20 Years Later, Stephen King’s On Writing Remains a Career High

It’s frankly impossible to overstate the influence of Stephen King on American popular culture. Sure, we all know that he’s the King of Horror and that he’s sold over 350 million books and that his work is regularly adapted into film and television and comics. His impact and influence hasn’t just been exerted on the field of horror and fantasy, but on so-called “literary” writers like Victor LaValle, Sherman Alexie, Karen Russell, and Haruki Murakami. With more than 60 novels, five non-fiction works, and over 200 short stories to his credit, it might also be impossible to select the quintessential King book. However, if you had to pick the work that says the most about King himself, it’s almost certainly On Writing: A Memoir of the Craft. Part origin story, part how-to manual, and part harrowing depiction of King’s recovery from a near-fatal accident, the widely praised book is celebrating its 20th anniversary with a new edition that includes contributions from his sons, the writers Joe Hill and Owen King. Now, in the week of King’s 73rd birthday, here’s a look at what makes On Writing an Entertainment Weekly New Classic, a Time Top 100 Nonfiction book, and The Cleveland Plain Dealer’s “best book about writing, period.”

Stephen King presents a wide-ranging talk about writing (Uploaded to YouTube by Politics and Prose)

The first major section of the book is called C.V. (the abbreviation for curriculum vitae, which is a look at one’s body of work). In this first of two extensive autobiographical passages, King deals comprehensively with his difficult youth, his discovery of his passion for writing, falling in love with wife (the novelist Tabitha King), breaking through with Carrie, his early fame, and his subsequent battle with alcoholism and substance abuse (which was extensive enough to require an intervention; King notes that he doesn’t remember writing all of Cujo). Each story is a block in the foundation of King’s voice. You gain an understanding of many of the levers that move his prodigious output. King also notes the self-involvement (or even obsession) that writers can fall prey to and relates the story of two desks that he’s used for writing, allowing it to become a metaphor for one simple idea: “Life isn’t a support system for art. It’s the other way around.”

The backbone of what you might call the instructional part of the text is the middle, with section names like “What Writing Is,” “Toolbox,” and “On Writing.” The thing that really separates On Writing from other how-to books about the field is King’s approach. While there’s a degree of “this is how you do it,” King readily admits throughout that, more or less, “this is how I do it,” noting frequently that the specifics of process change for each writer. He’s not giving you step-by-step Ikea instructions; he’s giving you a route while acknowledging that there are still many other routes that will get you to the destination. His tone is one of encouragement, but also one of caution; King believes that talent is an unteachable intangible, but he also believes in craft and improvement. That’s part of what makes the “Toolbox” section critical, in that he emphasizes the tools that all writers should have, particularly vocabulary, grammar, and style.

Stephen King talks about his writing process (Uploaded to YouTube by Bangor Daily News)

The middle portion of the book draws much attention from critics because of its plain-spoken approach. King simultaneously demystifies that process of writing while also attributing some of the success of it to “magic.” But King seems to impart that you don’t get to magic without knowing the tools, and that’s important. Writers need to read, they need time to form, and they need to work. King isn’t King just because of his fame or money or output, it’s because he works. Every day, the Sun comes up, babies are born, and Stephen King is writing something. There’s optimism in his instruction, almost an “if I can do it, you can do it” kind of humbleness, even as he points out that this stuff isn’t as easy as he makes it look. He’s not teaching you how to become a brand name, but he’s teaching you about the discipline.

“On Living: A Postscript” sees King dealing with the accident that nearly killed him in 1999. As he was out for a walk, King was struck by a van driven by a distracted driver. He suffered grave injuries; among them, his leg was broken in nine places, his knee was basically split, his right hip was fractured, he had four broken ribs, and his spine was “chipped in eight places.” As terrible as that sounds (and it was terrible), King somehow landed in the perfect spot after the impact threw him several feet through the air. If he had deviated in course to the left or right, he likely would have suffered fatal traumatic head injury due to rocks or railing. As it was, he was in the hospital for three weeks and went through multiple surgeries to address his injuries. King then confronted something else that was harrowing in its own right: getting back to a writing routine after that, something that Tabitha King played a crucial role in achieving. Obviously, King succeeded, but the difficulty that he had is palpable on the page.

Stephen and Owen King talk about collaborating (Uploaded to YouTube by Good Morning America)

In the anniversary edition, King’s sons offer contributions. Joe Hill has built his own bestselling brand in the horror genre with novels, comics, and short stories, while also seeing film and television adaptations of his work, notably Locke & Key and NOS4A2. Owen King is also a prolific writer of novels, short stories, and articles who in 2017 co-wrote the novel Sleeping Beauties with his father. Hill’s contribution is his transcript of a talk with his father at Porter Square Books from 2019, while Owen King’s piece reprints his article “Recording Audiobooks For My Dad, Stephen King” from the New Yorker site. Both segments add insight to the process that bring some extra color to the book overall. There’s also an updated “Reading List” from King himself, packed with books that he simply thinks that writers should read, which contains items perhaps expected (Golding’s Lord of the Flies, Conrad’s Heart of Darkness) and unexpected (Anne Proulx’s The Shipping News, Evelyn Waugh’s Brideshead Revisited).

As a writer, King’s impact is immeasurable. Heavily awarded over time, King can count a National Book Foundation Medal for Distinguished Contribution to American Letters, a World Fantasy Award for Life Achievement, and a National Medal of Arts among his accolades. On Writing is certainly a departure from expectations, but it remains thoroughly King. It’s considered a high-water mark for a book of its type because articulates big ideas in a way that anyone can understand, and it offers encouragement in a discouraging profession (and world). King insists that all writers need to read; On Writing remains a great place to start.

