The OTHER Classic Halloween Movies

It’s hard to make a more iconic Halloween movie than Halloween, but that’s not to say that there aren’t legions of other films where Halloween plays a critical role. Much like Christmas, Halloween is such a big holiday in the American imagination that it appears in a number of films that aren’t directly about Halloween, or even horror. Last year, the Post took a look at “The OTHER Classic Christmas Movies,” so it’s only fair that we do the same for Halloween.

10. Batman Forever (1995)

Batman Forever on YouTube Movies

For some reason, the first three modern Batman films all rotated around some kind of holiday celebration. 1989’s Batman featured the Gotham City bicentennial, 1992’s Batman Returns took place at Christmas, and 1995’s Batman Forever landed on Halloween. The holiday doesn’t have a huge impact on the overall plot, but it shows up significantly later in the film. Two-Face (Tommy Lee Jones) and The Riddler (Jim Carrey), having discovered Batman’s secret identity and fool an unusually dim Alfred (Michael Gough) using Halloween costumes. With Alfred’s guard down, the villains and their henchmen invade Wayne Manor, destroying much of the mansion and Batcave while kidnapping Chase Meridian (Nicole Kidman) and setting up a final showdown between the villains, Batman (Val Kilmer), and his new partner, Robin (Chris O’Donnell).

9. Meet Me in St. Louis (1944)

Esther discovers the truth about the street car prank (Uploaded to YouTube by WarnerArchive)

EVERYBODY knows that Meet Me in St. Louis is where we got “Have Yourself a Merry Little Christmas.” But not everyone quite recalls that the movie basically takes place over most of a year from 1903 until the World’s Fair opens in 1904. The movie is based on a novel of the same name by Sally Benson, which was originally presented as a string of short stories in The New Yorker. The Halloween sequence represents a pivotal moment in the plot’s central relationship. Esther (Judy Garland) has been in love with John (Tom Drake) from a distance for a while. However, her sister Tootie alleges that John hurt her while Tootie was out for trick-or-treat. Esther attacks John in a rage, but Tootie admits that John actually protected her and sister Agnes from the police after a bungled prank. Esther’s apology to John leads to their first kiss.

8. Mean Girls (2004)

Halloween from Mean Girls (Uploaded to YouTube by The Paramount Vault)

Tina Fey took on a terrifying subject when she adapted Mean Girls from Rosalind Wiseman’s book, Queen Bees and Wannabees, and that was the teenage trauma associated with high school cliques. Mean Girls covers a lot of ground when it comes to how young women interact, including social expectations versus reality, the spitefulness that can arise in a compressed setting like a high school, and how kids are often unaware of the damage that words can do. One key scene takes place at a Halloween party; the lead-in starts off light, playing off of the ongoing trend of hyper-sexualized costumes, but it takes a turn when Cady (Lindsay Lohan) is betrayed at the party, setting her on a course that affects the rest of the film.

7. We Need to Talk About Kevin (2011)

The trailer for We Need to Talk About Kevin (Uploaded to Movieclips Trailers)

A soul-crushing novel made into a soul-crushing movie, We Need to Talk About Kevin deals with one of the worst possible nightmares for a parent: what do you do when your child is the one who conducts a school massacre? The epistolary novel by Lionel Shriver was made into a haunting film starring Tilda Swinton as Kevin’s mother, Eva. As Eva drives home one night, the demons plaguing her and her family seem to come to life, moving in and out of the shadows as she sees them out her car window. It is, however, only Halloween, but the frightening vista underscores Eva’s own inner turmoil and the tragedy that has played out over the course of Kevin’s life.

