If Maurice Sendak’s fanciful Where the Wild Things Are had been published in the early 1700s, its misbehaving protagonist might have met a violent — and even impious — death at the jaws of the book’s imaginative monsters. Modern children’s literature, from the fantastical to the heartfelt to the amusing, is often treasured as a token of the innocence of childhood, but this country’s earliest kids’ books bear little resemblance to today’s colorful tales. Rather than inventive, naïve minds to be cultivated with whimsy, children were perceived as wicked fools whose basest, sinful instincts ought to be culled early.

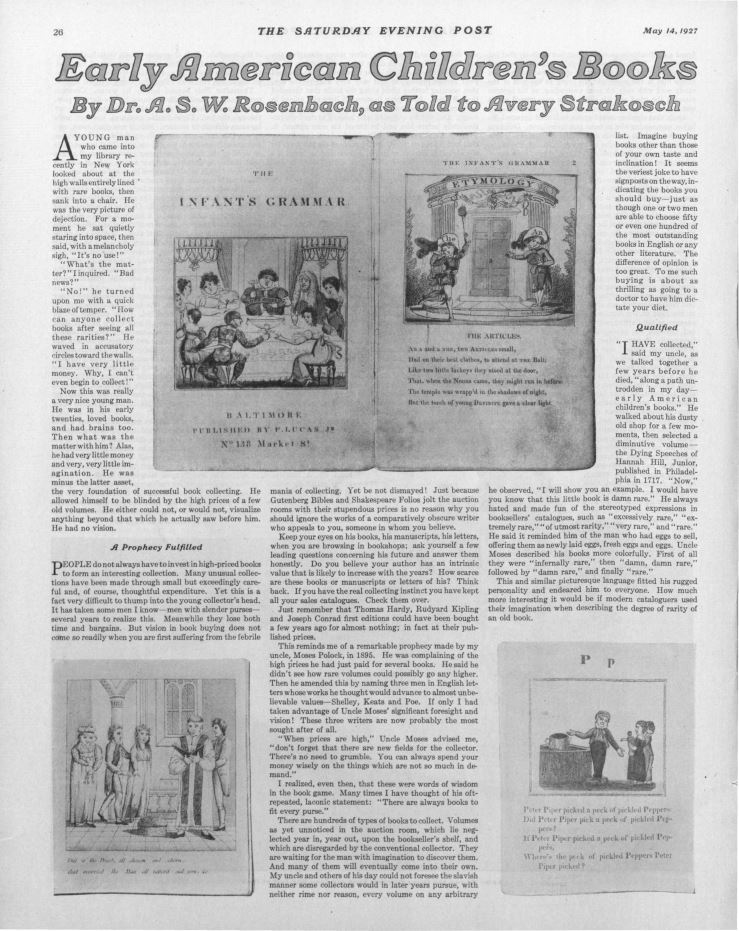

Many of the earliest publications for children were lost to wear and tear, and collectors didn’t often consider them valuable investments. Dr. A.S.W. Rosenbach, however, amassed these works in the early 1900s, finding them to be strange and telling artifacts of the early culture of the United States. Writing in this magazine in 1927, Rosenbach declared, “Today I have nearly 800 volumes, which date from 1682 to 1840. They reveal with amazing fidelity the change in juvenile reading matter, the change, too, in the outward character of the American child.”

One of the most striking differences in the early children’s literature, owing to the strict puritanical culture of the colonists, was the presiding principle that children were not “born to live, but born to dye [sic],” and, as Rosenbach claims, “the literature provided for them was with the definite purpose of teaching them how they should die in a befitting manner.”

Long-winded titles like A Legacy for Children; Being Some of the Last Expressions and Dying Sayings of Hannah Hill, Junior and A Token for Children: Being an Exact Account of the Conversion, Holy and Exemplary Lives, and Joyful Deaths of Several Young Children promised to set a pious example for young readers. In 1708, Nathaniel Crouch’s Some Excellent Verses for the Education of Youth, printed in Boston, featured the salvo “Though I am Young, yet I may Die/ And hasten to Eternity:/ There is a dreadful fiery Hell,/ Where Wicked ones must always dwell.”

