Rationing Christmas: When Americans Had Money, But Nothing to Spend It On

1942 would have been a great Christmas, if it hadn’t been for the war.

Unemployment had dropped to 4%. Just nine years earlier it had been 25%, and the average annual income was $5,133. Now it was $9,900. And with the demand for workers in defense plants, many women had become breadwinners, supplying households with two paychecks for the first time.

Americans had never seen such prosperity. But of course, any pleasure they might have felt was dimmed by their worries about the war, and about relatives and friends whose lives were at risk every day.

Moreover, despite the economic boom, the holiday season was affected by new shortages. Ironically, a generation where many had grown up impoverished now had the money to buy the food and luxuries they wanted — but much of what they wanted was in short supply, rationed, or just not being sold.

Click to Enlarge

Here were a few items people had to go without:

Christmas cookies

Butter was in short supply and sugar rationing limited consumers to a pound of sugar every other week, which cut into Christmas treats.

Cigarettes

In 1942, the average American smoked a pack of cigarettes a day. But now a third of American cigarettes had been requisitioned by the armed forces. Smokers were often confronted with “No Cigarettes” signs in stores.

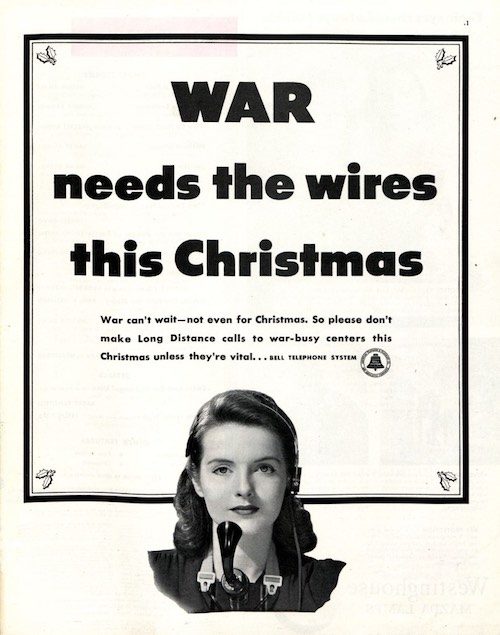

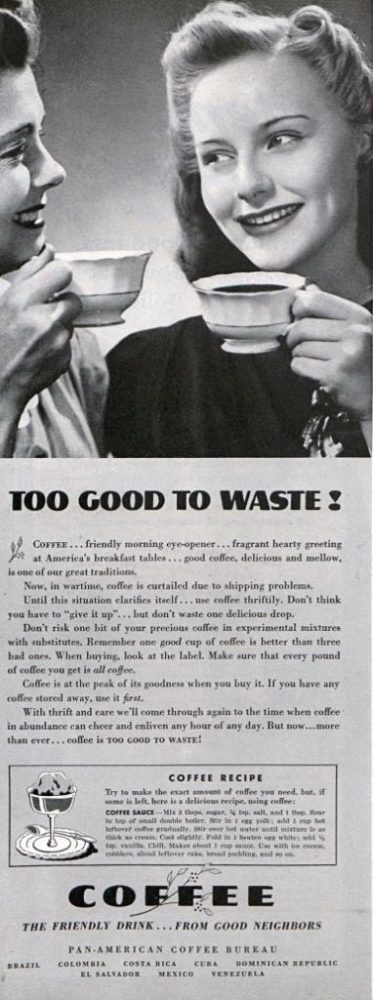

Coffee

The Office of War Production began coffee rationing in November of 1942. Americans could only purchase one pound of coffee every five weeks. For some, this was a third of their normal intake. And this was in a time when average coffee consumption was twice what it is today.

Click to Enlarge

Food

Consumers could only buy 2.5 pounds of red meat per week. Turkey, being a white meat, wasn’t rationed, but could be hard to find since the military requisitioned most of the country’s supply to provide turkey dinners for Christmas. In fact, because of hoarding, stores had trouble keeping all sorts of food, even items that weren’t rationed, available. Some stores themselves began rationing canned goods to prevent hoarding.

Travel

Starting in December of 1942, most motorists could only buy four gallons of gas a week. That limited family travel to approximately 68 miles a week, which might not have gotten them to Grandma’s and back at Christmas. People could still travel by train, but seats were limited because the railroads gave priority to military personnel.

