Cartoons: A Day at the Beach

Want even more laughs? Subscribe to the magazine for cartoons, art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

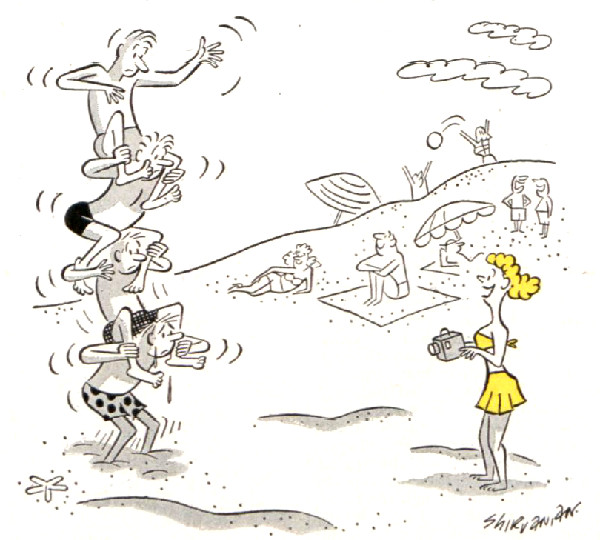

Vahan Shirvanian

August 9, 1952

Hoff

July 14, 1951

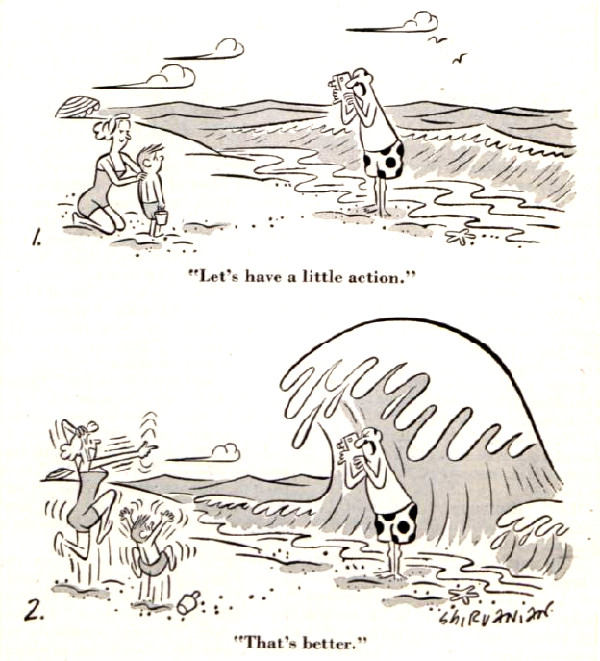

Frank Ridgeway

August 18, 1951

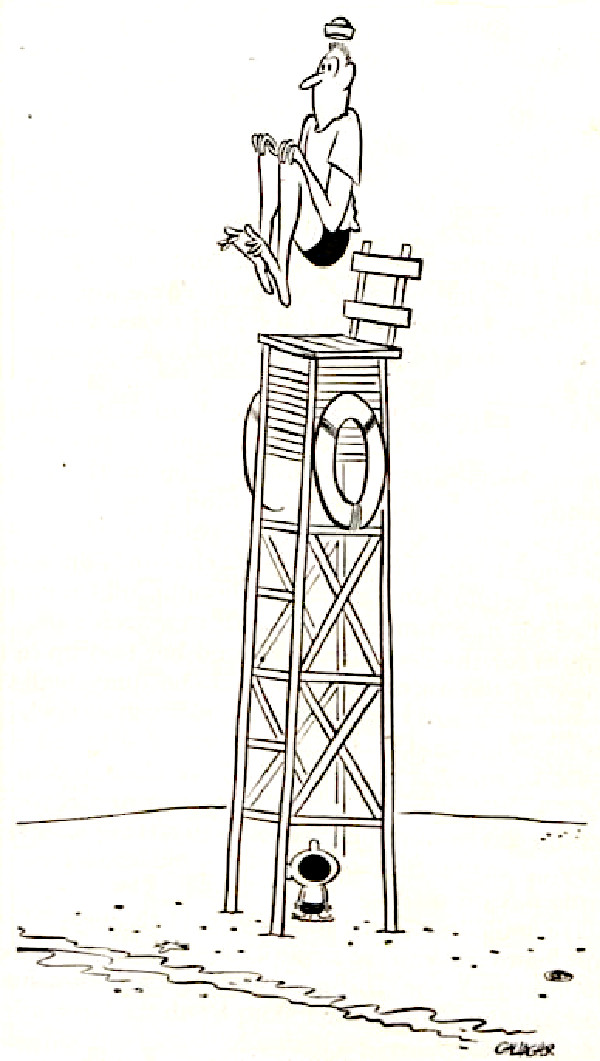

Gallagher

August 16, 1952

August 14, 1952

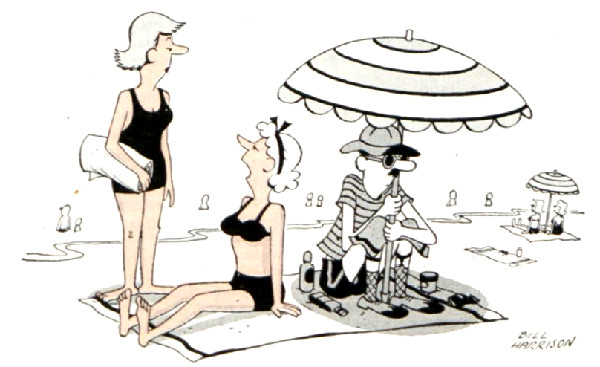

Bill Harrison

August 9, 1952

Want even more laughs? Subscribe to the magazine for cartoons, art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Cover Gallery: A Day at the Beach

These beachgoers on the covers of the Post are having the dream summer vacation.

