The Making of the Cowboy Myth

It is rare to find cowboys on the silver screen who spend much time performing the humdrum labor — herding cattle — that gave their profession its name. Westerns suggest that cowboys are gun-toting men on horseback, riding tall in the saddle, unencumbered by civilization, and, in Teddy Roosevelt’s words, embodying the “hardy and self-reliant” type who possessed the “manly qualities that are invaluable to a nation.”

But real cowboys — who worked long cattle drives in lonely places like Texas — mostly led lives of numbing tedium, usually on the fringes of society. They were the formerly enslaved, poor farm boys, and downtrodden Native Americans. They enjoyed little autonomy on the trail. It was Hollywood, and men like Roosevelt, who whitewashed the cowboy, elevating him to the epitome of personal freedom, manly courage, and rugged independence.

For centuries, whether in the British Isles, the Iberian Peninsula, or the Americas, herding livestock to market put meat on the tables of city dwellers and money in the pockets of rural livestock owners. “Drove roads,” the term for routes through which livestock were driven, laced the countryside of rural England and Colonial America, connecting local communities to urban centers and generating millions of dollars in trade.

Herding cattle was considered beneath the dignity of respectable people.

While turning cattle into capital could be lucrative for livestock owners, herding this “cash on the hoof” remained the job of low-status workers. In southern Appalachia during the 18th and 19th centuries, “cow keepers” used whips and dogs to control their herds, and if the term “cowboy” was used it was almost certainly pejorative. During the same era, in Mexico, the task of herding cattle fell to vaqueros, a multiracial, low-status group who transformed what had been a pedestrian chore into an equestrian art. Their lazo (rope with a slip knot) became a lasso, chaparajos became chaps, and sombrero became the ten-gallon hat. Because vaqueros were largely of indigenous descent, one could say that all of these early cowboys were in fact “Indians.”

In mid-19th-century Texas, millions of cattle grazed the open range — and many Texans preferred to gather wealth in cattle, which multiplied every year, to amassing wealth in land. But the rough task of gathering and herding cattle was considered an occupation beneath the dignity of respectable people. Herders roamed the mesquite thickets, coastal savannahs, and brush lands of eastern Texas capturing and branding any cattle they could find, seldom bothering to determine an animal’s ownership before taking it to market. Texas newspapers warned against “this roving class of worthless characters” who “may forget that there is a distinction between ‘mine’ and ‘thine.’”

Things changed after the Civil War when Texans began driving longhorn cattle hundreds of miles to the railroads in Kansas, in what became the longest, largest forced migration of animals in history. In Texas a steer might sell for only a few dollars; in Kansas, where livestock could be transported by rail directly to stockyards in Chicago, it might bring $30 or $40.

Texans who could marry their backcountry herding skills to the entrepreneurial demands of the Gilded Age stood to make fantastic profits. Some of these successful Texas cowboys became leading symbols in the new Western myth. Charles Goodnight found instant fame when he teamed with renowned cattleman Oliver Loving, hired a crew of impoverished ex-Confederates and a formerly enslaved person named Bose Ikard, and pushed a herd through the west Texas desert into New Mexico and then north to Denver. Selling the animals at $60 per head, he returned to Texas with $12,000 in gold.

Still, what actually occurred on these long drives wasn’t glamorous. Cattle herding was no place for free thinkers or independent minds. Like any other industrial-age enterprise, the cattle drive was built around guiding principles of centralized control, monotonous routines, and a disciplined labor force. It was “systematically ordered,” as Goodnight said.

Driving two or three thousand cattle over 1,000 miles required a dozen or so cowboys, each with four or more horses, working for three to six months. The trail boss, who might be the ranch owner but was more likely an experienced ranch hand, rode ahead of the herd to control the pace and direction of travel and tolerated neither unruly cattle nor rebellious laborers. Cowboys took orders and worked for wages typically lower than skilled factory pay.

Despite the prevalence of lethal firearms and “Indian” fights in Western movies, there wasn’t much evidence of either in the actual cattle drives.

Each herder had a regular position in the herd, from lead to flank to swing to drag, with status and sometimes pay according to position. According to Montana cowboy Edward Charles “Teddy Blue” Abbott, drag riders had it the worst. Responsible for bringing along the poor, weak, or wounded animals, drag riders would end the day “with dust half an inch deep on their hats and thick as fur on their eyebrows,” Abbott said. Even worse was the dust in their lungs, which had them coughing up brown phlegm for months after the drive.

