Terry and the Pirates: Adventure Comics for Grown-Ups

When war came to the U.S. in 1941, cartoonists began to work references to the conflict into their strips.

Milt Caniff’s Terry and the Pirates was the exception. The two main characters in his action-adventure series had been fighting the Japanese invasion of China for years.

The comic strip began in 1934, when protagonists Terry Lee and Pat Ryan began their travels in China. They were soon attacked by river pirates, led by the exotic Chinese “Dragon Lady.” She was the first of several gorgeous female characters who would appear in Caniff’s works. The erotic appeal of these cartoon women was a major reason the comic strip enjoyed a large, devoted following among American GIs.

Caniff’s comics were notable for their unique artistry and realistic plotting. He had a high-contrast style with little shading and a talent for using shadow for dramatic effect. And no one came close to matching Caniff’s combination of realism, romance, action, and character.

The story line included characters and events of the war in China with the two heroes working with the Chinese military to fight the Japanese forces. The stories could be quite involved, and characters were often nearly squeezed out of a frame by the long speech bubbles over their heads. Curiously, Caniff’s cartoon syndicate prohibited him from identifying the enemy as Japanese, so, in the comic strip, they were only referred to as “the invaders.”

Caniff benefitted from Americans’ growing interests in the war in China and their assumption that Caniff was a veteran traveler to that country. But as Collie Small points out in “Strip Teaser in Black and White,” the artist had never set foot in China. His knowledge of the Far East was drawn entirely from reference books.

It made little difference to his fans, Small adds. In 1946, Terry and the Pirates was read by 25 million people.

In his article, Small tells why Caniff ran two separate stories: A Sunday series that was safe for the kids and an “adult” story line during the week. He also tells why the artist always drew the last panel in a comic strip first.

Strip Teaser in Black and White

By Collie Small

Originally published August 10, 1946

There’s nothing funny about Milton Caniff’s Terry and the Pirates — except possibly the reactions of its followers. Some want to murder Caniff. Some would just burn his brushes.

As a prominent wholesaler of Oriental skulduggery and a brand of sturdy Saxon virtue that can usually be counted on for a last-minute triumph over the forces of evil, Milton Caniff is fairly well conditioned to the reflexes of the 25,000,000 people who read his comic strip, Terry and the Pirates. Since 1934, when Terry Lee made his debut as a rosy-cheeked young adventurer wandering through China in search of a hidden mine, Caniff has been selling his dizzy distractions with spectacular results.

This high success has continued unabated throughout the 12 years, and appears to be due largely to Caniff’s flair for provoking hysterical responses from his reader critics, who exhibit an enthusiastic capacity for becoming unstrung by Terry’s hair-raising skirmishes with Destiny.

In giving vent to their troubled allegiance, they have called Caniff a murderer and have invited him to be the party of the first part at a public hanging. One petulant reader, emotionally askew over Terry’s talent for becoming involved in nerve-racking situations, accused Caniff of abusing his responsibilities as a cartoonist by eating pie late at night and transferring his indigestion to the drawing board.

An irascible resident of Yorkville, New York’s German colony, once threatened in no uncertain terms to burn Caniff’s brushes because he dared to show a monocled German officer consorting with a Japanese officer before the war. Later, the Family Journal, a Copenhagen newspaper carrying one of the numerous foreign editions of Terry and the Pirates, was dynamited out of business by thin-skinned Quislings vexed by Caniff’s depicting a German, a Jap and an Italian in a state of un-Axis-like terror following the bang of a firecracker.

Caniff accepts such verdicts as inevitable, feeling that when a reader buys a newspaper, he also buys the privilege to complain. He does not feel, however, that dissatisfied readers should succumb to sudden fits of pique and go around blowing up such lucrative sources of revenue as the Copenhagen Family Journal. Nor does he feel that excitable readers should further unnerve him by dispatching frantic telegrams of warning whenever one of his characters appears headed for trouble.

Caniff frequently is just as nonplused over how to extricate his hero from complicated situations as the most impatient reader, and the latter would be horrified if he knew how often Caniff is tempted to let the hero expire in his tracks and thus be done with the whole business.

