5 Times That Disease Unexpectedly Changed American History

Very few people foresaw the full impact of COVID-19 in America. And with the president’s recent announcement that he himself has been infected, there is much uncertainty about the repercussions his illness will have on his party, the government, the stock market, and the electorate.

But this is the nature of infectious diseases: the full impact of their arrival, departure, and consequences are rarely foreseen.

This has been seen repeatedly throughout history. During the Civil War, for example, America expected there’d be casualties from soldiers dying in the field of combat. What they didn’t expect was that most would die far from the fighting, as soldiers crowded in camps spread cholera, smallpox, and other infectious disease. More than half of the war dead were victims of disease.

Here are five times major illnesses had unexpected outcomes.

Malaria Fueled the American Slave Trade

Among the earliest European settlers to America were planters who arrived in South Carolina to grow rice. They soon discovered the marshy lowlands where they planted were infested malaria-bearing Anopheles mosquitoes. The disease, which reproduces in red blood cells, proved fatal for white workers in the fields, and planters had trouble maintaining their crops. But they discovered that recently enslaved Africans had a degree of immunity to malaria because of the genetic condition sickle-cell anemia. Rice became a successful crop, followed by cotton, both tended by slaves.

Planters didn’t know what gave the enslaved Africans their ability to endure malaria. They assumed it was because they were genetically hardier. This was far from true; half of all Black children born into American slavery died before reaching the age of five.

Disease Was a Sign of American Success

At the time of the Revolution, Americans enjoyed far better health than their contemporaries in Europe. The average height — a good indication of the state of health — was 68.1 inches, just one inch lower than the average height today (the average European measured 65.76 inches). Roughly 60 percent of children raised in the country survived to age 60. (page 123, “Deadly Truth”)

According to The Deadly Truth: A History of Disease in America by Gerald N. Grob, almost all Americans of the early 1800s resided in the country, leading exceptionally healthy lives. They lived far apart, with little exposure to strangers bearing illnesses; they had healthy diets and a clean environment.

But the population began shifting toward the cities, according to Grob. Between 1800 and 1850, for instance, the population of Philadelphia increased 500 percent, consisting mostly of Americans leaving the country for the city. They were attracted by the commercial possibilities and the opportunity to enrich themselves beyond anything they could realize on a farm.

They came despite the already high risk of contracting a fatal disease in the city. Between 1721 and 1792, Boston was hit by seven epidemics. An outbreak of yellow fever in 1793 killed 1 in 10 Philadelphians.

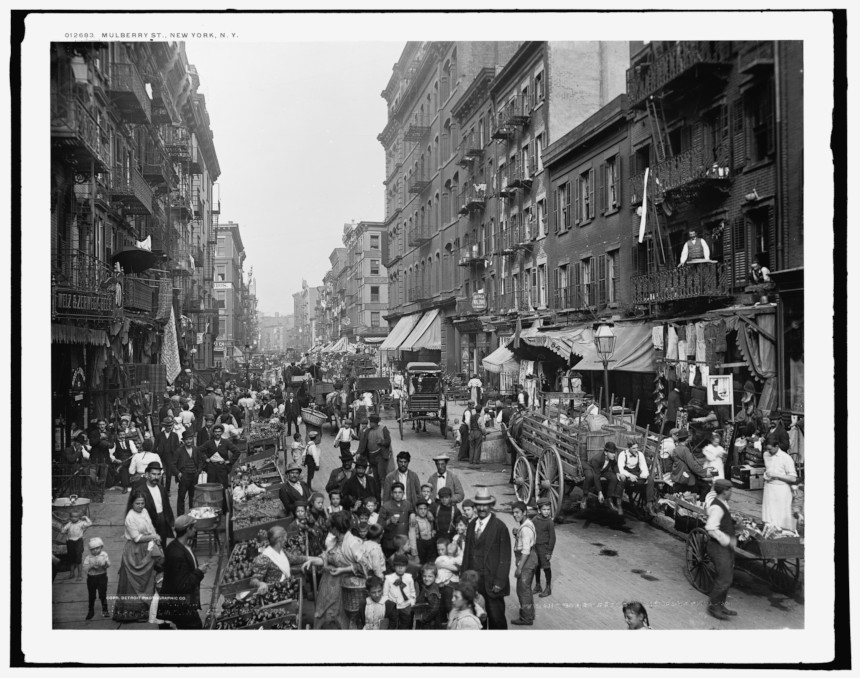

Urban crowding made disease transmission easier. Water supplies became contaminated. Immigrants, sailors, and visitors brought fresh injections of diseases. Cholera and yellow fever spread rapidly, and cities didn’t have the resources to care for the sick. In big cities like New York and Boston, only 16 percent of children reached their 60th birthday. By 1830, the average male height in America had fallen to under 67 inches.

