What We Can Learn from Gen Con

No one place is perfect. No large gathering or event is 100 percent without its troublemakers or people that negatively impact someone else’s good time. But for the 70,000 or so people that attended Gen Con in Indianapolis this past weekend, you’d be hard pressed to find a group that, en masse, found so much peaceful enjoyment in the commission of something that they loved.

For the uninitiated, Gen Con is “the longest-running and best-attended convention for tabletop gaming in North America.” Founded in 1968 by Gary Gygax, the co-creator of Dungeons & Dragons, as the “Lake Geneva Wargames Convention,” the original convention was held in Lake Geneva, Wisconsin. The main location remained in Wisconsin (with “auxiliary” installments occurring in other cities and countries) until 2003, when the regular annual spot switched to Indianapolis. Gen Con celebrates games of all types (board, card, miniature, role-playing, you-name-it), and its attendees are as passionate a group of fans as you’ll find anywhere.

While video, computer, and app-driven games continue to be huge business around the world, so-called “hobby games” have been experiencing a resurgence for the past several years. Pop culture site ICV2 found that the category pulled in over $1.5 billion last year, and the industry sales have doubled since 2013, with crowdfunding sites like Kickstarter helping to drive the discovery and sales of new games.

Role-playing games have also been having something of a cultural moment. Whereas TV shows might have used D&D for a joke in the past, popular shows like Stranger Things have made the game a big part of their characters’ lives. Celebrities like Vin Diesel regularly talk about their love of RPGs, too. Perhaps no bigger booster of D&D exists than True Blood/Magic Mike actor Joe Manganiello. After his wife, Modern Family star Sofia Vergara, hilariously outed him as a gamer on the 2017 Emmys red carpet, Manganiello quickly became one of D&D’s biggest ambassadors. In addition to fun appearances on talk shows, the actor started a RPG-related clothing line and created a gaming library and program for kids at the Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh. Earlier this year, Manganiello’s character, Arkhan the Cruel, whom he’d played since he was as teen, was made part of official D&D canon by the game’s publisher, Wizards of the Coast.

Joe Manganiello and Stephen Colbert talking D&D on The Late Show with Stephen Colbert. (Uploaded to YouTube by The Late Show with Stephen Colbert.)

Manganiello’s story may be well-known, but it’s by no means unique. Gaming in all of its forms is a community. It encourages people to come together for a common purpose of enjoyment. Gen Con is the ultimate expression of that idea. Instead of several people meeting for game night, it’s thousands congregating for hundreds of games on-site.

Ryan Lybarger, a long-time gamer and co-founder of Utility Games, attributes much of the appeal and happy vibe of Gen Con to the fact that it’s so many things in one. He says, “I don’t know about anyone else, but for me, it’s because I’m surrounded by people doing what they want to do with no concern for what anyone else thinks. Cosplayers rocking obscure characters? Check. [Table-top] RPGers finding the perfect zinc-alloy d20? Check. Learning how to write better at a seminar? Yup. I imagine a lot of folks have to hide who they really are on a daily basis; at Gen Con, you’re never the weirdest person in the room. And everybody is okay with that.”

