In a Word: So Many Cardinals

Managing editor and logophile Andy Hollandbeck reveals the sometimes surprising roots of common English words and phrases. Remember: Etymology tells us where a word comes from, but not what it means today.

The word cardinal covers a lot of ground in the English language. We’ve got the cardinal directions, cardinal numbers, the cardinals of the Catholic church, cardinal sins and cardinal virtues, and of course the state bird of Indiana, Illinois, Kentucky, Ohio, Virginia, and West Virginia — not to mention my alma mater’s mascot. Cardinal might be the only word to have found a comfortable home in the lexicon of navigation, mathematics, liturgy, and ornithology. But each of these types of cardinal stems etymologically from a common seed of a word.

Cardo was the Latin word for “hinge” — or more broadly, “a pivot or axis on which something turns.” As ancient discussions turned to the cosmological, cardo took on a broader meaning: “the axis points on which the universe rotates around the Earth,” namely, the Earth’s poles. North and south, then, become the first two cardinal directions (from the adjective cardinalis, “serving as a pivot or hinge”), and the other two, east and west, simply fall at right angles to them.

In the fourth century A.D., that hinge took a metaphorical bent, and we start finding mention in Catholic religious texts of the virtutes cardinales, the cardinal virtues (temperance, prudence, justice, and fortitude). Not only do the four cardinal virtues serve as one’s compass for a moral life, but all other moral virtues hinge on these four. The late sixth century saw the emergence of their opposite, the cardinal sins — now more commonly known as the seven deadly sins.

If cardo means “pivot,” one translation of the adjective cardinalis is “pivotal” — first physically and then, as language evolved, metaphorically. Cardinalis came to mean “essential,” and you can’t get more essential to mathematics than the cardinal numbers (in Medieval Latin, cardinalis numeri), a concept that started appearing in texts in the sixth century. Cardinal numbers are the most basic numbers — one, two, three, and so on (there is some debate about whether zero should be included) — as opposed to ordinal numbers — first, second, third, etc. — which place things in order.

Cardinalis also shifted from “essential” to “chief, principal,” and it’s from this meaning that the Catholic church, using Medieval Latin, named certain “ecclesiastical princes” cardinals. These bishops (episcopi cardinales), priests (presbyteri cardinales), and deacons (diaconi cardinales) were senior church leaders and advisors to the Pope, and the election of a new Pope hinged on them. (Today, it’s very rare for someone to be named a cardinal who isn’t an ordained bishop.)

In French, cardinalis in this ecclesiastical sense became cardinal, and it’s from that source that the word was borrowed into English in the early 12th century — but the story of cardinal doesn’t end there.

When performing liturgical rites, Catholic cardinals commonly wear red, signifying the blood of Christ. The specific color of their frocks was so recognizable — and apparently so consistent — that that shade of red was often referred to as cardinal red. American colonists in the 18th century found a red, crested, North American songbird that seemed clothed in that color. The association was so strong that they named the bird the cardinal.

Featured image: Rizwan Mian / Shutterstock

Movies for the Rest of Us with Bill Newcott: Second to Nun

See all Movies for the Rest of Us.

Featured image: Whoopi Goldberg, Kathy Najimy, Ellen Albertini Dow, Edith Diaz, and Mary Wickes in Sister Act (Touchstone Pictures)

Considering History: Dorothy Day and the True Spirit of Christmas

This series by American studies professor Ben Railton explores the connections between America’s past and present.

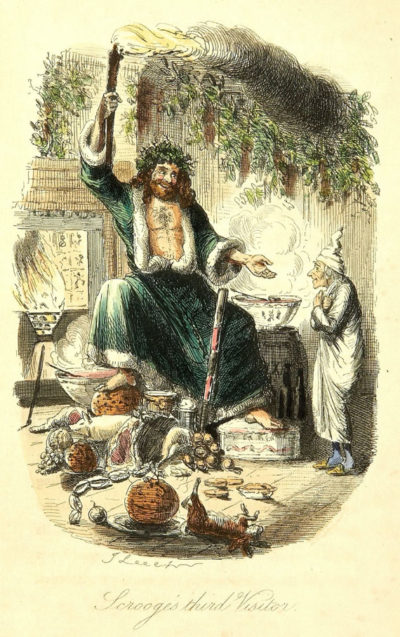

Charles Dickens’ novel A Christmas Carol (1843) is one of the most enduring and popular holiday stories, but its central anti-poverty theme is too often forgotten. Ebenezer Scrooge learns a number of lessons in the course of the novel, but the most poignant and powerful are those he learns from the Cratchit family about the horrors of poverty. As the Ghost of Christmas Present puts it, after quoting Scrooge’s own despicable sentiments about “the surplus population” back at him when it comes to the question of young Tiny Tim’s survival, “It may be, that in the sight of Heaven, you are more worthless and less fit to live than millions like this poor man’s child. Oh God! to hear the Insect on the leaf pronouncing on the too much life among his hungry brothers in the dust!”

This holiday season has seen a renewal of longstanding American debates over whether and how to collectively, publicly celebrate Christmas. In many ways those debates represent a constructed distraction, an attempt to divide Americans over issues that are not in fact in dispute (we are and have always been free to celebrate whatever holidays we choose in whatever manner we’d like). But if we take to heart the lessons of Dickens’ holiday tale, we can use them during this season to celebrate an American whose life exemplifies the true spirit of Christmas: Dorothy Day.

