Peace in the Time of COVID‑19

Just when the death toll was at its steepest; just when the supply of hospital beds was dwindling, just as the novel coronavirus was scything through everyday life, canceling birthday parties, weddings, funerals, graduation, senior proms — a tall handsome man slit my throat.

I was lucky he was able and willing to do it.

Even during a pandemic, a few ugly words retain their power. “Metastatic” and “malignant neoplasm” are two of them. An inconveniently timed recurrence of my thyroid cancer put me in a rock-and-hard place situation: wait and let the cancer grow? Or have surgery at a time when everyone from my local Selectboard to the Centers for Disease Control was telling people to stay home? As the day for my procedure drew nearer, the COVID-19 news grew more and more dire. Each time the phone rang, I crossed my fingers that the hospital was not calling to cancel.

When the call finally came, I was told to be at the hospital at six in the morning. I was cranky about that — it meant leaving home by 4:30. But it turned out to be a blessing. That early in the morning, the hospital felt a little like an airport just when it opens, when the day is still clean and shiny, and schedules have yet to be upended by the vicissitudes of weather, traffic, and broken equipment.

But even in the morning calm, the weirdness of the “new normal” was apparent. At the front door, a sign announced that only patients were allowed in. So my partner, David, dropped me off and then drove the hour-and-a-half back home; there was nowhere for him to wait. Once inside, I followed tape marks on the floor to the registration desk, where all of the staff wore masks and HIPAA privacy rules went out the window: to pay my co-pay, I had to shout my insurance information and credit card number into the room where the clerk was working. In the surgery admission room, patients sat one to a table spaced six feet apart before being escorted one or two at a time to pre-op.

I was slightly disoriented. Since my previous surgery, the hospital had reorganized who did what where in order to keep coronavirus patients segregated. But perhaps not that segregated: over the course of the day, I kept hearing requests over the intercom for a respiratory therapist to go to the emergency room, “stat.”

But even down here deep in Alice’s rabbit hole — in this fun-house mirror version of a hospital — the mood was shockingly normal. After a few weeks of self-isolation, it seemed almost quaint to be in a place where people were actually interacting with each other. The nurses did the usual things — blood pressure, pulse, and so on — with the normal amount of touching followed by a new-normal amount of hand sanitizing.

My surgery went well. The anesthesiologist told me I “did great” — which (at least in my limited experience) is what they always say after surgery, although I don’t know what that means seeing as all I did I was lie on my back unconscious. It doesn’t seem like something to be good at, and I don’t think I will add it to my bio, but some days you take whatever compliments come your way.

In the recovery room, the man in the bed next to me was coughing loudly. The nurse said that this was common after anesthesia tubes are removed, but no one wants to hear coughing these days regardless of how normal it might be, so the nurse fast-tracked me to my room in the new wing, where the rooms are private and spacious and well-lit and quiet. They even have pull-out beds so that a friend or partner can stay overnight with you, although since they’re not allowing visitors right now, that was a moot point.

I wasn’t in any pain. I had my pacifiers — phone and tablet — and I thought I would do some Kindle reading or some online browsing, but I didn’t. There was a TV, and I thought I might check out the news or indulge in my secret addiction to the HGTV channel, but I didn’t. I just kind of lay there with thoughts chasing each other around my head: how grateful I was that I wasn’t in pain, that I was all alone, that my room was peaceful, that the corridor outside was quiet, that in the middle of this world-slanting pandemic I was able to have the surgery I needed, and that the nurse made sure I got some coffee to relieve the caffeine-withdrawal headache caused by the “no liquids after midnight” rule. Little things and big. I lay like that for a long time.

I am not a generally smiley person. I have lines in my forehead that may have been inherited from some grumpy Slavic forebear. Or perhaps they were self-inflicted — with me, being happy often involves a furrowed brow as I wrestle with a piano passage or a paragraph I am writing. Happiness, to me, often goes hand in hand with exertion: intense engagement in the creative process, or in learning something, or doing a physical activity. I am not great at yoga or meditation.

