Horror for the Whole Family: Halloween Books for All Ages

Halloween is upon us once again. Last year, the Post looked at the question, “What’s the right horror film for the whole family?” And while staying in for movies is still an excellent choice for this spooky season, especially with the pandemic still present, films aren’t your only choice for eerie entertainment. So the new question becomes, “What are the right horror reads for the whole family?”

Every family’s view of content is different, and every family has a different standard for when it’s okay for the kids to indulge in scary fare. What we have here are some baseline recommendations, standout books that you might check out as starters, along with some appropriate ages. Again, your own idea of what’s appropriate and when may vary, but that’s why comment sections were created.

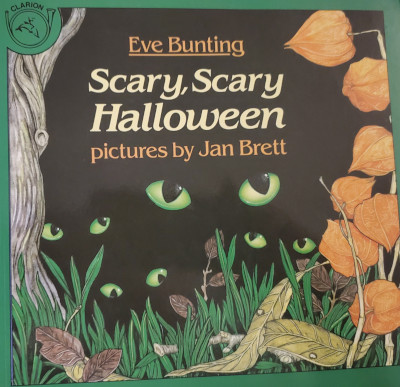

1.The Littles (9 and under): Scary, Scary Halloween by Eve Bunting and Jan Brett (1988)

Halloween-themed picture books abound, with lots of great, funny reads like Goblin Walk, but this one is a superlative effort from two huge talents. Eve Bunting has more than 250 books to her credit; she moves as easily from fiction to non-fiction as she does from picture books to novels. Jan Brett has been writing and drawing books for kids since the 1970s, and she’s received effusive praise for her lovely, intricate art. Scary, Scary Halloween brings them together in a delightful way, with rhyming verse and outstanding visual renditions of a scary Halloween night. An unseen narrator talks of monsters stalking through the neighborhood before the story takes not one, but two, surprise twists. It’s a great one to read to the little ones, and to have them read back to you as they get bigger.

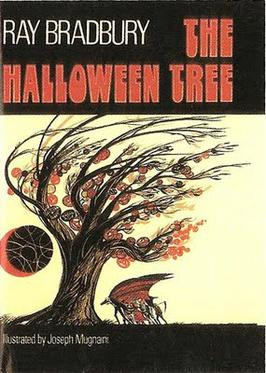

2. Kids to Tweens: The Halloween Tree by Ray Bradbury (1972)

Let’s be clear: Ray Bradbury’s The Halloween Tree is for EVERYONE, but it serves this particular demographic extremely well. Bradbury is, of course, one of the most exalted names in science fiction and fantasy, but he might also be the King of Halloween. His loving and nuanced takes on the holiday cause his name to appear repeatedly (and deservedly) on this list. The Halloween Tree is a touching story about friendship that also delves into the history of the holiday and its antecedent, Samhain. After a boy named Pipkin disappears, eight of his friends come together with the strange Mr. Moundshroud to travel through time to find their friend; along the way, they learn about the traditions of the Greeks, Romans, and Celts, visit medieval France, and witness what happens at Mexico’s Day of the Dead celebration. When the cost of saving Pipkin becomes clear, his friends come together for their friend in a moving finale.