In 1941 Caniff precipitated a national incident by permitting one of his characters the almost unheard-of comic-strip prerogative of dying. The victim in this case was one Raven Sherman, an American heiress for whom Caniff had won unusual sympathy by portraying her as an undaunted and high-hearted young lady overcoming all obstacles to aid the Chinese in resisting what Caniff, at the time, was calling the Japanese “invader.” Miss Sherman was rudely pushed off a truck, and subsequently died of her injuries. She was buried on a lonely Chinese hillside in a ceremony so moving that millions of funny-paper disciples were plunged into their own peculiar kind of melancholia. Flowers poured into the offices of the Chicago Tribune-New York News Syndicate, which distributes Terry and the Pirates, and several hundred college students in the Midwest felt constrained to bare their heads and turn toward the east in a last reverent gesture. There were other manifestations of general hysteria, and old-timers at the business of gauging public reaction announced it was the worst blow that funny-paper readers had suffered since the death of Mary Gold in the Gumps many years previously.

With luck, Raven might be around today, since Caniff had not always planned to get rid of her. But as he says now, with a faint trace of ghoulishness, “I decided it was time to let somebody die.”

Caniff not only killed Miss Sherman in cold syndicated blood, but he duped his readers while he arranged her death. Originally, Raven had not been a very pretty girl, and for months Caniff had worked to prepare her for her ultimate demise, gradually softening her sharp chin and redoing her hair. By the time she finally died, Raven was exactly as beautiful as sacrificial heroines are supposed to be, and only a handful of readers suspected what Caniff had been doing to them.

Caniff graduated to Terry and the Pirates from The Gay Thirties and Dickie Dare, two strips he did for the Associated Press after being lured to New York from the Columbus, Ohio, Dispatch. Born in Hillsboro, Ohio, in 1907, the son of a printer, Caniff spent most of his life in his native state before coming to New York, attending Ohio State University and serving his apprenticeship in the art departments of various Ohio newspapers. At Ohio State, he contracted the acting bug, a disease from which he has never entirely recovered. But Billy Ireland, the famous Dispatch cartoonist, rescued Caniff by convincing him that cartoonists, generally speaking, averaged more meals per day than actors.

In 1934 the late Joseph Medill Patterson, publisher of the New York Daily News, discovered himself chuckling at The Gay Thirties, and immediately summoned Caniff to 42nd Street. Patterson told Caniff to submit an adventure strip based on Patterson’s blood, thunder and intrigue-in-the-Orient formula, plus a list of tentative titles. Caniff happily produced both in record time and the strip met with Patterson’s immediate approval. Among others, Caniff had suggested “Terry” for a title. Patterson circled the name and penciled after it: “and the Pirates.” Caniff wisely accepted the suggestion and went on to name the central character Terry Lee because he happened to be reading a biography of Robert E. Lee at the time. The young cartoonist, then only 27, launched his guardianship of Terry at the comparatively modest salary of $100 a week — a figure which has never been changed, although Caniff has boosted his total income to around $80,000 a year by way of taking a substantial slice of the profits. This does not include what he makes from books, movies, novelties and other byproducts.

Terry and the Pirates is neither the largest nor the funniest of current comic strips. Blondie and Li’l Abner, which are Caniff’s favorite strips, both have wider circulation and presumably wider appeal. So does Dick Tracy, which Caniff professes to like best of the suspense strips. In a general-popularity poll, Terry is likely to come dragging in sixth or seventh, mostly because Caniff does not make enough concessions to children. On Sunday, which is children’s day in the comic section, he avoids love and kisses to spare parents the pain of having to explain to the children. But the rest of the week Caniff draws exclusively for the older reader.

Caniff has never tried to be funny in Terry and the Pirates, an adventure serial drawn according to a formula closely resembling the technique used in motion pictures. He exercises loving care with his dialogue. The writing in an adventure strip is considerably more important than the drawing for sustaining reader interest day after day, and, as Caniff says, “It’s getting the reader to buy tomorrow’s paper that worries me. He’s already got today’s.”

Although the dialogue in Terry is as polished as any comic-strip dialogue is likely to be for some time, Caniff’s preeminence in the field of cartooning is probably due equally to his draftsmanship, his eye for detail and his brooding concern for accuracy. His library is filled with such diversified stores of information as The Complete Book of the Occult and Fortune Telling and The Book of Pottery and Porcelain. Caniff subscribes to some 60 periodicals, including the Infantry Journal when there is a war around, and he has been known to spend a full day in the Smithsonian Institution, stalking a rare fish he wished to reproduce.

