Conflicts and debates over American identity have made frequent appearances in the news in recent days. The Washington Post contrasted Tucker Carlson’s anti-immigration rant about Representative Ilhan Omar with Megan Rapinoe’s arguments for an inclusive America, calling the moment representative of “one of America’s deepest political divides.” CNN responded to the controversy over Nike’s Betsy Ross flag sneakers with the headline, “This 4th of July, Americans are fighting over what ‘American’ should mean.” And Pew Research Religion shared the results of a poll in which nearly one third of Americans (and a majority of white evangelical Protestants) responded that “being a Christian is very important for being truly American.”

Conflicts and debates over American identity have made frequent appearances in the news in recent days. The Washington Post contrasted Tucker Carlson’s anti-immigration rant about Representative Ilhan Omar with Megan Rapinoe’s arguments for an inclusive America, calling the moment representative of “one of America’s deepest political divides.” CNN responded to the controversy over Nike’s Betsy Ross flag sneakers with the headline, “This 4th of July, Americans are fighting over what ‘American’ should mean.” And Pew Research Religion shared the results of a poll in which nearly one third of Americans (and a majority of white evangelical Protestants) responded that “being a Christian is very important for being truly American.”

There’s no doubt that this defining debate is everywhere in 2019 America. But in my new book We the People: The 500-Year Battle over Who is American, from Rowman and Littlefield’s American Ways series, I argue that this is a longstanding battle — indeed, that it is an originating, foundational, and consistent national conflict. We the People traces the battle between exclusionary and inclusive definitions of America across eight historical case studies and up to our contemporary era, highlighting in each case both moments of exclusion and inclusive alternatives in response to them.

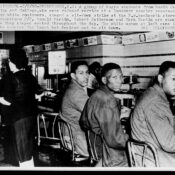

Some of those chapters expand upon and deepen topics about which I’ve written in this space, including slavery in the American Revolution, Mexican American communities and texts after the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, Chinese American lives and voices in the Chinese Exclusion Act era, and Japanese American soldiers and World War II internment camps. Here are glimpses of compelling American stories of exclusion and inclusion from three other chapters:

1. Native American resistance to Indian Removal: Andrew Jackson’s Indian Removal policy reflects precisely the endpoint of exclusionary attitudes: if Native Americans are defined as outside of American identity, forcing them out of the expanding nation in favor of European American settlers becomes a logical inevitability. But Native American voices and communities resisted both that policy and those attitudes: the Cherokee Memorials argued for that tribe’s legal and historical right to their American homelands; the Mashpee Revolt successfully resisted settler invasions and secured an American future for that Massachusetts community; and the speeches and essays of preacher and activist William Apess expressed an inclusive vision of American identity and history that linked Native Americans to those national images.

2. Fears and realities of Filipino Americans: In the first few decades of the 20th century, while the United States fought a multi-decade war of occupation in the Philippines, a set of xenophobic narratives was concurrently developed about Filipino Americans. These prejudices culminated in both massacres like the Watsonville (CA) riots and legal exclusions like the Filipino Repatriation Act of 1935. Yet in reality, Filipino Americans comprise the nation’s oldest Asian American community, extending back to Filipino villages in 18th century Spanish Louisiana, including Filipino American service in both the War of 1812 and the Civil War, and culminating in late 19th and early 20th century military, civic, and activist efforts from figures like General Vicente Lim, community organizer Agripino Jaucian, and labor leader Pablo Manlapit.

3. There’s no America without Muslim Americans: Muslim Americans have become central targets of 21st century exclusions, not only through particular laws like the Travel Ban, but also and especially through fears of “Sharia Law” and other narratives that define Muslims as entirely outside of American identity. Yet the truth is that every era and element of American history have included Muslim Americans: the centuries of enslaved Muslim Americans, from a foundational figure like Estevanico to the 19th century author Omar Ibn Said; the numerous contributions of Muslim Americans to the American Revolution and founding, from soldiers like Yusuf ben Ali to the Moroccan American community in Charleston (SC), which greatly influenced the nation’s first laws; and the inspiring late 19th and early 20th century stories of Muslim American individuals like Zarif Khan and communities like that in Cedar Rapids (IA), home to America’s oldest mosque still in operation today.