Featured image: George Koroneos / Shutterstock

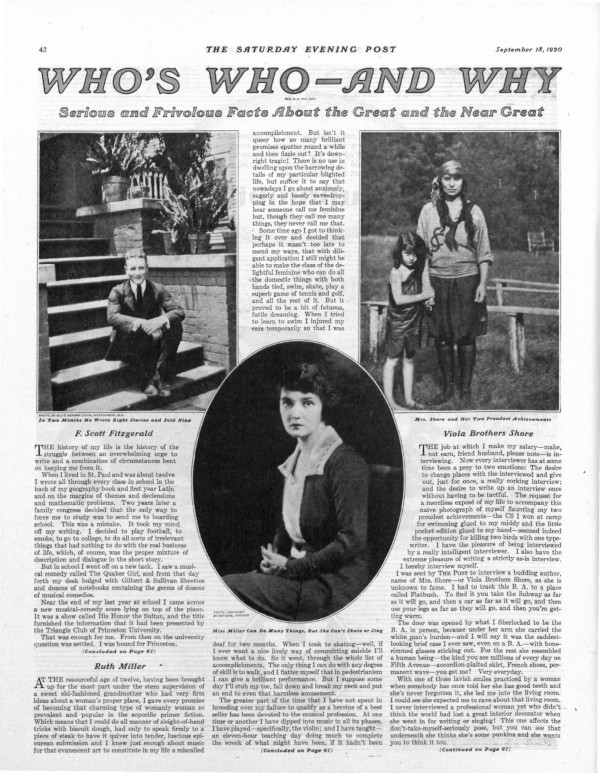

F. Scott Fitzgerald’s Rocky Start in Writing

Amidst the gleam of his emerging career, F. Scott Fitzgerald wrote a short personal essay for the Post’s “Who’s Who — and Why?” section letting the magazine’s readers in on where this new writer had come from. The year, 1920, had been a momentous one for Fitzgerald, having published his first novel, This Side of Paradise, along with several short stories: first, “Head and Shoulders,” and “The Ice Palace,” and later the famous “Bernice Bobs Her Hair.” The “jazz age” author offers distant comments on his life hitherto as though it were all an ironic dream leading him to inevitable success. Fitzgerald would muse about his own life for the magazine many more times in the years to come, penning “How to Live on $36,000 a Year” in 1924 and “One Hundred False Starts” in 1933.

Originally Published on September 18, 1920

The history of my life is the history of the struggle between an overwhelming urge to write and a combination of circumstances bent on keeping me from it.

When I lived in St. Paul and was about twelve I wrote all through every class in school in the back of my geography book and first year Latin and on the margins of themes and declensions and mathematic problems. Two years later a family congress decided that the only way to force me to study was to send me to boarding school. This was a mistake. It took my mind off my writing. I decided to play football, to smoke, to go to college, to do all sorts of irrelevant things that had nothing to do with the real business of life, which, of course, was the proper mixture of description and dialogue in the short story.

But in school I went off on a new tack. I saw a musical comedy called The Quaker Girl, and from that day forth my desk bulged with Gilbert & Sullivan librettos and dozens of notebooks containing the germs of dozens of musical comedies.

Near the end of my last year at school I came across a new musical comedy score lying on top of the piano. It was a show called His Honor the Sultan, and the title furnished the information that it had been presented by the Triangle Club of Princeton University.

That was enough for me. From then on the university question was settled. I was bound for Princeton.

I spent my entire Freshman year writing an operetta for the Triangle Club. To do this I failed in algebra, trigonometry, coordinate geometry, and hygiene. But the Triangle Club accepted my show, and by tutoring all through a stuffy August I managed to come back a Sophomore and act in it as a chorus girl. A little after this came a hiatus. My health broke down and I left college one December to spend the rest of the year recuperating in the West. Almost my final memory before I left was of writing a last lyric on that year’s Triangle production while in bed in the infirmary with a high fever.

The next year, 1916-17, found me back in college, but by this time I had decided that poetry was the only thing worthwhile, so with my head ringing with the meters of Swinburne and the matters of Rupert Brooke I spent the spring doing sonnets, ballads and rondels into the small hours. I had read somewhere that every great poet had written great poetry before he was 21. I had only a year and, besides, war was impending. I must publish a book of startling verse before I was engulfed.

By autumn I was in an infantry officers’ training camp at Fort Leavenworth, with poetry in the discard and a brand new ambition—I was writing an immortal novel. Every evening, concealing my pad behind Small Problems for Infantry, I wrote paragraph after paragraph on a somewhat edited history of me and my imagination. The outline of 22 chapters, four of them in verse, was made, two chapters were completed; and then I was detected and the game was up. I could write no more during study period.

This was a distinct complication. I had only three months to live — in those days all infantry officers thought they had only three months to live — and I had left no mark on the world. But such consuming ambition was not to be thwarted by a mere war. Every Saturday at one o’clock when the week’s work was over I hurried to the Officers’ Club, and there, in a corner of a roomful of smoke, conversation and rattling newspapers, I wrote a one-hundred-and-twenty-thousand-word novel on the consecutive weekends of three months. There was no revising; there was no time for it. As I finished each chapter I sent it to a typist in Princeton.

Meanwhile I lived in its smeary pencil pages. The drills, marches and Small Problems for Infantry were a shadowy dream. My whole heart was concentrated upon my book.

