Considering History: Charlottesville and the Destructive Effects of White Supremacy

This series by American studies professor Ben Railton explores the connections between America’s past and present.

This week, just before the two-year anniversary of the August 2017 white supremacist and neo-Nazi rally in Charlottesville, my sons and I will once again drive down for our annual pilgrimage to my hometown. Last August, I used the dual occasions of that anniversary and that trip to write about Charlottesville’s largely hidden histories of Confederate memory and segregation, and how much the 2017 rally echoed those white supremacist legacies. Those lessons are more vital than ever in the summer of 2019.

Yet there are other hidden historical legacies in Charlottesville as well. One of the most pernicious is the longstanding erasure of African-American lives and communities, identities and histories, from both the city’s collective memories and its unfolding story. That erasure comprises one of white supremacy’s most deep and destructive effects, and is painfully relevant today.

One of those long-erased communities were the enslaved African Americans who built and sustained the University of Virginia. Rented enslaved laborers formed a core community during the university’s 1817-1825 construction, with the university paying more than $1,000 in hiring fees (more than $21,000 in contemporary value) to slave owners at the 1820-1821 height of activity. The 800,000-900,000 bricks used to construct the Rotunda, the university’s most famous structure, were manufactured by a group of 15 slaves in 1825. Once the university opened in 1825, enslaved men and women worked in numerous roles to keep it running, with an average of more than 100 enslaved laborers performing housekeeping, culinary, and personal service duties (such as blacking students’ shoes) throughout the pre-Civil War decades.

These enslaved men and women were also the frequent target of abuse and violence from the university’s elite male students. In November 1837, a group of drunken students beat the university bell-ringer, Lewis Commodore; just a few months later, in February 1838, two students savagely beat Fielding, a slave owned by mathematics professor Charles Bonnycastle, and the professor had to intervene “for the purpose of preventing his servant from being murdered.” In April 1850, three students abducted and raped a 17-year-old enslaved girl from Charlottesville; six years later, in 1856, student Noble Noland beat a 10- or 11-year-old enslaved girl unconscious because, he told the Faculty Committee, she had been “insolent to him” and such a beating was “not only tolerated by society, but with proper qualifications may be defended on the ground of the necessity of maintaining due subordination in this class of persons.” Noland, like many of these attackers, went unpunished.

For nearly two centuries, neither the University of Virginia nor the city of Charlottesville acknowledged this history of slavery and racism in any consistent public fashion. Much as Thomas Jefferson’s individual status as a slave owner was largely elided, (enslaved African Americans were frequently referred to as “servants” on tours of Monticello until the early 21st century), so too did narratives of Jefferson’s “academical village” highlight the space’s ideals and minimize (at best) the historical oppression on which it was literally built. Efforts are finally underway to redress those absences, including both the President’s Commission on Slavery and the University and a memorial to a cemetery for enslaved laborers. That cemetery had gone unmarked for more than 150 years, a telling reminder of both how fully this community had been buried and how much work remains to be done.

The destruction and burial of African American communities in Charlottesville continued long after the abolition of slavery, and indeed well into the 20th century. Over the course of the century’s early decades, the Vinegar Hill neighborhood, located between the city’s downtown shopping district and the university grounds, became one of Charlottesville’s most prominent African-American communities, featuring 140 homes, 30 black-owned businesses (everything from a jazz club to a fish market), and a church. As with so many African-American neighborhoods throughout the Jim Crow South (and an increasingly segregated nation), Vinegar Hill came to embody both the civic spaces into which African-American communities were forced and the resilience, solidarity, and power with which those communities responded.

Through a series of 1950s and 1960s efforts, however, Charlottesville demolished that neighborhood in the name of “urban renewal.” In January 1954 the City Council adopted a resolution critiquing the city’s large number of “unsanitary and unsafe inhabited dwelling accommodations”; after a very narrowly decided referendum vote, in June of that year the city established a Housing Authority to address this perceived problem. Over the next few years, that agency focused its attention on plans for “redeveloping” the Vinegar Hill neighborhood, which, as one supportive newspaper editorial put it, “is related closely with the rest of the downtown Charlottesville area which seriously needs room for expansion.” Expansion, redevelopment, renewal — these were all euphemisms for the unnecessary, overtly white supremacist displacement of a thriving African-American neighborhood.