6. The Harry Potter Series (2001-2011)

The Mountain Troll scene (Uploaded to YouTube by Movieclips)

Take a hugely successful book series. Recruit appealing newcomers for the young leads. Add some of the most accomplished adult actors in England. Never stray too far from the books. Spend ten years becoming of the one best loved movie series of all time. We all watched that work for the Harry Potter series. Obviously, the magic-based series lends itself to Halloween. Moreover, since every book roughly covers one school year, it’s easy to slot those scenes in the plot. Each book at least references Halloween. Not all of the films touch on it, although there are recurring references. A running concern is the fact that Voldemort was originally defeated on Halloween Night. Rowling also tied important events to the holiday in the first four books. Easily one of the most memorable Halloween scenes is in the first book and first film, Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone. When a Mountain Troll gets into the school, the student body panics. Only Harry and Ron keep their cool to try to find Hermione. Making their way to the girls’ restroom, they find Hermione under attack by the creature. Encouraged by Hermione, Ron performs a spell that uses the troll’s own club to knock him out. Not everyone is pleased (Quirrell is a double-agent, Snape is annoyed), but Professor McGonagall gives the lads points for saving their friend.

5. The Crow (1994)

The Crow trailer (Uploaded to YouTube by Movieclips Classic Trailers)

The supernatural revenge thriller based on the comic book series by James O’Barr found tragedy in the on-set death of leading man Brandon Lee and triumph in the critical and financial success of the film and its soundtrack. The plot turns around October 30th, once known as Devil’s Night in Detroit for a phenomenon of arsons taking place on that date over several decades; on one Devil’s Night, Eric Draven and his fiancée, Shelly, are murdered on the day before their wedding (which would have been Halloween). Draven returns one year later to deal out harsh vengeance on those responsible. The city, already portrayed in a dark and gothic manner by director Alex Proyas, also has the trappings of Halloween, including trick-or-treating children that pass Draven in costume.

4. Watchmen (2009)

Watchmen trailer (Uploaded to YouTube by Legendary)

Based on the medium-changing comic book series by Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons (seriously; it’s on Time’s list of 100 Best Novels from 1923 onward), Zach Snyder’s Watchmen takes great pains to present an adaptation that’s as close to the page and panel as possible. The story takes place in an alternative 1985 where Nixon is still president and America won the Vietnam War thanks to the intervention of the super-powered Dr. Manhattan. Though the story constantly jumps in time, the main narrative is set in 1985 on the verge of Halloween . . . and nuclear holocaust. Halloween imagery sneaks in at the edges, and several critical plot developments (many of which are horrifying in their own right) occur across October 31 and November 1.

3. The Karate Kid (1984)

The trailer for The Karate Kid (Uploaded to YouTube by Movieclips Classic Trailers)

One of the more memorable Halloween scenes from any high school-related film happens in The Karate Kid. At a Halloween dance, Daniel (Ralph Macchio) wants to be with Ali (Elisabeth Shue), but he’s been trying avoid the bullying of Johnny and his Cobra Kai buddies. Daniel cleverly dresses in a shower costume to conceal his identity. But when Johnny breaks off from the other Cobra Kais (who are all dressed in matching skeleton costumes and facepaint) to smoke weed in the bathroom, Daniel takes the opportunity to rig up a hose and douse Johnny. The Cobra Kais chase Daniel down and deal him a violent beating until Mr. Miyagi (Noriyuki “Pat” Morita) intervenes. Miyagi dismantles the bullies by himself and helps treat Daniel’s injuries. Soon after, Miyagi begins to train Daniel so that he can confront the Kais at the All-Valley Tournament.

2. E.T. (1982)

The Halloween scene from E.T. (Uploaded to YouTube by Movieclips)

Is there anyone who doesn’t know E.T.? What you might not recall is that Halloween actually plays a crucial role in advancing the plot. E.T. wants to “phone home” so that his people can come back for him. However, Elliott and his brother Michael need to sneak E.T. and the communication array he’s built to the nearby woods where they’ll have a better chance of making contact. That’s where Halloween comes in. The boys use that most reliable of disguises (from a kid’s point of view): a white sheet ghost costume. They first have to convince their mother that they’re actually taking their little sister, Gertie, out, which works. Although a chance encounter with a kid dressed as Yoda distracts the alien, they are still able to get him to the forest to make his call.

