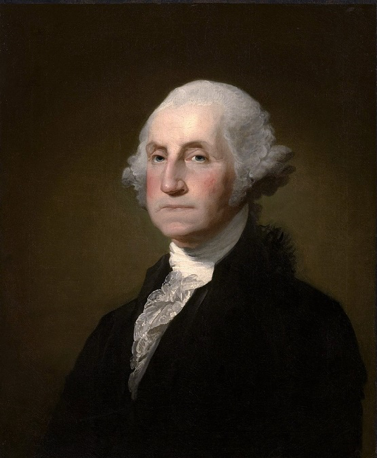

Those seeking to advance arguments for American isolationism have long found clear support in a foundational national text: George Washington’s “Farewell Address,” originally published in the American Daily Advertiser in September of his final year as president (1796). Washington’s piece, co-written by James Madison and Alexander Hamilton, moves through a series of topics, but features a substantial concluding section that warns against “foreign entanglements” and supports an isolated stance in world affairs. “Our detached and distant situation invites and enables us to pursue a different course,” Washington argues. “Why forego the advantages of so peculiar a situation? Why quit our own to stand upon foreign ground? … It is our true policy to steer clear of permanent alliances with any portion of the foreign world.”

While Washington was responding to the specific contexts of late 18th century European conflicts, his remarks also highlight the dangers of becoming too tied to any other nation’s political or global fortunes. But if we emphasize this one document too fully, we risk losing sight of a broader, crucial fact: neither the American Revolution that Washington helped lead nor the new nation that he helped govern would have succeeded or endured without foreign alliances, including a foundational one with a Muslim country.

One of our most crucial Revolution-era alliances was with France, in a partnership advanced by two influential individuals: Silas Deane and Gilbert du Motier (better known by his title, the Marquis de Lafayette).

Deane, a Connecticut merchant and Continental Congress delegate, was appointed in March 1776 as a secret envoy to France, seeking to secure financial support (if not political alliance) from that nation’s government. He and his colleagues would spend nearly two years pursuing that goal, eventually securing the February 1778 Treaty of Amity and Commerce and Treaty of Alliance that officially linked France to the Revolutionary cause.

Just as significant was Deane’s influence on the Marquis de Lafayette, a 20-year-old Frenchman. Lafayette had already expressed enthusiasm for the American Revolution by the time Deane arrived in France, but through their relationship he took his first formal actions in support of the cause: Deane enlisted Lafayette as a major general in the Continental Army in December 1776. The Continental Congress did not have sufficient funds to bring Lafayette to the U.S., so Lafayette bought his own ship (the Victoire) and sailed for America. He arrived in South Carolina in June 1777 and spent most of the next four years in the United States, both fighting in Revolutionary battles and helping secure further French support and reinforcements for the cause. Those joint efforts culminated at the August-September 1781 Battle of Yorktown, where Lafayette coordinated a fleet of French warships to rout the British navy, blockade and lay siege to General Cornwallis’ troops, and eventually join Washington’s forces in eliciting Cornwallis’ surrender (which effectively ended the war).

Without the individual efforts of Deane and Lafayette, and more importantly without the political and military alliances that they secured and helped bring to America, the course of the American Revolution certainly would have diverged. At the very least, the war would have gone on far longer, and for a Revolution where both financial backing and citizen support were always fragile and imperiled, that kind of extension might well have produced a different outcome.

That success wasn’t just about victory on the battlefield. If the United States were to endure beyond the Revolution, it would also need economic and social (as well as military and political) alliances with foreign nations. The first such economic partnership was offered very early in the Revolution by an unlikely ally: the North African Muslim nation of Morocco. On December 20, 1777, Morocco’s progressive leader, Sultan Sidi Muhammad Ibn Abdallah, wrote letters to European merchants and ambassadors throughout North Africa stating that American ships would be free to enter Moroccan ports under the same conditions as those from any other independent nation. While not yet a formal treaty, this statement represented the first recognition of an independent United States by any nation in the world, and along with that symbolic value offered a key international trading partner during those economically challenging Revolutionary years.

Both the Revolution and the threats of Mediterranean piracy kept the two nations from formalizing a treaty for a few years, but in June 1786 the U.S. emissary Thomas Barclay secured a Treaty of Peace and Friendship between the United States and Morocco. In early 1787 Thomas Jefferson and John Adams signed the treaty in their roles as foreign ministers to France and England respectively, and in July 1787 the Confederation Congress ratified the treaty. That treaty, the first of a series that came to be known collectively as the “Barbary Treaties,” did more than just cement the Revolutionary-era friendship between the two nations. It made clear that the new United States was an economic and political actor on the world stage, one whose relationships and alliances would extend far beyond Europe. It also helped facilitate Moroccan immigration to the U.S., which created the influential “Moorish” American community in 1780s Charleston, South Carolina.

