Little Women Among the Casualties

This is the fifth installment of our six-part series on the Civil War, marking the 150th anniversary of the Battle of Gettysburg. To recap: In part one, “The News from Gettysburg: A Hazardous Move,” we described how the Post reported the initial news of the invasion. In part two, “Scrambling for Soldiers,” we looked at the renewed attention to the draft. In part three, “Americans United to Support the Civil War Troops,” we covered a special organization of volunteers who helped save thousands of soldiers’ lives. And in part four, “Where the Civil War was Won,” we looked at the Post’s war coverage from the battlefield.

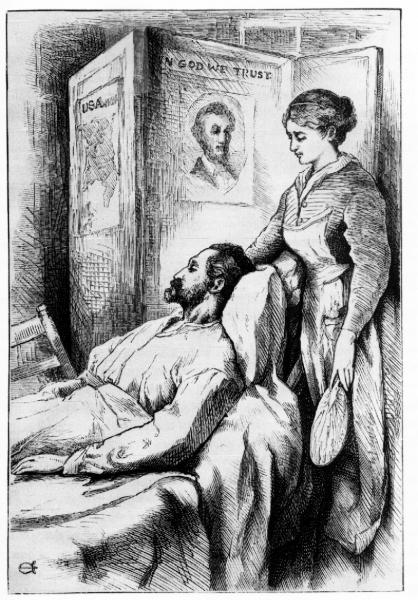

American novelist Louisa May Alcott knew firsthand the terrible price of victory in the Civil War. From 1862 to 1863, she cared for wounded soldiers at a military hospital in Georgetown, D.C.

She wrote about her experiences in a series of letters for the abolitionist paper, Boston Commonwealth. The entire series of letters, published as Hospital Sketches in 1863, earned Alcott her first public attention as an author and praise for her sensitivity and wit.

Five years later, she became one of America’s foremost writers with her classic novel Little Women.

The Post published this excerpt on July 25, 1863, just a few weeks after Gettysburg, when Union hospitals were overflowing with the thousands of casualties from the battle. Here, Alcott describes her first day on duty in December 1862, when the hospital received grievously wounded soldiers from Fredericksburg.

Hospital Sketches by Miss Louisa M. Alcott

“Which naming no names, no offence could be took.”

— Sairy GampThey’ve come! they’ve come! Hurry up, ladies—you’re wanted.”

“Who have come? the rebels?”This sudden summons in the gray dawn was somewhat startling to a three days’ nurse like myself, and, as the thundering knock came at our door, I sprang up in my bed, prepared

“To gird my woman’s form,

And on the ramparts die,”if necessary; but my room-mate took it more coolly, and, as she began a rapid toilet, answered my bewildered question,—(“Bless you, no child; it’s the wounded from Fredericksburg; forty ambulances are at the door, and we shall have our hands full in fifteen minutes.”)

Arrival of the Wounded

The sight of several stretchers, each with its legless, armless, or desperately wounded occupant, entering my ward, admonished me that I was there to work, not to wonder or weep; so I corked up my feelings, and returned to the path of duty, which was rather “a hard road to travel” just then.The house had been a hotel before hospitals were needed, and many of the doors still bore their old names; some not so inappropriate as might be imagined, for my ward was in truth a ball-room, if gun-shot wounds could christen it.

Forty beds were prepared, many already tenanted by tired men who fell down anywhere, and drowsed till the smell of food roused them. Round the great stove was gathered the dreariest group I ever saw—ragged, gaunt and pale, mud to the knees, with bloody bandages untouched since put on days before; many bundled up in blankets, coats being lost or useless; and all wearing that disheartened look which proclaimed defeat, more plainly than any telegram of the Burnside blunder. I pitied them so much, I dared not speak to them, though, remembering all they had been through since the route at Fredericksburg, I yearned to serve the dreariest of them all. Presently, Miss Blank tore me from my refuge behind piles of one-sleeved shirts, odd socks, bandages and lint; put basin, sponge, towels, and a block of brown soap into my hands, with these appalling directions:

“Come, my dear, begin to wash as fast as you can. Tell them to take off socks, coats and shirts, scrub them well, put on clean shirts, and the attendants will finish them off, and lay them in bed.”