Ellen Pyle

August 7, 1926

The Saturday Evening Post was the first magazine to accept Ellen Pyle’s work after her husband’s death in 1919. “The girl I am most interested in painting is the unaffected natural American type,” Pyle said in her 1928 interview with the Post. Her children often posed as models for Pyle’s paintings, but it was her brilliant use of color and loose, broad brushstroke style that made her one of the Post’s most recognizable female artists.

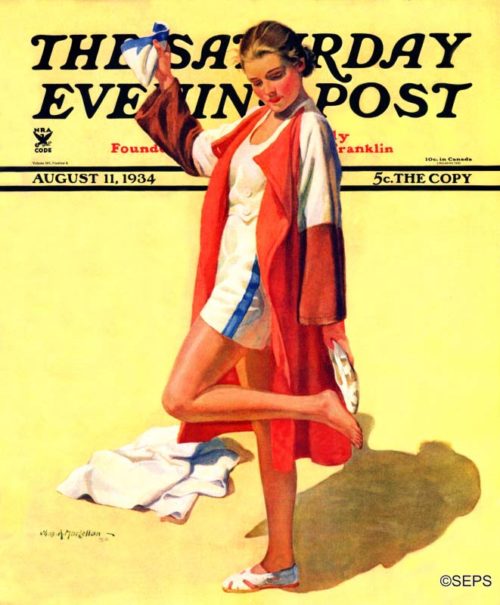

Charles A. MacLellan

August 11, 1934

Charles A. MacLellan started creating art for the Post during a time when narrative illustrations dominated the covers. His most memorable covers were those with children, typically boys. Often these boys were in some kind of trouble, but it’s the kind of trouble that makes their viewer smile. In his portraits of women, MacLellan nearly always drew them in action and often gave his models a prop, such as this woman and her beach clothes.

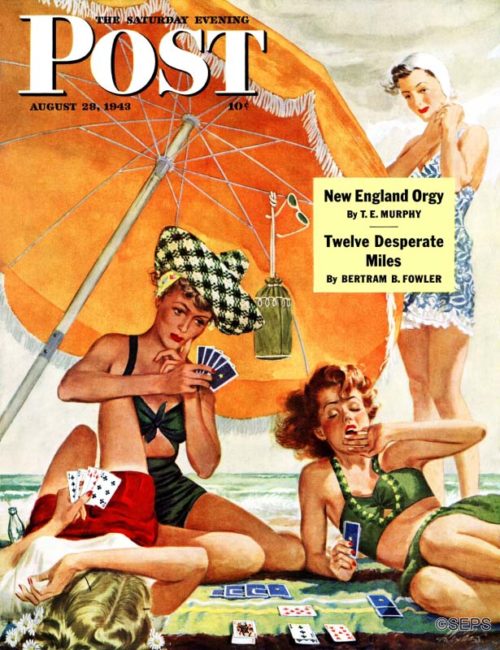

Alex Ross

August 28, 1943

This is one of six covers that Alex Ross painted for the Saturday Evening Post. All of his covers featured beautiful women, but this beach scene is the only one that doesn’t focus on a single girl. This 1943 cover does follow Ross’ usual style, however, because the women don’t appear to be over-joyed about their card game.

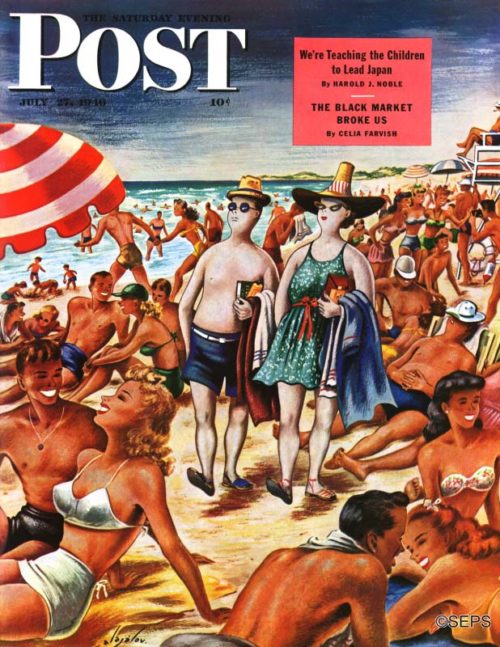

Constantin Alajalov

July 27, 1946

Constanin Alajalov’s painting of the new arrivals picking their green and embarrassed way through the tanned regulars, could have been made on any beach in the country. For that feeling of outstanding pallor is well known from coast to coast, and there is no lotion for it, except that in a few days you can sneer at even later arrivals. Alajalov made his sketches in Palm Beach, Florida, when the Northerners were arriving last winter.