However, I do remember a few moments in my life that were defined by a serene stillness and by an overarching feeling of well-being. One was while I was walking across France. I was staying in a château in Alsace-Lorraine. I had just showered and gotten the hiking grit off of me, and I was wearing a feather-light dress I carried to look civilized in town. I was sitting on a chair outside on the lawn, reading a book. There were no mosquitoes. There was no traffic. There were three colors: the weathered gray stone facade of the building, a blue sky, and the green grass. I felt suspended there in time and safe space, where nothing could go wrong. I wish I remembered what I had been reading.

Another time, on a beach in New Zealand’s Abel Tasman National Park, we had stopped for lunch and I collected some mussels off a rock, cooked them in diluted sea water mixed with lemonade, and ate them. Afterward, I sat on the beach watching the waves and I wanted time to simply stop.

A French château, and a New Zealand beach…. And now, here in the hospital, I had a few hours like that, too. Sort of wandering in and out of a light sleep, awakening and feeling at peace and safe and easy. I was grateful to find that feeling in that place and situation. Grateful for the serious, calm care from the nurses and from the food service manager and from the housekeeper. And grateful to my surgeon, especially when he agreed I did not need to spend the night.

So I called David and he drove an hour-and-a-half back to the hospital and learned, no he could not come in and use the restroom, and we turned around and he brought me an hour-and-a-half back home, where he went to the bathroom and I went to bed — where I lay, feeling like someone punched me in the throat and pondering the weirdness of life and how it unfolds and goes on, normally and abnormally and new-normally. And how astonishing it is that we adapt and function, and work, and that the vast majority of us find ways to be kind and loving and creative and helpful and support each other. And I considered the idea of what had to happen in the world for me to put the words gratitude and surgery and pandemic into the same sentence. And then I thought perhaps it was simpler than that: that I should be grateful for gratitude, and for being able to add this snapshot to the album we are all creating of this unpredictable, unnerving, and unprecedented journey we share.

Featured image: Shutterstock

Life with Cancer: “Welcome to a New World”

On the afternoon Tom was diagnosed, we filled out forms as we sat side by side in a waiting area at Mount Sinai Hospital in Manhattan. One series of questions began, “Before you had cancer …”

We looked to one another, surprised by the bluntness of the questionnaire. He had just found the lump on his neck the week before. His ENT ordered an MRI right away, and then we were referred to Mount Sinai.

The cheerful nurse who’d greeted us for that MRI did not have a poker face. When she brought him back to me in that tiny waiting room, her demeanor had changed: No more cheer, she was all business. I knew she’d seen something bad, but I said nothing.

No one had said the “C” word yet, but there it was, spelled out in black and white on that questionnaire. Our shared dark humor intact, I said, “Nice bedside manner.”

Grim as it was, the news was not completely unexpected. He had been reckless with his health. He drank excessively, defending it as “legal” following drug addiction in his youth before I knew him. He boasted about heavy drinking as if it were a sophisticated and manly character trait. Everyone knew he had a problem. I didn’t understand how complicated it was. I didn’t understand any of that at the time.

I saw my seemingly healthier father drop dead from a heart attack when he was only 50. Tom was 56. I’d feared he would have a heart attack, too. I did not expect cancer.

No one had said the “C” word yet, but there it was, spelled out in black and white.

Once we completed the forms, Tom took the clipboard to a lady behind a desk. He said he hoped she was the correct person to hand it to, as this was his first time there. She gave him a world-weary look and, like Selma Diamond, she deadpanned, “Welcome to a new world.” Was she ever right.

The oncologist performed a needle biopsy that immediately confirmed the lump was malignant. His plan of action: Surgery, then radiation and possibly chemo.

The oncologist left us alone in the examination room to take it in, no hurry to leave. “I’m sorry I got cancer,” Tom said.

We looked to one another in silence. Then I said, “Let’s go to Le Cirque,” and he smiled. Le Cirque was our special-occasion restaurant in the city, and this was a momentous day. We enjoyed a spectacular dinner, and we did not speak of hospitals or cancer or anything but the chef’s artistry and how much we delighted in one another. We were alive and we were in this together.

Over the next three years, we spent long hours, days, and nights at Mount Sinai, and I managed preauthorizations, appointments, and billing. We got to know every curtained nook and cranny, every elevator bank in every wing, and the depths of endless color-coded corridors in the basement where radiation equipment is tucked away.