A Mysterious Illness in Midwestern Livestock Began Emptying Towns

In the 1800s, settlers in the Ohio River Valley noticed livestock sometimes developed a trembling in their legs that soon led to collapse and death. Shortly afterward, their owners showed the same signs, as well as abdominal pains and vomiting. Farmers called it “milk sickness” and believed it was caused by an infectious agent.

The disease proved highly fatal in pioneer settlements, sometimes claiming up to half the residents. Areas of Kentucky and Illinois were especially hard hit. One of its victims was Abraham Lincoln’s mother.

The disease abated as the land became settled and animals began grazing in pasture land instead of the wilderness. It wasn’t until 1923 that Dr. Anna Pierce Hobbs Bixby learned from a Shawnee woman the cause of the sickness. Sheep and cattle were eating snake root, a member of the daisy family, which contains tremetol, a poison so strong it can kill animals and lethally poison its meat and milk. But in the days before it was discovered, the flow of settlers stayed away from areas where milk sickness was reported.

Another Disease Brought Prosperity to Colorado

America’s number-one killer in the 1800s was tuberculosis. Doctors didn’t understand its cause or course, but it seemed to be connected with damp, polluted air. So doctors advised TB patients to move to higher altitudes, where the air was dry and conditions sunny. The recommendation was partly useful. The decreased oxygen levels at high altitudes slowed the growth of the mycobacterium-causing organism. And the sunlight and fresh air was always good for patients.

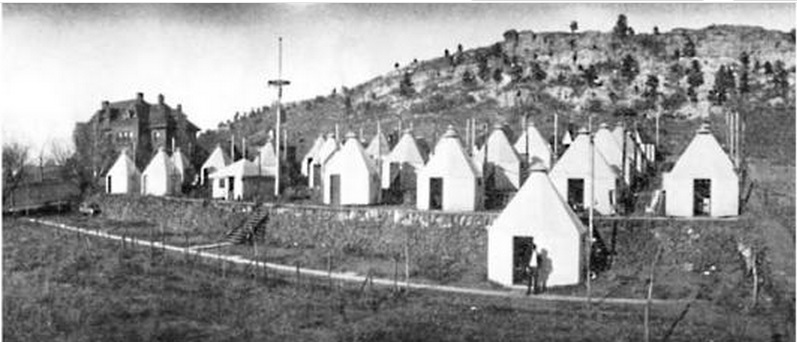

There were plenty of high altitudes and sunny weather in Colorado. Prior to the 1860s, it had been just another empty stretch of the western wilderness, sparsely peopled by miners and prospectors. But soon a growing number of sanitariums opened in Denver, Boulder, and Colorado Springs, and began to fill with tubercular patients. In time, they made up a third of the state’s population.

Cities grew up around the sanitariums, which attracted caregivers, support staff, and visitors to the patients. And TB patients often helped the town develop, bequeathing money to build streets and schools. In Denver alone, the population rose from 4,700 in 1870 to 106,000 in 1890.

Cleaning Up the Cities had Unintended and Fatal Consequences

Americans were shocked when a polio epidemic struck New England in 1916. For years, the incidence of the viral infections had declined almost to insignificance. Now, suddenly, 9,000 people had contracted the virus and 2,400 died — a fatality rate of 27 percent. The reason for the resurgence was completely unexpected.

Polio is caused by one of four viral strains. In the days before the Salk vaccine, most cases of polio ran their course in a day or two without serious complications. Only one case in 100 produced clinical symptoms, and even fewer caused paralysis. Most people experienced it as a low fever, headache, sore throat, and discomfort. But if the virus attacked the spine or the muscles controlling breathing, the consequences were quick and often fatal.

Up to the 1900s, most children in cities lived in crowded conditions and had been exposed to one of the strains at an early age. Or they gained immunity from maternal antibodies passed on to them as infants. Either way, most children growing up the congested cities were immune.

But as housing became less crowded and cleaner, there were fewer opportunities for exposure. A generation matured with little or no exposure and immunity. Polio swept through these communities quickly, striking down defenseless Americans. Franklin D. Roosevelt is a good illustration. He had grown up in wealth and comfort, and so had no immunity when the virus hit him in 1921 at the age of 39.

Featured image: Ward K, Armory Square Hospital, Washington, D.C., 1864 (Library of Congress)

Considering History: Uncle Tom’s Cabin and Imagining Slavery’s Family Separations

This column by American studies professor Ben Railton explores the connections between America’s past and present.

As historians and journalists such as Martha Jones, Anthea Butler, DeNeen Brown, and others have eloquently reminded us in recent weeks, one of the core practices of the American system of chattel slavery was the separation of children from their parents (among other purposeful and consistent family divisions). Even when parents and children were not sold away from each other (an all-too common way to achieve the separation), they were often kept apart so fully by their slave-owners that neither this foundational human relationship nor its crucial influences on the children’s identities and lives were allowed to develop or flourish.