Gifts

Store shelves weren’t exactly crowded that Christmas season. The big names in watches, radios, and other appliances were mostly producing military equipment. Other manufacturers could only get enough metal for limited production of gift items. Even simple items like bobby pins were hard to find. Consumers couldn’t even buy metallic tubes of toothpaste without first returning their old tube. Paper was also limited, which meant fewer books and magazines. Even clothing was in short supply. To conserve fabric, the War Production Board prohibited the sale of pleated skirts for women and double-breasted suits and vests for men.

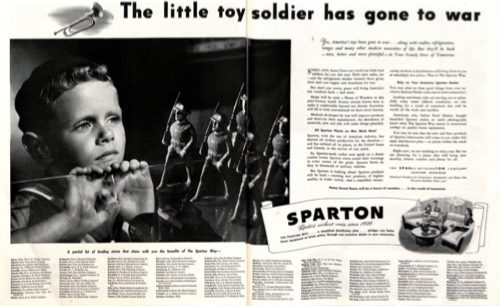

Toys

Toymakers couldn’t obtain the metal and rubber they normally used, so they improvised. They made dolls, trucks, airplanes, and construction sets from cardboard, or experimented with the new plastics. The Treasury Department acknowledged the toy shortage, but recommended that parents buy their kids War Bonds, which were, of course, in plentiful supply. Many parents made toys out of household materials, or cleaned up recycled toys shared by other parents.

Click to Enlarge

But Americans adapted to shortages. They found renewed pleasure in crossword puzzles, cooking, and parlor games. Women revived their sewing and dressmaking skills. As one historian wrote, Americans of 1942 “got to know their neighbors better. Social life improved noticeably. Pleasures became simpler and less frantic.”

Call of Beauty: Rationed Fashion on the Home Front

By the time Americans entered World War II after the attack on Pearl Harbor, they had already been feeling the effects of shortages.

Gas was still available in the fall of 1941, but gas stations were reducing their hours of operation to help conserve energy.

New cars weren’t in short supply yet, but automakers were reducing their production of passenger cars to build more airplanes and tanks. Businesses were warning Americans to take better care of their cars because it might be a long time before they could be replaced.

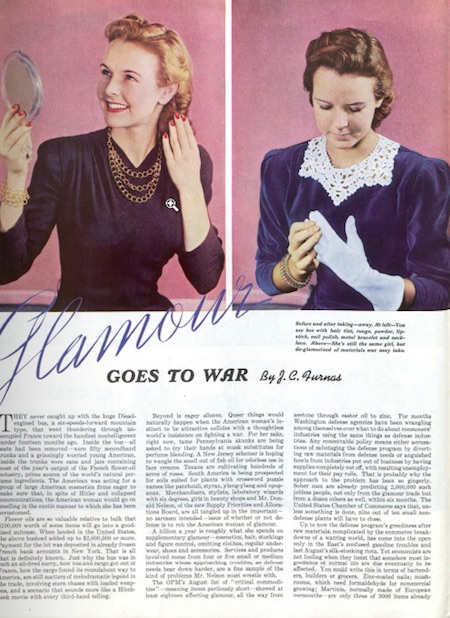

Of all the industries affected by the war, though, none brought the effect of war closer to Americans than the glamour business.

As J. C. Furnas points out in his November 29, 1941, article, “Glamour Goes to War,” American women were coping with shortages of cosmetics and stockings well before 1941. Embargoes and blockades halted the export of essential perfume oils from France, Bulgaria, Tibet, and Zanzibar. Necessary ingredients for lipstick and hair dye were no longer available from warring nations. Chemical solvents in nail polish were being requisitioned for military purposes. Even the brass used for lipstick containers was in short supply.

Almost all available silk had been purchased by the Defense Department to make parachutes and tents. Nylon stockings should have been the economical alternative. They had been introduced in May 1940, and 64 million pairs had been sold within the first year. But the raw materials of nylon were being used in the war effort, and women who wanted to avoid a bare-legged look were painting seams up their calves.

When the military began buying up the market supply of textiles, the fashion industry responded to the shortages by using less fabric in dresses. Hemlines went up and unnecessary detailing was dropped.

When cosmetics began to disappear, there was no matching movement to cut back on lipstick and powder. European perfume ingredients were replaced with synthetics, and whale spermaceti used in lipstick was swapped for more domestic lubricants.

Women continued to pursue the conventionally feminine image, even when operating heavy machinery in a B-17 plant. Advertisers encouraged this attitude, telling women it was their patriotic duty to maintain their looks for their men in uniform. The author himself warns that “many women, deprived of the usual makings of charm, would lose the personal self-confidence that helps bolster them through the ills of life.” The thought of 40 million women “reverting to Nature” made everyone jittery.