1. To Kill a Mockingbird (1962)

The Halloween attack from To Kill a Mockingbird (Uploaded to YouTube by Movieclips)

Speaking of important scenes occurring at Halloween . . . the climactic action of To Kill a Mockingbird happens on Halloween night after a pageant where Scout is dressed as a giant ham. As Scout and her brother Jem walk through the woods toward home, they are attacked. Scout can’t see much because of her costume, but she realizes that someone else stopped their attacker. It soon becomes clear that they were attacked by Bob Ewell, whom Atticus had shamed in court. The man who saved them was their reclusive neighbor, Arthur “Boo” Radley. As Atticus and Sheriff Tate piece together events, they realize that Boo stabbed Ewell, killing him. However, Tate decides to list it as an accident, sparing Boo the attention and circus of a trial.

Featured image: leolintang / Shutterstock

Dark Knight, Dark Theater: 75 Years of Big-Screen Batman

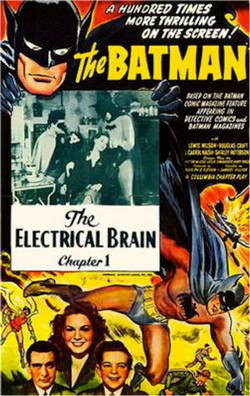

Adam West. Michael Keaton. Val Kilmer. George Clooney. Christian Bale. Ben Affleck. Lewis Wilson. Wait . . . Lewis Wilson? That’s correct. The first actor to play Batman on the big screen, Wilson starred in the serial Batman, released 75 years ago this week in 1943.

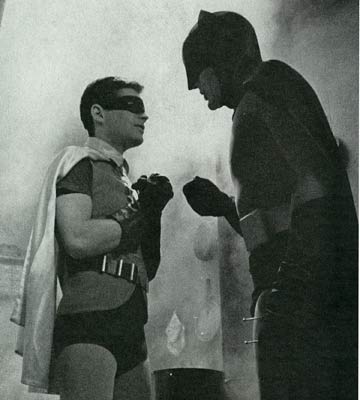

The Columbia Pictures serial followed a pattern typical of the format at the time: There were 15 chapters of roughly 17 minutes each, with a new installment released weekly ahead of features at the theatres. While the black-and-white production might look cheap and dated to modern audiences, Columbia invested more in Batman than in any of their other pictures at the time, and gave it a marketing push equal to that of their regular features. Critics of superhero film hype probably need to start here.

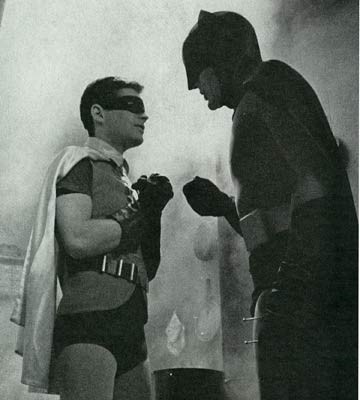

Batman attracted positive attention from fans of the Caped Crusader because it remained faithful to the general principles of the comics created by Bob Kane and Bill Finger, among others. Unlike the Republic’s Captain America serial of 1944 — which changed Cap’s origin, secret identity, and costume and replaced his shield with a gun — the Columbia take on Batman took pains to stay close to the original. Batman was millionaire Bruce Wayne, Robin (played by Douglas Croft) was Dick Grayson, and Alfred was, well, Alfred (played by William Austin). In fact, after the serial’s success, the portly Alfred of the comics was changed to resemble the thin, mustachioed Austin. The serial indelibly added to the mythos by showing Batman and Robin operating out of a Batcave under Wayne Manor.

The original trailer for the 1943 Batman serial.

One notable change was a result of film censor rules of the time. Since various offices disapproved of vigilantism in films, Batman and Robin were given a government agent affiliation for the purposes of this particular adventure. It’s a minor thing in retrospect, and not terribly dissimilar to Batman’s relationship with the Gotham City Police Department in the later 1960s television series.

