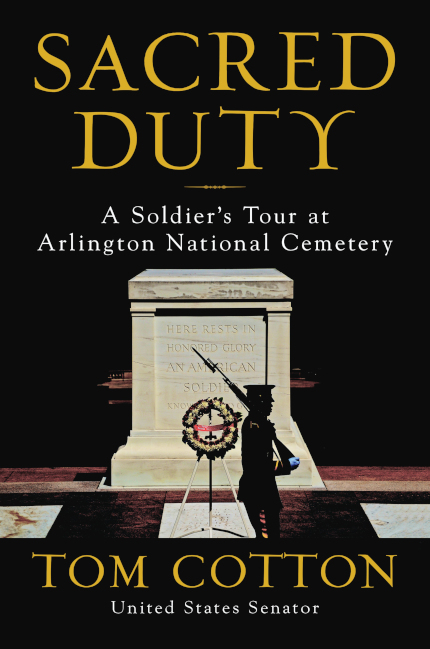

Sacred Duty

Every headstone at Arlington tells a story. These are tales of heroes, I thought as I placed the toe of my combat boot against the white marble. I pulled a miniature American flag out of my assault pack and pushed it three inches into the ground at my heel.

I stepped aside to inspect it, making sure it met the standard that we had briefed to our troops: “vertical and perpendicular to the headstone.” Satisfied, I moved to the next headstone to keep up with my soldiers. Having started this row, I had to complete it.

One soldier per row was the rule; otherwise, different boot sizes might disrupt the perfect symmetry of the headstones and flags.

I planted flag after flag, as did the soldiers on the rows around me. Bending over to plant those flags brought me eye-level with the lettering on those marble stones. The stories continued with each one. Distinguished Service Cross. Silver Star. Bronze Star. Purple Heart. America’s wars marched by. Iraq. Afghanistan. Vietnam. Korea. World War II. World War I. Some soldiers died in very old age; others still were teenagers. Crosses, Stars of David, Crescents and Stars. Every religion, every race, every age, every region of America is represented in these fields of stone.

I came upon the grave site of a Medal of Honor recipient. I paused, came to attention, and saluted. The Medal of Honor is the nation’s highest decoration for battlefield valor. By military custom, all soldiers salute Medal of Honor recipients irrespective of their rank, in life and in death. We had reminded our soldiers of this courtesy; hundreds of grave sites would receive salutes that afternoon. I planted this hero’s flag and kept moving.

On some headstones sat a small memento: a rank or unit patch, a military coin, a seashell, sometimes just a penny or even a rock. Each was a sign that someone—maybe family or friends, perhaps even a battle buddy who lived because of his friend’s ultimate sacrifice—had visited, and honored, and mourned.

For those of us who had been downrange, the sight was equally comforting and jarring—a sign that we would be remembered in death, but also a reminder of just how close some of us had come to resting here ourselves. I left those mementos undisturbed.

After a while, my hand began to hurt from pushing on the pointed, gold tips of the flags. There had been no rain that week, so the ground was hard. I questioned my soldiers how they were moving so fast and seemingly pain-free. They asked if I was using a bottle cap, and I said no. Several shook their heads in disbelief; forgetting a bottle cap was apparently a mistake on par with forgetting one’s rifle or night-vision goggles on patrol in Iraq. Those kinds of little tricks and techniques were not briefed in the day’s written order, but rather get passed down from seasoned soldiers. These details often make the difference between mission success or failure in the Army, whether in combat or stateside. After some good-natured ribbing, a young private squared me away with a spare cap.

We finished up our last section and got word over the radio to go place flags in the Columbarium, where open-air buildings contained thousands of urns in niches. Walking down Arlington’s leafy avenues, we passed Section 60, where soldiers killed in Iraq and Afghanistan were laid to rest if their families chose Arlington as their eternal home. Unlike in the sections we had just completed, several visitors and mourners were present. Some had settled in for a while on blankets or lawn chairs. Others walked among the headstones. Even from a respectful distance, we could see the sense of loss and grief on their faces.