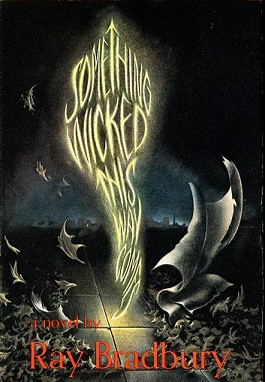

3. Teens: Something Wicked This Way Comes by Ray Bradbury (1962)

Today’s teens have access to a steady diet of horror material in both print and film; between libraries and streaming services, there’s not a lot that they haven’t already seen. That’s what makes Something Wicked This Way Comes special, in a way, because they might not have seen it. Bradbury’s 1962 masterpiece is all about the transition from youth to adulthood, while also baking in the regrets of age. When a strange carnival arrives in Green Town, Illinois on October 23, 13-year-old best friends Will Halloway (born one minute before midnight on October 30) and Jim Nightshade (born one minute after on October 31) are drawn into its orbit. At first, only Will and Jim seem aware of the unnatural events unfolding from the Cooger & Dark’s Pandemonium Shadow Show, but they find an unexpected ally in Will’s 54-year-old father. You can smell the autumn air in Bradbury’s rich descriptions of the season. The story, by turns wistful and terrifying, is one of the gold standards of dark fantasy. Teens can easily identify with the protagonists, as one of the primary forces in their own lives is the pull of adulthood.

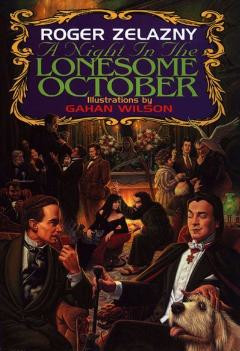

4. Adults: A Night in the Lonesome October by Roger Zelazney (1993) and October Dreams: A Celebration of Halloween (edited by Richard Chizmar and Robert Morrish, 2000)

A Night in the Lonesome October (not to be confused with Night in the Lonesome October by Richard Laymon, which is great in its own right) is creepy, funny, delightful, and demented. Zelazney was the celebrated writer of the bestselling The Chronicles of Amber series and dozens of other works; he won the Hugo Award six times and the Nebula three. 1993’s ANITLO was one his favorites of his own work; it was also his last novel, as he died in 1995. But what a great final statement it is. After an introduction, the 31 remaining chapters each take place on one day in October leading to Halloween in late 1800s London. The story is told from the point of view of Snuff, the canine companion and magical familiar of one Jack the Ripper. However, Jack is actually trying to save the world in a story that involves (either directly or by clever parody) the Lovecraft mythos, Dracula, Sherlock Holmes, the Wolf Man, the Frankenstein Monster, Rasputin, and more. The book is by turns haunting and hilarious, with Snuff and the other familiars alternately trying to help their masters save or destroy the world. Surprise alliances and betrayals abound, and it’s a real feat of imagination.

On the darker side, the 2000 anthology October Dreams: A Celebration of Halloween is simply one of the best collections about Halloween ever put to print. Collecting short stories along with non-fiction Halloween reminiscences by a murderer’s row of talent, the book includes the likes of Bradbury, Dean Koontz, Poppy Z. Brite, Christopher Golden, Jack Ketchum, Gahan Wilson, Richard Laymon, Dennis Etchison, Ramsey Campbell, Peter Straub, and many more. At over 650 pages, it’s a slab of fiendish goodness.

5. The Adult History Buff: Halloween: The History of America’s Darkest Holiday by David J. Skal (2016)

An October surprise bonus category! Yes, The Halloween Tree digs into the roots of the holiday, but this is a phenomenal book by one of the most authoritative writers on horror. Skal has written essential non-fiction like The Monster Show: A Cultural History of Horror, Hollywood Gothic, and Something in the Blood: The Untold Story of Bram Stoker, the Man Who Wrote Dracula. Here, he turns his keen insights to Halloween itself. Skal’s real talent lies in engaging a topic on both the macro and micro level, juxtaposing how that topic impacts the culture as a whole while also using laser-precise examples to show just how deeply that impact runs. Skal’s examination runs the gamut from the early Celtic days to a present where we (in non-pandemic years) spend about $9 billion celebrating the holiday.

6. Grandparents: Ghost Story by Peter Straub (1979)

This one goes off theme just a tiny bit, but bear with it. Yes, Ghost Story takes place across multiple time periods with one of the most climactic sequences occurring during a blizzard. But it is one of the grand champions of scary storytelling, and the initial protagonists are a group of older gentlemen and one gentleman’s wife. With many mature main characters and Straub’s deep appreciation for the canon and history of American horror (references to Nathaniel Hawthorne and Donald Wandrei abound, and nods are clearly made to George Romero and Straub’s pal Stephen King), Straub crafts a particularly literary story that thrives on human emotion. There is some really dark stuff, but there are also seeds of hope, especially when the older men reach out to two other protagonists (one much younger) to help them navigate the terror that has them under siege.