The plot’s pretty standard for action serials of the time: the villain, Dr. Daka, is the Japanese leader of an Axis saboteur ring, and Batman and Robin are out to stop him. What makes the serial stand out, apart from decent attempts at costumes, are set pieces that include the gadgetry and traps that would become hallmarks of Batman in the comics and on screens large and small. Daka meets his end falling through a trapdoor into a pit of crocodiles (although writer Roy Thomas used him in the 1980s for a brief run in All-Star Squadron, a book that dealt with DC heroes in World War II).

Columbia had a hit on its hands with Batman, and it led to the immediate green-lighting of a serial based on radio and comics character the Green Hornet. Unfortunately, The Green Hornet tanked at the box office, which was in part responsible for the delay in producing the Batman sequel, Batman and Robin, which didn’t come until 1949, with a different cast. Ironically, Green Hornet would, like Batman, later be featured in a TV show in the ’60s, and they would even cross over in a two-part episode in 1967.

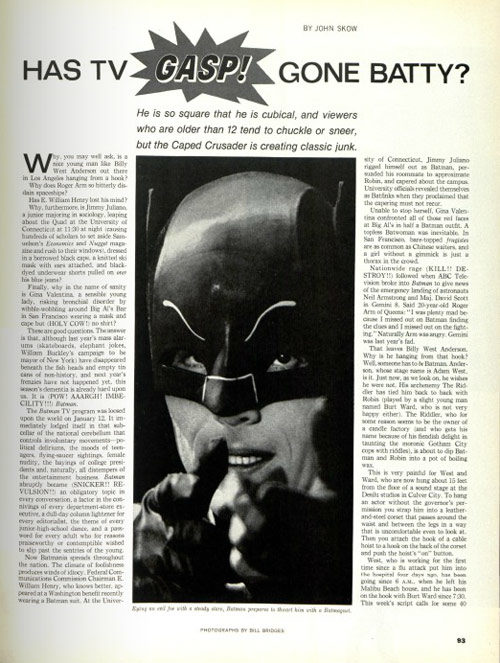

For on-screen appearances, Batman remained on the bench through the ’50s, even as the comics continued their ongoing run. He hit the screen again in a big way in 1966, when Adam West brought him to life for the Batman TV series. As it hit new heights of popularity, The Post visited the set for the May 7, 1966 article “Has TV (GASP!) Gone Batty?”. The series ran for three seasons and spun off a feature film, Batman: The Movie, in 1966, as well.

After the campy show came to a close, Batman spent most of the ’70s and ’80s confined to animation, regularly appearing on the various seasons of The Super Friends from 1973 to 1986. West provided the voice of Batman for the final two seasons. West and Burt Ward (Robin) also reprised their roles for a pair of live-action specials in 1979.

But the big screen beckoned Batman again in 1989. Batman, starring Michael Keaton, Jack Nicholson (The Joker), and Kim Basinger (Vicki Vale), crushed the box office that summer, earning over $400 million. Warner Brothers launched a full-blown multimedia franchise at that point, including a rebooted animated take on the Dark Knight that resulted in subsequent spin-offs for Superman and the Justice League. The movies marched onward with Keaton again in Batman Returns (1992), Val Kilmer in Batman Forever (1995), and George Clooney in Batman & Robin (1997).

The first theatrical trailer for Batman Begins from 2005.

For a variety of reasons, Batman & Robin failed with the public. While the animation marched on, it would be eight years before another live-action Batman film. Director Christopher Nolan took the helm, assembling a cast of heavy hitters (Gary Oldman, Morgan Freeman, Liam Neeson, etc.) around Christian Bale as the lead in 2005’s Batman Begins. The hit film led to 2008’s The Dark Knight, a massive critical and commercial success fueled by the Oscar-winning depiction of the Joker by Heath Ledger, who would sadly die of an accidental overdose prior to the film’s release.