Once we finished the Columbarium, “mission complete” came over the radio and we began the long walk up Arlington’s hills and back to Fort Myer. In just a few hours, we had placed a flag at every grave site in this sacred ground, more than two hundred thousand of them. From President John F. Kennedy to the Unknown Soldiers to the youngest privates from our oldest wars, every hero of Arlington had a few moments that day with a soldier who, in this simple act of remembrance, delivered a powerful message to the dead and the living alike: you are not forgotten.

The Thursday before Memorial Day is known as Flags In at Arlington National Cemetery. The soldiers who place the flags at every grave site in the cemetery belong to the 3rd United States Infantry Regiment, better known as The Old Guard. Since 1948, The Old Guard has served at Arlington as the Army’s official ceremonial unit and escort to the president.

I walked through Arlington for Flags In with The Old Guard in 2018. “What better way to show the nation and our fellow soldiers that we care and we never forget,” observed Colonel Jason Garkey, the regimental commander. As we walked along streets named for legends like Grant and Pershing, he added, “This mission is really important for The Old Guard, too. It’s the only day of the year when the whole regiment operates together. It gives all my soldiers—all my mechanics and medics and cooks—a chance to come perform our mission in the cemetery.”

Flags In carries a special meaning for our citizens, too, judging by our conversations that afternoon. Col. Garkey greeted every civilian who approached us. Most were curious about the soldiers they saw walking across the cemetery. As he explained Flags In and The Old Guard, without fail they expressed their fascination and gratitude. In Section 60, we encountered families and friends paying early Memorial Day visits to their loved ones. Col. Garkey thanked them for their sacrifice, and they thanked him for his service and for remembering their fallen heroes. He never mentioned that those were his soldiers or that he had planted flags that day at the graves of his own friends and mentors.

My turn at Flags In came in 2007 during my own tour at Arlington. I had joined The Old Guard a couple of months earlier, after serving a tour in Iraq with the 101st Airborne Division. My path to The Old Guard was unusual—like my journey into the Army itself.

It began the morning of 9/11 in a law-school classroom. In those days before smartphones, we did not learn that America was under attack until class ended, almost an hour after the first airplane hit the World Trade Center. But my life changed in that moment. I knew the life I had anticipated in the law was over.

I wanted to serve our country in uniform on the front lines. I finished school and worked for a couple of years to repay my student loans, time I also used to get prepared physically and mentally for the Army. It took my recruiter by surprise when I told him that I wanted to be an infantryman, not a JAG lawyer. To his credit, he signed me up and shipped me out, setting me on the path to Iraq. After more than a year in training, I joined the 101st in Baghdad in 2006, taking over a platoon of Screaming Eagles.

We conducted raids, laid in ambushes, dodged roadside bombs and sniper fire, and sorted out the dead in a vicious sectarian war. And at the end of that tour, to my surprise, the Army gave me orders to The Old Guard, even though I had not applied to the all-volunteer regiment. I knew The Old Guard was a special unit. The regiment has some of the highest eligibility standards in the entire military. Old Guard alumni were among the most squared-away soldiers I knew in the Army. And the mission set—not only conducting daily funerals in Arlington, but also world-famous ceremonies like presidential inaugurations and state funerals—called for the Army’s best soldiers, performing at the highest levels. I looked forward to the assignment and I felt honored while serving at Arlington.

But I did not fully appreciate our nation’s special reverence for The Old Guard and Arlington until years later, when I entered public life. A political newcomer, I spent the early months of my first campaign introducing myself to Arkansans, telling them about myself and what I hoped to accomplish for them. The most common question I got was not about Iraq or Afghanistan or about iconic Army institutions like Ranger School. No, the most common question, by far, was about my service with The Old Guard. The same holds true today; when I speak around the country to new audiences, questions about The Old Guard outnumber all the others. Likewise, thousands of Arkansans visit me each year in Washington. When I ask them about the highlight of their trip, Arlington tops the list.

The Old Guard embodies the meaning of words such as patriotism, duty, honor, and respect. These soldiers are the most prominent public face of our Army, perform the sacred last rites for our fallen heroes, and watch over them into eternity. The Old Guard represents to the public what is best in our military, which itself represents what is best in us as a nation.