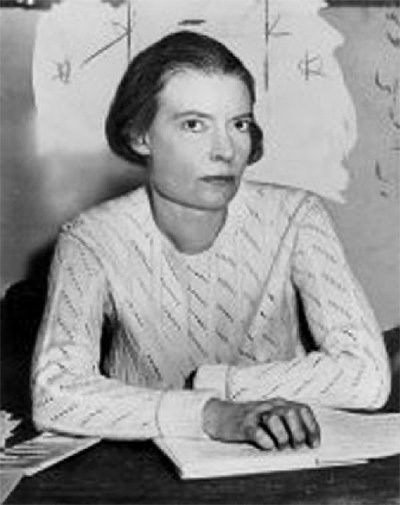

Born in Brooklyn and raised in Oakland and Chicago, Day (1897-1980) was an avid reader with an abiding interest in both social justice and Catholicism (which she explored on her own, culminating in her December 1927 baptism). She attended the University of Illinois for two years, but left college in 1916 to move to New York and join the budding socialist movement there. She worked for radical publications including The Masses and The Liberator, took part in numerous activist campaigns including the women’s suffrage movement (with which she was arrested and tortured in November 1917 for picketing outside the White House). She also wrote an autobiographical novel, The Eleventh Virgin (1924), which chronicled her fraught early 1920s affair with a fellow activist (Lionel Moise), including her difficult choice to have an abortion when she became pregnant.

All these early experiences illustrated Day’s attempts to combine personal reflection and spirituality with communal activism and social justice. But it was in the depths of the Great Depression that Day and a fellow radical Catholic activist would create a movement that truly exemplified those pursuits. In 1932 Day met Peter Maurin, an itinerant French monk and theologian who had recently immigrated to the U.S. from Canada. In collaboration with Maurin, Day developed the idea for a Catholic social movement dedicated both to confronting poverty and inequality and giving the working class the tools to advocate for their own liberation and justice. She launched that movement with the inaugural issue of a new newspaper, The Catholic Worker, published on May Day (May 1st), 1933.

In that newspaper’s first editorial, Day wrote, “For those who think that there is no hope for the future, no recognition of their plight, The Catholic Worker is being edited. It is printed to call their attention to the fact that the Catholic church has a social program.” The newspaper, like the movement it launched, advocated for labor actions, legal protections for workers and the poor, and radical charitable efforts, such as the St. Joseph House of Hospitality, the no-questions-asked soup kitchen and shelter that Day founded at the same time as the newspaper and ran for many decades thereafter. “Our rule,” Day wrote, “is the works of mercy.”

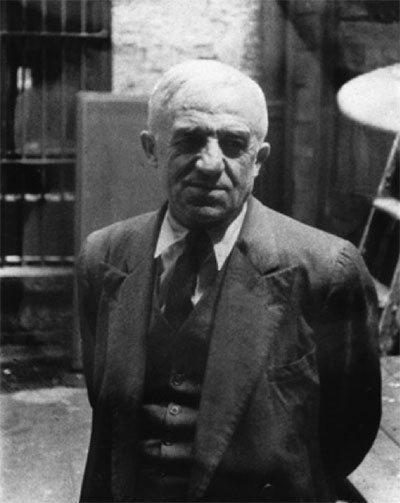

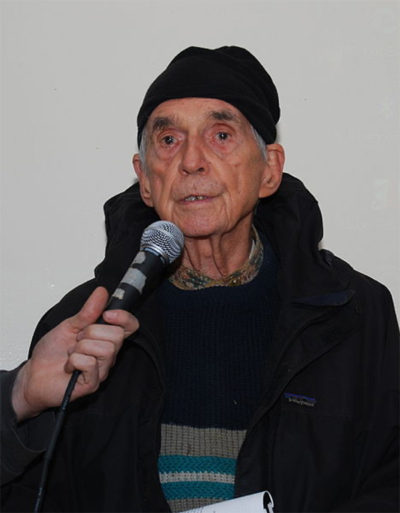

Day edited The Catholic Worker from its first issue through her death in 1980, and over those decades published and amplified the writings of such influential thinkers and activists as Thomas Merton and Daniel Berrigan. Day’s social justice activism extended far beyond the pages of the paper, however, as illustrated by her arrests at civil disobedience protests in 1955 (for refusing to participate in mandatory Cold War civil defense drills) and 1973 (at the age of 75, while picketing alongside labor leader Cesar Chavez in California). In response to such efforts, as well as her support for the Civil Rights Movement, her anti-Vietnam War pacifism, and more, the Jesuit magazine America dedicated an entire 1972 issue to Day, noting, “By now, if one had to choose a single individual to symbolize the best in the aspiration and action of the American Catholic community during the last forty years, that one person would certainly be Dorothy Day.”

Daniel Berrigan (Thomas Good / NLN via the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International, 3.0 Unported, 2.5 Generic, 2.0 Generic and 1.0 Generic license.)

Day also consistently modeled the kinds of thoughtful, critical self-reflection that is at the heart of lifelong spiritual pursuits and personal growth (as Scrooge learns from his three Ghosts). She did so as early as that 1924 autobiographical novel The Eleventh Virgin; but it was in her full autobiography, 1952’s The Long Loneliness, that she analyzed the many stages of her evolving identity, Catholicism, and activism with particular honesty and eloquence. As she writes in the opening chapter, “Confession,” “Going to confession is hard. Writing a book is hard, because you are ‘giving yourself away.’ But if you love, you want to give yourself. You write as you are impelled to write, about man and his problems, his relation to God and his fellows. You write about yourself because in the long run all man’s problems are the same, his human needs of sustenance and love.”

Day called that book “an account of myself, a reason for the faith that is in me.” Her self and her faith were likewise in the Catholic Worker movement, in her lifelong commitment to social justice, in her consistent attention to American communities too often left out of our conversations. Those efforts, like Day’s life and career, exemplify the true spirit of American spirituality and community, a spirit well worth celebrating in this holiday season.

Featured image: Dorothy Day, 1916 (Wikimedia Commons)