Much of the article is addressed to the “man of the house,” suggesting that his wife shouldn’t panic over the shortage. She may not have heard his reassurances, having already left for work at the munitions plant.

Featured image: Photos by Constance Bannister for “Glamour Goes to War,” from the November 29, 1941, issue of the Post.

America’s Wealth Gap

Will 2012 go down in history as the year money took over politics? Both parties will have spent more than a billion dollars electing the next president. More and more of that money comes from a handful of the wealthiest Americans and the corporations they run. On the Democratic side, Jeffrey Katzenberg of DreamWorks, telecommunications pioneer Irwin Mark Jacobs, and hedge fund manager James Simons have donated millions to re-elect the president, but the amount of money the Democrats have received from deep-pocketed supporters pales in comparison to what Republicans have received. A single billionaire, business magnate Sheldon Adelson, had by August spent more than $41 million and promised to spend up to $100 million defeating President Obama and other Democrats. All told, the top .07 percent of donors give more money than the bottom 86 percent. And it pays off. Candidates spend ever more time courting the super rich and then, once in office, try to keep them happy. This summer, for example, Mitt Romney held two fundraisers at which he raised almost $10 million from the oil and gas industry and then announced that as president he would end more than 100 years of federal restraint of oil and gas drilling on public lands. Things like that happen on both sides. How did we get into such a situation? What is to be done about it? Is it threatening our democracy? And doesn’t it go against everything the founding fathers stood for?

Those are big questions. The last one is the easiest to answer. Control of government by the richest wouldn’t have bothered the founders at all. It was just what they believed in. John Jay, the first Chief Justice, put it most directly: “The people who own the country ought to govern it.”

Many of the founders, including George Washington and Thomas Jefferson, were themselves among the wealthiest people in the country. They felt their prosperity made them obliged to serve their nation at the highest level. Yes, they declared independence and fought a Revolution to escape the tyranny of English monarchy and might, but they expected to replace aristocracy of birth with aristocracy of accomplishment, rule by elites who had created their wealth and influence, not inherited it. That was why they wrote a Constitution that stated the president was to be elected not by the people but by an elite Electoral College, and the Senate was to be chosen not by the people but by state legislatures. And that was why in most states only men who had money and property were allowed to vote at all.

It didn’t take long for the 99 percent of the day to rebel against that status quo. The notion of true democracy, rule by ordinary people, grew popular in the early 19th century. It was spearheaded by President Andrew Jackson, who hated bankers and banks, especially the national bank that had been founded by Alexander Hamilton. He destroyed the bank, partly to counter the power of the richest Americans. At the same time, a new generation of wealthiest Americans emerged, and they were a breed that had never existed in Europe—industrious, self-made men of humble origins, such as John Jacob Astor, a German immigrant who began working in a menial job for a fur merchant but came to dominate the trade in furs from the West, and Cornelius Vanderbilt, who rose from ferryboat captain to steamboat owner and then railroad baron. In 19th century America, the wealthiest really did have something in common with the common man.

Or at least that was true in the American North. The elite of the South were a breed apart. They grew fantastically rich and powerful from growing rice and cotton with all the hardest labor done by slaves. Seven of the first 12 presidents were from Virginia, the most prosperous part of the South. When the Civil War came, it was a fight not only over slavery but between the power of new Northern industry and urban wealth and the spoils of the Southern slave economy as well.

As extreme as the power of the wealthiest is today, it pales before that of the rich in the pre-Civil War South, for they could own human beings who had no rights whatsoever. Slave owners had such full support of the law that the Constitution originally counted each slave as three-fifths of a man for voting purposes, not so that slaves themselves could vote, but to add to the headcounts on which Congressional districts were based, giving their owners even more political and electoral power than anyone who didn’t keep slaves. Slavery was by far the highest point of the tyranny of the wealthiest in the United States.

But the kind of abuse of power that’s more familiar to us today took off after the Civil War, when four years of bloodshed costing more than a million lives left the South crippled and the North as a new industrial world power. That power corrupted, as it always does. The Gilded Age—which lasted from the end of the Civil War to 1900—was a festival of power grabs among the wealthiest. For instance, to build the Transcontinental Railroad, the owners of the Union Pacific Railroad set up a construction firm called Credit Mobilier to wildly overcharge for the work it did, just so they could bleed their own company and bondholders. Then, to make sure Congress didn’t complain, they gave assorted Congressmen both cash bribes and stock that paid huge dividends. The scam got exposed in 1872. It was estimated to have stolen $42 million in government and bondholder money, and it led to the disgrace of public figures as high up as the vice president, Schuyler Colfax.