On December 1, 1789, just a few months into his first term as president, George Washington wrote a letter to Sultan Abdallah, formally extending the “Thanks of the United States, for [the Sultan’s] important Mark of your Friendship for them.” He added, “It gives me Pleasure to have this Opportunity of assuring your Majesty that, while I remain at the Head of this Nation, I shall not cease to promote every Measure that may conduce to the Friendship and Harmony, which so happily subsist between your Empire” and the U.S.

Less than a decade after corresponding with the Sultan, George Washington was writing his farewell letter, advising a more “detached and distant” relationship with foreign nations. Ironically, only a few years later, we became embroiled in a naval conflict with France known as the “Quasi-War,” which featured the very bickering over debt, trade, and political maneuvering that Washington was likely hoping to avoid. But by remembering America’s early relationships with France and Morocco, we can engage with the crucial role played by foreign alliances in both the American Revolution and the nation’s enduring existence.

Featured image: Detail of painting featuring Washington and Lafayette at the Battle of Yorktown (Auguste Couder, Palace of Versailles)

Spying for George Washington: The Culper Ring

“I only regret that I have but one life to lose for my country.”

This was the last declaration of Nathan Hale, the American Revolution’s most famous spy. Officially recognized as an American hero, Hale has been embraced as a symbol of rebellion and is the namesake for schools, dormitories, inns, and book series. While Hale’s name is widely known, the most successful spies of the Revolution, the Culper Spy Ring, did not achieve such fame.

But the point of spying is secrecy; the most successful spies are the ones you’ve never heard of.

When Nathan Hale agreed to spy for the Continental Army, he was agreeing to put himself at incredible risk. Soldiers captured behind enemy lines were sent to prison camps, but spies were hanged on the spot. Hale was to change out of his uniform, go behind enemy lines, ask around about what the British were up to, and then simply walk back to camp with the information. This style of spying was common practice at the time, but it is what led to Hale’s capture and execution on his very first mission. The loss of Hale hit the patriots hard, particularly his old college friend Benjamin Tallmadge.

Tallmadge was a preacher’s son from Setauket, New York, serving as a major under General George Washington. Having risen through the ranks of the Continental Army, Tallmadge understood the importance of good intelligence and the risks it took to get it. With the war going poorly for the American underdogs, Washington tasked Major Tallmadge to find reliable informants. Washington’s focus was New York City, the first major American defeat of the war and the new British headquarters. Swarming with red-coats, the city held the secrets of the war and was near impossible to enter.

But Tallmadge was determined. In 1778, he created the Culper Spy Ring, which consisted of the most trustworthy people he knew: his childhood friends. Abraham Woodhull, a Setauket farmer, used selling his crop to the British army as an excuse to access New York City and a reason to talk to soldiers. Using fellow Setauket natives whale-boatman Caleb Brewster as a courier and Anna Strong as a signal, Woodhull gathered information on British troop numbers and movements. Brewster brought Woodhull’s information to Tallmadge, who informed Washington.

LaToya Morgan, a writer and producer of Turn: Washington’s Spies, an AMC series based on the actions of the Culper Ring, notes, “I find it remarkable that this actually happened,” that “a group of friends” worked with George Washington in the middle of the revolution. The show presents a dramatic retelling of the spy ring’s actions, using historical fact to “play within the lines of what was there.” The mystery surrounding exactly what happened leaves a lot of room for the show’s writers to fill in.

The spy ring gained more members as the war went on. Robert Townsend, a New York City café owner, signed on as another informant, and Setauket native Austin Roe helped to act as a courier between New York and Setauket. Occasionally the New York tailor-turned-spy Hercules Mulligan would aid the ring, but he is not considered an official member. The ring was also aided by a mysterious “Agent 355.” In the code used by the ring, this title simply meant “lady,” and nothing further was stated about her identity in official reports. In Turn, 355 is depicted as a former slave of Anna Strong working for British head of intelligence John André.

In addition to using exclusively non-military people, the ring employed several other new means of cryptography. All messages were sent in numbered code and signed using code names. Tallmadge went by John Bolton, Woodhull was Samuel Culper, and Townsend was Culper Jr., giving the ring its name. And seemingly straight out of Hollywood, the ring used actual invisible ink and coded newspaper articles to send messages. The secrets of the ring remained so secure that not even George Washington himself knew the identities of all of his agents. The ring’s success at protecting the identity of its members sparked a more modern method of spying.

The Culper Ring is believed to be the most successful chain of information on either side of the Revolutionary War. It helped uncover the betrayal of Benedict Arnold as well as capture John André. Without information from the Culper Ring, Lafayette’s French troops would have been attacked by the British as soon as they arrived in the colonies, likely ending essential French involvement in the war.