We explored the excellent video catalogue and watched inappropriate House marathons within earshot of other patients during his weekly 5-hour chemo infusions. One night following major surgery and after several days in ICU, we shared a “step-down” room with patients who were in their final days.

“You have two weeks,” a doctor said point-blank to beautifully coiffed Marianne.

“No comment,” she replied, and she spent the rest of the afternoon making cheerful telephone calls. She was alone, but large floral arrangements lined the windowsill beside her bed. Marianne made no mention of her latest prognosis as she chatted with friends on the phone. She did not say goodbye.

Tom had a vision of death when he was wheeled into that room past another patient, Ben. Ben was gaunt and gray. Tom claimed he saw a gaping hole in his throat. I’m not certain that was real. Ben was also alone.

Tom put on a show joking with nurses, his usual public persona. A nurse delivered a note. It was from Ben. “I will never speak again, but I thank you for your humor.”

“A smoker,” Tom whispered to me. “I don’t think he has a tongue.”

From beds separated by a curtain, he and Ben beeped the handheld buttons given to them to self-administer pain relief. They beeped back and forth, responding to one another as if in a comedy routine, each pressing his beeper in varying rhythms, an inside joke as if that could bring more morphine than they were due.

I slept off and on next to his bed that night in an extendable chair several nurses and I appropriated from another room. The next morning, he looked at me gravely and said, “Get me out of here or I’m going to die.”

I found an expensive hotel wing they don’t mention that overlooks Central Park. I gave the hospital a credit card, and off we went. I ran alongside the gurney as he was whisked a full city block inside the hospital away from that sad place. May God bless Marianne and may God bless Ben, but Tom wasn’t ready to be there.

Through those years, as soon as his treatments were completed, whenever we could, we bolted from Manhattan and barreled up the Taconic Parkway to the country house in the Hudson Valley, away from all that. We were determined not to stop living as long as we could, and we held up well. As long as he would.

Lindsay Brice is a photographer and actor. Tom was a writer. He died in 2012.

This article is featured in the January/February 2020 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Featured image: Shutterstock

Miracle Seeker

I was not raised Catholic. I can’t recite the Holy Rosary. And I certainly don’t have what it takes to be considered a devout anything—unless knowing the dialogue to all six seasons of Sex and the City counts for something. But I’m not exactly an atheist either. I’ve always felt a strong sense of devotion to a higher entity. Yet at a dinner party recently when I spoke excitedly about my upcoming trip to Lourdes, the holy shrine in the South of France, I was quickly cut short.

“But you’re not religious,” said a female acquaintance. Her remark spilled across the tablecloth like a tipped-over glass of red wine.

“I used to go to church every Sunday,” I said, somewhat defensively. “And I went to Christian youth camp one summer.”

I went on to explain that Lourdes gets more than six million visitors each year, and I highly doubted every single person who visited the famous grotto of Massabielle was a staunch Catholic.

But who was I trying to convince, her or me?

True, her verbal stoning made me momentarily doubt my bonafides as a miracle seeker. But though not a devout Catholic, I had a good reason for the pilgrimage; being diagnosed with malignant melanoma at age 50 was reason enough. My cancer is what clinicians call Stage IIIB. Look it up. Words like “prognosis somewhat poor” and “very little chance” leap off the screen. Still, my decision to make the trek had been built on monumental hope. For months I had been imagining myself there, miraculously saved. In the end, I took this woman’s ugly remark as one of the many disconcerting side effects of having cancer and handled it the way I do with doctors’ sad faces and negative statistics—I ignored it.