Most riders on the drives were out-of-work farmers’ sons, some as young as 12 years old, who saw the opportunity to trail cattle as both a rare paying job and a rite of passage. African-American cowboys earned less and were often required to take on more dangerous tasks. Vaqueros also worked the herds. Bosses recognized their superior roping and riding skills but paid them less than Anglo riders. A few women went up the trail, mostly as wives in wagons accompanying the herds. In 1888 a young girl named Willie Matthews disguised herself as a boy and worked, rode, and roped along with the rest of the crew.

These diverse workers, a proletariat on horseback, shared in the grinding monotony of the trail — and often said as much. According to 19th-century Kansas journalist Henry King, who interviewed many trail riders as they arrived in Dodge City, repetitious chores caused cowboys to feel “adrift on these great, vague, and melancholy prairies.” One cowboy complained, “The trip that was once so exciting and thick with adventure has come to be an unspeakably cheerless and tiresome thing.”

Even the food was monotonous: Beans and biscuits constituted the standard fare. While the cowboys were surrounded by beeves — as they called cattle destined to become meat — eating into the boss’s profit margin was not an option. According to 19th-century Kansas cattle buyer Joe McCoy, the unhealthy diet, along with a lack of tents, blankets, or even clean water, sapped the youthful vigor of cowboys and caused them to become “sallow and unhealthy” and “half-civilized only.” For some, “gloom” and “depression” descended on the crew until “conversation dwindled into monosyllables.” The legendary strong, silent type — so well known from so many classic movies — may have emerged from the unspeakable boredom of trail life.

Wearisome dullness was occasionally interrupted by the sheer terror of the stampede. Longhorns had a strong flight instinct, and a thunderstorm, an unexpected noise, or even the shake of a blanket could send them scattering. This sudden, unexpected, and seemingly aimless mass flight would shake the ground like an earthquake and crush any luckless herder caught in its path. At best, a stampede meant several days and nights of chasing after stray bunches of cattle. Combined with regular shifts of riding night duty, this meant that cowboys stayed in the saddle for three days or more. In such times coffee was not enough, Teddy Blue Abbott said. The only way to stay awake was to rub tobacco juice in one’s eyes.

For some cowboys, the hardest moments along the trail were the almost daily killings of newborn calves. Some herds were entirely steers (neutered males) headed for market, but others consisted of cattle of mixed sex, including pregnant cows. Newborn calves could not be tolerated because they slowed the herd. According to his biographer, Charles Goodnight said, “We killed hundreds of newborn calves on the bed grounds. I always hated to kill the innocent things, but since they were never counted in the sale of cattle the loss of them was nothing financially.” The duty to “murder the innocents” each morning typically was assigned to a lower-status worker, either one of the younger members of the crew or an African-American, who shot the calves dead. One such worker, Branch Isbell, became so disgusted with “being the executioner” that he swore off using or owning guns for the rest of his life.

Despite the prevalence of lethal firearms and “Indian” fights in Western movies, there wasn’t much evidence of either in the actual cattle drives. Many trail bosses required their workers to keep their pistols in the chuck wagon, for fear that gunshots would cause a stampede. A cumbersome six-shooter was heavy to wear and had no real use in most trail situations. And besides, carrying pistols in public was illegal in Texas settlements and in the Kansas cattle towns at the end of the trail.

The famous Chisholm Trail passed through Indian Territory in what is now Oklahoma, and some Native nations along the path, notably the Creeks, Cherokees, and Chickasaws, charged a fee for cattle crossing their land. Some Texas drovers claimed they fought back, and told manly stories of staring down the menace while brandishing their Winchesters. More commonly, however, they hired Native American cowboys to help herds across rivers or to find strays after a stampede. While the “Indian” threat loomed large in the Texas imagination, trail drives were marked more by cooperation than conflict.