I went to my regiment happy. I had written a novel. The war could now go on. I forgot paragraphs and pentameters, similes and syllogisms. I got to be a first lieutenant, got my orders overseas — and then the publishers wrote me that though The Romantic Egotist was the most original manuscript they had received for years they couldn’t publish it. It was crude and reached no conclusion.

It was six months after this that I arrived in New York and presented my card to the office boys of seven city editors asking to be taken on as a reporter. I had just turned 22, the war was over, and I was going to trail murderers by day and do short stories by night. But the newspapers didn’t need me. They sent their office boys out to tell me they didn’t need me. They decided definitely and irrevocably by the sound of my name on a calling card that I was absolutely unfitted to be a reporter.

Instead I became an advertising man at 90 dollars a month, writing the slogans that while away the weary hours in rural trolley cars. After hours I wrote stories — from March to June. There were 19 altogether; the quickest written in an hour and a half, the slowest in three days. No one bought them, no one sent personal letters. I had 122 rejection slips pinned in a frieze about my room. I wrote movies. I wrote song lyrics. I wrote complicated advertising schemes. I wrote poems. I wrote sketches. I wrote jokes. Near the end of June I sold one story for 30 dollars.

On the Fourth of July, utterly disgusted with myself and all the editors, I went home to St. Paul and informed family and friends that I had given up my position and had come home to write a novel. They nodded politely, changed the subject and spoke of me very gently. But this time I knew what I was doing. I had a novel to write at last, and all through two hot months I wrote and revised and compiled and boiled down. On September 15th This Side of Paradise was accepted by special delivery.

In the next two months I wrote eight stories and sold nine. The ninth was accepted by the same magazine that had rejected it four months before. Then, in November, I sold my first story to the editors of The Saturday Evening Post. By February I had sold them half a dozen. Then my novel came out. Then I got married. Now I spend my time wondering how it all happened.

In the words of the immortal Julius Caesar: “That’s all there is; there isn’t anymore.”

Featured image: The Saturday Evening Post, September 18, 1920

Eugene Field Helped Craft America’s Sense of Humor, Then We Forgot Him

When Eugene Field died in 1895 at age 45, fellow authors and friends hastened to share their fond memories of the humorist and poet. He was a hilarious prankster and a heavy drinker with an impressive book collection, but, most of all, he was a loyal friend.

Field was born 170 years ago on September 2, 1850, although he reportedly told people his birthday was September 3rd if they were late to wish him a happy birthday, just so they wouldn’t feel too bad about it.

Even though more than 30 elementary schools around the country have been named after the prolific writer, his literary renown has scarcely held up to the household-name status he enjoyed during his life. As a poet, he crafted the most popular children’s poems and lullabies of the era, including “Little Boy Blue,” “Wynken, Blynken, and Nod,” and “The Sugar-Plum Tree,” all of which were published in this magazine or its affiliated children’s magazines. As a newspaperman, Field garnered a national following for his witty columns documenting people and the arts, first in Missouri, then in Denver, and finally at the Chicago Daily News.

His column “Sharps and Flats” ran in the latter paper six days a week for the last 12 years of his life. By at least one account, he was the most popular columnist in the country during that time. Of a young Rudyard Kipling, Field wrote that “he has been flattered to an amazing degree since he woke up one morning and found himself famous” and that “there may be … twenty newspaper reporters in New York City capable of doing as good work as Mr. Kipling has done; at the same time, they have not done it and Mr. Kipling has.” Field gushed over a World’s Fair exhibit on Hans Christian Andersen, writing of “that dear heart which beat in unison with the simplicity, the truth, the candor, the enthusiasm, the wisdom, and the pathos of childhood!”

Field was also known for his scathing and sardonic quips on politicians of the day. In 1883, he wrote, “Grover Cleveland seems to have suddenly and completely dropped out of sight. Perhaps he is rehearsing Santa Claus for a Sunday-school celebration next Christmas. These politicians are queer people.” Writing for the Denver Tribune, he offered whimsical advice for all children aspiring to go into politics: “If you neglect your education and learn to chew plug tobacco, maybe you will be a statesman some time. Some statesmen go to Congress and some go to jail. But it is the same thing, after all.” One can imagine that Field would have found no shortage of bon mots to pen on the Progressive Era of American politics, had he lived to see it.

A few years after his death, Francis Wilson memorialized the writer in a biography published in this magazine as “The Eugene Field I Knew,” writing, “Field’s mind and heart were wide open to the sunshine of humor and the joy of laughter.” Sometimes this candidness expressed itself in wild antics, as when Field reportedly pranked a posh Thanksgiving dinner party by exploding the turkey with a firecracker: “He wasn’t invited back.”

Field’s close friend George H. Yenowine wrote for the Post several years later on “The Serious Side of Eugene Field,” claiming he had received the former’s last written letter. Yenowine noted that Field wrote his correspondence in six different colors of ink, depending on the tone of a given letter. He was also known to spend hours embellishing the margins with drawings and designs. In his letter to Yenowine two days before his death, Field went on excitedly about many projects he was looking forward to, before finishing the missive with a characteristic confession: “Irving Way has been wanting me to do the preface to the volume of Anne Bradstreet’s poems which the Duodecimo will publish; but Anne is a tough, uncongenial old bird, and I hesitate to tackle her. I suppose that one is justified in putting off a task he feels he cannot do well.”

Although Field’s prominence in the American literary canon has waned, his influential effect on humorists into the 20th century, such as John T. McCutcheon, Mark Twain, and even — tangentially — Molly Ivins, is undeniable. Don Marquis professed that he read “Sharps and Flats” every day. In his 2001 biography, Eugene Field and His Age, author Lewis O. Saum claims that Field created the newspaper column, and yet much of the writer’s work from the Chicago Daily News was lost forever: “We knew him very well for something like a half-century. Then, recalling little other than something labeled ‘calamitously sentimental,’ we averted our gaze.”

