America’s Evolving Opinions of Ayn Rand

Seventy-five years after the publication of The Fountainhead, Ayn Rand’s books continue to sell, and many of her ideas have now changed the way America pays its taxes.

For years, many journalists and academics dismissed her as a crank, and most critics judged her books as tedious and shallow. But many readers disagreed, and The Fountainhead and her next novel, Atlas Shrugged, became huge bestsellers that never went out of print. In 1991, Atlas Shrugged was named as the second most influential book among respondents in a Book of the Month Club survey, just below the Bible. Today, hundreds of thousands of her books are bought each year.

Although Rand considered herself primarily a philosopher, it was the sweeping plots and characters of her novels that inspired many readers to follow her “philosophy” of objectivism, which celebrates individualism and rejects big government. As Rand herself put it, objectivism is “the concept of man as a heroic being, with his own happiness as the moral purpose of his life, with productive achievement as his noblest activity, and reason as his only absolute.” One of her early followers was Alan Greenspan, who became the powerful chairman of the federal reserve bank in many administrations. Her ideas influenced many other right-wing leaders in the Republican party, including Speaker of the House Paul Ryan, as well as many of the GOP Tea Party congressmen. A founder of the Libertarian party has said his group wouldn’t have existed without her.

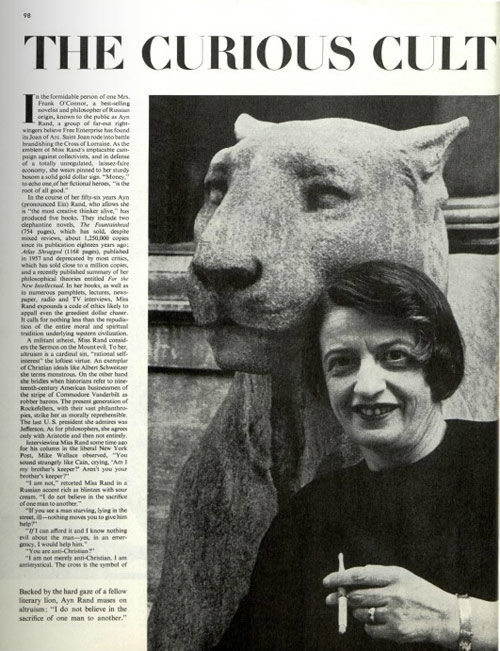

Back in 1961, though, the author of The Saturday Evening Post article “The Curious Cult of Ayn Rand” was scathingly critical of her. Writer John Kobler was put off by her rejection of altruism and her pursuit of self-interest. He mocked her egotism (she claimed she was “the most creative thinker alive”), and Kobler observed that she was intent on “nothing less than the repudiation of the entire moral and spiritual tradition underlying western civilizations.” Kobler called out the paranoia in her “with-us-or-against-us” attitude and her belief that critics were possibly “part of a Communist conspiracy to discredit the movement,” prompting him to refer to Rand and her followers as a cult.

Many Post readers would have likely agreed with Kobler in 1961. Having lived through the Great Depression, Americans had suffered because of others’ reckless stock-market investing. Many others had made significant personal sacrifices during World War II, supporting America’s efforts to destroy tyranny, liberate the oppressed, and rebuild a war-ravaged Europe.

Yet Rand was declaring selfishness a virtue. “Man should neither sacrifice himself to others, nor others to himself.”

But today, despite her atheist, pro-choice views, Rand’s philosophy is still powerfully attractive to some of the most influential conservative politicians — and last year’s tax reform bill, which overhauled the way Americans pay taxes, reflects much of that philosophy of laissez-faire capitalism and individualism. Ayn Rand wasn’t noted for her sense of humor — she sported jewelry in the shape of the dollar sign, her favorite symbol. But 75 years after The Fountainhead, and despite being dismissed by so many influential publications, including The Saturday Evening Post, she is probably having the last laugh.

Featured image: Ayn Rand, from the November 11, 1961, issue of The Saturday Evening Post.