Because the action in Terry and the Pirates was set principally in China, readers assumed Caniff had traveled extensively in the Far East. Actually, Caniff has been no closer to China than Ruby Foo’s restaurant in New York, but he can produce from his bulging files a set of Chinese license plates, innumerable laundry tickets, a picture of a genuine pirate queen and a wine list from Shanghai’s plush Mandarin Club. He can also discourse at impressive length on such topics as plane crashes, harbors, cow hands and the interiors of wealthy homes. He is known, by the Chicago Tribune, at least, as an “armchair Marco Polo.”

In beginning a new sequence in Terry, Caniff may consult as many as 40 reference books. Like most mortals, he is not infallible, but he seldom errs. When Terry was learning to fly, Caniff consulted Col. Phil Cochran, whom he had known slightly when both were undergraduates at Ohio State and who later became his close friend and model for the Air Forces colonel, Flip Corkin. Cochran wrote Caniff a laborious 22-page letter in longhand, warning Caniff of the pitfalls Terry might encounter in learning to fly. Terry had his troubles, but his mistakes were honest ones that Cochran himself had made.

When Caniff does make a mistake, it is likely to be a monumental one. He once described Hong Kong as an American naval base, and had the greater misfortune to have a number of vital characters languishing in Hong Kong when the crown colony fell to the Japanese. In drawing a street in Boston, with the old State House in the background, Caniff put a car in the street to show movement, reminding himself at the time that it was almost sure to be a one-way street and that the car would be going the wrong way. He was right. It was.

The worst miscalculation to bedevil Caniff concerned his strip character, Burma, the delectable American handmaiden of a Chinese pirate ring. Burma gave up piracy to befriend our side when war broke out in the Pacific. But she is now listed as missing because Caniff grievously misplaced her on an out-of-the-way island. To date, Caniff has not been able to retrieve her, and if Burma needs advice, she would do well to settle down and be comfortable because Caniff still has not figured out how to rescue her, although he may send searching parties out next fall.

Some readers, who came in late at a time when Burma was doing her level best to be patriotic, were unaware that she previously had been a very prickly thorn in the side of Caniff’s British characters, who were constantly trying to arrest her as an accomplice of the pirates. The readers who didn’t understand the British attitude continually wrote Caniff to inquire why Burma was in such bad odor with our Allies. Finally, Caniff wrote Lord Louis Mountbatten, who was in charge of things in Southeast Asia, and asked for an official pardon for Burma. Caniff pointed out that the United States Army had been nice enough to give Terry Lee a genuine serial number when he was promoted to second lieutenant. Mountbatten, unimpressed, balked at writing an actual pardon, but he did say it would be all right for Caniff to say he had pardoned her. Caniff stubbornly refused to settle for anything less than His Majesty’s complete exoneration of Burma. So, when she disappeared, Burma was still out of favor with the British, although everyone else was pretty much on her side.

Caniff originally disliked drawing women. When the voluptuous Dragon Lady suddenly appeared in startling contrast to his comic-strip ladies, most of whom seemed to be constructed principally of pipe cleaners, a newspaper editor sent Caniff a telegram.

“Thought you disliked drawing women,” the editor said.

“Did not draw women years ago because did not know how,” Caniff replied. “Have been around some since.”

John Steinbeck, the author, was so struck with the Dragon Lady’s beauty, that he told Caniff she had “warmed old bones and breathed on gray embers.” Steinbeck also confessed that he had been doing what a lot of other people had been doing — arguing about the Dragon Lady’s virtue. Mr. Steinbeck was thrashing the thing out with his brother-in-law, whom he described as a “romantic of the junior-prom school.” His brother-in-law, Mr. Steinbeck said, dreamed secretly of domesticating the Dragon Lady and installing her in “one of those stucco duplexes with a two-family lawn.”

“He was a fool,” Mr. Steinbeck concluded.

Another prominent devotee of the Terry strip is Clare Boothe Luce, who once confessed to Caniff: “You are the only man I ever wrote a fan letter.” Among the better-known nonreaders of Terry are Pearl Buck, who has her own troubles with China, and Mrs. Caniff. Mrs. Caniff doesn’t like comic strips, including Terry and the Pirates, and makes no bones about it. Unfortunately, however, she is constantly beset by curious friends who seem to think she can give them a teeny-weeny hint of what is coming next. For such emergencies Mrs. Caniff has a ready-made answer.

“Oh, I couldn’t possibly give away any of Milton’s trade secrets,” she says, just as though she knew any.