By the 1880s the Senate was dominated by millionaires. And by 1892, wealth-fed scandal had become so commonplace that opposition to it gave rise to a new political party, the Populists, whose platform announced, “We meet in the midst of a nation brought to the verge of moral, political, and material ruin. Corruption dominates the ballot-box, the Legislatures, the Congress, and touches even the ermine of the bench. … The fruits of the toil of millions are boldly stolen to build up colossal fortunes for a few. … From the same prolific womb of governmental injustice we breed the two great classes—tramps and millionaires.”

When Theodore Roosevelt became president in 1901, he ushered in the Progressive Era, one of two major periods in U.S. history when the political tide turned strongly away from the wealthiest—the other was during the presidency of his distant cousin Franklin Roosevelt. Roosevelt railed against what he called “malefactors of great wealth” and the “criminal rich,” and he pushed through reforms like strengthened railroad regulations and the creation of the Department of Labor. A decade later, President Woodrow Wilson cemented Roosevelt’s accomplishments by establishing the federal income tax and the direct election of senators.

We know now that Government by organized money is just as dangerous as Government by organized mob.

Though none of that prevented the wild financial bubble fed by coziness between the wealthy and the government in the 1920s. So in the wake of the Great Crash that followed, Franklin Roosevelt took office in 1933 as a rich New Yorker determined to look out for the common man. He wrote to a friend, “The real truth of the matter is, as you and I know, that a financial element in the larger centers has owned the Government since the days of Andrew Jackson. … The country is going through a repetition of Jackson’s fight with the Bank of the United States—only on a far bigger and broader basis.” He raised taxes on the rich and used much of the money that came in to put the unemployed poor back to work. In 1936 he wrote: “We know now that Government by organized money is just as dangerous as Government by organized mob. … I should like to have it said of my first Administration that in it, the forces of selfishness and lust for power met their match. I should like to have it said of my second Administration that in it these forces met their master.”

Did We Mortgage Our Identity? The 1960s Worries About Conformity

By the 1950s, it was clear the 20th century wasn’t going to be the era of peace and prosperity Americans had predicted in 1900. It had brought them a world war, a major depression, and another world war, and now an interminable cold war. Americans were getting tired of the constant belt-tightening and war preparedness; they wanted to enjoy the society they’d built. But many were disappointed with the society they found. There was a general sense that things could, and should, be better.

Even if Americans didn’t feel a troubling malaise, the media certainly made a case for it. Journalists continually wrote of problems in American society, such as racism, alienation, and materialism. They also referred to the problem of “conformity.”

There was no single definition of the term. Popular magazines and television talked of conformity as the desire to fit in: Americans, like their milk, were becoming homogenized. They were abandoning their individual differences to fit in and get ahead. A popular song of 1962, “Little Boxes,” talked of people, their lives, and their “ticky tacky” houses all looking the same. But conformity was more than just the desire to accommodate the mainstream of America.

Between 1959 and 1963, three authors, each highly regarded for his insight and judgment, weighed in on the subject.

Erich Fromm, the renowned psychologist and philosopher, wrote “Our Way Of Life Is Making Us Miserable” in 1964. The need to conform, he said, didn’t arise in Americans but in their organizations, which rewarded people…

who cooperate smoothly in large groups, who want to consume more and more, and whose tastes are standardized and can be easily influenced and anticipated. It needs men who feel free and independent, yet who arc willing to be commanded, to do what is expected to fit into the social machine without friction; men who can be guided without force, led without leaders, prompted without an aim except the aim to be on the move, to function, to go ahead.

Our society is becoming one of giant enterprises directed by a bureaucracy in which man becomes a small, well-oiled cog in the machinery. The oiling is done with higher wages, fringe benefits, well-ventilated factories and piped music, and by psychologists and “human-relations” experts; yet all this oiling does not alter the fact that man has become powerless, that he does not wholeheartedly participate in his work and that he is bored with it.

[We should give Fromm credit for recognizing his profession might be enabling the system by helping citizens endure an unfriendly system.]

The ‘organization man’ may be well fed, well amused and well oiled, yet he lacks a sense of identity because none of his feelings or his thoughts originates within himself; none is authentic. He has no convictions, either in politics, religion, philosophy or in love. He is attracted by the “latest model” in thought, art and style, and lives under the illusion that the thoughts and feelings which he has acquired by listening to the media of mass communication are his own.

He has a nostalgic longing for a life of individualism, initiative and justice, a longing that he satisfies by [watching cowboy movies.] But these values have disappeared from real life in the world of giant corporations, giant state and military bureaucracies and giant labor unions.