The most remarkable thing about the ring, however, was that none of its members were ever discovered. All members of the ring survived the war and went back to their normal lives. It wasn’t until years later that letters and reports were discovered and the world learned just what had happened.

LaToya Morgan finds it surprising how little about the revolution is taught today in schools. “I can’t believe I didn’t know Washington was a spymaster.” Primarily known as a general and president, Washington’s secretive past is mostly ignored. Ms. Morgan believes it is due to the general’s secrecy that the Culper Ring is not more well known.

The secrets of the Culper Ring were so well guarded that it took 150 years to discover the identity of Culper Jr., and the identity of Agent 355 is still unknown.

“Ordinary people working with George Washington,” Morgan says. “It’s a great David and Goliath story.” A group of non-military people in a small town did what they could against the might of the British army, embodying the spirit upon which this country was founded.

Featured image: American spy master and leader of the Culper Ring, Benjamin Tallmadge. Shutterstock

“Prevarication Jones” by Leonard Wibberley

Leonard Patrick O’Connor Wibberley (1915-1983) was the Irish-born author of more than 100 books under his name and three pen names — Patrick O’Connor, Leonard Holton, and Christopher Webb — as well as numerous short stories, several published in the Post. His most famous work, The Mouse That Roared, originally appeared in 1954 as a six-part serial in The Saturday Evening Post under the title “The Day New York Was Invaded.”

Originally published on June 2, 1962

Everybody who knew him — and that included all the settlers along the Monongahela and a fair number farther west on the Ohio — agreed that he was the biggest tarnation liar west of the Alleghenies. They made this remark judiciously, aware that there was a lot of territory west of the Alleghenies and that in the year 1784 this territory included some of the most beautiful liars ever produced by a young, vigorous, and imaginative nation. Even his name attested to his reputation, for he was called Prevarication Jones.

“The Prevarication part is true,” the boy’s father said. “But as to Jones — why, I reckon that must be a lie like everything else, and his true name is likely Robinson or Williams or something like that.” And then he gave a deep chuckle, a kind of hen’s clucking as it were, in amusement at a man so talented in lying that people couldn’t even bring themselves to believe that his name was what he said it was.

Prevarication Jones made three and sometimes four trips a year to the settlements along the Monongahela. His headquarters — or what he said was his headquarters — was Philadelphia. He was a packman, and on each trip, he brought with him, besides his own mount, two packhorses whose saddles were laden with the kind of goods the settlers liked to buy. For the men he had English axheads and tenpenny nails and hammerheads and belt buckles — mostly of horn, but one or two special ones of hard iron. Also lead and bullet molds and springs with which to repair the cocking mechanism of their rifles. Sometimes, on special order, he would bring a rifle with him. But mostly he carried an assortment of parts from an assortment of rifles that his customers would paw through, looking maybe for a pan or a hammer or a spring or some such thing that would fit their own weapons.

For the women, Prevarication Jones brought mostly soap. To be sure, the women of the settlement — five families, including the boy’s — could make soap of their own with fat and lye. It was good soap, but rough, and burned their hands if they got too much lye in it. But Prevarication Jones brought them special soap — Windsor soap, it was called. It was in nice little oval cakes and looked pretty, pink and yellow and white. And it was scented soap, smelling of roses or violets or some other flower.

All the women bought one or two cakes of the Windsor soap — “Made to the King’s own formula,” Prevarication Jones would say, as solemn as a parson at his psalms. They kept the cakes of Windsor soap on a high shelf in their kitchens and used it sparingly. The boy sometimes got a stool and reached up for his mother’s cake of soap and sniffed at the fragrance in pleasure. He particularly liked to do this in the winter — to get the smell of roses when all around was deep in snow. That was a kind of miracle. Prevarication Jones was the man who made it possible, and the boy adored him.

Prevarication Jones traveled alone all the way from Philadelphia. The Indians weren’t much trouble anymore — not like they had been 20 years ago. And in any case he was a veteran not only of the frontier but also of the Revolutionary War and feared, as he put it, “neither man nor beast, savage or tame, but only God Himself.” And then he would add with a shy smile, “And Him and me been friends for many a year.”

The settlement in which the boy lived was on the right bank of the Monongahela, on a bluff overlooking the river. It was called Platts Landing, and the boy’s father, Ephraim Platt, had built the first loghouse there. That was 15 years or so before, and though Ephraim Platt was not conscious of this, he was a part of the westward movement of the American people that followed the Revolutionary War and would spill over the Ohio and on into the territories even beyond the Mississippi until the time would come when there would be Americans living all across the continent from the Atlantic to the Pacific.

Others had come after Ephraim — the Blacks, from New Jersey, two years after; the Sawyers from Northeastern Pennsylvania a few months after the Blacks, and then the Pols and the Wainwrights. They all looked to Ephraim Platt as the oldest settler, and it was at his loghouse — there was a wall of stakes around it in case of Indian attack — that they met for social occasions.