In 1960, the Housing Authority proposed a referendum in support of “redeveloping” Vinegar Hill. Most of the city’s African-American residents could not vote in that referendum, thanks to a longstanding, racist poll tax. On June 14, 1960, the referendum narrowly passed, and by 1964 a plan was in place to bulldoze the entire neighborhood. Despite sustained opposition from African-American residents and their allies, in 1965 the neighborhood was razed, and most of its residents displaced to the city’s newly constructed Westhaven public housing project. Federal law required that the city provide such housing for residents it was displacing, although of course a unit in a project is no equivalent to a single-family home. Moreover, Westhaven was apparently as shoddily constructed as many of the era’s public housing projects, and by the 1980s many of its buildings were deteriorating.

Physician Mindy Thompson Fullilove has coined the term “root shock” to describe “the consequences of African American dispossession.” That shock, like the dispossession and destruction that cause it, is a purposeful and indeed central goal of white supremacy: to not only uproot American communities of color, but to make it impossible for those communities to endure as part of the civic life of cities and of the United States. Erased from both the landscape and memory, absent from both narratives of the past and visions of shared futures, these communities would too often, as Fullilove traces, experience “a profound shift in [their] political and social engagement” with both their local worlds and the nation.

That’s the crucial, tragic irony of white supremacist, exclusionary visions of America — in service of a mythic definition of a homogenous nation that never was, they seek to destroy the thriving, inclusive communities that truly define our shared identity. As I argue throughout my new book, We the People: The 500-Year Battle over Who is American, countering those exclusions requires acknowledging the communities and histories that exemplify an inclusive America. On the two-year anniversary of the Charlottesville white supremacist rally, remembering both enslaved laborers and the Vinegar Hill neighborhood would be a fitting response indeed.

Featured image: White supremacists clash with police in Charlottesville, VA, on August 12, 2017 (Evan Nesterak, Wikimedia Commons, via the Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license)

Considering History: Confederate Memorials, Racist Histories, and Charlottesville

This column by American studies professor Ben Railton explores the connections between America’s past and present.

On August 12th, 2017, as my sons and I drove from Boston to my childhood hometown of Charlottesville, Virginia for our annual visit with my parents, the small Central Virginia city erupted in violence. A gathering of white supremacists, neo-Confederates, and neo-Nazis known as the “Unite the Right” rally spurred counter-protests from antifa and other groups, and conflicts broke out again and again. In the day’s most horrific moment, a white supremacist named James Alex Fields Jr. drove his car into a group of counter-protesters, injuring thirty-five and murdering a young Charlottesville resident named Heather Heyer.

We’ll be driving down to Charlottesville again this coming weekend, on the one-year anniversary of those events. At the same time, many of the rally’s organizers and participants will be attending their own anniversary event, another “Unite the Right” rally in Washington, D.C. As that D.C. rally makes clear, these are national issues and conflicts that extend far beyond Charlottesville. Yet there are two distinct but interconnected histories within Charlottesville that provide vital contexts for these contemporary events: histories of Confederate memory and racial segregation.

Charlottesville saw no direct military action during the Civil War, but it was home to one of the war’s largest Confederate hospitals (which cared for more than 22,000 by the war’s end), and not coincidentally to one of its largest cemeteries for the Confederate dead (with more than 1000 buried there). For a few decades after the war, that cemetery remained largely private and unacknowledged. But in 1893 the Ladies’ Confederate Memorial Association (a predecessor to the Daughters of the Confederacy) dedicated a more formal Confederate Monument and Cemetery. The monument goes beyond the cemetery’s specific contexts to narrate a broader and striking reframing of Confederate memory, focused both on an idealization of the past and an extension of that heroic mythic history into the present, as it honors “the bravery, devotion, and performance of every Confederate soldier and the honor due every Confederate veteran.”