He, the individual, feels so small before these giants that he sees only one way to escape the sense of utter insignificance: He identifies himself with the giants and idolizes them as the true representatives of his own human powers, those of which he has dispossessed himself.

Such ideas aren’t particularly surprising, coming from a humanist and psychologist. But much of what he says was echoed by other Post contributors in the early 1960s, including a social critic from an unexpected quarter.

12 Innovations That Changed Our World

The United States is an innovative nation fascinated by new ideas and impatient for improvement. Innovation is a line that weaves throughout our history—an electrified kite string that becomes a high-voltage power line, a telegraph wire, an optical phone cable, and an antenna that eventually dissolves into a cloud of wireless information. Innovation is a view of our country from a speeding car, a 75th floor office suite, a commercial flight at 30,000 feet, or a lunar craft 230,000 miles from home.

More than any single individual, invention, technology, or improvement, true innovation is an ever-evolving process—the product of unfenced thinking and hard work.

The Post salutes the past, present, and future innovations that shape the way we live, work, and play.

1. Capturing Lightning

Benjamin Franklin was the first major innovator in America. Through his experiments and writings, he educated the world on the nature of electricity, how it was conducted, and how it might be stored. He also helped reconcile religious leaders to scientific truths. As Post writer and historian Samuel Eliot Morison observes, before Franklin, “it was generally supposed to be immoral to assert a scientific cause for phenomena such as earthquakes, shooting stars, and thunder and lightning. Thus, Franklin’s proof of electricity’s causing lightning … took out of the field of religion something earlier classified as a mere act of God and included it in natural science.” Franklin’s work as a diplomat for science inspired other Americans to wrestle new destinies from the elemental forces.

A pioneer in many fields, Nikola Tesla developed alternating-current technology — considered one of the greatest discoveries of all time by many — to supply power to factories. His breakthrough enabled electricity from a power plant to travel over long distances, reaching far into the country, instead of being restricted to the few blocks around a power plant. Later, in the 1960s, physicists Bardeen, Brattain, and Shockley developed a replacement for the electronic vacuum tube. Their transistor, a small and simple device, marked the beginning of solid-state electronics and much smaller appliances. Televisions were no longer the size of washing machines. Portable radios could be hidden in a pocket. And computers shrank from the size of buildings to something that could slip down between the couch cushions.

2. Global Conversation

Samuel Morse wasn’t the only inventor working with telegraphy. But he was the first to offer a reliable, working system. In 1844 he demonstrated its efficiency in Washington by conversing with his associate in Baltimore 30 miles away. By the 1870s, Washington was telegraphing news to San Francisco, 2,400 miles away — a distance that required 60 days by coach. Years passed before Americans fully realized his accomplishment of removing the physical limits of exchanging thoughts. Communication traveled faster than the swiftest carriage or train. People could move ideas as quickly as they could think them.

As telegraph lines rose across the country, Alexander Graham Bell was filing his patent for a device to transmit the human voice. Early users felt shy about shouting into a receiver and listening through the static for a shouted reply, knowing that anyone in the neighborhood could quietly lift a handset and listen in. By the 1980s, this shyness had disappeared when Americans adopted Martin Cooper’s cellular phone. Telephone receivers shrank in size from a brick to a large earring, and it soon became hard not to listen to other people’s phone calls.

3. Americans Hit the Road

Henry Ford did not invent the automobile. His great innovation was introducing mass production to car manufacturing, launching an assembly line that enabled factory workers to build more than 18,000 cars in 1909. By 1920 Ford was selling about a million cars each year.

Americans adopted the automobile like a long-lost relative. People learned to drive, exploring the countryside and relocating when opportunity beckoned. They also began living farther from work, spawning the growth of suburbs.

America was expanding, both horizontally and vertically. Architect William Le Baron Jenney exchanged stone for metal frames and beams when he built Chicago’s Home Insurance Building in the 1880s. The 10-story structure weighed only as much as a three-story conventional building. Jenney’s success at 138 feet was doubled with the 285-foot Flatiron Building in 1902, and quintupled with the 1913 Woolworth Building. The horizon of cities rose and skyscrapers began dwarfing church steeples. In the wake of 9/11, few cities are planning to build skyscrapers that might draw the attention of terrorists. However, the Burj Dubai in the United Arab Emirates, upon completion, will reach 160 stories — half a mile high.