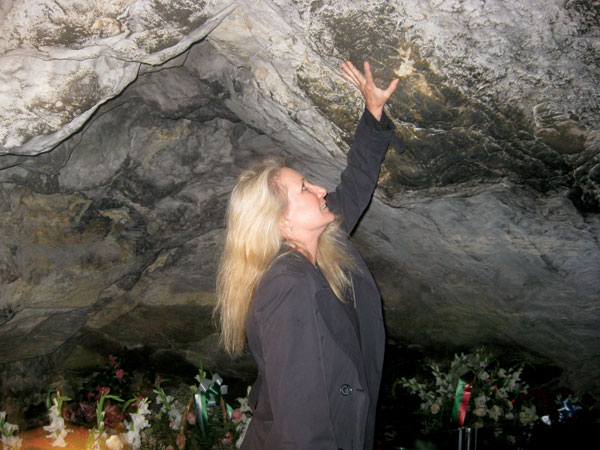

I am running alongside track 19 through the Montparnasse train station toward the silvery vessel that will transport me from Paris to the Pyrenees to the place I’d been dreaming of since I was 15 when I watched the film classic The Song of Bernadette. The thought of standing at the grotto where a young peasant girl, Bernadette Soubirous, saw the Virgin Mary appear 18 times in the year 1858 makes me euphoric.

I have less than two minutes to find the designated rail car stamped on my ticket. It seems a never-ending distance. Traveling too fast, my suitcase tilts on its rickety wheels and falls over.

“S***!” I scream. As I collect my bloated baggage sprawled across the pavement, a nun crosses my path. Uh oh, I think. She’ll probably send up word on high that there’s a foul-mouthed American woman on the way. That won’t bode well for my chances for the “miracle” list. Boarding the train, I notice a sickly bald lady who looks as though she’s undergone intense chemotherapy treatments. Near her is an extremely frail teen boy in a wheelchair reading a French translation of The Hunger Games. Both of these angelic souls seem more worthy of a miracle than I. I’m certain neither of them has ever cussed in front of a nun.

Looking at me, you’d never know my plight. People say I look “fantastic” six months after undergoing two major surgeries. The first excised the tumor on my upper left arm and removed two sentinel lymph nodes to determine if the cancer had spread. The cancerous culprits indeed had set up camp in the first node. And my physician, the world-renowned Donald L. Morton of the John Wayne Cancer Institute in Santa Monica, California, next recommended removal of my axillary lymph nodes (which form a sort of chain from the underarm to the collarbone) despite the painful side effects such as permanent nerve damage and the potential threat of lymphedema, or swelling.

“You don’t have to have chemo?” some people question. “No radiation?”

“Nope.”

“Wow, that’s great,” they say.

I guess that the thought that I won’t lose my long, blonde locks and shrink down to a skeletal frame or puke uncontrollably while sporting a headscarf is an upside. The downside is that there is no treatment or cure for this stage of melanoma—only more cutting should a new cancer emerge. My job is to be vigilant should I note anything suspicious, then to hightail it into the office for further study. This is, quite frankly, terrifying. No neon sign points to the location of a fresh melanoma. My doctor says that the next one will most likely not sprout directly on my skin, but just under it, so I’m supposed to gently rub my (numb) five-inch scar where the first growth emerged, feeling for a new invasion.

The chance of recurrence is quite high. In fact, when you’re Stage IIIB, it’s not a matter of if, but when. So every six months I undergo PET scans or chest X-rays to detect if the cancer has progressed to the dreaded Stage IV. I call it the “mean test.”

They tell me my five-year survival chances are 60 percent.

Melanoma—a cancer of the skin primarily caused by sunlight —is often confused with curable basal cell and squamous-cell skin cancers. But melanoma is the eighth most common malignancy in the U.S., and its frequency is rising faster than any other human cancer. In the 1930s the survival rate for this disease was extremely low; now 5- and 10-year survival rates of Stage I melanoma are well over 80 percent on average. But there are different forms, stages, and classifications that each have different prognoses.

I have nodular type, which is the most aggressive. Even when I discovered an abnormally large mole that quadrupled in size in less than three months, both the nurse and a dermatologist I initially visited assured me it was “nothing.” I sensed that they were both wrong and demanded its removal and biopsy. A case like mine—where skin cancers masquerade as something normal—is a perfect example of why people should get checked regularly. Don’t let your best friend, partner, neighbor, or even your family doctor discourage you from seeking expert attention. Had I listened to my healthcare team, I may have left that HMO allowing my already aggressive cancer to flourish, and I would not be writing this today.

Living with cancer is a learning experience. Part of that learning is to avoid the many misconceptions. Everyone knows somebody who has, or has had, cancer. They are quick to offer medical, herbal, even spiritual advice as well as clinical trial information. Truly, I am touched whenever someone offers any hope they feel may erase my diagnosis. But if I hear one more person tell me the story of their Aunt Jean who had skin cancer for four years and now is totally fine, I’ll lose it. (No offense Aunt Jean.) All melanomas are not alike.