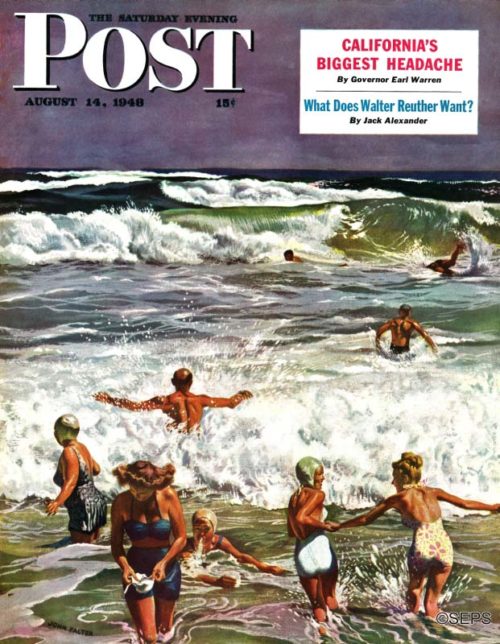

John Falter

August 14, 1948

Artist John Falter’s setting for his surf-bathing cover is Ogunquit, Maine. He made his first sketches while spending the summer in Maine, but didn’t get around to painting until last winter. By that time the lucky lad was in Phoenix, Arizona. The hotter that Arizona sun got, the more fondly the artist thought of Maine’s cool air and cool spray. So he went to work on a picture of Maine as remembered in the Southwest. The pretty girl in the left foreground, just emerging and shaking out her hair, often appears in Falter’s cover paintings. But doesn’t get a model’s pay for her work. She is Margaret Falter. John’s wife.

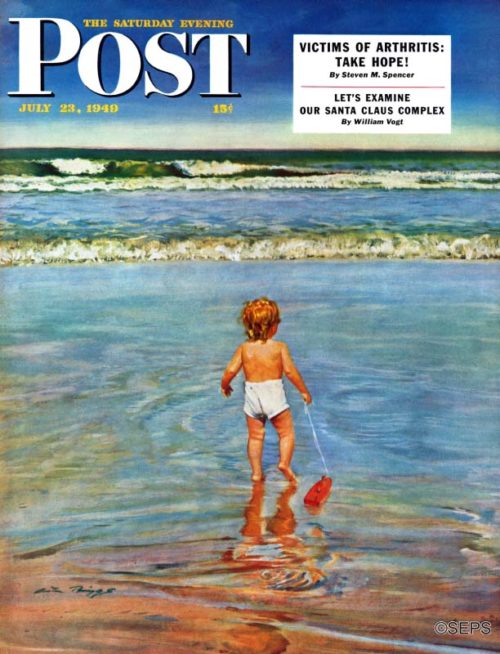

Austin Briggs

July 23, 1949

Don’t worry about the tiny cover girl who is going down to the awesome sea with her eight-inch ship. Just as Austin Briggs, who was vacationing at Folly Beach, Charleston, South Carolina, spied the seagoing tot, her mother let out a yelp and splashed into the foam after her. Now there, thought Briggs prophetically, could be my first Post cover.

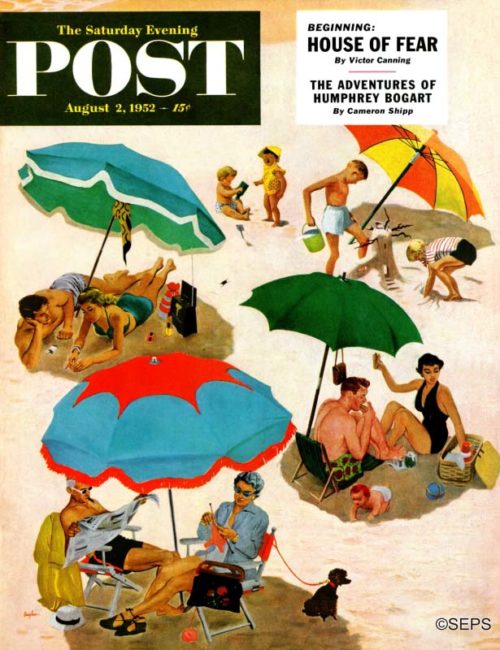

George Hughes

August 2, 1952

In the winter, people buy sun lamps to get sun, and in the summer they buy beach umbrellas to keep the sun off. Well, have a wonderful time, folks; build your sand castles and your dream castles; let the cool winds and the hot dogs renew you; and don’t even let the annoyment creep in if that boy’s radio prevents your hearing the sweet nothings he whispers to his girl. Now turn the page, before the kids start throwing sand.

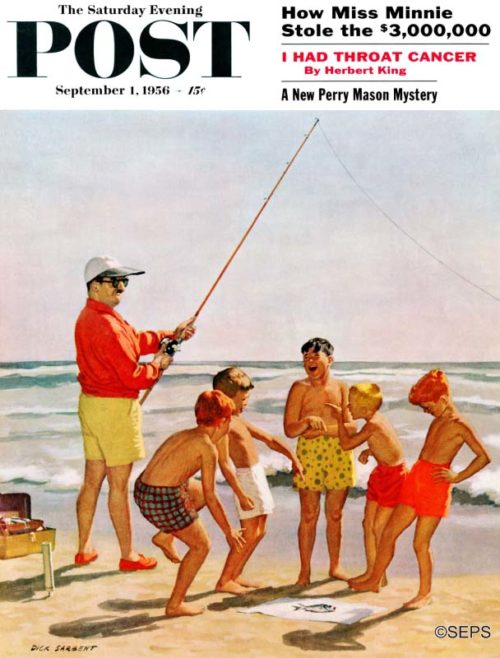

Richard Sargent

September 1, 1956

Mr. Rodney Fischer, an eminent metropolitan banker who is accustomed to being treated with deep respect, is not being. If that is a sardine he has caught, it may cop the surf-casting championship, for it is indeed of great size. But the boys’ happy faces and the man’s apoplectic face indicate that it is a small sample, or child, of something more ambitious. Mr. F. should set his rod in the gadget Dick Sargent has painted behind him, and lie down and relax his bile; if he goes to sleep, he may catch something decent. While he stands up, his blinding raiment must terrify all the fish who are old enough to think.