Publishers scarcely hesitated to stretch the truth in attempts to mold young minds. A Token for Children presents the story of Elizabeth Butcher, who, “when she was about two years and half old; as she lay in the cradle, she would ask herself that question, what is my corrupt Nature? And would make answer again to herself, it is empty of grace, bent unto Sin, and only to Sin, and that continually. She took great delight in learning her catechism, and would not willingly go to bed without saying some part of it.”

Teaching children about death likely seemed a reasonable pursuit in an age of rampant contagious diseases and pervasive child mortality. It would have been necessary to portray the inevitable not as tragedy but as a joyous entrance to the afterlife.

Rosenbach boasted that his supreme collection of this morbid literature contained the only known copy of a collection of poetry printed by T. Green in New Haven in 1740. One of its poems, called “The Play,” offered a somewhat playful passage that children could recite:

Now from School I haste away,

And joyful rush along to play;

Eager I for my marbles call,

The whistling top or bouncing Ball.

The changing marbles to me show,

How mutable all things below.

My fate and theirs may be the same

Dasht in an instant from the Game.

The Hoop, swift rattling on the Chase,

Shows me how quick Life runs its Race.

My hoop and I like turnings have,

So fast Death drives me to my Grave.

The Prodigal Daughter, published in 1736 by Thomas Fleet, begins with a warning: “Let every wicked graceless child attend/ And listen to these lines that here are pen’d,/ God grant it may to all a warning be,/ To love their friends and shun bad company.” In the haunting story, a young girl, obsessed with worldly vanities, makes a deal with the devil to poison her parents after they lock her in her room. She is struck dead, but at her funeral, the prodigal child awakens from her sleep to take the sacrament and rejoice in her newfound obedience to her parents.

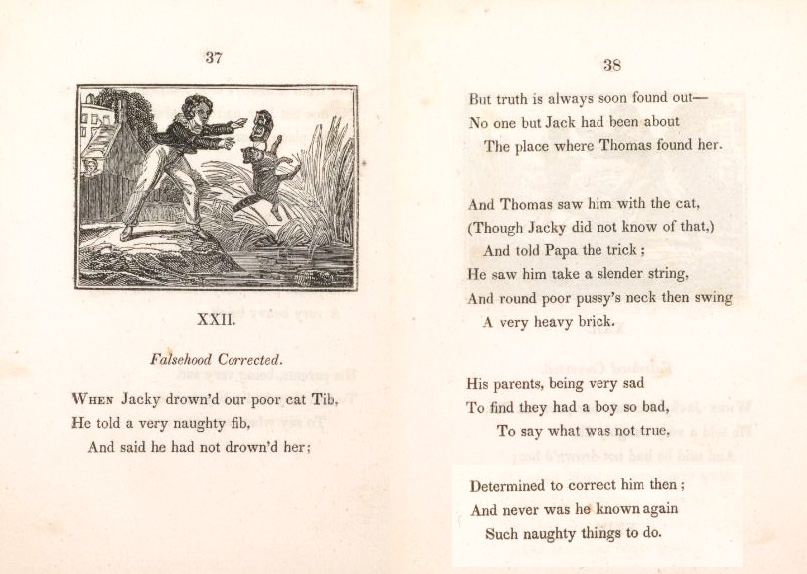

As Rosalie V. Halsey claims in Forgotten Books of the American Nursery, “the slow growth of a literature written with an avowed intention of furnishing amusement as well as instruction” started around the middle of the 18th century. Some volumes following this period offered less puritanical advice for children to go about their days. The threat of death (or mutilation), however, was still omnipresent. Halsey calls the early 19th century an era marked by “chronic anxiety” in children’s literature.

This anxiety is evident in The Daisy, written by Elizabeth Turner in 1839. Turner’s book of verse is a series of lessons for young people, teaching them to learn spelling, treat well the poor, and otherwise avoid naughtiness. Some warnings are more drastic than others, however, like “Poisonous Fruit”:

As Tommy and his sister Jane

Were walking down a shady lane,

They saw some berries, bright and red,

That hung around and over head.

And soon the bough they bended down,

To make the scarlet fruit their own;

And part they eat, and part in play

They threw about and flung away.

But long they had not been at home

Before poor Jane and little Tom

Were taken sick and ill, to bed,

And since, I’ve heard, they both are dead.