Field’s irreverent approach to constructing the record of the day can be remembered as a quaint, but formative, addition to the uniquely American voice; the oversized role he played in holding a mirror to the country and its politics at such a precarious time as the late 19th century has received a fraction of the attention it deserves.

Featured image: Buffalo Evening News, December 3, 1895

Six Things You Didn’t Know About To Kill a Mockingbird

Harper Lee’s classic novel To Kill a Mockingbird went on sale 60 years ago this week. The two-part structure of the novel deals with the Alabama childhood of Jean Louise “Scout” Finch and the challenging case taken on by her lawyer father, Atticus. It’s one of the most widely-read books in the United States and a staple of middle and high school curricula. In honor of the six decades that the Pulitzer Prize-winning novel has been a cultural touchstone, here are six things you didn’t know about To Kill a Mockingbird, its writer, and the award-winning film.

1. The First Draft Is an Entirely Different Book

Lee lived in New York City in the 1950s, working in reservations for British Overseas Airways. Her childhood friend, the writer Truman Capote (more on him later), connected her with an agent in 1956. Lee’s friends supported her for a year so that she could write her book; the novel, Go Set a Watchman, sold to the publisher J. B. Lippincott Company. Editor Tay Hohoff felt the book had promise but also that it needed more work. For over two –and –a half years, she worked with Lee to transform Watchman into the book that would be To Kill a Mockingbird. In a twist that could only happen for a book as famous as Mockingbird, that first draft, Go Set a Watchman, was released as its own book in 2015. HarperCollins, who published Watchman, faced harsh criticism from several quarters for marketing that positioned the book like a sequel rather than a first draft; they drew additional fire for the perception that Lee had been manipulated into allowing the release just a few weeks after the death of her primary caregiver, her sister Alice.

2. Harper Lee, Truman Capote, and Kansas

Truman Capote wasn’t just Lee’s childhood friend; he was the inspiration for the character Dill in Mockingbird. In 1959, as Lee waited for the publication of the novel the following year, she went with Capote to Kansas on a research trip. Capote was pursuing an article on the murder of a farming family, the Clutters. The article eventually grew into Capote’s seminal work, the 1966 book In Cold Blood. Over the years, that trip has taken on an almost mythic status in the literary world. It’s been depicted in two films: Infamous, based on George Plimpton’s book Truman Capote: In Which Various Friends, Enemies, Acquaintances, and Detractors Recall His Turbulent Career and starring Toby Jones as Capote and Sandra Bullock as Lee; and Capote, based on Gerald Clarke’s biography of the same name and starring Phillip Seymour Hoffman and Catherine Keener. The trip was also depicted in the acclaimed graphic novel Capote in Kansas by writer Ande Parks and artist Chris Samnee.

3. Lee Received Presidential Material

Harper Lee Receives the Presidential Medal of Freedom. (Uploaded to YouTube by C-SPAN)

It’s not unusual for writers to be awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom or the National Medal of Arts. It’s very unusual to receive both on the strength of one book. For 55 years, Lee had only one novel published (and some argue the validity of Watchman as a novel at all, given its odd draft status). However, it’s a tribute to the impact of the book that Lee received the Medal of Freedom from George W. Bush in 2007 and the Medal of Arts from Barrack Obama in 2010.

4. The Novel Continues to Face Challenges

Despite the novel’s iconic status, it remains one of the most challenged by various groups that want it removed from school curricula or public libraries. It was the seventh most-challenged book as recently as 2017, according to the American Library Association. As early as 1966, the book received challenges on the basis of content related to rape. Despite the anti-racism messaging prevalent in the book, it’s been challenged for containing racial epithets. Mockingbird also draws fire for its inclusion of profanity not related to race.

5. Atticus Finch Set a High Bar

The trailer for To Kill a Mockingbird. (Uploaded to YouTube by Movieclips Classic Trailers)

Atticus Finch has been praised as a both a literary hero and, as portrayed by Gregory Peck, a hero of film as well. Peck won an Academy Award for his work in the 1962 film. The American Film Institute’s 2003 list, “100 Heroes & Villains” named Finch as the greatest hero in American movies. In 1993, DC Comics writer and artist Dan Jurgens used a scene in Superman #81 to cement the notion that the adaptation of the novel is Clark Kent’s (and therefore Superman’s) favorite movie. Over time, some writers have questioned the lionization of Finch, mainly noting that he takes on a racist in the courtroom, but does little to take on the racism endemic in their hometown.

6. The Mystery of Boo Radley

The mysterious nature of Boo Radley in the novel and film has made him something of a cult character and a shorthand reference for an unseen figure in a narrative. The role of Radley marked the film debut of celebrated actor Robert Duvall, who has since been nominated for seven Academy Awards (winning one for Best Actor in Tender Mercies). British band The Boo Radleys took their name from the Finch’s neighbor. And Bruce Hornsby’s song “Sneaking Up on Boo Radley” is about the events of the novel related to the character.

Featured image: Shutterstock

Inside the Archive: Perry Mason in the Post

Saturday Evening Post members can read these and other stories from our complete archives. Subscribe today.

For decades, the Post was considered the pinnacle of the magazine-fiction market. Authors knew if their story or serialized novel appeared in the magazine, they’d reached the big point in their career.