America’s 10 Best Beaches

I’m on my hands and knees scouring the beach for diamonds. It’s a picture-perfect summer day: sunny and warm, with practically no humidity and maybe the biggest blue sky I’ve ever seen. The beach is heavenly, with that sugar sand you find in the tropics, framed by a dune forest protecting the scrub-shrub habitats of nesting songbirds.

Diamonds — well, actually, beautiful, translucent pieces of quartz — are abundant, but that’s only a small part of the draw. There’s the privacy (it’s one of the region’s most sparsely populated beaches); the splendid bird watching (rated by Audubon as one of the best birding sites in the nation), and that special sand. Who knew that this slice of paradise — Higbee Beach in Cape May, New Jersey — is within a five-hour drive of one-third of the U.S. population?

The plain truth is the United States is a treasure trove of these magnificent hideaways. Following are some of the best in the country, selected with a bias toward geological uniqueness, magic, and unspoiled beauty. All you need bring is a towel and a picnic.

1 Pauoa Beach

Where: Kohala Coast, Hawaii

Wow factor: Ever dream of bathing in champagne? The beach fronts a postcard-worthy coral reef cove, where cooling freshwater springs bubble up from the bottom of the warm Pacific Ocean, making you feel like you are swimming in a bathtub filled with Fizzies. Later, while lounging on the warm sand, dig your feet down deep and feel the freshwater spritzing up.

Sand: The expanse of soft, pearl-white granules is flecked with colorful bits of coral, shells, and lava.

What to collect: Souvenir photos. Removing the lava that has bubbled up along the beach is illegal; worse, doing so is cursed by Pele, the Hawaiian goddess of fire.

Local lore: A five-minute walk from the beach is the Puako Petroglyph Archaeological Preserve with over 3,000 engravings. Archaeologists believe these petroglyphs depict life events of the local culture thousands of years ago.

When to go: Anytime. Daytime temperatures hover in the 70s and 80s year-round.

Stay: The beach resides on the grounds of the Fairmont Orchid (fairmont.com/orchid), which offers rooms with ocean views and private lanais.

Eat: Innovative farm-to-fork Pacific Rim fare is almost beside the point compared to a sunset show at Napua Restaurant (napuarestaurant.com); dinnertime guests get to watch stars light up the Kohala coastline after seeing the sun melt into the Pacific Ocean.

2 Bandon Beach

Shutterstock

Where: Bandon, Oregon

Wow factor: Sandwiched between dense forest and the Pacific, the beach offers dramatic views of rock pillars (known as sea stacks) jutting from the ocean, as well as small islands inhabited by nesting seabirds, birthing seals, and more. Don’t be surprised if you happen upon a sea lion having a splash.

Sand: Fine heather-toned grains pack well for castle building.

What to collect: Agates. At least 20 varieties including carnelian, moss, and cloud.

Local lore: According to legend, the curious rock formations along the beach were formed when a mountain chief brought his daughter to the shore for the first time. Ignoring the warning that looking at the evil ocean spirit Seatco would turn her to stone, the daughter wandered the beach and was frozen in place.

When to go: Year-round. Frigid water and wind prohibit this from being a swimming beach; come dressed in layers as storms can kick up unexpectedly.

Stay: Every room and private cottage at Windermere on the Beach (windermereonthebeach.com) have beach access and panoramic views of the Southern Oregon coastline.

Eat: Bandon’s best scene for a sunset cocktail is The Loft (theloftofbandon.com), which sits atop the High Dock building and serves exquisite Pacific Coast-fusion cuisine.

Shutterstock

3 Pfeiffer Beach

Where: Big Sur, California

Wow factor: Front and center in the crashing surf is Keyhole Rock, a gargantuan arch with waves hurtling through the center split. In winter, catch it just before dusk and see the setting sun cast its final rays through the keyhole.

Sand: The purple sand, located at the north end of the beach, draws its unusual color from manganese garnet fragments, eroded from deposits in the hills, that become finely ground as they wash onto the beach from the creek above.

What to Collect: Well, the sand, for starters. Diligent beachcombers can often find sizable chunks of manganese garnet that has been washed from the cliffs above onto the beach. But note: Digging into the rock face is prohibited.

When To Go: Wind gusts are common here year-round, but less harsh during the drier months, June–October.

Local lore: Big Sur’s dramatic landscape has been the setting for countless feature films, including according to Hollywood legend the famous kiss between Burt Lancaster and Deborah Kerr in From Here to Eternity.

Stay: For comfort and panoramic views, you can’t go wrong with Post Ranch Inn (postranchinn.com). The more adventurous will stay in the treehouse lodgings stilted nine-feet above the forest floor, where there’s still plenty of luxe with spa baths, fireplaces, and wood decks facing the forest.

Eat: Cliff-dwelling eatery Nepenthe (nepenthebigsur.com) was once a cabin owned by Orson Wells and Rita Hayworth. Now it’s the ideal spot for mojitos at sunset.