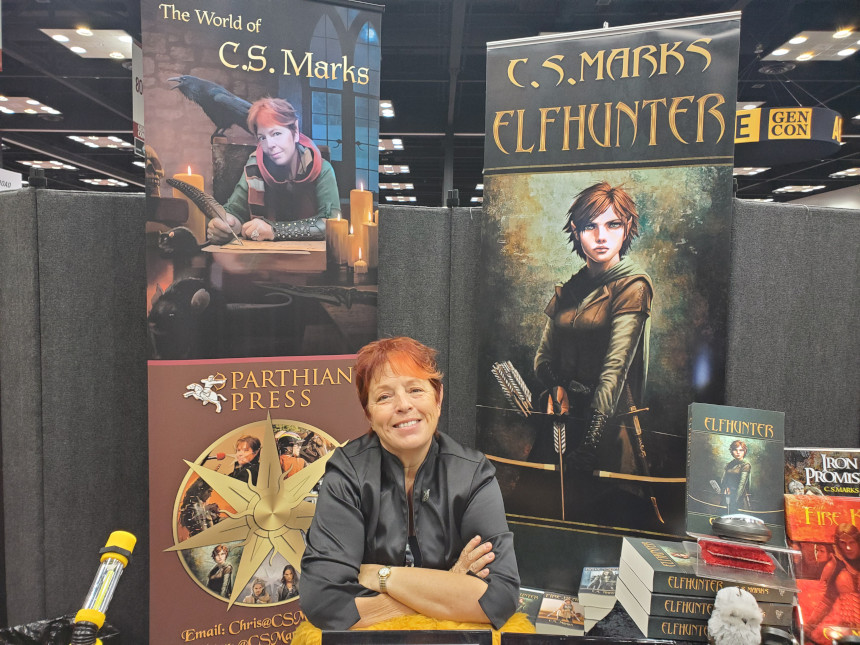

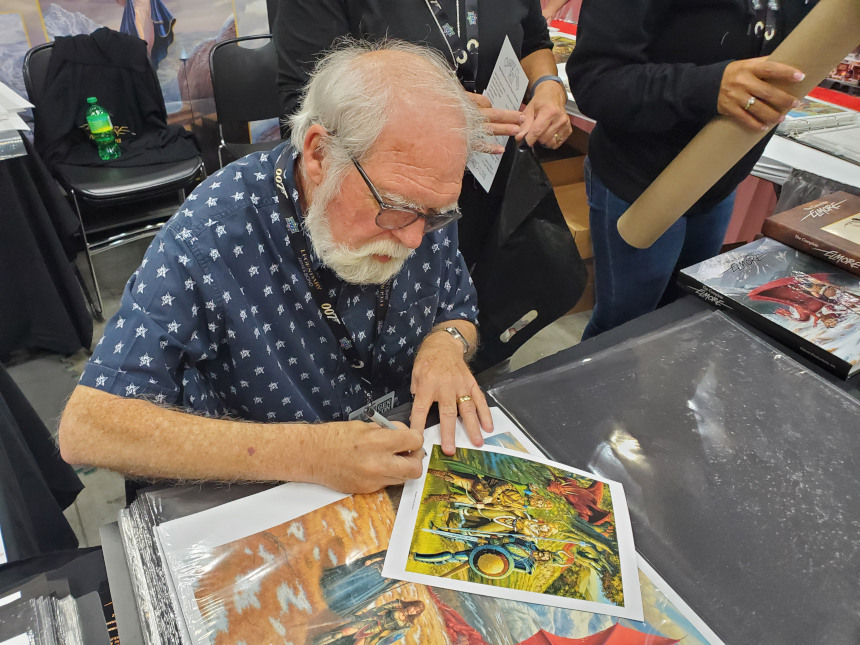

Lybarger certainly nails the “something for everyone” aura of the event. Tournaments and play-testing for innumerable games run constantly. Fantasy and science-fiction authors like Hans Cummings and C.S. Marks greet their fans. Highly regarded artists, like D&D and Dragonlance legend Larry Elmore, sign their work while producing new material at their booths. Vendors offer everything from medieval gear to Funko Pop figures. The biggest companies on the planet (like Mattel) have booths alongside start-ups that just put out their first game. It’s a swirling panorama of stuff that, for its devotees, is pure enjoyment.

Gen Con also exists as a nexus of different types of fandom. Anime, comics, and film characters are heavily represented in cosplay. Star Wars: Legion, a miniatures game, was very popular on the playing floor. Cryptozoic debuted and sold their DC Rebirth deck-building card game. Media tie-ins abounded.

However, perhaps nothing made as big a splash at the show as the announcement and demos for Marvel: Crisis Protocol, a new Marvel-based miniatures game from Atomic Mass Games. The game combines the hobby aspects of miniatures gaming (like painting the figures yourself) with a comprehensive game involving a wide range of familiar Marvel characters and terrain pieces.

As a whole, Gen Con exceeds its stated mission of being the best weekend in gaming. As Lybarger says, “[Gen Con is] greater than the sum of its parts. A trade show, by itself, would be okay. A game auction, by itself, would be fun. Hours of gaming, by itself, would be a blast. Add it all together, throw in seeing friends from far away . . . it’s bigger on the inside.”

And maybe that’s the most important thing. Over Gen Con weekend, Indianapolis was deep in throes of road construction that had been delayed by a rainy midsummer. As the fans descended on the town, important highways that led into downtown were closed, as was a vital street in the center of the city. It was inconvenient on a number of levels. And almost no one was complaining about it.

That’s because the idea and the essence of Gen Con is, simply, fun. How many things in our culture, at this precarious moment, can we say are just . . . fun? The list is, unfortunately, small. For 70,000 people to gather in one place and have a great time for four days isn’t just encouraging; it’s borderline miraculous. Maybe the lesson of Gen Con is that if more people just got together to do what they LOVE, instead of what they’re expected to do or obligated to do or made to do, then more people would have a better time. There’s no judgment at Gen Con. People get to be who they are, dress how they want, and play the games they like. Some people may dismiss that as childlike. That’s fine. We could use a little more childlike. American society lost its supposed innocence a long, long time ago. If we can get back a little bit of that spark of imagination, a little bit of that pure fun, even for just a little while, there’s never a way that can be a bad thing. In fact, that might mean that we’ve all won the game.

Featured Image: A diorama of the game Marvel: Crisis Protocol by Atomic Mass Games. (Photo by Troy Brownfield.)