The Post had introduced G.K. Chesterton’s Father Brown to America, as well as Agatha Christie’s Hercules Poirot. And in 1937, the Post brought millions of readers Perry Mason in Erle Stanley Gardner’s The Case of the Lame Canary.

Mason wasn’t a complete unknown. He’d first appeared in The Case of the Velvet Claws with the words, “Perry Mason sat at the big desk. There was about him the attitude of one who is waiting. His face in repose was the like the face of a chess player who is studying the board. That face seldom changed expression. Only the eyes changed expression.”

The Mason of this early work showed the pulp-fiction roots of his author, Erle Stanley Gardner. He has none of the smoothly polished manner of his TV persona. The character is a little rough around the edges, but so is the writing. At this point in his career — 1933 — Gardner was a long way from becoming the country’s most popular mystery narrator.

But the story has many redeeming qualities, particularly Mason’s ability to see motive behind lies, which enabled Gardner to sell his next Mason novel: The Case of the Sulky Girl.

By his tenth Perry Mason novel, Gardner’s work met with the approval from the Post’s fiction editors. And so The Case of the Lame Canary was serialized across eight issues beginning May 29, 1937.

Mason returned in 1942 in The Case of the Careless Kitten, which ran in the Post May 23̶July 11, 1952, a mystery that featured, according to one critic, “a well constructed mystery plot with an ingenious solution.”

The Post can’t take credit for establishing Gardner’s reputation, but we did help get Perry Mason ready for television. According to one source, Gardner dropped some of Mason’s pulp-fiction characteristics for the Post readership. He also added more love interest and made Mason less willing to bend the law to help clients.

Gardner’s Mason novels appeared frequently through the 1950s and early 1960s. Overall, the Post serialized 16 of his cases.

Perry Mason in the Post

Saturday Evening Post members can read these and other stories from our complete archives. Subscribe today.

- The Case of the Lame Canary

- May 29, Jun 5, Jun 12, Jun 19, Jun 26, Jul 3, Jul 10, Jul 17 1937

- The Case of the Careless Kitten

- May 23, May 30, Jun 6, Jun 13, Jun 20, Jun 27, Jul 4, Jul 11 1942; The Mystery Deepens.

- The Case of the Fugitive Nurse

- Sep 19, Sep 26, Oct 3, Oct 10, Oct 17, Oct 24, Oct 31, Nov 7 1953

- The Case of the Restless Redhead

- Sep 11, Sep 18, Sep 25, Oct 2, Oct 9, Oct 16, Oct 23, Oct 30 1954

- The Case of the Sun Bather’s Diary

- Mar 12, Mar 19, Mar 26, Apr 2, Apr 9, Apr 16, Apr 23 1955

- The Case of the Missing Poison

- Dec 10, Dec 17, Dec 24, Dec 31 1955, Jan 7, Jan 14, Jan 21, Jan 28 1956

- The Case of the Lucky Loser

- Sep 1, Sep 8, Sep 15, Sep 22, Sep 29, Oct 6, Oct 13, Oct 20 1956

- The Case of the Dead Man’s Daughter

- Aug 10, Aug 17, Aug 24, Aug 31, Sep 7, Sep 14, Sep 21, Sep 28 1957

- The Case of the Footloose Doll

- Feb 1, Feb 8, Feb 15, Feb 22, Mar 1, Mar 8, Mar 15, Mar 22 1958

- The Case of the Greedy Grandpa

- Oct 25, Nov 1, Nov 8, Nov 15, Nov 22, Nov 29, Dec 6, Dec 13 1958

- The Case of the Mythical Monkeys

- May 2, May 9, May 16, May 23, May 30, Jun 6, Jun 13, Jun 20 1959

- The Case of the Waylaid Wolf

- Sep 5, Sep 12, Sep 19, Sep 26, Oct 3, Oct 10, Oct 17, Oct 24 1959

- The Case of the Duplicate Daughter

- Jun 4, Jun 11, Jun 18, Jun 25, Jul 2, Jul 9, Jul 16, Jul 23 1960

- The Case of the Spurious Spinster

- Jan 28, Feb 18, Feb 25, Mar 11, 1961

- The Case of the Bigamous Spouse

- Jul 15, Jul 22, Jul 29, Aug 5, Aug 12, Aug 19, Aug 26 1961

- The Case of the Mischievous Doll

- Dec 8 1962

Just as Gardner reshaped Perry Mason for the Post readership, the Post re-imaged Mason to reflect his more familiar incarnation: TV’s Raymond Burr. The Post’s story illustrations show a strong TV influence.

- July 15, 1961, page 17

- June 4, 1960 page 23

- Sep 12, 1959 page 34

- Sep 26, 1959 page 36

- Oct 25, 1958 page 27

Perry Mason was far from Gardner’s only character. He wrote stories with a number of protagonists. One the less famous is Peter Quint, who stars in three stories about a salesman who is fast witted and imaginative (though he’s no Alexander Botts). All three Quint stories appeared in the Post.

Peter Quint in the Post

- “The Last Bell on the Street”

- May 3 1941

- “That’s a Woman for You”

- May 31 1941

- “The Big Squeeze”

- Nov 15 1941

Gardner also offered the view from the prosecution table with a character named Doug Selby. He’s a District Attorney elected on a reform platform. He solves mysteries in a rural California county while fighting political corruption. His nemesis is a ruthless, crooked defense attorney. Two Selby stories ran in the Post.