And there you have it: like the film list, it’s a list to get you started (and to start discussions). Enjoy this very strange season, get lost in the books that you intend to read, and maybe, just maybe, leave a light on.

Featured image: Marsan / Shutterstock

The Creepy and Harsh Lessons of Early Children’s Books

If Maurice Sendak’s fanciful Where the Wild Things Are had been published in the early 1700s, its misbehaving protagonist might have met a violent — and even impious — death at the jaws of the book’s imaginative monsters. Modern children’s literature, from the fantastical to the heartfelt to the amusing, is often treasured as a token of the innocence of childhood, but this country’s earliest kids’ books bear little resemblance to today’s colorful tales. Rather than inventive, naïve minds to be cultivated with whimsy, children were perceived as wicked fools whose basest, sinful instincts ought to be culled early.

Many of the earliest publications for children were lost to wear and tear, and collectors didn’t often consider them valuable investments. Dr. A.S.W. Rosenbach, however, amassed these works in the early 1900s, finding them to be strange and telling artifacts of the early culture of the United States. Writing in this magazine in 1927, Rosenbach declared, “Today I have nearly 800 volumes, which date from 1682 to 1840. They reveal with amazing fidelity the change in juvenile reading matter, the change, too, in the outward character of the American child.”

One of the most striking differences in the early children’s literature, owing to the strict puritanical culture of the colonists, was the presiding principle that children were not “born to live, but born to dye [sic],” and, as Rosenbach claims, “the literature provided for them was with the definite purpose of teaching them how they should die in a befitting manner.”

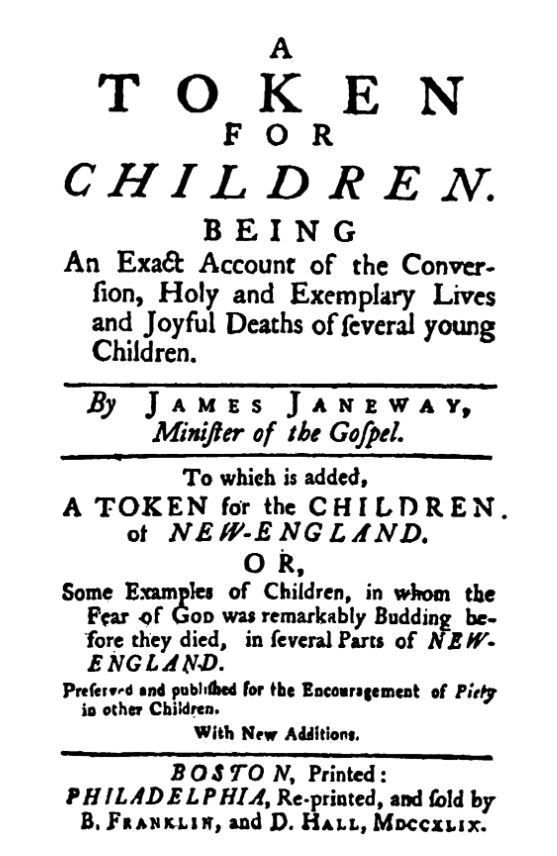

Long-winded titles like A Legacy for Children; Being Some of the Last Expressions and Dying Sayings of Hannah Hill, Junior and A Token for Children: Being an Exact Account of the Conversion, Holy and Exemplary Lives, and Joyful Deaths of Several Young Children promised to set a pious example for young readers. In 1708, Nathaniel Crouch’s Some Excellent Verses for the Education of Youth, printed in Boston, featured the salvo “Though I am Young, yet I may Die/ And hasten to Eternity:/ There is a dreadful fiery Hell,/ Where Wicked ones must always dwell.”