“Is this your first time at Lourdes?”

I look up at a frail-looking pilgrim just beside me in the line for the sacred grotto.

“Yes,” I say.

The woman’s name is Selam. She has come from Vancouver, Canada, but originally hails from Ethiopia. She is 40 years old. Within seconds we are swapping war stories.

“Melanoma, Stage III,” I say.

“Colon cancer … I’ve been given six months to live,” she whispers.

I let her step in front of me and study how she grazes the grayish stone that leads to the niche with her left hand, stopping every few feet to kiss the rock. A white rosary entwined in her right hand swings gently from side to side.

I begin to copy her every move. If she makes the sign of the cross, I do, too. If she pats the water droplets that trickle from the cave-like surface and touches her face, I do the same. It is as if she’s been sent to me as a personal guide. Nearing the sacred spot, she begins to weep. I stroke her back the way a mother would soothe a child with a skinned knee.

She kneels before the statue of Mary resting high in an alcove. Dabbing moisture from the stone, my hand presses the gash on my upper left arm, but I forget to ask Mary for anything because of a deep concern for my new companion. Selam’s despairing sobs grow louder—agonizing wails echoing in an already hushed enclave.

Minutes later, she rises and turns toward me.

I open my arms wide and she collapses against me. We hold each other in a long embrace as though lifelong friends.

“I want you to have this,” I say, reaching into my bag for a vintage religious medal of Bernadette that a dear friend sent with me for luck. “Pin it over your heart. It will protect you.”

“Oh, thank you, my love,” she says. “I prayed I would meet someone here.”

Who knew my presence alone would answer a dying woman’s prayers? Fear of what I lacked spiritually had been eating away at me in the days leading up to this moment. But her words are like a salve.

As the two of us walk arm in arm, we sing aloud, butchering the lyrics to “Ave Maria,” giggling in between verses. We pass thousands of invalids, some on gurneys and many in wheelchairs, most assisted by unpaid hospitallers—volunteers who look like a combination of nun and nurse. I have a sudden, unexpected calling to be one of them.

Selam tries to disguise the immense pain she is suffering and insists on our sitting together for hours at a sidewalk cafe, wiling away the afternoon sharing our hopes, fears, and her desire to find one last love. As we sit and talk, any need to justify the depth of my religious belief seems to vanish.

I had arrived alone at the holy shrine, a restless soul beside those green fields, and rather than glimpse the image of the Virgin Mary I had my own singular and singularly valuable divine visitation. Melanoma had brought me to Lourdes and given me Selam, the woman whose name means “peace.”

Three days later, fighting back tears and promising we’d meet again, she gives me a final gift: a pocket Holy Rosary booklet complete with tiny red beads and crucifix.

“See? Now you never need worry,” she says sweetly. “You’ll always have the right words.”

Six months later, after a chest X-ray, I am classified as disease-free. I harbor much hope, but there is always my next scan. Upon returning from Europe, I would speak with Selam twice. Her cancer had rapidly spread, and she was bravely undergoing extreme bouts of experimental chemotherapy. Her last words to me were, “I’ll call you next week, my love.” That was several months ago.

Just recently I have signed up with Our Lady of Lourdes Hospitality North American Volunteers to become one of the thousands of companion caregivers that Selam and I had seen. Some of the pilgrims will understand English, and some will not. Yet I’m not too concerned about the language barrier. Selam showed me that faith does not require proficient verbal skills.

If she were here with me now I’d say, “Can you imagine? Me? Speaking French? Might as well be Swahili!”

She’d just smile and make the sign of the cross.