Although he draws with a classic draftsmanship unmatched by any other cartoonist, by their admission, Caniff has no pretensions concerning his contribution to the world of art. The Egyptian Book of the Dead and the codices of the Mayan temples also used strips as a device for indicating action, and since then there have been enough experts around so that Caniff is inclined to consider himself simply another in a long line of artists drawing from left to right. Although he has studied portrait painting and has had his cartoons hung in the Metropolitan Art Museum and the fashionable Julien Levy Gallery in New York, Caniff belittles these achievements.

“I don’t feel that comic strips contribute very much to the culture of the country,” he says. “But I do feel they are a definite manifestation of folk art, in so far as that can be called a contribution.” Caniff, a hulking, moon-faced Irishman with a high, quick laugh and an impish sense of humor, was once described by an impressionable young-lady writer as “sweet, kinda plump and with big blue eyes.” Actually, he does embody these attributes, but he feels, perhaps justifiably, that the young lady might have found another way of putting it.

Caniff does most of his work in his pajamas, and often goes for days without dressing. He harbors a grudge of long standing against daylight, mostly because of its association with ringing telephones, which distract him, and, as a result, he works almost entirely at night. Among other things, the telephone has forced him to change the pronunciation of his name. Originally, Caniff was pronounced with the accent on the last syllable, but he has changed this to “Can’ iff,” since, in talking over the telephone, strangers invariably ask him to repeat his name if he uses the original pronunciation. His parents, however, who still live in Ohio, have gone right along with no apparent inconvenience and continue to pronounce the family name as the Irish philologists intended. Although he keeps his apartment in New York for whatever emergencies a stranded cartoonist may encounter, Caniff does most of his work in a spacious studio in his home 38 miles up the Hudson from New York.

In addition to his other troubles, Caniff suffers from an occupational disease peculiar to creative artists in that he has occasional illusions that his head has a leak in it somewhere with ideas dribbling out unnoticed and uncaptured. When this happens, he accelerates his reading, and thus replenishes the supply. Caniff barely gets his strips to the syndicate in time for his deadlines, and he misses trains by approximately the same margin he meets deadlines. He is an inveterate train misser, and is famous locally for this idiosyncrasy.

During the winter months, Mrs. Caniff reads aloud to him while he draws. Caniff draws with his left hand and writes with his right, the result of winning a split decision from a grammar-school teacher who was determined to make him a right-hander at a time when he was equally determined to be a southpaw. Since he works with what obviously is the wrong hand, Caniff has to draw the last panel first, a practice presumably requiring considerable mental adjustment.

Because several Terry characters, such as Flip Corkin and Dude Hennick, who, in the strip, was an instructor for Chinese fliers, were adapted from real people, the impression has grown that all of what Caniff calls his “ paper dolls” were taken from real life. Occasionally he does reach out for real people, but most of his characters come straight from the ink bottle. He did use General Chennault as a model, however, calling him only “the general,” and Lord Mountbatten found his way into the strip, although he wasn’t called anything. Hardly anyone was fooled, including Mountbatten, who, finding himself in the same comic strip, wrote Colonel Cochran a letter that began: “Dear Flip.”

A cocky, freckle-faced young character dubbed Hot-Shot Charlie, who flew as a wing man in Terry Lee’s fighter element when they were battling the Japanese in the air, has caused much of the controversy over whether all Caniff’s characters are actually real people. Hot-Shot, who lives only in Caniff’s imagination, has been claimed by dozens of people, most of them freckled pilots who profess to recognize themselves in caricature. Caniff recently brought Hot-Shot home to metropolitan Boston after his tour of duty overseas and deposited him in an apartment house. His fetish for detail prompted him to use the address of a real apartment house and when Hot-Shot prepared to return to China as a copilot on Caniff’s new funny-paper airline, Air Cathay, Mrs. Morris Segal, manager of the building, was nearly swept under by applications for the vacant apartment. The Boston Herald finally came to her rescue by running a front-page story disclosing that the decision to vacate that particular apartment was Mr. Caniff’s, and not Mrs. Segal’s.

During the war, Terry and the Pirates took on a rather alarming significance. Caniff’s predictions were frequently so accurate and well-timed that the FBI dropped in several times for question-and-answer tête-a-têtes. When Caniff anticipated Cochran’s glider invasion of Burma by using his character, Flip Corkin, to intimate something rough was coming up, he was immediately suspected of worming confidential information from Cochran. Actually, Caniff had simply been keeping his eyes and ears open, and had decided that something rough was coming up. Cochran provided no clues at all and, in fact, was so chary of Caniff’s prescience during most of the war that he was afraid to do much more than tip his hat to Caniff.