In the settlement there were eight children of schooling age and five babies, and Mrs. Platt was of the opinion that the time had come to start a school. She was a very quiet woman and small, with hair so fair that, though there were several gray strands in it, they didn’t show. Her hands were small and her feet were small, and she always looked neat, even when she had on the old black work dress that she wore while about her chores.

“We’ve got to have a schoolhouse, Mr. Platt,” she said one evening to her husband as they sat down to their supper. “There’s eight children in this settlement should be at school this very day.”

“Then let their mothers teach them,” said her husband. “Boy, pass the salt dish. Deer meat can stand a lot of salt, Mrs. Platt. Beef comes salty, being cured. But deer meat is fresh and must be salted if a man is to get any strength from it.”

He reached out a big arm, and the boy passed the enameled bowl with the salt to his father. There was a Bible in their house and a picture in it of John the Baptist. Under the picture were the words A VOICE CRYING IN THE WILDERNESS. The picture showed a big man with long hair and a huge black beard that came to the middle of his chest. It looked very much like the boy’s father, and he sometimes thought of his father as John the Baptist; a voice crying in the wilderness. Crying about what? Crying about America. Some message about America and how the people must come and settle the land and make the nation bigger.

“That first little loghouse that we built, Mr. Platt,” said the boy’s mother, “would make a tolerable schoolhouse for now. Later we will want something bigger.”

“That whole tale of yours about Bunker Hill is a lie, and you know it. You weren’t there and neither was George Washington.”

“So it would,” said Mr. Platt. “So it would. It would indeed. There is no doubt about it.” When he sensed that he was being driven into a corner by his wife, Mr. Platt, for all his big size, capitulated without any fight at all. He agreed, as it were, with an overabundance of concord, asserting in several different ways that what she said was absolutely right. Sometimes he found that by these tactics his wife would become uncertain and retreat from her position, and the matter would be dropped. But this was not such an occasion.

“Good,” said Mrs. Platt. “Then that is settled.”

“So it is,” said Mr. Platt. “So it is. Except for a few details. As, item: what about slates to write on? And what about books to learn out of — spellers and such like? And what about benches to sit on? And what about someone to teach school?”

“We can get spellers and slates from Prevarication Jones,” said Mrs. Platt.

“And who’s to hold school?” asked Mr. Platt. “Not the men. They’re busy in the fields. Nor the women, for they’re busy in the fields too. Or with washing or mending clothes or making soap or cooking meals or caring for the babies. So who’s to teach school? Answer me that, Mrs. Platt.”

But it was the boy who answered. He didn’t mean to answer. It just popped right out of him. And what he said was, “Prevarication Jones.”

The boy’s father had a gobbet of deer meat on his hunting knife halfway to his mouth when the boy said “Prevarication Jones.” The knife remained in mid-passage, and Mr. Platt’s mouth, the lips showing pink through his black beard, remained open, frozen for a second in surprise.

“Prevarication Jones!” he roared, when he had recovered. “There’s a fine schoolmaster for you. The biggest tarnation liar west of the Alleghenies. Why, he’d stuff their young heads with nonsense until they couldn’t tell black from white.”

Mrs. Platt exchanged a quick look with her son. She saw that his eyes were brighter than they should be and his face pale with anxiety.

The boy lowered his head quickly and said, “I don’t think he’s a liar. Not on important things.” He didn’t say this very loud. He was talking to himself really, assuring himself that this was so. But his father heard him.

“Not really a liar, eh,” he said. “Not on the important things, huh? Well, I can tell you everything he says is a lie, and what is particularly a lie is that story of his about the Battle of Bunker Hill. I know that’s a lie, and if he had any regard for his reputation, he would leave that one out when he’s spinning his tales.”

“You enjoy the tale yourself, Mr. Platt,” said his wife.

“Ah, so I do,” replied her husband. “And that other one about being with John Paul Jones on the Bonhomme Richard. Enjoy them very much. But they’re both lies, like everything he says.

“Now I’ll tell you what. If Prevarication Jones will just admit to that tale of Bunker Hill being a lie, there might be some hope for him as a schoolmaster. But otherwise, no.”

“Admit it or prove that it is true,” said Mrs. Platt, looking at the boy. For answer, Mr. Platt snorted and left the table.

Prevarication Jones visited the settlement two weeks later. That was at the end of June. He had his usual assortment of goods, not forgetting the scented soap for the women. And for Mrs. Platt he had brought a little silk bag full of lavender seeds.

“I mentioned your name to my friend Mr. Franklin — Benjamin, that is,” he said. “And he asked me particularly to bring this to you. The great ladies of France wear them sewn in their dresses, and he had it from the Countess of Vercennes. He would take it as a favor if you would accept it from him, though a stranger.”