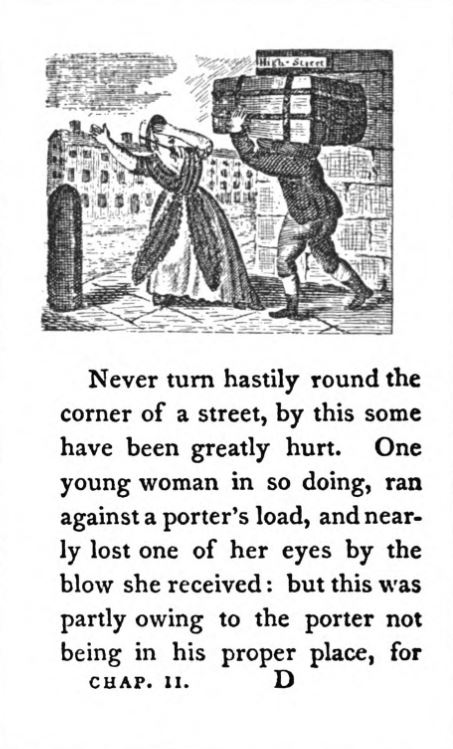

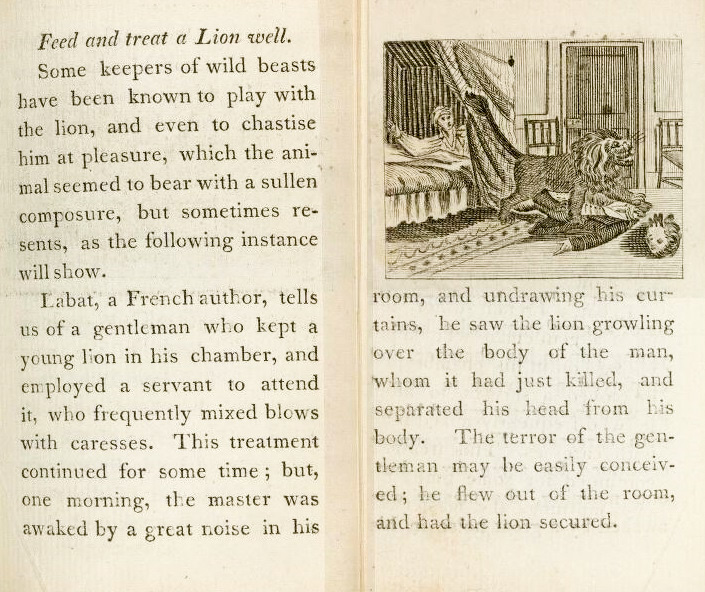

Another series, The First (and Second and Third) Chapter of Accidents and Remarkable Events, Containing Caution and Instruction for Children, was originally published in England by William Darton and reprinted in the U.S. in the early 1800s. The events therein are indeed remarkable, and highly unlikely, but nevertheless portrayed as possible pitfalls in a child’s life. Characters in the series are mauled by lions and tigers, fall out of hot air balloons, and plummet from bridges on horseback.

Lessons in carelessness and vanity are still central themes of children’s literature, but it would be a mighty task to locate modern cautionary tales as extreme as those that circulated the country several centuries ago. These stories and rhymes, largely lost in the passing years, give a snapshot of, as Rosenbach writes, “the mental food our poor ancestors lived upon in the dim days of their childhood.”

Featured image: Illustration from The Prodigal Daughter, Graphic Arts Collection, Special Collections, Firestone Library, Princeton University

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

This feature (subject matter-wise) is truly awful, but God is it well written and simply wonderful! This is one of the wildest rides yet to date that I’ve been on (on) this website, Nicholas. You find the most fascinating and unexpected things to write about from the archives; I’m not kidding—-at all!

I want to read the 1927 story per the link here (thank you) when I’ll have more time on Friday. Meanwhile these stories and rhymes about children eating poisonous fruit, falling out of hot air balloons, being mauled by wild animals and more are downright terrifying.

Things are stressful and scary enough for children today as it is. At least their stories and poems are not like these. It’s a bit much for an adult to read some of this material now. Had a product like Depends for children existed then, they might have sold quite well. I can see the teachers back then sending the kids home with a note stating: “Tomorrow shalt be poem and children’s story day; thou fasten the Depends on thy child in advance, to prevent thy child from having to clean up thine own bodily mess! No janitor shalt be here with sawdust. Remember that, lest ye be intentionally foolish after my warning. Be gone with such notions, or get out of my classroom!”