There were never any attempts to censor Terry and the Pirates. Instead, the Army and Navy compromised by designating Caniff’s studio a war plant because of his advanced ideas about fighting wars and the documents in his files. All visitors, including Caniff’s secretary and the man who delivers the groceries, were required to sign a passbook on arriving and again on leaving.

The war imposed a considerable strain on Caniff’s productive capacity. In addition to keeping Terry going, he toured hospitals, giving drawing exhibitions, and devised 70 new insignia for Air Force and submarine crews. He illustrated a soldier’s handbook on China, and suffered the agony of regular office hours in Washington while he drew posters on the subjects of gas and incendiary bombs, working under two officers improbably named Gasser and Burns.

Probably his biggest chore was a weekly strip called Male Call which he contributed to service newspapers. It featured a handsome young lady named Miss Lace, whose principal problem, Caniff discovered, was steering clear of Army chaplains. Miss Lace, it must be noted, was not entirely successful in this endeavor and the Army rejected several strips, including one long five-panel drawing of Miss Lace lying down. Caniff, who insists he was simply trying to produce a pin-up which could be turned upright, tried three times to make Miss Lace sit up for the Army. But there wasn’t room; she kept sticking her head through the top of the strip. Caniff finally gave up.

When he let Terry emerge into the peacetime world, Caniff was suddenly released from the framework of regulations and protocol which had bound him, and he experienced a short but alarming tendency to flounder in his new liberty.

“I had to reconvert in Macy’s window, and it scared me,” he says.

Caniff currently is struggling with another, more important reconversion job. On October 15, Terry and the Pirates will surrender their destinies to another cartoonist while Caniff begins a new strip for the Field Enterprises. Terry and his other present characters are the property of the Tribune-News Syndicate, and will be entrusted to the skill of another artist when Caniff begins his new strip at a lusty $100,000 a year for five years, plus a substantial share of the profits.

While he continues to draw Terry, Caniff amuses himself by devising complicated situations as suitable notes on which to end his proprietorship of the strip. Although he does not yield often to such fiendish whimsey, Caniff is fascinated by the prospect of his successor’s dipping enthusiastically into his ink bottle for his first Terry strip and suddenly discovering that Caniff has left his principal character in a hopeless situation. Actually, Caniff has no intention of befuddling anyone, and will simply end the particular sequence at a point from where the new artist can pick up the thread.

Caniff’s new strip is still nameless, plotless and completely barren of people — which indicates either that Marshall Field’s faith is boundless or that Caniff’s talent is indisputable, since Field still doesn’t have any idea of what he has bought for $100,000 a year.

The central character of the new strip will be a pilot, who will have served in the war and will have emerged a comparatively young hero. There will be a succession of pretty girls. China will not be the setting for the new strip, although Caniff will use a foreign locale for adventure.

Caniff has no illusions that the new strip will be immediately gobbled up by a Caniff-hungry public. He feels that it will take some time to re-educate his readers. If nothing else, this should give him some respite from the professional favor seekers, who will be hard put to figure out what characters to ask him to draw for their personal albums. There are bound to be, however, some readers who will always stump him.

One of these sent Caniff a picture of himself and his girl, pointing out rather unnecessarily that she had a broken nose. In asking Caniff to draw a pretty likeness of the not-so-pretty girl, the young man showed sublime faith in Caniff.

“I am more than sure you can put a nice nose on her,” he said hopefully.

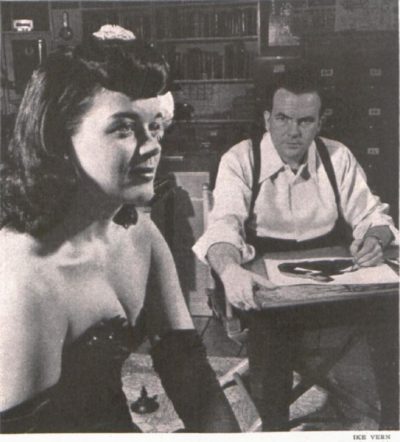

Photos by Ike Vern from the August 10, 1946, issue of The Saturday Evening Post (SEPS)