4 Cape Hatteras Lighthouse Beach

Shutterstock

Where: Buxton, North Carolina

Wow factor: The beach is part of a narrow barrier island jutting 30 miles into the Atlantic, so its landmass is forever changing. What’s most striking, however, is the “magic fairy dust” that gets kicked up with each shuffling step in the sand. At night, you’ll find yourself surrounded by a spellbinding blue-green sparkle caused by microscopic phytoplankton that glow when disturbed.

Sand: The cape is a convergence of two major ocean currents, the cold Labrador Current from the north and the warm Gulf Stream, which grind bivalve shells into fine, soft particles.

What To Collect: Shells galore — knobbed whelks, Scotch bonnets, augers, baby’s ears, and more.

Local lore: The Grey Man of Hatteras is a shadowy ghost who walks the beaches. As the story goes, he’s the spirit of a sailor who perished at sea.

When To go: Beach weather here spans spring, summer, and fall, thanks to the Gulf Stream that blows warm breezes in chillier months. Locals especially love autumn, with its lazy Indian summer afternoons, but the threat of hurricanes lurks through September.

Stay: The waterfront Inn on Pamlico Sound (innonpamlicosound.com) is a boutique hotel with island-style guest rooms, an oceanfront swimming pool, complimentary kayaks, and a gourmet restaurant.

Eat: Come to Dinky’s (villagemarinahatteras.com/DinkysGenInfo.html) for the local catch, and you’ll be treated to the best show on the island — sunset.

National Park Service

5 The Beach at Sunken Forest

Where: Fire Island, New York

Wow factor: Just over the dunes behind this uninhabited beach on the famous barrier island between Great South Bay and the Atlantic Ocean is a rare maritime forest of stunted plant clusters, visible from a boardwalk. This stunted, or “sunken,” effect is caused by saline mists from the ocean.

Sand: The soft, reddish sand is made up of fine white quartz, laced with minute red garnet and black flecks of magnetite.

What to Collect: Sand. If you want to amuse your kids, take a magnet to it and show them how the particles magically float up.

Local lore: Historians and locals have debated the origin of the name Fire Island for decades. Many believe that it was a misspelled translation of Five Barrier Islands from a 17th-century Dutch map. (The number of inlets changes periodically with the weather.)

When To Go: Late spring to early fall is when the beach is warm and the forest in bloom. The ferry from Sayville, Long Island, to Sailors Haven runs only mid-May–mid-October.

Stay: No hotels in Sunken Forest. But a few miles (and short water taxi ride) down the island is the chic Palms Hotel in Ocean Beach (palmshotelfireisland.com).

Eat: If you stay in Ocean Beach, try Maguire’s Bayfront Restaurant (maguiresbayfrontrestaurant.com), as much for the spectacular sunset views as for the cuisine.

6 Peterson Beach

Shutterstock

Where: Sleeping Bear Dunes National Lakeshore, Michigan

Wow factor: Once named “the most beautiful place in America” by Good Morning America, Peterson Beach fronts Lake Michigan’s crystal blue Platte Bay. From the shoreline are unobstructed views of Sleeping Bear Point and Empire Bluff’s billowy sand dunes, formed during the last ice age. Some dunes soar as high as 450 feet.

Sand: While most of the Great Lakes have rocky shorelines, this beach is known for its powdery, golden sand.

What To Collect: You’ll find plentiful samples of Michigan’s state stone, the mottled Petoskey stone (fossilized rugose coral). Take pictures; the National Park Service doesn’t allow removing natural elements from the park without a permit.

Local lore: The Native American-inspired Legend of Sleeping Bear holds that a mother bear and her two cubs were driven into Lake Michigan by a forest fire. After swimming for hours, mother bear reached the shore first and perched on a bluff to await the cubs, but they soon tired and drowned. The Great Spirit Manitou created two islands to mark the spot where the cubs disappeared and a solitary bluff representing the mother bear.

When To Go: While each season brings distinctive hues and vistas, summertime offers the most tolerable water temps (up to mid-60s) for swimming.

Stay: The lakefront Homestead (thehomesteadresort.com) offers a range of resort activities and lodging options.

Eat: Blu (glenarborblu.com), with panoramic views of Sleeping Bear Bay, incorporates local provisions into its eclectic menu.

Shutterstock

7 Padre Island National Seashore

Where: North Padre Island, Texas

Wow factor: The longest undeveloped barrier island in the world stretches 113 miles between the Gulf of Mexico and Laguna Madre, one of the world’s few hypersaline coastal lagoons. Unlike kitschy and crowded South Padre Island, no hotels or businesses clutter the untainted seashore bordered by a narrow dune ridge, coastal prairie, and tidal flats. The beaches are quite desolate, populated by rare, protected wildlife, including endangered turtles and some 380 species of birds. The highway ends 10 miles in, so adventurers in four-wheel-drive vehicles must cross the sand from one beach to the next.

Sand: Billowy white sand, laden with exquisite shells.

What To Collect: Shells — common arks, cockles, and quahogs — and colorful coquina mostly found on Big and Little Shell beaches. Park Service permits the removal of up to five gallons of shells per day.

Local lore: Padre Island is reported to be a prime hiding spot for pirate gold. (Too bad the National Park Service prohibits the use of metal detectors.)

When To Go: As one of the southern-most spots on the mainland U.S., even December can bring warm days. Considering the staggering heat and humidity of summertime and hurricane threat into the fall, locals prefer the months of February–April when precipitation is low and temperatures often hover around 70 degrees.

Stay: The modern oceanfront Sandpiper Condominium (sandpiperportaransas.com) is a welcome respite after a day of trekking around Padre’s primitive shoreline. The resort offers well-stocked units with kitchens and balconies, a pool, and beach loungers.