Batman continues to be a major film presence. After Nolan closed his trilogy with The Dark Knight Rises in 2012, a new version of the Caped Crusader emerged in Batman v. Superman: Dawn of Justice. The 2016 film gave us Ben Affleck in the role; he would return for Suicide Squad in 2016 and Justice League in 2017.

Presently, plans at Warner appear to be up in the air. Director Matt Reeves has the keys to the franchise and appears to want to, like Nolan, veer younger with his hero again. Whatever the case, it seems certain that Batman will never be gone from the big screen for long.

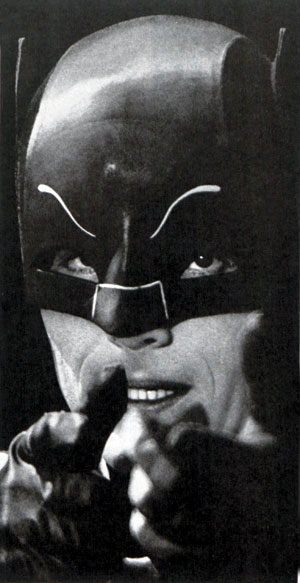

Remembering Adam West as Batman

We were saddened by the news this weekend of Adam West’s passing. Best known for playing Batman, West got his start on a TV variety show and had parts in such movies as The Young Philadelphians and Mara of the Wilderness. He also played the lead in The Detectives TV series.

But Batman was his big break, even if he didn’t know it at the time. In 1966, John Skow wrote an article for the Saturday Evening Post where he explored the phenomenon of Batman, which ABC had launched in January in a bid to gain ratings.

Skow writes of a conversation with West:

What was your reaction when you heard about Batman? I asked West at lunch. “My reaction was Ecch!” he said. But Batman had turned out to be fun. “You have to take it seriously,” he said. “I want to do it well enough that Batman buffs will watch reruns in a few years and say, ‘Watch the bit he does here, isn’t that great?”

Executives feared the show would be too silly for adults, but their fears were unfounded. According to the article, sales for Batman merchandise were expected to reach $75-$80 million, 50 percent more than the best year for James Bond.

What no one could know at the time is that Batman would spawn an empire of comic books, TV remakes, and blockbuster movies. But it all started with the dead-serious camp of Adam West.

Pow! Bam! Zonk!

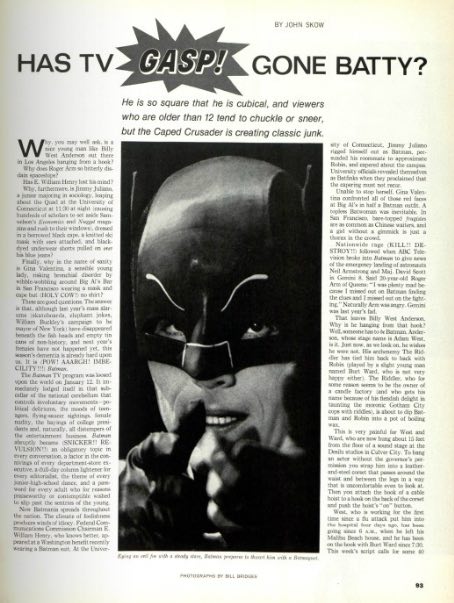

Excerpt from “Has TV (GASP!) Gone Batty?” by John Skow

Originally published on May 7, 1966

The Batman TV program was loosed upon the world on January 12. It immediately lodged itself in that subcellar of the national cerebellum that controls involuntary movements. … Batman abruptly became (SNICKER!! REVULSION!!) an obligatory topic in every conversation … a dull-day column lightener for every editorialist, the theme of every junior-high-school dance. … Before Batman, Adam West’s knockabout acting career had taken him to Hawaii, where he spent four years as an actor/director for a TV variety show. … Then came Batman, and for the first time in West’s life, people were turning around in restaurants to look at him. He accepts the stares cheerfully and with remarkable balance. … “What was your reaction when you heard about Batman?” I asked West at lunch. “My reaction was Ecch!” he said. But Batman turned out to be fun. “You have to take it seriously,” he said. “I want to do it well enough that Batman buffs will watch reruns in a few years and say, ‘The bit he does here, isn’t that great?’”