Mrs. Platt was all blushes as she took the little silken sack of lavender and sniffed it and then handed it to all the other women, who exclaimed over it with gasps of pleasure. The men stood around grinning. They liked Prevarication Jones. There was no harm in him at all, and the little gifts he brought for the women gave them the kind of pleasure that they, in the rough frontier life, could not provide and indeed did not even think of. That lavender bag, for instance. It was certain that Benjamin Franklin had never seen it. But it was a pretty woman’s thing, and long after the last fragrance had gone, Mrs. Platt would treasure it and might even come to believe that once it had been worn by one of the great ladies of France. So she would have a tiny link, even if it were imaginary, with Paris and the great, exciting world beyond the mountains.

When he had made the initial sales from his pack and given all the women some little trinket — always with a sort of footnote that it had once belonged to some great man or woman — Prevarication Jones was brought into the Platt house and given a meal of breast of venison with corn stuffing and potatoes and a special gravy that he pronounced superior to the best to be had anywhere.

And then, for this was always the custom during his visits, the whole settlement gathered in the Platt loghouse, and listened while Prevarication Jones told story after story. Some of the tales his audience had heard before, but nonetheless they delighted in them. There was the tale of the Maumee Indian chief he had met and whose life he had saved.

“He gave me,” said Prevarication Jones, “this stone here. It is a bluish stone as you can see, and it has this curious property, that laid between any wound and the heart, it will instantly combat any malignancy and speed the healing of the wound in a miraculous manner.”

The stone was passed from hand to hand, the children holding it the longest, their eyes big with wonder. One little girl put it on her doll, from which the foot was broken off. Seeing this, Prevarication Jones exchanged a barely perceptible nod with her mother, and the boy knew what that meant. Prevarication Jones would provide a new foot for the doll during the night when the girl was asleep.

Then he told the story of the eagle that had carried away a sleeping child in the Hampshire Grants and how by using a bullroarer — that is, a long string with a weight on the end, whirled above the head to produce a deep hum — he had charmed the eagle to the ground and returned the infant unhurt to its mother

It was Ephraim Platt who, not without a measure of vindictiveness, prompted him to tell the story of Bunker Hill.

“June 17, 1775,” said Prevarication Jones, for this was the way he always commenced his account. “And as nice a day as a man could expect in that part of the world. I particularly recall the grasshoppers singing in the long grass before our works. The grass came up the flanks of the hill toward our works. It was pale gold and should have been cut for hay, but had been left until the summer was a little further advanced. It was to be cut that day, though — not by scythes, but by bullets. The British lined the foot of the hill at the shore, and some of their war vessels had been bombarding us all morning. Now you’ll say it’s strange that over cannon shot I could hear the grasshoppers singing. And yet I could, and thought it strange myself. Most of the shot was spent when it reached us and rolled along the ground like bowling balls — 18-pounders they were.

“We’d been all night putting up the defenses. Mostly we dug a ditch and threw the earth in front in barrels and sacks and suchlike containers, and were thirsty about noon. Two boys went back over the peninsula, but all they could bring for us to drink was rum, and heady stuff it was too.

“About noon, I would say, the British were ready. There were three lines of them at the foot of the hill — three red lines as straight as pokers. I remember an English officer’s voice saying something quite sharp, though I couldn’t catch the words. Then there was another voice, and the words came to us clear, for the cannon fire had died down. They were, ‘The infantry will advance on the enemy’s works.’ It gave me quite a turn, hearing that quiet voice coming up the hill and realizing that we were the enemy. Three meadowlarks rose up in the air right then out of the long, pale-gold grass, and I thought it might be a sign of some kind. I turned around because it frightened me to see those redcoats come on in such fine formation and saw Gen. Washington standing right behind me.

“‘Don’t shoot until you see the whites of their eyes,’ he said, and I can tell you that those words steadied every mother’s son of us. …”

So the tale went on, very vividly told, of the repulse of the first assault and then the second assault and then the lack of powder and men giving a ragged volley and doing what they could with spades and mattocks against the English bayonets. Not a word was uttered by the audience during the telling, and at the end there was a stirring, like a sigh of content and pride that the challenge had been met. The men had stood and America had been born that day.

Even Ephraim Platt was moved and, watching his son’s solemn face, his small jaw set tight and his lips pulled into a thin line, he was glad that he had not interrupted, as he had planned, and pointed out that he knew for a fact that George Washington had never been present at Bunker Hill and Prevarication Jones neither and so the whole thing was suspect.

But, moved as he was, he still was determined that the man wouldn’t do as a schoolmaster. His wife might be set on it and the boy might want it, but a schoolmaster had to know the truth from a lie. And Prevarication Jones didn’t.

Ephraim Platt, though a man of sentiment, was also a man of purpose. And when the audience had gone and the boy had gone to bed, he confronted Jones before the dying fire.