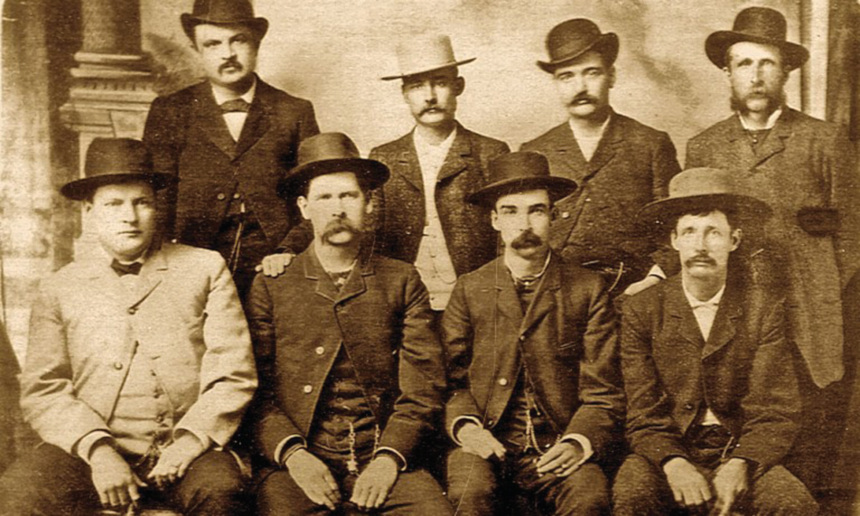

There was one way in which actual cowboys helped forge the cowboy myth — in the downtime herders enjoyed as soon as they arrived in Kansas cattle towns. After bathing and shaving, but before heading to the saloon, they traded in their homemade trail clothes — straw or felt hats, flannel shirts, durable pants — for what some called the “working costume” of the cowboy: ten-gallon Stetsons, fancy shirts, leather chaps, star-topped boots, and sometimes a fancy pistol. Thus styled, they went to the photographer, posing for photos that wound up in newspapers, galleries, and archives across the country.

This visual legacy is about as accurate as using high school prom pictures to portray the typical attire of today’s teenager. But it made an indelible impression. Through popular culture, fictional cowboys became the antidote to worrisome urbanization and soul-killing industrialization that Gilded Age Americans needed.

Buffalo Bill Cody borrowed the image of the heroic cowboy for his Wild West shows, choosing a trail rider from Texas, Buck Taylor, to perform riding and roping tricks for his Eastern audiences. Tall, lean, and handsome, Taylor quickly became known as “King of the Cowboys,” a moniker he kept when he became the model for dime novels in the 1880s, written in as little as 24 hours and sold to millions of Eastern readers seeking escape from the regimented world of cities and factories. The books, like later Hollywood Westerns, thrived on the notion of the cowboy as individualist and gun-toting adventure hero. They had no use for the monotony and hardship of a cattle drive — the real life of the cowboys.

This article originally appeared at Zócalo Public Square and is featured in the January/February 2020 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Featured image: Mild West? A decidedly unglamorous meal of beans after a long, dreary, dusty day on the trail. For the most part, cowboys consisted of poor farm boys, downtrodden Native Americans, and former slaves. (Detroit Photographic Co. / Library of Congress)

How Dodge City Became The Ultimate Wild West

Everywhere American popular culture has penetrated, people use the phrase “Get out of Dodge” or “Gettin’ outta Dodge” when referring to some dangerous or threatening or generally unpleasant situation. The metaphor is thought to have originated among U.S. troops during the Vietnam War, but it anchors the idea that early Dodge City, Kansas, was an epic, world-class theater of interpersonal violence and civic disorder.

Consider this passage from the 2013 British crime novel Missing in Malmö by Torquil MacLeod: “The drive to Carlisle took about 25 minutes. The ancient city had seen its fair share of violent history over the centuries as warring Scots and English families had clashed. The whole Border area between the two fractious countries had been like the American Wild West, and Carlisle was the Dodge City of the Middle Ages.”

So, just how bad was Dodge, really, and why do we remember it that way?

“A gentleman wishing to go from Wichita to Dodge City, applied to a friend for a letter of introduction. He was handed a double-barreled shotgun and a Colt’s revolver.”

The story begins in 1872, when a miscellaneous collection of a dozen male pioneers — six of them immigrants — founded Dodge astride the newly laid tracks of the Atchison, Topeka, and Santa Fe Railroad. The town’s early years as a major shipping center for buffalo hides, its longer period as a “cowboy town” serving the cattle trails from Texas, and its easy accessibility by rail to tourists and newspaper reporters made Dodge famous. For 14 years, the media embellished the town’s belligerence and bedlam — both genuine and created — to produce the iconic Dodge City that was, and remains, a cultural metaphor for violence and anarchy in a celebrated Old West.

Newspapers in the 1870s crafted Dodge City’s reputation as a major theater of frontier disorder by centering attention on the town’s single year of living dangerously, which lasted from July 1872 to July 1873. As an unorganized village, Dodge then lacked judicial and law-enforcement structures. A documented 18 men died from gunshot wounds, and newspapers identified nearly half again that number as wounded.