In the opening chapter of his monumental Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, An America Slave, Written by Himself (1845), escaped slave turned abolitionist activist Frederick Douglass recounts what such forced separations meant for his relationship with his mother: “I never saw my mother, to know her as such, more than four or five times in my life; and each of these times was very short in duration, and at night. … She died when I was about seven years old, on one of my master’s farms, near Lee’s Mill. I was not allowed to be present during her illness, at her death, or burial. She was gone long before I knew any thing about it. Never having enjoyed, to any considerable extent, her soothing presence, her tender and watchful care, I received the tidings of her death with much the same emotions I should have probably felt at the death of a stranger.”

Despite Douglass’s narrative and other contemporary depictions of such horrors of slavery, in 1850 most white Americans were either unaware of or indifferent to slavery’s inhumane practices and effects. For many white Americans, of course, African American slaves were more property than full fellow humans, an attitude enshrined in the Constitution’s 3/5th clause and legally reified by the Supreme Court’s 1857 Dred Scott v. Sandford decision. Even for those Americans who were inclined to see slaves as human, there were a number of widespread narratives and myths that made it more difficult for white Americans to understand or be outraged about the horrors: slavery was a regional issue and largely unfamiliar to the rest of the nation; slaves were generally well treated and stories of horror were rare and overstated; slaves had never known other circumstances and were unaffected by situations and emotions that might impact other communities or cultures.

One of the most popular and influential American cultural works of all time would soon change those myths and perspectives for many Americans, however. On June 5, 1851, the abolitionist newspaper The National Era began publishing in weekly installments Harriet Beecher Stowe’s anti-slavery novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin; after a 40-week serialization, the novel was published in book form on March 20, 1852. Over the course of its serialization Uncle Tom’s Cabin became a national phenomenon (on the few occasions when Stowe missed a weekly issue the newspaper was inundated with letters of protest), and the success carried over into its publication: the book sold 3,000 copies on the day of its release, sold out its first printing almost immediately, and went on to become the second best-selling American book in the 19th century (after only the Bible) and one of the nation’s most enduring and influential cultural works.

Uncle Tom’s Cabin is a sizeable novel with many characters and plotlines, but at its heart are the stories of three slaves whose lives are consistently defined by family separations and their profoundly human effects. The loving couple (who define themselves as husband and wife, although they cannot be legally married under slavery) Eliza and George Harris learn that their beloved young son Harry is going to be sold away from them and choose to run away instead, producing a series of harrowing sequences such as Eliza and Harry’s famous escape across the icy Ohio River. And the title character Tom Shelby is sold “down the river,” away from his wife and children, and spends the rest of the novel trying to survive the horrors of slavery and find a way to be reconnected with that family. His famous connection with young Evangeline “Little Eva” St. Clare, the angelic daughter of his second owner, clearly serves as a replacement parental relationship for the patient and paternal Tom.

Stowe’s success in creating these deeply human slave characters and stories is the novel’s greatest achievement, made all the more impressive by the fact that she had spent no time in the slave south prior to writing the book (which she largely completed while living in Maine). Stowe did live for a time in Cincinnati, just across the Ohio River from the slave state of Kentucky, and encountered escaped slaves there as part of the city’s Underground Railroad efforts. She highlighted those and other contemporary influences on the novel — including the slave narrative The Life of Josiah Henson (1849) and Theodore Weld’s edited collection American Slavery as It Is: Testimony of a Thousand Witnesses (1839) — in her follow-up book A Key to Uncle Tom’s Cabin (1854).

Yet while those works do complement and support Stowe’s book, biographers and historians have discovered that she read many of them only after completing Uncle Tom’s Cabin. The novel was instead primarily a work of imaginative empathy, of constructing African American slave characters — and many others, but especially these central characters — with multi-layered human identities and perspectives that contribute to believable and moving stories of the horrors of the system of slavery. And Stowe’s empathetic imagination clearly produced the same effect for thousands of her fellow Americans, readers across the country for whom this cultural representation of slaves and slavery opened up new ways of thinking about the lives and experiences of their fellow Americans in bondage. Eliza, George, Tom, and others came to vivid life for Stowe’s readers, and through them new images of slavery and its defining savagery became possible and widespread.

While the novel remains an important part of 21st century American society, we have other cultural forms today that more closely mirror the immediacy of the 19th century novel’s communal impact: photography and photojournalism, multi-media news features, and social media activism. As we are seeing every day, such cultural forms help Americans imagine and respond to unfolding horrors. Where we go from there is, as it was in Stowe’s era, an open and crucial question.