The Post Investigates: Cancer Vaccines

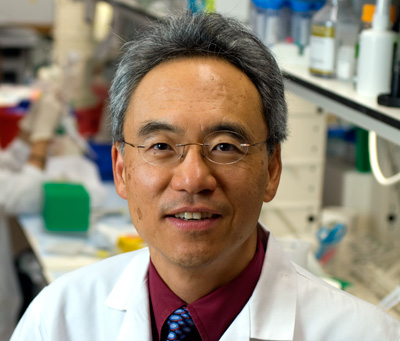

Cancer researcher Patrick Hwu, M.D., likes to think of the body’s immune system as the armed forces in charge of homeland defense and of tumor cells as homegrown terrorists. When everything is going well, the immune system recognizes malignant cells and destroys them. But like a general whose troops are not quite the crack soldiers he expected, Dr. Hwu has to admit, the terrorists too often get the better of his wimpy forces, which is why 560,000 Americans will die of cancer in 2009, the American Cancer Society forecasts. “We don’t really know why the immune system doesn’t keep most cancers in check,” says Dr. Hwu, a cancer immunologist at the M.D. Anderson Cancer Center in Houston. “The tumor might disguise itself from the immune system or make things that suppress the immune system.”

When he was working at the National Cancer Institute (NCI) in the 1990s, Dr. Hwu and colleagues decided they needed an innovative way to retrain the immune system. What if they could inject into cancer patients the very “markers” that stud the surface of malignant cells? That’s how vaccines for infectious diseases such as measles and smallpox work, by training the immune system to recognize and attack the markers on disease-causing viruses. In this case, Dr. Hwu and others reasoned that injecting “tumor antigens” might train the immune system to recognize the tumor cells as foreign and destroy them. It would be a “cancer vaccine” — not a vaccine like that for measles, which prevents a disease, but one that treats it. (These cutting-edge cancer vaccines are not to be confused with Gardasil, a vaccine that primes the immune system to attack the virus that causes cervical cancer. Very few human cancers are known to be caused by viruses, so “cancer vaccine” has come to mean one that treats existing cancer.)

The NCI scientists were hardly alone in dreaming of a cancer vaccine. The appeal was obvious: Oncologists’ cancer-fighting arsenal consisted of surgery, radiation, and chemotherapy — or as critics like to say, cutting, burning, and poisoning. Not only did the three weapons come with serious side effects, but they were far from universally effective. Perhaps harnessing the immune system would vanquish tumor cells with little to no collateral damage to the rest of the body. The idea took hold in a serious way in the 1970s, recalls Dr. Len Lichtenfeld of the American Cancer Society, “and it was going to be a slam dunk. We were going to cure cancer.” Obviously, that did not happen. Instead, vaccine after vaccine failed. But with advances in their understanding of both cancer and immunology, scientists finally scored some notable successes: Three large-scale studies, called Phase III clinical trials, presented at the 2009 meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO), suggest that cancer vaccines may one day play a role in cancer treatment.

In one study, a vaccine based on the work of Dr. Hwu and his NCI colleagues extended what’s called progression-free survival — how long patients live before a cancer that has been treated with chemotherapy or radiation returns — in people with advanced melanoma, one of the most lethal cancers. The vaccine consists of antigens that stud melanoma cells. By injecting these “gp100” molecules into patients, “the vaccine activates the T cells of the immune system to recognize the antigens on the surface of the tumor,” says Dr. Hwu. “The T cells then secrete enzymes that poke holes in the tumor cells’ membrane, causing it to disintegrate” and the cancer cells to die.

This was the first time a melanoma vaccine had shown any benefit in a Phase III trial, but even with this distinction, it was no “slam dunk.” The 93 patients who received a standard therapy called interleukin-2 and no vaccine remained in remission for an average of 1.6 months. The 86 patients who received the vaccine plus interleukin-2 remained in remission for just under three months; hardly a big improvement. And on what every cancer patient cares about most — staying alive — the vaccine fell short. Vaccinated patients lived 17.6 months, on average, while unvaccinated patients lived 12.8 months, a difference that statistical analysis determined could be due to chance.

Why wasn’t the benefit greater? It’s possible that the patients did not have enough T cells to mount an effective immune response, says Dr. Hwu. Or maybe, for some reason, the T cells do not find the melanoma cells. Perhaps the tumor disguised itself, hiding the antigen that the T cells were trained to look for. “It’s possible that we did not have enough soldiers, or that they were not well-enough trained, or that they were not able to find the battlefield,” says Dr. Hwu. It’s also possible that a vaccine needs to contain more than the gp100 antigen. “Unique antigens specific to a patient’s cancer do exist, and using them might stimulate a more effective immune response,” he says. “But it would take months to synthesize such a custom-made vaccine,” and advanced melanoma patients do not have months.