Doug Selby in the Post

- “The D.A. Breaks a Seal”

- Dec 1, Dec 8, Dec 15, Dec 22, Dec 29 1945, Jan 5, Jan 12 1946

- “The D.A. Takes a Chance”

- Jul 31, Aug 7, Aug 14, Aug 21, Aug 28, Sep 4, Sep 11, Sep 18 1948

Featured image: Illustration by James R. Bingham for “The Case of the Greedy Grandpa” by Earle Stanley Gardner, from the October 25, 1958, issue of the Post (© SEPS).

Guide to the Archive: An Intrepid Journalist Covers World War II for the Post

Journalist Richard Tregaskis had been covering World War II since its earliest days. He witnessed the Battle of Midway and he was with the Marines during the first months of fighting on Guadalcanal Island. He also wrote dispatches for The Saturday Evening Post, writing about the dangers that G.I.s faced in Europe and the Pacific Theater.

Saturday Evening Post members can enjoy reading Tregaskis’s articles in our digital archive, along with stories by other greats such as Ray Bradbury, Dorothy Parker, and Jack London.

Articles by Richard Tregaskis

All articles can be found in our digital archives.

“House to House and Room to Room,” February 24, 1945, page 18

“Road to Tokyo—We of the B-29’s Say Good-By,” August 18, 1945, page 17

“Road to Tokyo—‘I Don’t Intend to Ditch’,” August 25, 1945, page 20

“Road to Tokyo—Disillusionment in Hawaii,” September 1, 1945, page 20

“Road to Tokyo—‘Guam—This is It!’,” September 8, 1945, page 22

“Road to Tokyo—‘Fighters Right Close . . . at 7 o’Clock’,” September 15, 1945, page 20

“Road to Tokyo—Pay-Off Over Japan,” September 22, 1945, page 20

“Road to Tokyo—Peace Caught Us Napping,” September 29, 1945, page 20

“Road to Tokyo—We Soften the Peace,” October 6, 1945, page 20

“Road to Tokyo—The Infantry Never Had it So Tough,” October 13, 1945, page 20

“Road to Tokyo—The Fine Hand of Mr. Suzuki,” October 20, 1945, page 18

“Road to Tokyo—Have We Given Japan Back to the Japs?” October 27, 1945, page 20

“Pappy Hain Comes Home,” January 19, 1946, page 20

“Jim Davis Comes Home,” February 9, 1946, page 17

“Commando Kelly, Businessman,” March 2, 1946, page 22

“A Hot Pilot Cools Off,” March 23, 1946, page 17

“Brash Young Man,” April 13, 1946, page 18

“The Bombardier Who Would Build Cities,” May 4, 1946, page 21

“The Marine Corps Fights for Its Life,” February 5, 1949, page 20

“The Cities of America: Norfolk,” July 9, 1949, page 42

“Gabreski, Avenger of the Skies,” December 13, 1952, page 17

“The Cops’ Favorite Make-Believe Cop,” September 26, 1953, page 24

Featured image: The 160th Infantry on the beach at Guadalcanal (Department of the Army)

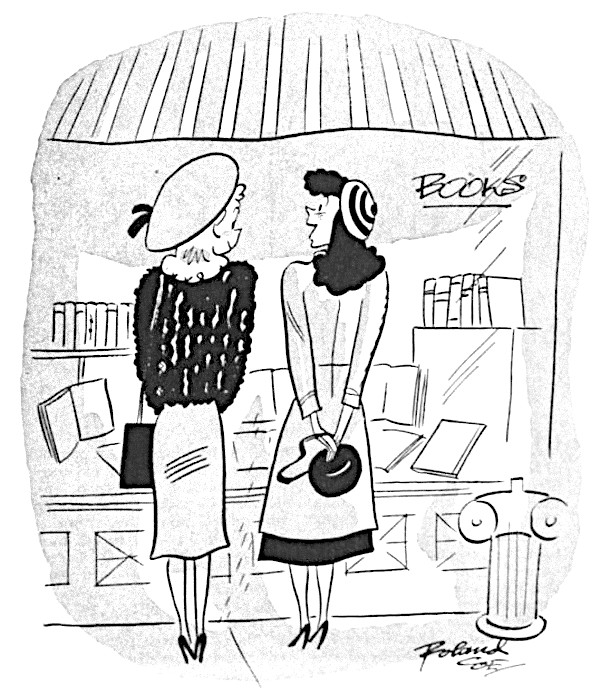

Cartoons: Author! Author!

Want even more laughs? Subscribe to the magazine for cartoons, art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

January 24, 1953

Roland Coe

November 29, 1952

Locke

September 13, 1952

Doris Matthews

April 28, 1951

Goldstein

February 7, 1953

Want even more laughs? Subscribe to the magazine for cartoons, art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Guide to the Archive: Agatha Christie

In the 1930s and ’40s, Agatha Christie’s work appeared frequently in The Saturday Evening Post.

Way back in 1933, the Post introduced her Belgian detective, Hercules Poirot, to America. Altogether Christie’s cerebral sleuth appeared in six Post issues during the 1930s. The Post also published six other mysteries by Christie, including “Endless Night,” a lesser known work that she included among her five favorite books.