4. Illuminating the Country

While city dwellers ventured into the countryside, farm families migrated toward the city. Even though Thomas Edison regretted the shift, his work rendered it inevitable. Like most of his creations, the incandescent light bulb was a coincidental discovery. He discovered a workable filament for his light bulb by randomly trying thousands of materials before finding the answer in carbonized bamboo fiber.

With electric light, night lost its power to regulate Americans’ lives. Business operated around the clock. As Samuel Insull began building power plants across the Midwest, the faint glow of cities — once visible only in the eastern night sky — began to appear in the West.

Today, as cities grow brighter and the electric glow washes out the sky for miles, innovators are developing new light sources that cut down ambient lighting, focusing illumination where needed and reducing wasted light and energy demands.

5. Advent of Sound

American ingenuity was pushing back the silence of the frontier as well as its darkness. Edison discovered how to mechanically capture sound waves on wax and produced his “Ediphone,” which he intended to sell as a business dictation machine. Coincidentally, he discovered that his machine could record music.

True to form, Edison developed his sound machine through trial and error, without any underlying theory. And, just as typical, Edison stuck with his original ideas, using cylinder recordings — though discs were more practical — and personally selecting the music his studio recorded, despite his limited tastes and deafness in one ear.

Edison’s stubbornness created an opportunity that Eldridge Johnson seized when he founded the Victor Talking Machine Company. He brought a less expensive phonograph to the market and began recording a broader variety of music. His recording company achieved unimaginable success when, as an experiment, it began selling records of blues, jazz, gospel, and country music. The entertainment industry discovered a devoted following for music, a need largely ignored by polite society.

In the 1950s, engineers introduced long-playing records that offered more music with greater fidelity. At the same time, David Paul Gregg was busy working on his optical disc that used a laser to read audio data. Twenty years later, his development became the compact disc: a small, durable medium of complete fidelity that resisted scratches and static. Fifteen years later, the MP3 protocol compressed music into small computer files that could be transferred, stored, and played on miniature players. Today, Americans play more music than ever on personal MP3 players, which can be seen everywhere from the suburbs to the front lines in war.

6. Populating the Airwaves

As Edison pressed voices into wax cylinders, American scientists attempted to direct voices through the air. They experienced little success until Nikola Tesla, in 1895, developed the technology to transmit a sound signal from New York to West Point, 50 miles away. By the 1920s, radio amateurs were transmitting signals across the country and wracking their brains for broadcasting material. They read agricultural lectures, delivered sermons, relayed news from local papers, or played records. Several states away, enthusiasts fiddled with cat’s whiskers and coils on homemade sets, eager for any sound. Farm boys strung up wire to hear the talk and static of distant Chicago or New York.

Philo T. Farnsworth, a mathematical genius from Utah, successfully added a visual element to radio signals when he introduced the image dissector tube. The device, which he first built while in high school, enabled him to capture and transmit moving images. He broadcast America’s first television signal in 1927. The Radio Corporation of America eventually bought his patent and made the first public television broadcast from the 1939 New York World’s Fair. The first regularly appearing television show hit airwaves in 1947. Television stations struggled by on little revenue, and early programming favored cheap entertainment.

While some were critical of the quality of programming, no one could deny that televisions had become more sophisticated. Today, companies sell 150-inch, high-definition TVs and are developing contact lenses that transmit television shows.

7. Moving Pictures

America quickly realized that television could not replace its favorite form of entertainment: the movies. America’s motion picture industry was among the largest and most profitable in the world. Its earliest incarnation was Edison’s Kinetoscope: a hand-cranked viewer that showed a few minutes of dancing, gymnastics, or people simply walking down the street. Yet this humble beginning sparked an immense appetite for film.

Edison began work on a projector that allowed crowds to watch the same images. But Edison’s greatest contribution to the new industry was a curious little production called The Great Train Robbery. The 10-minute drama—crude, choppy, and over-acted—inspired other innovators with the possibilities of cinema.

No less remarkable was the innovation of George Eastman. His Kodak camera company encouraged Americans to take up what had been the expensive hobby of photography. Customers bought his camera, containing enough film for 100 images. After the film was exposed, the photographer mailed the entire camera back to Eastman’s laboratories, which sent back the pictures and a reloaded camera. Personal photography ceased being a rarity.

Now, with digital cameras, photographers are pushing the limits of what can be captured. High-definition displays and computer enhancement give photographs a level of detail that extends the capabilities of the human eye.

8. America Takes Flight

The Wright brothers approached flight with the enthusiasm of hobbyists, but realized they would have to master the science of aerodynamics. They built from the ground up, testing everything, and often finding their textbooks wrong. The brothers worked relentlessly against limited information and slim funds, crouching in a shack on the North Carolina coast, as 70 mph-winds tore against their machine. Finally, in December 1903, they succeeded. A half century passed before air travel became affordable.