Another study unveiled at ASCO this year, however, took the customization approach. Invented by M.D. Anderson’s Larry Kwak when he, too, was at NCI, the vaccine contains markers from each patient’s cancer — in this case, a form of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma called follicular lymphoma, which is a cancer of (ironically) immune-system cells called B cells. After a biopsy harvests a patient’s malignant B cells from the lymph nodes, it takes about one month to make the vaccine. “The vaccine uniquely recruits the patient’s immune system to seek and destroy only tumor B cells,” said Stephen Schuster of the University of Pennsylvania, who led the study.

“It’s the ultimate in personalized therapy,” adds Dr. Kwak. “Even if patients have the same type of lymphoma, the tumors will still have different antigens, and that’s what you want your vaccine to contain.” The 76 patients who received the custom-made vaccine after a standard course of chemo remained disease-free just over one year longer than the 41 patients who received the chemo alone (44.2 months compared to 30.6 months). In an earlier Phase II study at NCI, patients have remained disease-free for an average of eight years.

Crucially, all the patients in the latest study were in complete remission or had no detectable cancer when they received their personalized vaccine. That is, they had responded to standard chemo and sustained a remission for six months. To skeptics, that raises the possibility that these patients’ cancer might have been less aggressive, and that fact — not the vaccine — accounts for their longer survival. In addition, the vaccine was compared to chemo that has now been superseded by something more effective. Oncologist Ron Levy of Stanford University, a founding father of cancer vaccines, gives BioVax ID “a qualified yes” in terms of effectiveness, but only a “maybe” on whether it will find a meaningful role in treating patients with follicular lymphoma.

Dr. Kwak sees it differently. He admits that the vaccine — and possibly all cancer vaccines — work best in patients whose tumor has shrunk to almost nothing or who are in complete remission. “Then you bring in the vaccine to mop up any remaining cancer cells,” he says. “That’s the strategy, and it should work for other cancers.” If he’s right, then the failures of other cancer vaccines might be because the patients in those studies had active and sometimes widespread cancer. “We now suspect that cancer vaccines will not work very well against advanced tumors,” says Dr. Kwak. “Tumors have the ability to turn off the immune response, and the more tumor you have, the more factors that can do that.”

That may explain why a vaccine for prostate cancer has fallen short. Called Provenge, it failed to beat back disease, let alone improve survival, in early tests, and the Food and Drug Administration refused to approve it in 2007. But the manufacturer, Dendreon, has spent an estimated $560 million on it and isn’t giving up. In a new trial, also presented at ASCO this year, the company announced that among men whose prostate cancer was no longer responding to hormone treatment or chemo, those who received Provenge lived four months longer than those who did not, 26 months versus 22 months. Just under one-third of the Provenge men were still alive after three years, compared to just under one-quarter of the men who did not receive the vaccine — 31 percent versus 23 percent. That’s far from a cure, but Dendreon is hopeful that it will get a green light from the FDA in 2010.

But don’t expect that to open the floodgates for cancer vaccines. So many have failed that it seemed as if they were going to be yet another therapy that looked terrific on paper, and even in lab animals, but which crashed and burned when tested in people. For instance, in 2006 a pancreatic-cancer vaccine called PANVAC-VF failed to improve overall survival. Considering that it was being compared to chemotherapy that keeps patients alive for a median three months, the result was a big disappointment.

The encouraging results for the melanoma and follicular lymphoma vaccines — and, to a lesser extent, for Provenge — have definitely been heard, breathing new life into a field that had been hanging by a thread. “Looking to the future, I think we’ll see a role for vaccines where the cancer is found very early, when the disease burden is small [because the patient is in remission], or when there are circulating cancer cells that can’t be eliminated any other way,” says Dr. Lichtenfeld. “But it looks unlikely that cancer vaccines will produce a response in people who have cancer throughout their system.” The latter, of course, are the sickest of the sick, so there is no small irony in the likelihood that this most innovative of cancer treatments will help not those who need it most, but those with an already hopeful prognosis.