Stories by Agatha Christie

“Murder in the Calais Coach, Part 1,” September 30, 1933, page 5

“Murder in the Calais Coach, Part 2,” October 7, 1933, page 20

“Murder in the Calais Coach, Part 3,” October 14, 1933, page 18

“Murder in the Calais Coach, Part 4,” October 21, 1933, page 20

“Murder in the Calais Coach, Part 5,” October 28, 1933, page 26

“Murder in the Calais Coach, Part 6,” November 4, 1933, page 26

“Murder in Three Acts, Part 1,” June 9, 1934, page 5

“Murder in Three Acts, Part 2,” June 16, 1934, page 20

“Murder in Three Acts, Part 3,” June 23, 1934, page 20

“Murder in Three Acts, Part 4,” June 30, 1934, page 20

“Murder in Three Acts, Part 5,” July 7, 1934, page 20

“Murder in Three Acts, Part 6,” July 14, 1934, page 26

“Death in the Air,” Part 1,” February 9, 1935, page 5

“Death in the Air,” Part 2,” February 16, 1935, page 20

“Death in the Air,” Part 3,” February 23, 1935, page 20

“Death in the Air,” Part 4,” March 2, 1935, page 26

“Death in the Air,” Part 5,” March 9, 1935, page 26

“Death in the Air,” Part 6,” March 16, 1935, page 24

“Murder in Mesopotamia, Part 1,” November 9, 1935, page 5

“Murder in Mesopotamia, Part 2,” November 16, 1935, page 20

“Murder in Mesopotamia, Part 3,” November 23, 1935, page 20

“Murder in Mesopotamia, Part 4,” November 30, 1935, page 20

“Murder in Mesopotamia, Part 5,” December 7, 1935, page 28

“Murder in Mesopotamia, Part 6,” December 14, 1935, page 28

“Cards on the Table, Part 1,” May 2, 1936, page 5

“Cards on the Table, Part 2,” May 9, 1936, page 22

“Cards on the Table, Part 3,” May 16, 1936, page 24

“Cards on the Table, Part 4,” May 23, 1936, page 24

“Cards on the Table, Part 5,” May 30, 1936, page 26

“Cards on the Table, Part 6,” June 6, 1936, page 28

“Poirot Loses a Client, Part 1,” November 7, 1936, page 5

“Poirot Loses a Client, Part 2,” November 14, 1936, page 24

“Poirot Loses a Client, Part 3,” November 21, 1936, page 24

“Poirot Loses a Client, Part 4,” November 28, 1936, page 20

“Poirot Loses a Client, Part 5,” December 5, 1936, page 20

“Poirot Loses a Client, Part 6,” December 12, 1936, page 20

“Poirot Loses a Client, Part 7,” December 19, 1936, page 31

“Death on the Nile, Part 1,” May 15, 1937, page 5

“Death on the Nile, Part 2,” May 22, 1937, page 22

“Death on the Nile, Part 3,” May 29, 1937, page 22

“Death on the Nile, Part 4,” June 5, 1937, page 28

“Death on the Nile, Part 5,” June 12, 1937, page 26

“Death on the Nile, Part 6,” June 19, 1937, page 26

“Death on the Nile, Part 7,” June 26, 1937, page 27

“Death on the Nile, Part 8,” July 3, 1937, page 27

“The Dream,” October 23, 1937, page 8

“Easy to Kill, Part 1,” November 19, 1938, page 5

“Easy to Kill, Part 2,” November 26, 1938, page 20

“Easy to Kill, Part 3,” December 3, 1938, page 20

“Easy to Kill, Part 4,” December 10, 1938, page 27

“Easy to Kill, Part 5,” December 17, 1938, page 26

“Easy to Kill, Part 6,” December 24, 1938, page 20

“Easy to Kill, Part 7,” December 31, 1938, page 38

“—And Then There Were None, Part 1,” May 20, 1939, page 5

“—And Then There Were None, Part 2,” May 27, 1939, page 18

“—And Then There Were None, Part 3,” June 3, 1939, page 27

“—And Then There Were None, Part 4,” June 10, 1939, page 29

“—And Then There Were None, Part 5,” June 17, 1939, page 27

“—And Then There Were None, Part 6,” June 24, 1939, page 26

“—And Then There Were None, Part 7,” July 1, 1939, page 26

“The Body in the Library, Part 1,” May 10, 1941, page 9

“The Body in the Library, Part 2,” May 17, 1941, page 22

“The Body in the Library, Part 3,” May 24, 1941, page 26

“The Body in the Library, Part 4,” May 31, 1941, page 24

“The Body in the Library, Part 5,” June 7, 1941, page 26

“The Body in the Library, Part 6,” June 14, 1941, page 30

“The Body in the Library, Part 7,” June 21, 1941, page 30

“Remembered Death, Part 1,” July 15, 1944, page 9

“Remembered Death, Part 2,” July 22, 1944, page 28

“Remembered Death, Part 3,” July 29, 1944, page 28

“Remembered Death, Part 4,” August 3, 1944, page 32

“Remembered Death, Part 5,” August 12, 1944, page 32

“Remembered Death, Part 6,” August 19, 1944, page 32

“Remembered Death, Part 7,” August 26, 1944, page 32

“Remembered Death, Part 8,” September 2, 1944, page 32

“Endless Night, Part 1” February 24, 1968, page 59

“Endless Night, Part 2,” March 9, 1968, page 50

Video Image Credits

:07 Agatha Christie (National Archives, The Netherlands, CC0)

:17 Albert Finney Hercule Poirot: Alamy

:27 Murder on the Orient Express Promotional Photo: Alamy

:31 Lindbergh Kidnapping Poster (Wikimedia Commons. Published in the United States between 1924 and 1977 without a copyright notice.)

:55 David Suchet Hercule Poirot: Alamy

:59 Kenneth Branagh Hercule Poirot: Alamy

1:18 Endless Night Movie Photograph: Alamy

1:22 Endless Night Movie Photograph Funeral: Alamy

1:43 Ray Bradbury Photo (Wikimedia Commons. Published in the United States between 1924 and 1977 inclusive, without copyright notice.)