Fascinated by the Wright brothers’ achievement, Americans failed to notice the work of another innovator. Robert Goddard grew up with a dream of traveling beyond Earth’s atmosphere, where aircraft could not depend on air resistance. Realizing that travel in the vacuum of space would require an engine to bring along its own oxygen, Goddard developed a rocket design that could carry its own fuel and created the multistage rocket that would jettison its own starter motor as it struggled against Earth’s gravity. In the 1930s, his research team was launching supersonic rockets 1.5 miles from earth. Almost predictably, he was discounted as a crackpot for talking about space travel, and the armed forces saw no military application in his missiles. Goddard died in 1945, just as America realized the vast potential of his work. Twenty-four years later, Americans crossed space, landed on the moon, and returned.

9. Tapping New Energy

Early in his career, Italian born Enrico Fermi realized it was possible to control the disintegration of uranium and start a chain reaction that would release massive energy. Working with physicist Leo Szilard, Fermi achieved nuclear fission for the first time in 1942. His research led to the development of an atomic bomb for the United States military. After dropping two atomic bombs on Japan, Americans became deeply concerned about this new, nuclear science. In 1946, a Post editorial warned: “If we are not destroyed by our own curiosity and rising standards of destructiveness, we could drift along, constantly testing the warlike possibilities in the atom until some other nation got the secret.” The remark was highly prophetic. Russia developed nuclear weapons in 1949. But Fermi hesitated to build a nuclear device with greater power, believing that such a device could only result in genocide.

America’s fears over nuclear disaster overshadowed promising applications such as nuclear medicine. Data from nuclear imaging has saved countless lives by detecting cancerous growths in their early stages. Another development, nuclear power generation, continues to face criticism. Despite Americans uneasiness about nuclear energy, nuclear reactors generate nearly 20% of our country’s electricity. Innovators are looking beyond the large nuclear plants to the potential of scaled-down reactors for neighborhoods or individual houses, which would be smaller than a garden shed.

10. Outsourcing Brainwork

While America’s attention focused on atomic power, a quiet innovation was underway that would prove even more powerful. George Stibitz was building a digital computer on his kitchen table. By 1940 the device could perform sophisticated mathematical calculations. While Stibitz used his computer to model biochemical systems in the human body, other innovators were looking at computer programs for more general interest.

Eventually, the personal computer (PC) made its debut in the late 1970s. At first a PC seemed as practical as a personal aerospace program. Yet innovators such as Apple’s Steve Jobs and Steve Wozniak developed affordable computers for everyday business operations. In 1979 the duo created an operating system that didn’t use advanced logic and computer language. This development, along with practical programs for word processing and spreadsheets, encouraged America to incorporate digital technology in their lives.

Thousands of tinkerers and hackers played with digital systems, often with only a burning curiosity to see what they could do. A man named Bill Gates aided the effort. His genius for programming and business helped him build the Microsoft Corporation. Not only did Gates assist America’s programmers in developing software, he helped standardize the industry so different systems could converse in a common operating system.

11. Computer Age

When Lawrence Roberts developed a system for sending data packets between computers, he had little idea where the innovation would lead. He developed his computer network—the ARPANET—for the government. At first university researchers began using the network to share data. Then the public discovered it.

Soon after, thousands of people around the world began creating documents and programs that could be freely shared through the World Wide Web. Millions of Web sites appeared on computer screens, offering phone directories, encyclopedias, political commentary, and access to a vast global marketplace that never closes. In the 1990s, Larry Page and Sergey Brin built Google, Inc. to help the world surf the rising ocean of information. Google would locate Web sites based on their titles or their contents, while also promoting new methods of sharing information — social networking, video sharing, music downloading, and free videophone service to anywhere in the world.

12. The American Voice

While all of these ideas shape the way we live, our greatest innovation is the rich and unique American culture — the confluence of our unique system of democracy, traditions, food, thought, language, and arts, over 20 generations, that has been exported, adopted, and imitated around the world.

From baseball to rodeos, Broadway musicals to demolition derbies, the Great American Novel to comic books, blue jeans to baseball caps, surfing in Malibu to singing at the Met, cooking in the French Quarter to dancing at the Zuni pueblo, American culture continues to shape the nature and pace of change around the globe.