As the battle over American identity rages so fiercely around us today, it can be difficult to see a way through and past such divisions, and my book’s tracing of that battle across the 500 years of post-contact American history does indeed reflect its foundational and defining presence in our society. Yet in every moment and history of exclusion, we also find inspiring stories like these, figures and communities who embody and exemplify an inclusive vision of American identity. Through tracing both the exclusionary histories and the inclusive alternatives, We the People offers a vital guide to both understanding and transcending our divided current moment, a road map toward the more perfect union for which we continue to strive.

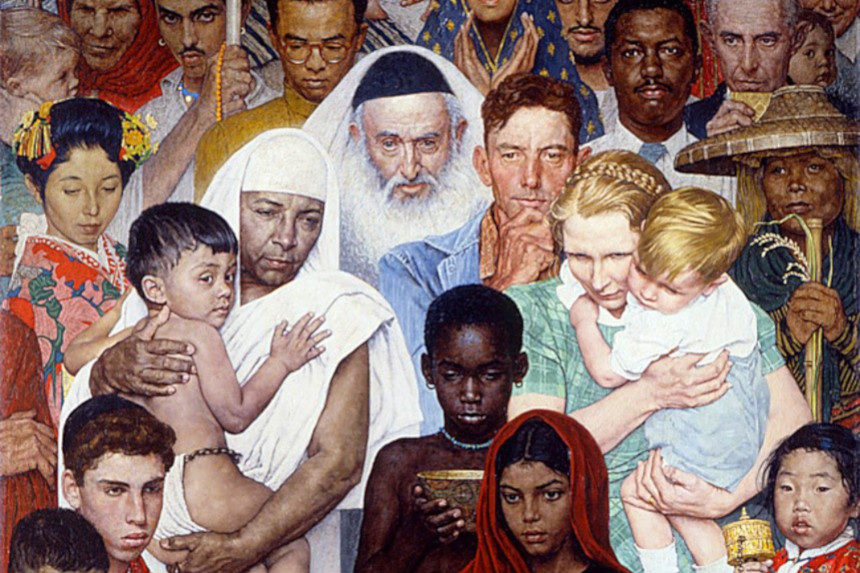

Featured image: Norman Rockwell; SEPS.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

As with every nations history there are injustices and parts of its history that warrant shame…….but, with the dawning of the United States of America in 1776 and later in 1787 with the drafting of its Constitution a new hope, the hope for a brighter light in civilization began. “A more perfect union” with “life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness” and “the rule of law” began to attract peoples from all over the world. It is still striving for that “perfection” which shall never be attained……but, reaching for it, attempting to attain it, has been the hallmark of our great nation.

The very first Christians where Jews, and Jewish converts, this was the case until militant Roman Catholic Evangelism emerged. Originally one of seven so called Christian churches in Europe, the Catholic Church with the aid of religious warfare and a better class of villainy became the dominant European faith even though not adverse to the making of false promises such as; “Join our church and obtain eternal life, or ‘You too can have entry into heaven for you and your family, and better still the Churches protection from the Devil’s embrace and wicked ways. If these promises did not work then the use of the sword, flame, slavery and the confiscation of your land, farm and property was always available to them – faith conversion methods that would have made Hitler and Stalin blush.

What is overlooked today is that the Catholic church insisted on all old and new members handing over a 10th of their earnings or crops to them each year, and if you failed to pay this tithe then they seized a 10th of your land, or the whole lot and you could go to hell. At first universal racism centred around a citizen’s skin colour, eye colour, hair colour, height, appearance, style of clothing and nationality, but these were rather weak arguments to preach and certainly less interesting when compared to: ‘Who was responsible for killing Jesus’ (not the Romans mind you who the Bible clearly states crucified him, that wouldn’t do, so the Jews had to take the hit) It was unfair but what else could the church leaders do then, someone had to take the blame and who better to blame than the harmless and often poverty-stricken Jews who were leaderless and had no arms or armour.

Thanks as always, Bob, and I can’t wait to hear your thoughts on the book!

I hear you on answers, but I certainly think better remembering and engaging our histories is one vital step. Glad to be in that work with ya.

Ben

I’m going to get your book, ‘We the People’ for a greater understanding of this very complex question and situation that only seems to get more so by the day. As far as answers go, I don’t know if there are any. Attempts to do so are only going to be met by controversy and arguing in today’s climate of hatred and instant snap judgments usually based on partial and/or false information and perceptions.