Eat: Snoopy’s Pier (snoopyspier.com) is a family-owned, beachfront eatery serving local catch prepared with family recipes.

8 Higbee Beach

Shutterstock

Where: Cape May, New Jersey

Wow factor: Cape May’s sugar-sand beaches are considered among the cleanest in the nation, sparkling clean, in fact. Some of that sparkle comes from sand laced with Cape May Diamonds — gorgeous, translucent quartz. The stones wash up on Higbee Beach from the upper reaches of the Delaware River. Higbee, at the tip of Cape Island, also contains the area’s only remnants of coastal forest, protected by dunes up to 35 feet high.

Sand: The shoreline is blanketed with that downy white-blond sand normally associated with Caribbean beaches.

What To Collect: Those diamonds, of course. The largest wash ashore during winter months, when the current is strongest.

Local lore: Kechemeche tribe believed the diamonds possess supernatural powers.

When To Go: May–mid-October.

Stay: Congress Hall (caperesorts.com/hotels/capemay/congresshall) is a sprawling, historic beach resort still operating in grand style.

Eat: The Washington Inn (washingtoninn.com), in a restored 1840s plantation house, features a menu of continental fare that changes daily to incorporate the local harvest.

Shutterstock

9 Moshup Beach

Where: Martha’s Vineyard, Massachusetts

Wow factor: Moshup (aka Gay Head or Aquinnah) is one of the few places on the East Coast where you can catch the sunset — rather than sunrise — from a sandy beach. This secluded shoreline of white sand and crystal-clear water is sometimes tinged red by the surrounding russet-colored clay Aquinnah Cliffs, encasing eons of ancient animal and marine fossils — whales, horses, even camels — in their auburn grooves. Smattered around the beach are age-old rocks worn smooth by the crashing tide, and pieces of lignite — scientists say from the Cretaceous period. The most scenic time is sunset, when the cliffs glow with terracotta hues.

Sand: Surrounded by multi-hued rocks and clay cliffs, the soft, white sand takes on a variety of shades throughout the day.

What To Collect: The brightly striated glacial rocks, fossils, and mud (with legendary healing powers) are protected property, so capture them with your camera only.

Local lore: Native Wampanoag tribal folklore attributes the unique geology to a giant named Moshup. He hunted whales and threw them against the cliffs; their blood turned the clay red and their remains are those fossils found today.

When To Go: Most visitors and businesses operate around the seasonal ferry schedules, which run from Woods Hole or Falmouth with regular service mid-May–mid-October.

Stay: The cozy guest rooms of the cliff-dwelling Outermost Inn (outermostinn.com), owned by musician James Taylor’s brother Hugh, provide spectacular three-way vistas spanning the Nantucket Sound.

Eat: In a rural garden overlooking the ocean, Beach Plum Inn (beachpluminn.com) incorporates local provisions into imaginative dishes.

10 Henderson Beach State Park

Shutterstock

Where: Destin, Florida

Wow factor: The beach here is known for its whitest-of-white, sugary sand. Plus, great fishing.

Sand: The ground-quartz sand washes down from the Appalachian Mountains via the Apalachicola River out into the Gulf of Mexico. From there, the sand drifts west in the currents, much of it settling here.

What To Collect: Dune rosemary, an edible, non-endangered Florida scrub, that sprouts fragrant lavender flowers in springtime.

Local lore: Destin calls itself the World’s Luckiest Fishing Village. Perhaps that’s because the continental shelf comes closer to shore in Destin than anywhere else in the state, allowing anglers to reach every depth of fishable waters more easily.

When To Go: April–May and September–November are when ocean temperatures range a comfortable 60–80 degrees.

Stay: Henderson Park Inn (hendersonparkinn.com), Destin’s only B&B on the beach offers romantic guest rooms overlooking the beach, gourmet breakfasts, box lunches, beach chairs, umbrellas, and bicycles.

Eat: For Gulf-shore gastronomy, accented with a Creole flair Louisiana Lagniappe (thelouisianalagniappe.com/destin) is a longtime local favorite. Hush puppies, jambalaya, blackened shrimp etouffee, it’s all here.

Beach Wars

Ben Adair parks on the narrow shoulder of a residential street in Malibu, California. We get out of the car and locate our landmark: a blue-and-white sign half-hidden among the branches of an avocado tree. Turning down a road marked “Private,” we come to a metal gate that says, “Right to pass by permission and subject to control by owner.” It looks locked but isn’t, so we twist open the knob and walk through.

“I feel a little naughty doing this,” I tell Adair, a 43-year-old radio producer who also co-owns a boutique software company called Escape Apps. We stroll along a row of cliffside houses, and he reminds me that what we’re doing is perfectly legal. “It is private property,” he says. “But there’s an easement, so we’re allowed to use it.”

We come to a shady plaza with wooden Adirondack chairs overlooking the Pacific. Climbing down a staircase, we reach Lechuza Beach, which is as stunning as Adair had promised. Bougainvillea and ice plant dapple the 75-foot bluffs. Gulls perch on rock formations that rise from the waves. Two young men toss around a football, but otherwise this state-owned beach is nearly deserted on a sunny Martin Luther King Jr. Day.

“Check this out, man,” Adair says. “It’s a beautiful day in January, a holiday, and you’ve got the beach to yourself.”