But the newspapers didn’t merely report that news: They interwove it with myths and metaphors of the West that had emerged in the mid-century writings of Western travelers such as Frederick Law Olmsted, Albert D. Richardson, Horace Greeley, and Mark Twain, and in the “genteel” Western fiction of Bret Harte and its working-class counterpart, the popular yellow-back novels featuring cowboys, Indians, and outlaws.

Consequently, headlines about seriously lethal doings in Dodge echoed the make-believe West: “BORDER PASTIMES. THREE MEN BORED WITH BULLETS AND THROWN INTO THE STREET”; “FROLICS ON THE FRONTIER. VIGILANTES AMUSING THEMSELVES IN THE SOUTHWEST … SIXTEEN BODIES TO START A GRAVEYARD AT DODGE CITY”; “TERRIBLE TIMES ON THE BORDER. HOW THINGS ARE DONE OUT WEST.”

One visiting reporter remarked that “The Kansas papers are inclined to make mouths at Dodge, because she has existed only one month or thereabouts and already has a cemetery started without the importation of corpses.” Another quipped, “Only two men killed at Dodge City last week.” A joke circulated among Kansas weeklies: “A gentleman wishing to go from Wichita to Dodge City, applied to a friend for a letter of introduction. He was handed a double-barreled shot-gun and a Colt’s revolver.”

The bad news out of Dodge made its major East Coast debut in 10 column inches in the nation’s then most prestigious newspaper, the late Horace Greeley’s New York Tribune. Titled “THE DIVERSIONS OF DODGE CITY,” it condemned the village for the lynching of a black entrepreneur. “The fact is that in charming Dodge City there is no law,” it concluded. “There are no sheriffs and no constables. … Consequently there are a dozen well-developed murderers walking unmolested about Dodge City doing as they please.”

Conditions of well-publicized anarchy, though they sold out-of-town papers, were not what Dodge City’s business and professional men wanted. From the town’s founding they had feared more for their pocketbooks than for their lives. Their investments in buildings and goods, to say nothing of the settlement’s future as a collective real-estate venture, stood at risk. For their common business enterprise to pay off, they had to attract aspiring middle-class newcomers like themselves.

And so, in the summer of 1873, Dodge’s economic elite wrested control of the situation. The General Land Office in Washington at last approved its group title to the town’s land, and the electorate chose a slate of county officers, of whom the most important was a sheriff. Two years later, Kansas granted Dodge municipal status, authorizing it to hire a city marshal and as many assistant lawmen as needed.

From August 1873 through 1875, apparently no violent deaths occurred, and from early 1876 through 1886 (Dodge’s cattle-trading period and during its ban on the open carry of sidearms), the known body count averaged less than two violent deaths per year, hardly shocking. Still, the cultural influence of that infamous first year has colored perceptions of the settlement’s frontier days ever since. Part of the reason was a Swedish immigrant, Harry Gryden, who arrived in Dodge City in 1876, established a law practice, inserted himself into the local sporting crowd, and within two years began penning sensationalist articles about the town for the nation’s leading men’s magazine, New York’s National Police Gazette, known as the “barbershop bible.”

In 1883, a Dodge City reform faction briefly assumed control at City Hall and threatened to start a shooting war with professional gamblers. Alarmist dispatches, including some by Gryden, circulated as Associated Press stories in at least 44 newspapers from Sacramento to New York City. The Kansas governor was preparing to send in the state militia when Wyatt Earp, arriving from Colorado, brokered a peace before anyone got shot. Gryden, having already introduced both Earp and his friend Bat Masterson to a national readership, penned a colorful wrap-up for the Police Gazette.

With the end of the cattle trade at Dodge in 1886, its middle-class citizenry hoped that its bad reputation would at last subside. But interest in the town’s colorful history never disappeared. This enduring attention eventually led to Dodge’s inauguration in 1902 as a staple item in the upscale mass-circulation magazines of the new century, including the very widely read Saturday Evening Post.

With that, the dangers of Dodge became a permanent commodity — a cultural production that was retailed to a primary market of tourists, and wholesaled to readers and viewers. Thereafter, writers catering to the public’s fascination with the town’s violent reputation seemingly tried to outdo one another in lurid generalizations: “In Dodge … the revolver was the only sign of law and order that could command respect.” And: “The court of last resort there was presided over by Judge Lynch.” And: “When one was ‘bumped off,’ the authorities just hustled the body out to Boot Hill and speculated upon what else the day would bring forth in bloodshed.”