“Mr. Jones,” he said, “that whole tale of yours about Bunker Hill is a thundering lie, and you know it. You weren’t there and neither was George Washington. He didn’t take command of the Continental Army until after the battle had been fought.

“Now,” he continued, “there’s some thought of starting a school here, and Mrs. Platt has you in mind for a schoolmaster. You are an educated man, I have no doubt. But you’ll understand that we can’t have a schoolmaster who is a tarnation liar. If you’ll admit to me, man to man — just me, mind you — that that story of Bunker Hill is nothing but lies, since you weren’t there nor George Washington neither, then you can settle here and teach school, and the community will support you. Otherwise it’s a packman’s life for you to the end of your days. And you are not getting any younger.”

“Mr. Platt,” said Prevarication Jones, “I regret that you take that view of my tale. And now, sir, I am weary and would like to sleep.”

The boy watched him for a while as Prevarication Jones lay on the two benches which served him as a bed before the fire. He did look old. What happened to packmen when they were old? the boy wondered. Who took care of them? It became all the more important that Prevarication Jones become the schoolmaster in the settlement. But he would never admit that George Washington had not spoken to him at the Battle of Bunker Hill. Maybe it wasn’t true, but Prevarication Jones, the boy sensed, would never admit it. And then maybe it was true. There was only one man who could say so, one way or another — a man who had a reputation for never telling a lie.

The boy went over to his mother’s bed. She woke, as she always did, as soon as he stood beside her. He bent over and whispered something in her ear so as not to disturb his father, and she got quietly out of bed after only a slight demur and, taking a sheet of paper and a pen, started to write at the kitchen table.

Prevarication Jones left early the following morning, announcing that he would likely be back in September, and all summer long the boy kept thinking about him. The school was opened in the settlement, and the women took turns at teaching, but it was not really satisfactory because, although they could teach ciphering and arithmetic and reading, they knew little of history or geography or other subjects. And sometimes they were too busy to teach, and there was no school. Even Ephraim Platt agreed that it was not a satisfactory arrangement.

In September he will be back, the boy told himself all summer long. And then my father will see that he should stay here and teach school — even if he is the biggest tarnation liar west of the Alleghenies.

Prevarication Jones did come back in September, but a little later than usual, and it was plain that he was not well. The journey had tired him, he said, and he talked about mountain sickness and said he knew of a particular root shown him by an African when he was on the Barbary Coast that would cure him. It grew hereabouts as well as in Africa. He must first rest and then find the root and all would be well.

“It’s your fault, Mr. Platt,” said his wife, when she got him by himself. “You’ve taken the heart out of him. He’s not telling his tales the way he did. You should be ashamed of yourself.”

“What? For telling him he’s a liar?” said her husband.

“No gentleman would do such a thing,” replied his wife.

“A liar’s a liar,” said Mr. Platt.

“And a gentleman is a gentleman and wouldn’t say so,” said his wife in unaccustomed rebellion.

Prevarication Jones stayed a week, but grew weaker rather than stronger. To be sure, the women brought him broths and soothing drinks and fussed over him and made the children play away from the Platt house so he could get some rest. But, as Mrs. Platt had said, his illness was of the spirit, and without the spirit the body could do little.

Finally one day Mr. Platt took his son aside. “Boy,” he said, “do you write well?”

“Yes,” said the boy.

“I mean ciphering, not printing. I can print myself.”

“I cipher well if I have the good quill,” said the boy. “The one Mr. Jones brought from Philadelphia. The one that was used by Mr. Jefferson to write the Declaration of Independence.”

The father flushed and was about to say something about tarnation lies, but checked himself. “All right,” he said. “Get it and some paper and some sealing wax and bring it over to the schoolhouse. I have a letter for you to put down as neat as you can. Say nothing about it to anybody.”

The boy did as he was told, and the letter was written.

That night the neighbors assembled again in the Platt house, as was their custom. Prevarication Jones was there in the chair that was reserved for him, but nobody expected him to tell any stories because he was feeling so poorly. To thank them, he tried, but every time his eyes met those of Mr. Platt, he failed and the spirit went out of his tale. In telling the story of the Indian chief and the wonderful blue stone, he did not even bother to produce the stone, such was his lack of animation.

“I have an apology to make in your presence to Prevarication Jones,” said Mr. Platt, blushing but resolute, when this particular tale was done.

“I had accused him privately when he was last here of lying about the Battle of Bunker Hill. I told him that George Washington was not there at that battle, and so his whole story was a lie. But I have got a letter brought down the river that shows he was right and I was wrong. Boy, give me that letter.”

The boy reached for the letter his father had dictated to him and about which he had been told to say nothing, but to be ready to produce it. But, even while he was fumbling in his pocket, Mrs. Platt was on her feet. Blushing slightly, she herself produced a letter — a letter with a big wax seal on the cover and addressed in a florid and forceful handwriting.