A New Wave of Board Games is Breaking Parker Brothers’ Rules

Of all the industries shaken and destroyed by the fast-paced development of technology, one would assume board games to be sunk by their video counterparts. In reality, “tabletop gaming” is in the midst of a golden age. According to The Guardian, sales of board games is rising 25% to 40% each year.

Millennials aren’t necessarily playing Parcheesi, though. The new wave of games includes titles like Secret Hitler, Ex Libris, Dragonfire, and Pandemic. On the rise are role-playing games, connection games, Eurogames, and, sometimes, analog versions of existing video games, like Fallout and Sid Meier’s Civilization. Many are steeped in complicated fantasy worlds with Vikings and labyrinthine backstories, but others are simple logic contests. Still more are not competitive at all and only aim for players to work together in pursuit of a desirable conclusion. Yes, everyone can lose.

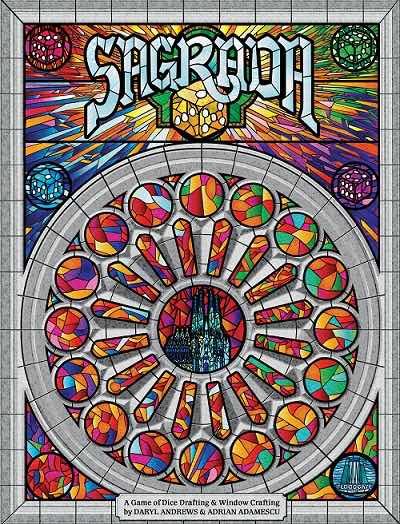

The internet has played a significant role in this revolution, creating a space for independent game makers to fund and sell their ideas. The independent tabletop game company Floodgate Games released their Spanish basilica-inspired dice game, Sagrada, this year after a Kickstarter campaign that raised over $150,000. The visually striking board game involves using colored dice to “construct a stained-glass masterpiece” with rules reminiscent of Sudoku.

Another Kickstarter success was the wildly popular — and risqué — Cards Against Humanity: A Party Game for Horrible People. Derivative of the family card-comparison game Apples to Apples, Cards Against Humanity ditched wholesome cultural and historical references for politically incorrect phrases like “demonic possession” or “a homoerotic volleyball montage,” or “actually taking candy from a baby.” The ribald and racy game earned an estimated $12 million in its first two years of production despite being free for download online (1.5 million downloads took place as well). The small Chicago group in charge of the debauchery continues to churn out expansion card decks, and they refuse to sell the brand.

Small-time board game publishers have seen enormous success given a platform to market and sell their games. This wasn’t always viable, though, with tabletop gaming. At the advent of commercial board gaming in the U.S., the late-1800s, Parker Brothers was the big name in board game development and manufacturing. Early games like Banking and Mansion of Happiness rewarded capitalistic pursuits and moral values.

In a Post story from 1966, “Pass Go and Retire,” Parker Brothers executives divulge their strategy of crowd-sourcing to find another Monopoly-tier hit: people from around the country would send their ideas with hopes that it would strike a fancy with the gatekeepers of fun.

“The inventors of successful board games are invariably amateurs, and not one has ever struck it rich more than once,” Parker Brothers disclosed. No one person was ever certain of what would become a hit, and the company relied on numerous test groups of various demographics. There were some gaming no-nos though, like witches and — early on — dice.

Pete Martin’s 1945 profile on Parker Brothers, which was located in Salem, Massachusetts, tells that “The game of Witchcraft was dropped when the embarrassed descendants of those New Englanders who took part in the seventeenth-century witch hunt asked that it be discontinued,” and, “Even as late as twenty years ago there were numerous parents who held that dice were instruments of the devil.” It is safe to say that Dungeons & Dragons would have been rejected vehemently.

Many newer board games laugh in the face of Parker Brothers’ old unwritten rules of what makes one popular: “A successful game should be simple, shouldn’t take too long to play, and even children should find it easy to learn.” In defiance of this advice, a 2016 cooperative game called Gloomhaven features a 52-page encyclopedia of a rule book whose contents are as foreign as a specialized medical textbook to those not in the know: “Monster statistic cards give easy access to the base statistics of a given monster type for both its normal and elite variants. A monster’s base statistics will vary depending on the scenario level.”

Still, for want of less time in front of screens or for lack of cash for extravagant entertainment, people keep playing games. Maybe it isn’t a consequence of anything other than the unbridled joy that they bring. One gamer wrote to Parker Brothers around 1966, “My cousin got married and went to Germany for her honeymoon, and she said they played Monopoly every night for enjoyment.” For some, the pastime has always been more than a necessity on a rainy day.

Check out the hidden history of Monopoly in the Post’s recent article, “Who Really Invented Monopoly?”