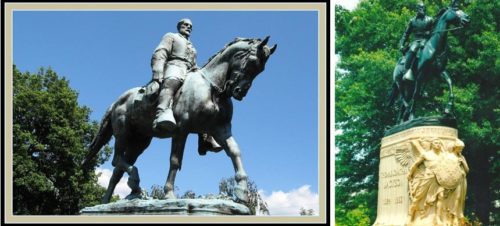

While the cemetery monument represented a significant step in the city’s memorialization of the Confederacy, it was more than two decades later that the city erected the now infamous downtown statues of Robert E. Lee and Stonewall Jackson. Dedicated in 1921 (Jackson) and 1924 (Lee), these statues were funded by, and constructed on land donated to the city by, Paul Goodlue McIntire, a local boy who had made a fortune on the New York Stock Exchange and returned to give much of it back to his hometown. McIntire also funded three other city parks and two different Charlottesville statues in honor of the Lewis and Clark expedition (Lewis was born in neighboring Albemarle county and the expedition set off from the area in 1804), so it’s fair to say that his interests in public land and collective memory extended well beyond the Confederacy. Yet the Lee and Jackson statues are located in Charlottesville’s most historic and central area, adjacent to its city hall and county courthouse (Jackson is directly outside the courthouse building), and thus occupy powerfully symbolic space in the city.

Moreover, there is at least one piece of direct evidence that McIntire’s public contributions were intended to preserve and further racial segregation in Charlottesville. As discovered by a Charlottesville Daily Progress reporter in 2009, the mid-1920s deed for the city’s McIntire Park, the only one of these McIntire-endowed parks named directly for the benefactor, includes this requirement: “Said property shall be held and used in perpetuity by the said City for a public park and playground for the white people of the City of Charlottesville.”

Of course all Southern cities practiced racial segregation in a variety of small and large ways throughout the Jim Crow era, but Charlottesville represents a particularly extreme case. That’s most especially true of the city’s public school system, which was one of the last in the United States to desegregate after the 1954 Brown v. Board of Education decision. All of the city’s public schools resisted desegregation for more than five years, supported by white supremacist officials such as U.S. Senator Harry Byrd and numerous members of the state General Assembly. The Assembly’s “massive resistance” bills gave Governor Lindsay Almond the authority to close any school where black and white students would attend together, and in the fall of 1958 he used that authority to close Charlottesville’s all-white Lane and Venable Elementary Schools for five months rather than admit African American students. All the city’s schools remained segregated throughout that school year, including Lane and Venable when they reopened in February 1959. That autumn, the first three African American students attended Lane High School, marking the start of integrated public education in the city. Although some Charlottesville public schools did not accept their first African American students for another year or two, the Supreme Court had ruled massive resistance unconstitutional in 1959, and the formal battle against educational integration in the city was over.

These were only the most nationally prominent of the city’s many late 1950s and 60s battles over integration. A mixed-race group of University of Virginia students and activists attempted to integrate the white-only University (movie) Theater in 1961, but the theater remained segregated until after the Civil Rights Act passed in July 1964. An even more overt conflict took place in 1963 at Buddy’s Restaurant, a popular establishment that, like many in the city, served only a white clientele. Inspired by the Civil Rights Movement’s demonstrations across the South, and supported by the local NAACP chapter, a mixed-race group of protesters led by community activists and ministers Floyd and William Johnson attempted to stage a sit-in at Buddy’s on Memorial Day in 1963. They were denied entrance to the restaurant and met with violence by white customers and counter-protesters; both Floyd and William Johnson were physically assaulted (Floyd had to spend two nights in the hospital), and other protesters including University of Virginia History Professor and Civil Rights ally Paul Gaston were likewise bloodied. The resulting press coverage caused a number of local establishments to voluntarily desegregate, but Buddy’s remained segregated until the Civil Rights Act passed—and then its owner Buddy Glover chose to close rather than desegregate.

All of these histories came together in the current movement to remove the city’s Confederate monuments. While that campaign has been driven in part by city councilors such as Kristin Szakos and Vice Mayor Wes Bellamy, another prominent argument for removing the statues came from Charlottesville public school students of color. Zyahna Bryant, an African American student at Charlottesville High School (my own alma mater), organized a March 2016 change.org petition to the City Council requesting that the Lee statue in particular be removed. Bryant and hundreds of her high school peers (along with many other Charlottesville residents) signed off on the statement, which reads in part, “As a younger African American resident in this city, I am often exposed to different forms of racism that are embedded in the history of the south and particularly this city. My peers and I feel strongly about the removal of the statue because it makes us feel uncomfortable and it is very offensive. I do not go to the park for that reason, and I am certain that others feel the same way.”

How each American community remembers the various histories out of which it has developed, and just as importantly how it engages with what has been included and what has been left out of its public and collective memories, are thorny and vital 21st century questions. Charlottesville is poised to help us answer those questions, but only if we resist the kinds of divisive and violent voices, and their white supremacist visions of the past, that dominated the city in August 2017.