“I think this is the letter you want, Mr. Platt,” she said in her small but determined voice. “It came by the keelboat yesterday.”

Much disconcerted, Mr. Platt took it from her, turned it over a couple of times, opened it, glanced at the signature at the bottom, and started reading. It went:

Madam: I trust you will forgive the delay in replying to your letter about one Prevarication Jones and his part and mine in the Battle of Bunker Hill. I have read with interest your story of his account and have been deeply moved by it.

The Continental Army was made up of many men such as Prevarication Jones. It was they, rather than I, who saw the Revolution through to success. It is their tale, quite as much as mine, that should be given credence by their fellows in the recounting of the many battles they fought against appalling odds. Let me say that I am indebted to Mr. Jones for making me the hero of his tale, and let me add also, Madam, that I could not, with honor, quarrel with a word of it.

Your Obedient Servant,

George Washington.

There was a deep silence when Mr. Platt had finished reading this letter. All eyes were on Prevarication Jones, who was working his mouth and who raised his sleeve for a moment and brushed it fiercely against his cheek.

“I trust, Mr. Jones,” said the boy’s father, “that you will forgive me for my doubts and stay here with us in Platts Landing and school the youngsters. We’d be proud to have you, if you are so minded.”

Prevarication Jones looked straight at Mr. Platt and then reached a trembling hand out for the letter. He read it through in silence himself and put it carefully inside his deerskin tunic.

“June 17, 1775,” he said suddenly and fiercely, and launched again into the tale of the Battle of Bunker Hill, told with all his old vigor.

He’ll be our schoolmaster then, said the boy to himself.

And suddenly he was filled with a great surge of love not only for Prevarication Jones but also for his father and for another fine gentleman and soldier who lived hundreds of miles away, whose honor was beyond question, who had stood by his friend, and whose name was George Washington.

For more about Leonard Wibberley and his work, visit leonardwibberley.wixsite.com/author.

This story is featured in the May/June 2019 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Featured image: Shutterstock

Considering History: Thomas Paine’s The Crisis and Finding Hope in the Depths of Winter

This series by American studies professor Ben Railton explores the connections between America’s past and present.