Publishers scarcely hesitated to stretch the truth in attempts to mold young minds. A Token for Children presents the story of Elizabeth Butcher, who, “when she was about two years and half old; as she lay in the cradle, she would ask herself that question, what is my corrupt Nature? And would make answer again to herself, it is empty of grace, bent unto Sin, and only to Sin, and that continually. She took great delight in learning her catechism, and would not willingly go to bed without saying some part of it.”

Teaching children about death likely seemed a reasonable pursuit in an age of rampant contagious diseases and pervasive child mortality. It would have been necessary to portray the inevitable not as tragedy but as a joyous entrance to the afterlife.

Rosenbach boasted that his supreme collection of this morbid literature contained the only known copy of a collection of poetry printed by T. Green in New Haven in 1740. One of its poems, called “The Play,” offered a somewhat playful passage that children could recite:

Now from School I haste away,

And joyful rush along to play;

Eager I for my marbles call,

The whistling top or bouncing Ball.

The changing marbles to me show,

How mutable all things below.

My fate and theirs may be the same

Dasht in an instant from the Game.

The Hoop, swift rattling on the Chase,

Shows me how quick Life runs its Race.

My hoop and I like turnings have,

So fast Death drives me to my Grave.

The Prodigal Daughter, published in 1736 by Thomas Fleet, begins with a warning: “Let every wicked graceless child attend/ And listen to these lines that here are pen’d,/ God grant it may to all a warning be,/ To love their friends and shun bad company.” In the haunting story, a young girl, obsessed with worldly vanities, makes a deal with the devil to poison her parents after they lock her in her room. She is struck dead, but at her funeral, the prodigal child awakens from her sleep to take the sacrament and rejoice in her newfound obedience to her parents.

As Rosalie V. Halsey claims in Forgotten Books of the American Nursery, “the slow growth of a literature written with an avowed intention of furnishing amusement as well as instruction” started around the middle of the 18th century. Some volumes following this period offered less puritanical advice for children to go about their days. The threat of death (or mutilation), however, was still omnipresent. Halsey calls the early 19th century an era marked by “chronic anxiety” in children’s literature.

This anxiety is evident in The Daisy, written by Elizabeth Turner in 1839. Turner’s book of verse is a series of lessons for young people, teaching them to learn spelling, treat well the poor, and otherwise avoid naughtiness. Some warnings are more drastic than others, however, like “Poisonous Fruit”:

As Tommy and his sister Jane

Were walking down a shady lane,

They saw some berries, bright and red,

That hung around and over head.

And soon the bough they bended down,

To make the scarlet fruit their own;

And part they eat, and part in play

They threw about and flung away.

But long they had not been at home

Before poor Jane and little Tom

Were taken sick and ill, to bed,

And since, I’ve heard, they both are dead.