As Old Guard soldiers, we viewed the funerals through their eyes as we trained, prepared our uniforms, and performed the rituals of Arlington. We held ourselves to the standard of perfection in sweltering heat, frigid cold, and driving rain. Every funeral was a no-fail, zero-defect mission, whether we honored a famous general in front of hundreds of mourners or a humble private at an unattended funeral.

Although funerals are The Old Guard’s highest-priority mission, the regiment also performs in ceremonies around the capital almost every day. From welcoming foreign leaders at the White House and the Pentagon to honoring retiring soldiers at Fort Myer, The Old Guard represents the discipline and skill of all soldiers. Among its ranks, The Old Guard boasts world-class musicians, the military’s most elite color guard, and the Army’s premier drill team. They carry the Army story and values to worldwide audiences and the smallest gatherings alike, always with pride and precision.

Arlington National Cemetery and The Old Guard transcend politics. We live in politically divided times, to be sure. Yet the military remains our nation’s most respected institution, and the fields of Arlington are one place where we can set aside our differences. Which itself is something of a historic irony, because our national cemetery was birthed in the most divisive time in our nation’s history, when Americans killed each other on such a mass scale that a farm across the river from our capital became the graveyard for those war dead. Perhaps because of those bloody origins, Arlington National Cemetery emerged from the ashes of the Civil War as a place dedicated to healing, reconciliation, and remembrance.

What the Old Guard does inside the gates of Arlington is a living testament to the noble truths and fierce courage that have built and sustained America. We go to great lengths to recover fallen comrades, we honor them in the most precise and exacting ceremonies, we set aside national holidays to remember and celebrate them. We do these things for them, but also for us, the living. Their stories of heroism, of sacrifice, of patriotism remind us of what is best in ourselves, and they teach our children what is best in America.

On the eve of the war that transformed this farm into a national cemetery, President Abraham Lincoln pleaded for unity in his First Inaugural. “Though passion may have strained, it must not break our bonds of affection,” he acknowledged, while appealing to the “mystic chords of memory, stretching from every battle-field, and patriot grave, to every living heart and hearthstone, all over this broad land.” In our days, as in his, passions can no doubt strain our bonds of affection, but those mystic chords of memory still stretch from the patriot graves of Arlington across our great land, calling forth yet again “the better angels of our nature.”

For the fallen and their families, The Old Guard honors their service and sacrifice. For us, the living, The Old Guard embodies our respect, our gratitude, our love for those who have borne the battles of a great nation—and those who will bear the burdens of tomorrow. No one summed up better what The Old Guard of Arlington means for our nation than did Sergeant Major of the Army Dan Dailey. He recalled a moment with a foreign military leader while driving through the cemetery to lay a wreath at the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier. “I was explaining what The Old Guard does and he was looking out the window at all those headstones. After a long pause, still looking at the headstones, he said, ‘Now I know why your soldiers fight so hard. You take better care of your dead than we do our living.’ ”

From the book “Sacred Duty: A Soldier’s Tour at Arlington National Cemetery” by Tom Cotton. Copyright © 2019 by Thomas B. Cotton. Reprinted by permission of William Morrow, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers.

Featured image: U.S. Army.

Honoring Our Heroes

Last Memorial Day, tens of thousands of Americans took the time to mourn and to recall the lives of fallen heroes and lost loved ones. Among these was Carla Sizer of Falcon, Colorado, whose 19-year-old son, Army Specialist Dane Balcon, was killed by a roadside bomb in Iraq in 2007.

“Dane, tomorrow is Memorial Day, and it is bittersweet,” Sizer wrote. “Bittersweet in that we miss you and love you … but so proud that you died in an honorable manner. It is my mission to ensure that you and others like you are never forgotten. Your legacy will live on forever; I promise … they won’t forget.”

Her sentiment was posted on Legacy.com, the largest of a growing number of websites that commemorate the men and women who give their lives in defense of the country. The Legacy.com page in Dane’s honor includes several obituaries, more than 200 photos, and a guest book with around 1,500 messages from relatives, friends, neighbors, and even strangers paying tribute to his service and sacrifice.