1:45 F. Scott Fitzgerald Photo (Wikimedia Commons. Publication occurred prior to January 1, 1924)

1:46 Dorothy Parker Photo (Wikimedia Commons. This image is available from the United States Library of Congress‘s Prints and Photographs division under the digital ID ggbain.05631)

Featured image: Illustration by Rubin, ©SEPS

25 Years Ago: How Stephen King Changed the Universe

Is Stephen King having a moment? Just this month, the second half of the film adaptation of his classic horror novel, It (titled It: Chapter Two), pulled in more than $150 million in America alone in its first nine days. Last week, his 61st novel, The Institute, hit stores. The movie version of his sequel to The Shining, Doctor Sleep, arrives in November. And streaming services positively hum with ongoing and upcoming adaptations of his work, including a new version of The Stand. It may seem like “a moment,” but the truth is that he’s been having an ongoing collection of moments since he became a pop culture force 45 years ago with the release of Carrie. Twenty-five years ago, King was in the middle of another pivotal September, one that would see the release of both a classic film and a novel that fundamentally changed the universe for King’s “constant readers.”

In 1982, King published Different Seasons, a collection of four novellas: The Breathing Method, The Body, Apt Pupil, and Rita Hayworth and Shawshank Redemption. The stories were distinguished from his novels at the time by mostly falling outside of the horror genre. Owing in part to King’s popularity, Hollywood came knocking for the non-horror material, too. The Body was adapted as Stand by Me in 1985, and Apt Pupil, after an abortive attempt ran out of money in 1987, saw screens in 1998.

The film adaptation of Rita Hayworth and Shawshank Redemption eventually came to life through a writer and director who King had previously allowed to film one of his short stories. Frank Darabont had been one of King’s first “Dollar Babies.” That was the nickname given to beneficiaries of King’s policy of allowing students or otherwise aspiring filmmakers to license one of his short stories for one dollar.

Darabont cast Tim Robbins and Morgan Freeman in the leads for the period prison drama. Despite King’s best-selling writer status and proven track record in generating box office dollars, the studio decided to keep King’s name out of the marketing due to his association with horror. In various interviews, King himself has remarked on this disconnect, including a frequently memed conversation he had with an older lady in a supermarket who, when he pointed out that he’d written Shawshank, retorted, “No, you didn’t.” Upon its September 1994 release, the film had a slow start; Forrest Gump was in the middle of its dominating 42-week box office run, and Shawshank went into wide release on the day that Pulp Fiction opened. Squished between two pop culture phenomena and the ongoing runs of The Lion King and lingering action films like Speed and True Lies, the film stiffed.

In a King-like twist, Shawshank came back from the dead due to the necromancy of home video. Warner Home Video shipped more than 300,000 rental copies of the film to outlets like Blockbuster, sensing that the movie might get a second life. They guessed right, and it went on to do huge rental business and was subsequently nominated for seven Academy Awards, including Best Adapted Screenplay (for Darabont), Best Actor (for Freeman), and Best Picture. While it didn’t win, the nominations cemented the image of the film in the public eye as a quality work. It’s thrived on video and television airings ever since. For the past 11 years, it has been #1 on IMDB.com’s user-created list of Top Films. It has also been preserved in the National Film Registry by the Library of Congress.

Within a few days of the initial limited September release of The Shawshank Redemption, King put out a new novel called Insomnia. The book came two years after his 1992 one-two punch of Gerald’s Game and Dolores Claiborne, a pair of novels about women endangered by abusive men and linked by an eclipse. This time, the protagonist, Ralph Roberts, was an elderly widower dealing with his increasing inability to sleep. As the plot runs further and further into a supernatural direction, King pulls out his big surprise roughly three-quarters of the way through: Roberts’s real mission is to save the life of young boy whose existence is critical to the success of another mission, that of The Gunslinger, Roland Deschain, protagonist of King’s The Dark Tower series.

This bombshell revelation did something that King had never done before. Whereas readers understood that the “Castle Rock” books (like Cujo, The Dead Zone, and Needful Things) were connected, and that It and Insomnia both took place in Derry, for example, here was the author planting a flag that the entire span of his stories were connected in one overarching narrative. That meant that seemingly disconnected threads like The Dark Tower and Insomnia were not only connected, but could impact one another. King would make this even more explicit in the fourth Dark Tower book, Wizard and Glass, in 1997, when the main characters crossed over into the world of The Stand. King’s own notes in the book stated that, “I am coming to understand that Roland’s world actually contains all the others of my making.”

The implication from that point forward was that whenever you read a King book, you weren’t just reading a story in isolation; you were reading something that could also been seen as part of a vast tapestry of interconnected worlds, stories, and ideas. The author’s multiverse has been tracked in two editions of The Stephen King Universe, a book compiled by writers Stanley Wiater, Christopher Golden, and Hank Wagner. And though The Dark Tower has ended (we think), King isn’t slowing down with the connections; after Holly Gibney, a protagonist of King’s Bill Hodges Trilogy, popped up in 2018’s The Outsider, King has since promised that she’s the lead character in next year’s If It Bleeds.

Decades after his commercial breakthrough, King never seems to stop having “moments.” He’s earned Grandmaster status from both the Mystery Writers of America and the World Horror Convention. In 2003, he received the National Book Award Medal of Distinguished Contribution to American Letters; in 2014, he was also awarded a National Medal of Arts from the National Endowment of the Arts. His short stories, novels, and the various adaptations of his work continue to be wildly popular. If such moments are themselves stories, then it’s easy to understand in this way: everyone has stories; it’s just that Stephen King is more prolific than the rest of us.

Featured image: Atlaspix / Alamy Stock Photo.