The Curious, Campy Success of Batman

The year was 1966, and television was starting to take itself less seriously. Programs like The Man From U.N.C.L.E. and The Wild Wild West were lightly satirizing action shows by introducing outlandish plots, ridiculous villains, and impossible gadgets.

No show took the concept of self-parody farther than Batman, which premiered in 1966. It purposely exaggerated every cliché of the detective story. Yet, as John Skow pointed out in his May 1966 Post article, it was among the most popular programs of its day. So popular that, when ABC interrupted an episode to report on the emergency return of the Gemini 8 space mission, the network was flooded with protests from outraged fans.

Batman quickly became more than just entertainment. It became the country’s biggest fad. References to the show popped up in conversation and worked their way into late-night talk shows. Everyone seemed to be enjoying this jokey version of a comic book hero. Sales of Batman merchandise in 1966 exceeded $75 million—about 60 percent more than James Bond merchandise had earned in any year.

Unlike the action hero Bond, Batman was purely a comic hero: a parody of every good guy on TV. He was improbably strong, brave, and virtuous to the point of being preachy, as in this typical exchange with a villain:

RIDDLER: “With you two out of the way, nothing stands between me and the Lost Treasure of the Incas … and it’s worth millions!! Hear me, Batman, millions!”

BATMAN: “Just remember, Riddler, you can’t buy friends with money.”

No laugh track accompanied such lines, but viewers quickly lost any doubt they were watching a comedy.

The look of the show—low-budget sets painted with comic-book colors—was heavily influenced by the Pop art craze. Starting in 1962, Pop artists used images from popular entertainment and advertising to ironically reflect American culture. (Remember Andy Warhol’s Campbell’s soup can?) The show’s chief writer, Lorenzo Semple Jr., chose a Pop art style as his protest against conventional TV programming. Serious dramatic shows, he said, relied on semi-truths and evasion. “We started out to do a Pop-art thing and we’re doing it.”

The mocking of the superhero figure also reflected the rise of “camp” humor. Camp emphasized the cheap, gaudy, and sentimental elements of popular culture. It was never meant to ridicule. The purpose was to ‘make fun with’ not ‘make fun of’ popular icons. (However, Skow believed camp humor was “mean spirited … a jeering private laugh at anyone square enough to take the pretension seriously.”)

Another influence on Batman the TV show was the public reaction in the 1950s against violence in comic books. Responding to pressure from parents and educators, publishers established the Comics Code Authority, which prohibited any references to brutality and gore.

The show took the new comic code even farther by eliminating any hint of violence. Batman was no more dangerous than a pillow fight with very small pillows. The crimes, committed by a gallery of returning characters, would involve stealing something, or taking over Gotham City’s government (in order to steal something). No one was ever murdered on the show. There was nothing more brutal than “comic violence”—burlesqued fistfights in which the words “Pow,” “Bam,” and “Zap” appeared in large, comic-font letters. And Batman always triumphed in the end.

For a while, this satire on a popular comic book hero was a successful formula. By 1968, however, the novelty had worn off and the last show aired 45 years ago this week.

It wasn’t a bad run. The show had been an audacious gamble with viewers’ indulgence. It had assumed, as Skow expressed it, “there was nothing that could make the adult American television watcher feel silly.”

The year that Batman disappeared for the last time into his papier-mâché Batcave, a new crime-fighter rose to the top of the TV rating: the tough, dedicated, but always cool hip Steve McGarrett of Hawaii Five-O.

Batman, of course, didn’t disappear. The comic books are still in print, though they are less restrained in their use of death and violence. The movie versions have become increasingly morose. The most current version, starring Christian Bale, who may be returning in a Justice League movie, is a grim, solitary loner. The caped crusader of the 1960s would barely recognize himself today.