This series by American studies professor Ben Railton explores the connections between America’s past and present.

Those seeking to advance arguments for American isolationism have long found clear support in a foundational national text: George Washington’s “Farewell Address,” originally published in the American Daily Advertiser in September of his final year as president (1796). Washington’s piece, co-written by James Madison and Alexander Hamilton, moves through a series of topics, but features a substantial concluding section that warns against “foreign entanglements” and supports an isolated stance in world affairs. “Our detached and distant situation invites and enables us to pursue a different course,” Washington argues. “Why forego the advantages of so peculiar a situation? Why quit our own to stand upon foreign ground? … It is our true policy to steer clear of permanent alliances with any portion of the foreign world.”

While Washington was responding to the specific contexts of late 18th century European conflicts, his remarks also highlight the dangers of becoming too tied to any other nation’s political or global fortunes. But if we emphasize this one document too fully, we risk losing sight of a broader, crucial fact: neither the American Revolution that Washington helped lead nor the new nation that he helped govern would have succeeded or endured without foreign alliances, including a foundational one with a Muslim country.

One of our most crucial Revolution-era alliances was with France, in a partnership advanced by two influential individuals: Silas Deane and Gilbert du Motier (better known by his title, the Marquis de Lafayette).

Deane, a Connecticut merchant and Continental Congress delegate, was appointed in March 1776 as a secret envoy to France, seeking to secure financial support (if not political alliance) from that nation’s government. He and his colleagues would spend nearly two years pursuing that goal, eventually securing the February 1778 Treaty of Amity and Commerce and Treaty of Alliance that officially linked France to the Revolutionary cause.

Just as significant was Deane’s influence on the Marquis de Lafayette, a 20-year-old Frenchman. Lafayette had already expressed enthusiasm for the American Revolution by the time Deane arrived in France, but through their relationship he took his first formal actions in support of the cause: Deane enlisted Lafayette as a major general in the Continental Army in December 1776. The Continental Congress did not have sufficient funds to bring Lafayette to the U.S., so Lafayette bought his own ship (the Victoire) and sailed for America. He arrived in South Carolina in June 1777 and spent most of the next four years in the United States, both fighting in Revolutionary battles and helping secure further French support and reinforcements for the cause. Those joint efforts culminated at the August-September 1781 Battle of Yorktown, where Lafayette coordinated a fleet of French warships to rout the British navy, blockade and lay siege to General Cornwallis’ troops, and eventually join Washington’s forces in eliciting Cornwallis’ surrender (which effectively ended the war).

Without the individual efforts of Deane and Lafayette, and more importantly without the political and military alliances that they secured and helped bring to America, the course of the American Revolution certainly would have diverged. At the very least, the war would have gone on far longer, and for a Revolution where both financial backing and citizen support were always fragile and imperiled, that kind of extension might well have produced a different outcome.

That success wasn’t just about victory on the battlefield. If the United States were to endure beyond the Revolution, it would also need economic and social (as well as military and political) alliances with foreign nations. The first such economic partnership was offered very early in the Revolution by an unlikely ally: the North African Muslim nation of Morocco. On December 20, 1777, Morocco’s progressive leader, Sultan Sidi Muhammad Ibn Abdallah, wrote letters to European merchants and ambassadors throughout North Africa stating that American ships would be free to enter Moroccan ports under the same conditions as those from any other independent nation. While not yet a formal treaty, this statement represented the first recognition of an independent United States by any nation in the world, and along with that symbolic value offered a key international trading partner during those economically challenging Revolutionary years.

Both the Revolution and the threats of Mediterranean piracy kept the two nations from formalizing a treaty for a few years, but in June 1786 the U.S. emissary Thomas Barclay secured a Treaty of Peace and Friendship between the United States and Morocco. In early 1787 Thomas Jefferson and John Adams signed the treaty in their roles as foreign ministers to France and England respectively, and in July 1787 the Confederation Congress ratified the treaty. That treaty, the first of a series that came to be known collectively as the “Barbary Treaties,” did more than just cement the Revolutionary-era friendship between the two nations. It made clear that the new United States was an economic and political actor on the world stage, one whose relationships and alliances would extend far beyond Europe. It also helped facilitate Moroccan immigration to the U.S., which created the influential “Moorish” American community in 1780s Charleston, South Carolina.

On December 1, 1789, just a few months into his first term as president, George Washington wrote a letter to Sultan Abdallah, formally extending the “Thanks of the United States, for [the Sultan’s] important Mark of your Friendship for them.” He added, “It gives me Pleasure to have this Opportunity of assuring your Majesty that, while I remain at the Head of this Nation, I shall not cease to promote every Measure that may conduce to the Friendship and Harmony, which so happily subsist between your Empire” and the U.S.

Less than a decade after corresponding with the Sultan, George Washington was writing his farewell letter, advising a more “detached and distant” relationship with foreign nations. Ironically, only a few years later, we became embroiled in a naval conflict with France known as the “Quasi-War,” which featured the very bickering over debt, trade, and political maneuvering that Washington was likely hoping to avoid. But by remembering America’s early relationships with France and Morocco, we can engage with the crucial role played by foreign alliances in both the American Revolution and the nation’s enduring existence.

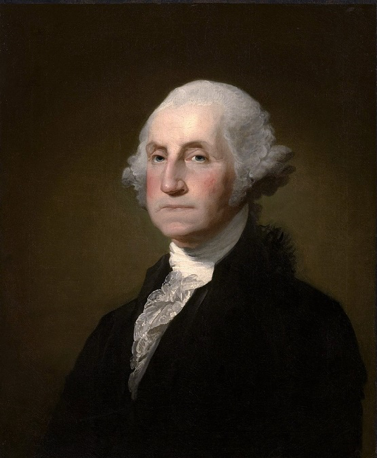

Featured image: Detail of painting featuring Washington and Lafayette at the Battle of Yorktown (Auguste Couder, Palace of Versailles)

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

I am already a Post member. I find the piece “Considering History” lucid and illuminating. The details of the Moroccan connections in question are new to me.

I am already a Post member. I find the piece “Considering History lucid and illuminating. The details of the Moroccan connections in question are new to me.

Thanks as ever for reading and your thoughts, Bob! More informed and collective conversation is one part of the more perfect union I’m working for, and I’m always glad to find it here.

Ben

After reading this fascinating feature and question you propose Professor Railton, I can only conclude the answer to be yes as well. Their help in the late 1700’s is what helped the our new country become the more autonomous nation we came to be to a fairly large extent (though never entirely) in the 19th and much of the 20th centuries.

As always, things are never entirely clear cut and some bad accompanies the good. This is part of the price for improvement in the big picture. This era may seem simpler to us now, but likely not for those running things then, and I would have to agree. It was likely (or seemed) equivalently complicated for that time to them.

Today we are mired in far too much choking bureaucracy, greed, everything rigged in favor of multi-billionaires and their best interests over everyone/everything else for starters. In addition we have unprecedented drama (24/7) with the President, followed by one unbelievable thing after the next, including the never-ending contradictions, party infighting and cliffhangers we see on the national news every night. The bottom line is crucial things in running this large country are not getting done or being discussed, due to the aforementioned.

I wish I knew what to do. I can say having the sense and sensibility of the U.S., French and Moroccan world leaders over 200 years ago regarding world affairs would go a long way today helping the U.S. on the international scene, making problems that do arise that much smoother and easier to resolve. That would be a huge accomplishment!