What enabled us to find this hidden, idyllic stretch — the scene of legal and political skirmishes since the 1970s, when homeowners installed metal gates without a state permit — was a smartphone app that Adair developed in 2013 with writer Jenny Price. California’s 840-mile coastline, from the high-tide mark down to the ocean, belongs to all of its residents. But reaching those beaches, especially in affluent Malibu, can be daunting for someone who doesn’t know where the access points are, or can’t distinguish the counterfeit no-parking signs from the real ones. That’s where the Our Malibu Beaches software proves helpful: “It gives people the tools,” Price says, “to use these beaches that belong to us.”

Price hopes the 42,000 people who have downloaded the app will help prevent wealthy beachfront owners from treating the coastline like their own “private Riviera.” She and Adair also hope the app will protect those owners by advising visitors where not to walk. Though the duo has no plans to expand into other regions, the California Coastal Commission is independently releasing its own statewide app, developed by former Facebook president Sean Parker as restitution for throwing a lavish wedding at Big Sur without a permit.

But the new technology has triggered a backlash from some homeowners. They worry that it will attract, as one resident told me, “yapping dogs and screaming children,” along with their litterbug parents, to beaches that are ill-equipped to handle more people.

Underneath these conflicting views lie deeper questions that echo far beyond Malibu: Who owns America’s coastlines? How much access does the public deserve? Does buying an expensive waterfront home guarantee quiet and privacy? Must property owners accommodate strangers who can only reach the surf by cutting through private land? Communities from California to Maine are struggling with these issues, which are rooted in almost 1,500 years of legal history. The debate triggers emotional reactions on both sides as homeowners’ wish for tranquility butts up against the public’s right to enjoy what — in most states, at least — is legally everyone’s.

The Roman Emperor Justinian laid the groundwork for modern beach access when he declared in the sixth century, “By the law of nature these things are common to mankind — the air, running water, the sea, and consequently the shores of the sea. No one, therefore, is forbidden to approach the seashore, provided that he respects habitations, monuments, and buildings.” This principle — that we collectively own the coast — found its way into the English, French, Spanish, and Mexican legal systems, which in turn inspired American law.

But every state interprets the principle differently. Most extend property rights to the high-water mark, a few to the low-water mark. Some allow the public to walk across private property for recreation; others restrict those easements to “fishing, fowling, and navigation.” Every year new questions arise. Do scuba lessons constitute “navigation”? Can the government require an easement in exchange for issuing a building permit? When a hurricane rearranges the shape of the beach, does the public’s right of way move too? If so, what happens to houses sitting in that new right of way?

And so, across the country, the battles rage.

In Massachusetts — where the law particularly tilts away from public access — residents of Harwich on Cape Cod are sparring over whether several homeowners can claim exclusive use of Bay View Beach, which has widened by hundreds of feet over the past century because of the construction of a tax-funded jetty. State Attorney General Martha Coakley has said that 200 years of court rulings favor the private property owners — and last April, Harwich’s selectmen abandoned their claim to the beach. A lawsuit between beachfront and back-lot owners continues.

In New Jersey, where some seaside towns use parking restrictions to keep non-residents away, conservation groups like the American Littoral Society and Surfrider Foundation have asked state lawmakers to offer shoreline-protection funds only to municipalities that improve public access.

And in California, venture capitalist Vinod Khosla was rebuked twice last fall for cutting off the only road to Martin’s Beach near Half Moon Bay. The beach is surrounded by dramatic cliffs and has been a favorite spot for surfers, smelt fishermen, and sea-lion watchers. Before Khosla bought the land in 2008, the previous owner charged a small entry fee and operated restrooms and a general store for visitors. Khosla, by contrast, locked the entrance gate and hired private security guards to enforce his no-trespassing sign. In September, a state judge delighted beach lovers by ruling the billionaire had violated the state’s Coastal Act and ordering the gate unlocked. The following week, Gov. Jerry Brown signed a bill directing a state agency to negotiate with Khosla for a public easement or right of way. If negotiations fail, the state may acquire access through eminent domain.

Still, the most famous battleground is Malibu — because of its scenery, its glamorous and wealthy residents, and its starring role in dozens of surfer movies. In one well-known case, music and film producer David Geffen, along with the city, sued the Coastal Commission in 2002 to prevent the opening of a public walkway connecting the Pacific Coast Highway to well-heeled Carbon Beach. Geffen had consented to the easement across his land when he received a construction permit in 1983. The walkway sat behind a locked gate for almost two decades as state officials looked for a nonprofit group to manage it. When they found one, Geffen charged the state with failing to perform an adequate environmental review. He also questioned whether the managing organization was up to the task financially.

Geffen dropped his lawsuit in 2005. Today, during daylight hours, anyone can enter the beach and stroll past palatial homes designed by celebrated American modernist architects Richard Meier and John Lautner.

Yet those who want to open Malibu’s beaches cite ongoing problems. Most of the accessways acquired by the Coastal Commission remain closed. Owners discourage parking with traffic cones, homemade signs, and illegal curb cuts. They post misleading directions along the beach about where the public may walk. At Point Dume Nature Preserve, a state park with 200-foot volcanic cliffs, visitors compete for about 10 parking spaces. And face-to-face confrontations persist. “I still occasionally hear about harassments,” says former Coastal Commission chair Sara Wan, a Malibu resident who was threatened by security guards, then approached by five sheriff deputies, for sitting on a public beach in 2003. “I hear about home-owners who come out and chase people off the beach.”