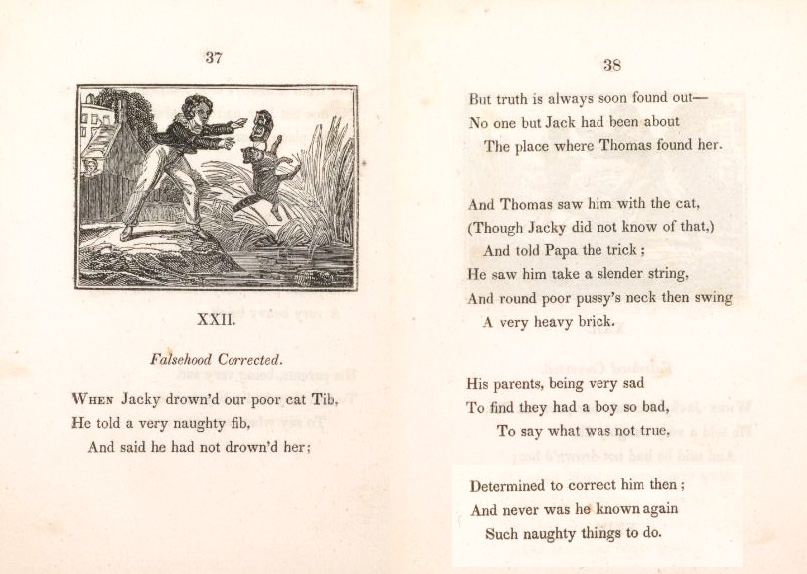

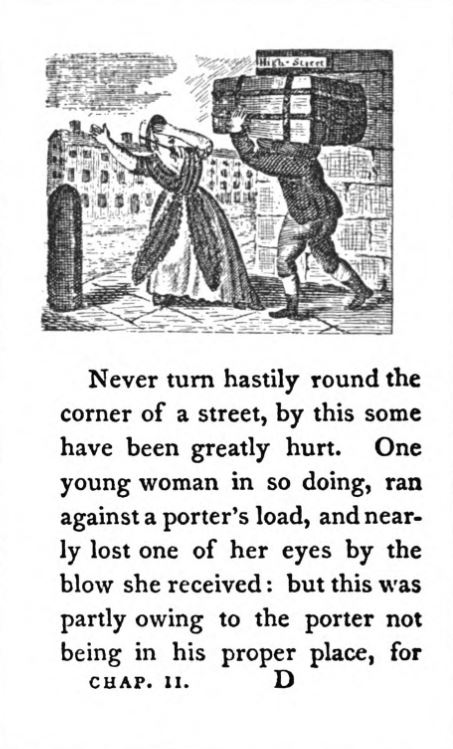

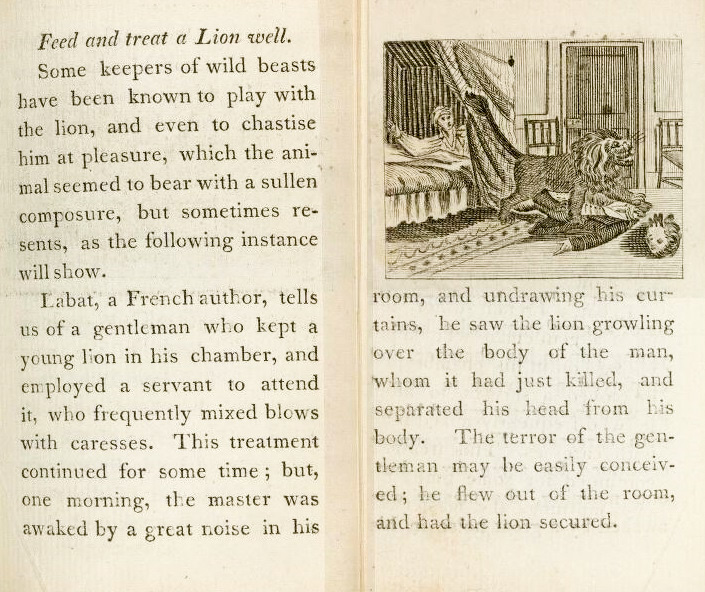

Another series, The First (and Second and Third) Chapter of Accidents and Remarkable Events, Containing Caution and Instruction for Children, was originally published in England by William Darton and reprinted in the U.S. in the early 1800s. The events therein are indeed remarkable, and highly unlikely, but nevertheless portrayed as possible pitfalls in a child’s life. Characters in the series are mauled by lions and tigers, fall out of hot air balloons, and plummet from bridges on horseback.

Lessons in carelessness and vanity are still central themes of children’s literature, but it would be a mighty task to locate modern cautionary tales as extreme as those that circulated the country several centuries ago. These stories and rhymes, largely lost in the passing years, give a snapshot of, as Rosenbach writes, “the mental food our poor ancestors lived upon in the dim days of their childhood.”

Featured image: Illustration from The Prodigal Daughter, Graphic Arts Collection, Special Collections, Firestone Library, Princeton University