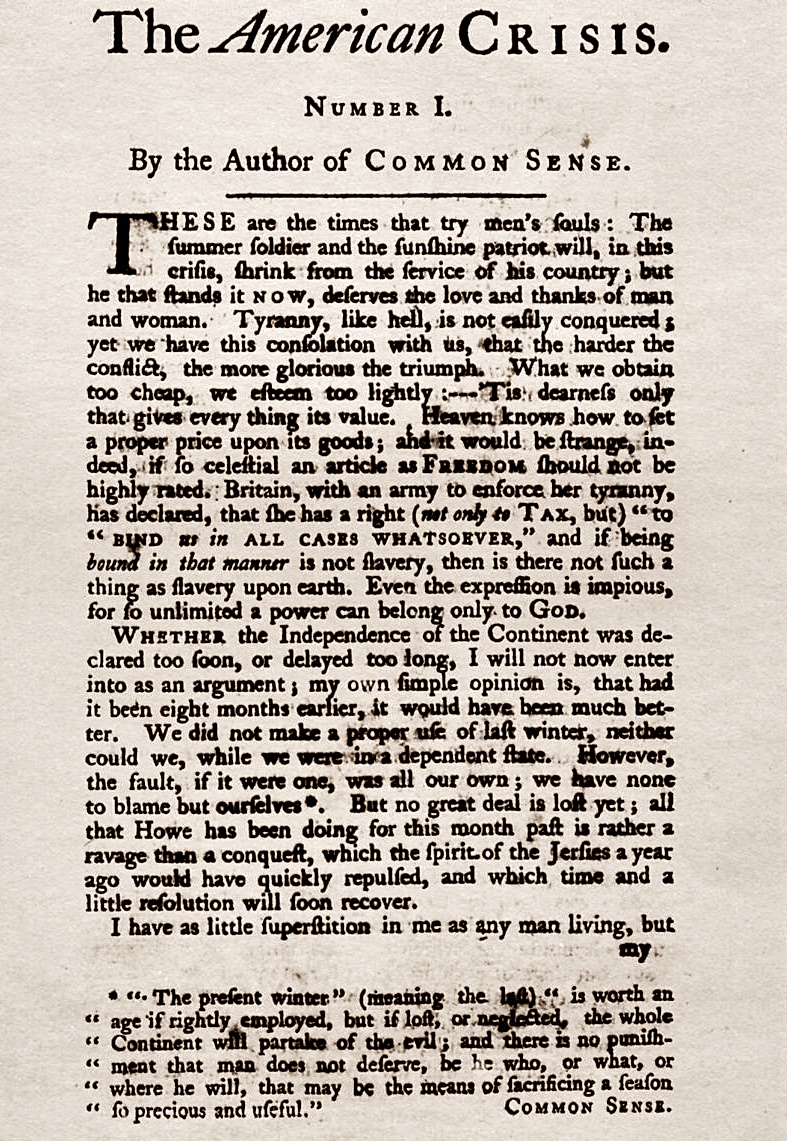

On December 19th, 1776, the firebrand journalist and activist Thomas Paine (1737-1809) published the first volume of his political pamphlet The Crisis (also known as The American Crisis). The Crisis would feature five more volumes over the next twelve months, documenting much of the first full year of the incipient American Revolution against England. Paine would go on to release thirteen additional volumes between 1778 and the Revolution’s 1783 conclusion, continuing to trace the conflict’s evolution and to add his passionate support to the colonist cause at each stage.

That December 19th number begins with some of the most eloquent and inspiring lines in American history:

These are the times that try men’s souls. The summer soldier and the sunshine patriot will, in this crisis, shrink from the service of his country; but he that stands it NOW, deserves the love and thanks of man and woman. Tyranny, like hell, is not easily conquered; yet we have this consolation with us, that the harder the conflict, the more glorious the triumph. What we obtain too cheap, we esteem too lightly: ‘Tis dearness only that gives everything its value.

Those impassioned words offer inspiration for resistance and persistence in the face of the darkest times and challenges. But if we add biographical and historical contexts for this seminal American author, we gain an even deeper sense of the inspiration he can offer us in these modern times.

Paine’s biography highlights the depth and breadth of his activist roots. He had immigrated to America from England only two years prior, in November 1774, arriving in Philadelphia with little more than a letter of recommendation from Ben Franklin. Franklin’s impression of Paine as “an ingenious, worthy young man” was based in part on the perspective of a mutual friend, the London mathematician and politician George Lewis Scott. But it was also based on Paine’s own burgeoning public and activist career, highlighted by his 1772 article “The Case of the Officers of Excise.” In that work Paine launched a lifelong career fighting for the rights of minorities and the common man against entrenched, powerful interests.

Paine continued those efforts, and extended them into the realm of journalism, not long after his arrival in America. When Philadelphia printer Robert Aitken founded Pennsylvania Magazine in February 1775, with the intent of making it the first “American magazine,” Paine contributed two pieces to the inaugural issue. A month later Aitken would name Paine the editor, and in that role Paine would both write and publish a great deal of his political and social activism, including support of controversial causes like the abolition of slavery: in March 1775 the magazine published the anonymous abolitionist essay “African Slavery in America” (a piece that Benjamin Rush would later attribute to Paine himself), and in April 1776 it published ex-slave Phillis Wheatley’s stirring Revolutionary poem “To His Excellency General Washington.”

Between those journalistic efforts and his January 10th, 1776, Revolutionary pamphlet Common Sense, Paine had by 1776 established himself as one of America’s most impassioned and vital political and social voices. But by December of that year, much had changed in the American Revolutionary situation, and more exactly the cause was at a strikingly low point. Washington and the Continental Army had been involved for months in the New York and New Jersey campaign, and that campaign was going poorly: by early December Washington had lost a number of engagements with the forces of British General William Howe, and the American troops had withdrawn across the Delaware River, leaving New York and New Jersey in mostly British hands. Congress had even withdrawn from the city of Philadelphia, and it seemed quite possible that both the Continental Army and the Revolution itself would not survive this first post-Declaration of Independence winter.

This was certainly not a moment when summer soldiers and sunshine patriots could hope to find much warmth, a particularly fraught period that makes clear why Paine capitalizes “NOW” in his pamphlet’s opening lines (his only such capitalization there). It’s not just that Paine’s pamphlet was directly inspired by surrounding events, though—it also quite possibly influenced those events. A few days after the pamphlet’s initial publication, Washington likely read a reprint aloud to his men, with whom he was camped in Pennsylvania. The historical record is ambiguous on whether the general actually read The Crisis aloud, as this article traces, but Washington and the army at least knew of and were inspired by the pamphlet soon after its publication. On the night of December 25th, Washington led many of those troops in the famous crossing of the Delaware, a surprise attack on the British forces at Trenton that significantly shifted the course of not only this campaign but the whole early Revolutionary conflict.

It’s easy to see such historical moments as inevitable in hindsight, but of course it was anything but, just as the outcome of the Revolution was far from certain in December 1776 (and would be precarious for many years to come). Those uncertainties help us understand the existence of Paine’s pamphlet—and also help us see the role that Paine’s inspiring words played in helping carry those Revolutionary efforts forward. As we move deeper into our own winter of discontent, Paine’s words, life, and perspective can offer inspiration to us today.