Dodge’s local handful of yarn-spinners endorsed such nonsense, and bogus estimates of those interred on Boot Hill ranged from 81 to more than 200. By the 1930s, the town’s consensus had settled on 33, a number that included victims of illness as well as violence — but a best-selling biography of Wyatt Earp, published in 1931 by the California writer Stuart Lake and still in print, boosted the body count back up to 70 or 80. Lake’s book’s success, a burgeoning auto-borne tourism, and the Great Depression’s severe economic effect on southwest Kansas collaborated in wiping out any remaining local resistance to memorializing Dodge City’s bygone days.

Writers catering to the public’s fascination with the town’s violent reputation seemingly tried to outdo one another in lurid generalizations.

Movies and then television also got into the act. As early as 1914, Hollywood had discovered the old frontier town. In 1939 Dodge got major film treatment. But it was a TV series set in Dodge that ensured its continuing cultural importance. Gunsmoke entertained literally millions of Americans for a phenomenal 20 years (1955-1975), becoming one of the longest-running prime-time serials ever aired. Ironically, because the hour-long weekly program appears to have prompted the “Get outta Dodge” trope, the population of Hollywood’s Dodge was an interesting soap-opera collaborative of reasonable citizens beset with weekly onslaughts of assorted trouble-making outsiders. It was a dangerous place only because of the people who did not live there.

Imaginary Dodge is still hard at work helping Americans chart their moral landscape as the archetypal bad civic example. Inserted into the national narrative, it promotes belief that things can never be as dreadful as they were in the Old West, thereby confirming that we Americans have evolved into a civilized society. As it reassures the American psyche, the Dodge City of myth and metaphor also incites it to celebrate a frontier past brimming with aggression and murderous self-defense.

Originally published at Zócalo Public Square. This essay is part of What It Means to Be American, a project of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History and Arizona State University, produced by Zócalo Public Square.

This article is featured in the May/June 2019 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Featured image: Shutterstock

Beyond The Canvas: The Myth of The American West

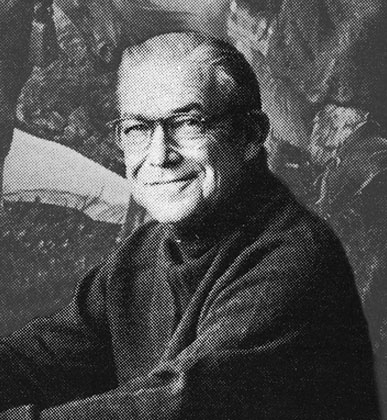

John Clymer

The Saturday Evening Post

There are few Post cover artists who so appreciated the American west as much as illustrator John Clymer. Born in the Pacific Northwest in Ellensburg, Washington, the artist grew up with vast landscapes of mountains and untouched plains reaching to the horizons.

America’s natural terrain charmed Clymer from a young age. He was taken by the mythos of the American west, of cowboys and Indians, and the thrill of adventure.

Clymer’s September 13, 1952 cover, “Herding Horses,” embodies the spirit of the American west. In this depiction, a rancher herds his livestock, fording them across a river on the plains. With his own young daughter saddled behind him, the cowboy smiles down on a colt struggling to navigate the waters.

The composition of the painting gives equal focus to the bounty of the surrounding natural elements, as well as the human involvement in living off the land. The top half of the work shows the snow-capped mountains in the distance complete with rolling hills and forest beneath. Sprinkled throughout are the farmsteads of ranchers and farmers who live off the land.

The artist’s decision to use the American Mustang for the river-crossing livestock instead of cattle or oxen adds to the overall wild and untamable nature of the American west. A feral horse that interbred with the European thoroughbred, it became a wild animal on the American plains. Their spots are a noticeable feature of their uncontrolled breeding in the wild. Note that Clymer’s rancher chooses to ride the most spotted mustang of the group rather than a monochrome horse of his herd. This symbolizes the cowboy’s ability to tame the Wild West.

Clymer used a vibrant color pattern to expose the beauty of nature and the change of seasons. A master of illustration who studied under N.C. Wyeth, Clymer shows off his artistic finesse in the clarity of the stream. His ability to successfully illustrate clear water, the rocks beneath, and the horses’ shadows upon the ripples is a testament to his artistic daring.

In fact, Clymer’s well-rounded training is evident throughout the entirety of the work. He is capable of drawing humans, as is evidence by the man and child on horseback. He flawlessly composes the equine trot, one of the most difficult animal forms in motion.

John Clymer was a master of his genre, and his passion for the land translates well onto canvas. Today, his work is well respected and highly lauded by western art museums and societies across the country. His artwork not only maintained but enhanced the myth of the American west. Many of his original paintings and illustrations are on display at the Clymer Museum of Art in Ellensburg, Washington.