Most recently, in December a development firm agreed to stop charging a $20 walk-in fee to access the beach below its Malibu restaurant and mobile-home park. The Paradise Cove Land Co. also agreed to open a pier and stop banning surfboards after the Coastal Commission threatened it with $11,250 in daily fines. The company will still charge $40 for parking, though.

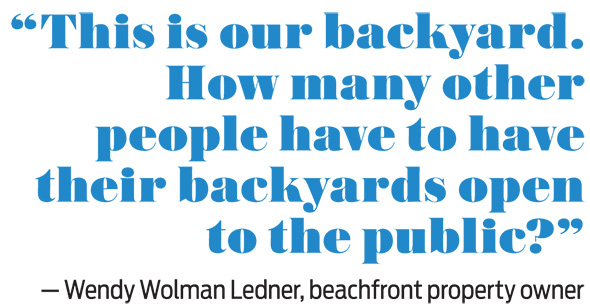

Some residents are candid about wanting outsiders to stay away. “I don’t see that every beach has to be open,” says Wendy Wolman Ledner, who is retired from the film and television industry. The public, she says, brings trash, noise, and unsupervised children who injure themselves, turning beachfront owners into first responders. They drape their towels over private decks, she says, and knock on residents’ doors when they need toilets. Ledner believes they’re better served by large county- and state-run beaches that have lifeguards, bathrooms, and parking lots. “If I weren’t one of the chosen — and please understand that I recognize I am very fortunate — and I had to get my water fix, I’d go to a public beach,” she says. “This is our backyard. How many other people have to have their backyards open to the public?”

Jenny Price, who co-developed the mobile app, says there’s a flaw in this argument: In California, the wet-sand beach is not the backyard of the adjacent landowners. “It’s kinda like the people who live next to Central Park saying, ‘You know, this is so close to our house and people leave trash here, so you really need to close off this park.’ People can live in a gated community and not have to deal with the public. But if you want to live next to the beach, that’s a really important public space, and you’re going to have to share it.”

Because they tap into big issues of property rights and social equity, and because so much is at stake for both sides, beach-access battles can divide communities and chill old friendships. That’s what happened in Kennebunkport, Maine, where beachfront owners sued the town to establish who controls a two-mile beach called Goose Rocks.

Unlike California, Maine allows residents to own property down to the low-tide line, and only grants automatic easements for “fishing, fowling, and navigation.” Neighbors or the general public can sometimes earn access for recreation, too — it’s called a “prescriptive easement” — by using the sand openly, continuously, and without explicit objection from the owner for 20 years.

Goose Rocks has been the site of many softball games, swimming lessons, and sand-dollar hunts; one traveler’s diary called it a “tourist resort” as early as 1870. A slice of the beach is owned by the town and a nonprofit conservancy. But much of the recreation has taken place on privately owned sand behind people’s houses, where beachfront owners mingled with back-lot residents and out-of-towners. “I never asked permission, was never given permission, never thought there was any necessity to ask for permission,” Richard Driver, a retired attorney who started coming to Goose Rocks in 1970 and now owns a house several blocks from the water, testified in a 2012 trial.

“It was kind of a secret beach,” says Robert Almeder, a retired philosophy professor who began vacationing there in 1979 and bought a beachfront house in 2005. “It was nice to see people playing on it.” But over the past 10 years, he claims, more people started arriving, and with them came noise, firecrackers, and tents for overnight camping. Hostilities reached a head in 2005 when a beachfront owner tried to order one of her back-lot neighbors off the sand. He refused to leave and police declined to intervene.

“If the right to private property means anything,” Almeder says, “it means you have exclusive control to determine how that property is used.” That includes the “freedom to go up and say: You need to leave now.” In 2009 he and some beachfront neighbors sued Kennebunkport to establish their ownership and property rights.

Back-lot residents felt blindsided by the lawsuit. “I have invested, and my neighbors have invested, tremendous amounts of money into this community,” Driver testified. “We live here, we love this place, and these selfish people come along. … All of a sudden a few of them decide, ‘Well, we want to restrict the beach.’” As hard feelings mounted, Almeder recalls neighbors saying, “‘I can’t be your friend anymore.’”

The town sided with the back-lot owners. It claimed that a century’s worth of recreational use had earned the public a prescriptive easement. After a two-week trial, a local judge agreed and declared Goose Rocks open to the public. In February 2014, though, the Maine Supreme Court overturned the 2012 ruling, saying the town failed to meet the state’s tough standard for obtaining an easement and that the lower court had gone too far in expanding the public’s rights. The high court cited Maine’s tradition of encouraging landholders to be generous with public use in exchange for having their property rights respected.

In December, though, the court authorized town attorneys to argue for beach access on a parcel-by-parcel basis. The lower court, which will hear those arguments, also still has to hear a claim by Kennebunkport officials that the town received title to the beach by royal grant in the 1600s and never relinquished it. For now, then, Almeder and his fellow plaintiffs have the right to evict others from their property.

No matter how the Goose Rocks case shakes down, no one believes it will settle the overarching question of who owns the beach, in Maine or anywhere else. “We’re going to keep litigating these on a case-by-case basis,” says Adam Steinman, a Portland attorney who represents the Surfrider Foundation, a leader in the national effort to improve public access. The beach, he says, “is a unique important resource, a public resource. If that resource is in control of the private few who stand to profit monetarily and socially by excluding the public, they’re going to do so. But that isn’t the way it’s supposed to work. Wherever beach access is at issue, we’re going to continue to fight for those rights.”