Like gravestones and monuments, virtual memorials are accessible year-round, but are positively thronged over the Memorial Day weekend—indicating just how important the day still is to Americans, notes John Metzler, superintendent of Arlington National Cemetery near Washington, D.C. “Memorial services and cemeteries won’t disappear, but how we remember someone, how we tell the story of a life—that’s changing fast, and is no longer limited to what can be carved on a gravestone or inked on newsprint,” he says.

It began with decorations

Memorial Day, our official holiday for the remembrance of those who die in military service, has been celebrated for nearly 150 years. But each new generation observes the day a little differently—based on the character of the era. Today the holiday has expanded beyond its official origins: Americans often use the day to remember not just servicemen and women, but all friends and family who have passed away. Watching parades and air shows, attending memorial ceremonies, placing flowers on graves, and even the basic practice of sharing memories with others are all part of this celebratory yet solemn day.

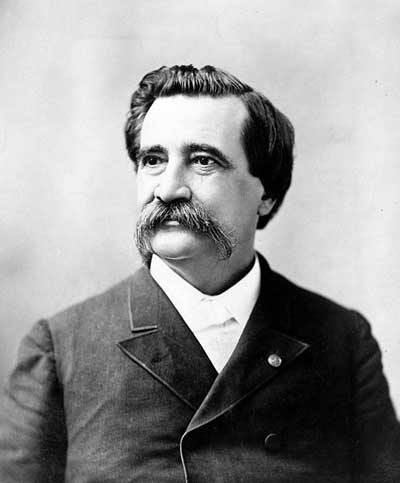

Originally known as Decoration Day, the official holiday was proclaimed by General John Logan, national commander-in-chief of the Grand Army of the Republic, on May 5, 1868, in response to national grief over the tremendous loss of life in the American Civil War. It was first observed on May 30 of that year with the decoration of grave sites at Arlington National Cemetery.

By 1890, all of the Northern states observed Decoration Day. However, due to lingering Civil War hostility, the South refused to take part until after World War I, when the holiday’s meaning was changed from honoring the Civil War dead, to honoring all Americans who had died in military service. Still, despite the change, several southern states, including Texas, Alabama, Florida, Georgia, Mississippi, South Carolina, Louisiana, and Tennessee, continue to observe a separate day of mourning known as Confederate Memorial Day or Confederate Heroes Day.

In 1966, President Lyndon B. Johnson officially changed the name of Decoration Day to Memorial Day and declared the city of Waterloo, New York, to be the original birthplace of the idea, but it is more likely that the practice evolved broadly. Today more than two dozen cities claim to be the real place of origin, but the genuine roots of the holiday may in fact remain in a page of history that up until recently had been forgotten. (See box for the full story.)

Continuing to remember

Today there are some who believe that the actual meaning of Memorial Day has been lost and that the holiday has become little more than a day for picnics, barbecues, and trips to the beach. “Of course I am aware of the true meaning of Memorial Day,” says Florida resident Juan Gomez, “but we usually use the long weekend to visit with friends and family. Our activities rarely involve any formal remembrance of the soldiers who have died in battle.”

Senator Daniel Inouye (Hawaii) worries that too many Americans have lost sight of Memorial Day’s significance. He blames the holiday’s subdued celebration on the fact that its observance was moved from May 30 to the last Monday in May in 1971, in compliance with the National Holiday Act requiring all Federal holidays to provide three-day weekends. “Instead of recognizing Memorial Day as a time to honor and reflect on the sacrifices made by Americans in combat, many celebrate the day as the beginning of summer,” explains Sen. Inouye. “We must look on the day as one of remembrance as well as education. The youth of our nation have much to learn from our great patriots. Lessons about duty, honor, and sacrifice will guide them as they become our nation’s future leaders.” In an effort to redirect attention to the holiday’s original meaning, Sen. Inouye has introduced bills—in every session of Congress since 1989—that would restore observance of Memorial Day to May 30.

However, some assert other reasons that Memorial Day celebrations are not as robust as they once were. Says Terrell Upson, who served as a lieutenant in the Navy during the Bay of Pigs conflict: “World War II was a great triumph for the Allied Forces. As Americans, we entered the conflict united, and we all made sacrifices for the good of the cause. When the war finally ended with the total and unconditional surrender of the enemy, we believed that we had achieved something that made the world a better place. But the conflicts that we have been engaged in since have not been as clear cut to most Americans in terms of right and wrong, and have not been as universally supported politically. Although the efforts of our armed forces have been no less valiant, admirable, or appreciated, I believe that national expression of our gratitude has been blunted in some cases by our conflicting points of view.”