But perhaps nothing reflects the wealth of American culture like our music. It borrowed from the home cultures of its people to produce a sound unique to the world. American music’s mixed ancestry imbued it with unexpected charm and vitality. More than just a fortunate hybrid, American music was based on the blues scale — one of the most significant innovations in Western music. The blues spun off new music traditions with a strong family resemblance. We hear the distinctive blues tonal progression in gospel, bluegrass, jazz, country, rock, soul, and pop music. The distinctly authentic sound of the country created a family connection between Americans as diverse as Bessie Smith, Glenn Miller, B.B. King, Bruce Springsteen, Aaron Copland, Otis Redding, Bob Dylan, Irving Berlin, and jazz legend Miles Davis.

The genius of the American experiment is stated in our motto “e pluribus unum”—out of many, one. Our American culture enables us to share roots, while encouraging experimentation and growth—out of many comes many more.

Illustrations by Britt Spencer.

President Obama to Speak at NAACP

A Proud Moment in a Long Struggle

President Obama will be in New York on July 16 speaking to a crowd of 10,000 people. While he has addressed much larger groups, rarely has he spoken on such a significant occasion: America’s first black president will be giving the keynote speech at the 100th birthday celebration of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP).

The NAACP was formed in 1909 to address a rising opposition to civil rights. Racism in America was discarding its subtlety, coming out in the open, and making a new bid for power. Southern legislators had enacted new laws that made it difficult, if not impossible, for black Americans to vote. Racial tensions ignited race riots, and more were coming.

Dr. W.E.B. DuBois edited the NAACP’s magazine, The Crisis, and helped frame the association’s goal:

“To promote equality of rights and to eradicate caste or race prejudice among the citizens of the United States; to advance the interest of colored citizens; to secure for the impartial suffrage; and to increase their opportunities for securing justice in the court, education for the children, employment according to their ability and complete equality before law.”

The early years were daunting and Washington extended little sympathy for the cause. The NAACP addressed the need to end official segregation, promote black men to officers in the military, and oppose the rising enrollment in the Ku Klux Klan. The effort met consistent opposition from southern legislators who blocked federal legislation against lynching.

Halfway through its first century, the NAACP was confronting racism as virulent as ever. Black Americans were achieving some of their goals, but they were also being accused of seeking their rights too aggressively.

Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.

Nov. 7, 1964

In the November 7, 1964, Post, Dr. Martin Luther King addressed this issue directly in his article, “Negroes Are Not Moving Too Fast.”

“Among many white Americans who have recently achieved middle-class status or regard themselves close to it, there is a prevailing belief that Negroes are moving too fast and that their speed imperils the security of whites. Those who feel this way refer to their own experience and conclude that while they waited long for their chance, the Negro is expecting special advantages from the government. It is true that many white Americans struggled to attain security. It is also a hard fact that none had the experience of Negroes. No one else endured chattel slavery on American soil. No one else suffered discrimination so intensely or so long as the Negroes. In one or two generations the conditions of life for white Americans altered radically. For Negroes, after three centuries, wretchedness and misery still afflict the majority.

“Anatole France once said, ‘The law, in its majestic equality, forbids all men to sleep under bridges—the rich as well as the poor.’ There could scarcely be a better statement of the dilemma of the Negro today. After a decade of bitter struggle, multiple laws have been enacted proclaiming his equality. He should feel exhilaration as his goal comes into sight. But the ordinary black man knows that Anatole France’s sardonic jest expresses a very bitter truth. Despite new laws, little has changed in his life in the ghettos. …

“Charges that Negroes are going ‘too fast’ are both cruel and dangerous. The Negro is not going nearly fast enough, and claims to the contrary only play into the hands of those who believe that violence is the only means by which the Negro will get anywhere. …

“A section of the white population, perceiving Negro pressure for change, misconstrues it as a demand for privileges rather than as a desperate quest for existence. The ensuing white backlash intimidates government officials who are already too timorous, and, when the crisis demands vigorous measures, a paralysis ensues. …

“Our nation has absorbed many minorities from all nations of the world. In the beginning of this century, in a single decade, almost nine million immigrants were drawn into our society. Many reforms were necessary—labor laws and social-welfare measures— to achieve this result. We accomplished these changes in the past because there was a will to do it, and because the nation became greater and stronger in the process. Our country has the need and capacity for further growth, and today there are enough Americans, Negro and white, with faith in the future, with compassion, and will to repeat the bright experience of our past.”

The NAACP has no reason to close operations this year. There is, alas, still more work ahead. However, we hope they, and the country, savor the moment when President Obama shares the podium with America’s first black secretary of state, Colin Powell, and our first black attorney general, Eric Holder. America should be very proud of this organization and the long dedication of its generations of members.