Honoring heroes past and present

Whatever the reason, few places celebrate Memorial Day with the vigor that we once expected, but there is reason to believe that enthusiasm for the holiday is again on the rise. The National Memorial Day Parade returned to Washington, D.C., in 2005, after a hiatus more than 60 years. Organized by the American Veteran’s Center, thousands of spectators lined the streets of the nation’s capital for the first national Memorial Day parade since the outbreak of World War II. The parade has been held every year since, and enthusiasm continues to grow—drawing nearly 300,000 spectators since 2007.

“It’s important for all of us to remember that our soldiers are fighting for us right now in Afghanistan and Iraq. Some of them have done as many as five and even six nine-month tours of duty in war zones. During World War II, the average tour was only 45 days,” says Laura Ymker, director of the National Memorial Day Parade for the American Veteran’s Center. According to Ymker, the Washington parade pays tribute to veterans of all American wars. “All branches of the military are represented,” she says, adding that the parade includes costumed re-enactments of Revolutionary and Civil War battles. “All of our soldiers helped to make America what it is today. We honor them all.”

There are other national observances as well. All U.S. flags are still flown at half-staff from dawn until noon on the holiday. Since the late 1950s, the soldiers of the 3rd U.S. Infantry Regiment have placed American flags at each of the 260,000 gravestones at Arlington National Cemetery on the Thursday before Memorial Day, and kept vigil throughout the weekend to ensure that they remain standing. In 2000, a National Moment of Remembrance via silent contemplation, or by listening to taps, was decreed to be observed on Memorial Day at 3 p.m. local time.

Though simple, these observances mean a great deal to America’s servicemen and women stationed overseas. “It’s important for soldiers to know that the people back at home remember them. It reminds them that what they are doing is appreciated,” says Doug Ross-Walsh, a second-year student at West Point Military Academy, who has seen many of his older classmates shipped out over the last two years.

“For those of us old enough to remember, Memorial Day is a national nostalgia for moral commitment,” says Michael Vaccariello of Duluth, Georgia, who served as an Army Corporal during America’s conflict in Korea. Viewed that way, it is likely that enthusiasm for the holiday will never go out of style.

A sign of the times: Today even memorial tributes are high-tech. Some people utilize Web sites like Legacy.com to share stories and photos about their loved ones with family and friends across the world.

Memorial First?

There are many possible first Memorial Days spread across our young nation during the heartache of the Civil War. But one of the most interesting tales of remembering our U.S. heroes took place in Charleston, South Carolina, in 1865—just days before the city’s official surrender to Union forces, asserts David Blight, a professor of American History at Yale University.

According to Blight, roughly 260 captured Union soldiers had died in a makeshift, open-air prison at the city’s Washington Race Course and had been carelessly interred in a mass grave. The city’s black residents, mostly newly freed slaves, worked for two weeks to bury the bodies in individual graves, and then on May 1, they honored the soldiers’ sacrifice with a solemn ceremony.

“On that day in May, 10,000 of the city’s black residents, including five preachers and 2,800 children, entered the race course grounds softly singing ‘John Brown’s Body,’ ” says Blight. “The mourners then conducted a formal ceremony, which included songs and scriptural readings in honor of those soldiers who had helped to achieve their freedom.”

The event, which is the subject of a book by Blight titled Race and Reunion and published by Harvard University Press, was described in the Charleston Daily Courier, the New York Herald Tribune, Harper’s Weekly, and several other publications at the time, but since then has disappeared from mention. “I came across some documents describing the event while doing research at the Harvard University Library,” explains Blight. “That was the first time I had encountered the story, but by checking several newspaper records from that date, I was able to verify the validity of the occurrence.”

On May 31, 2010, the city of Charleston commemorated the gesture of those mourners with a bronze plaque in recognition of the occurrence. “It has been a long time in coming,” says Blight. But finally that memorial observance will become a part of recorded history.