If she had requested me to shave them all, or dance a hornpipe on the stove funnel, I should have been less staggered; but to scrub some dozen lords of creation at a moment’s notice, was really–really–. However, there was no time for nonsense, and, having resolved when I came to do everything I was bid, I drowned my scruples in my wash-bowl, clutched my soap manfully, and, assuming a business-like air, made a dab at the first dirty specimen I saw, bent on performing my task vi et armis (by force of arms) if necessary.

I chanced to light on a withered old Irishman, wounded in the head, which caused that portion of his frame to be tastefully laid out like a garden, the bandages being the walks, his hair the shrubbery. He was so overpowered by the honor of having a lady wash him, as he expressed it, that he did nothing but roll up his eyes, and bless me, in an irresistible style which was too much for my sense of the ludicrous; so we laughed together, and when I knelt down to take off his shoes, he “flopped” also, and wouldn’t hear of my touching “them dirty crayters. May your bed above be aisy darlin’, for the day’s work ye ar doon! —Whoosh! there ye are, and bedad, it’s hard tellin’ which is the dirtiest, the fut or the shoe.” It was; and if he hadn’t been to the fore, I should have gone on pulling, under the impression that the “fut” was a boot, for trousers, socks, shoes and legs were a mass of mud. This comical tableau produced a general grin, at which propitious beginning I took heart and scrubbed away like any tidy parent on a Saturday night.

Some of them took the performance like sleepy children, leaning their tired heads against me as I worked, others looked grimly scandalized, and several of the roughest colored like bashful girls. One wore a soiled little bag about his neck, and, as I moved it, to bathe his wounded breast, I said,

“Your talisman didn’t save you, did it?”“Well, I reckon it did, ma’am, for that shot would a gone a couple a inches deeper but for my old mammy’s camphor bag,” answered the cheerful philosopher.

Another, with a gun-shot wound through the cheek, asked for a looking-glass, and when I brought one, regarded his swollen face with a dolorous expression, as he muttered—

“I vow to gosh, that’s too bad! I warn’t a bad looking chap before, and now I’m done for; won’t there be a thunderin’ scar? and what on earth will Josephine Skinner say?”

He looked up at me with his one eye so appealingly, that I controlled my risibles, and assured him that if Josephine was a girl of sense, she would admire the honorable scar, as a lasting proof that he had faced the enemy, for all women thought a wound the best decoration a brave soldier could wear. I hope Miss Skinner verified the good opinion I so rashly expressed of her, but I shall never know.

The next scrubbee was a nice looking lad, with a curly brown mane, and a budding trace of gingerbread over the lip, which he called his beard, and defended stoutly, when the barber jocosely suggested its immolation. He lay on a bed, with one leg gone, and the right arm so shattered that it must evidently follow: yet the little Sergeant was as merry as if his afflictions were not worth lamenting over; and when a drop or two of salt water mingled with my suds at the sight of this strong young body, so marred and maimed, the boy looked up, with a brave smile, though there was a little quiver of the lips, as he said,

“Now don’t you fret yourself about me, miss; I’m first rate here, for it’s nuts to lie still on this bed, after knocking about in those confounded ambulances that shake what there is left of a fellow to jelly. I never was in one of these places before, and think this cleaning up a jolly thing for us, though I’m afraid it isn’t for you ladies.”

“Is this your first battle, Sergeant?”

“No, miss; I’ve been in six scrimmages, and never got a scratch till this last one; but it’s done the business pretty thoroughly for me, I should say. Lord! what a scramble there’ll be for arms and legs, when we old boys come out of our graves, on the Judgment Day: wonder if we shall get our own again? If we do, my leg will have to tramp from Fredericksburg, my arm from here, I suppose, and meet my body, wherever it may be.”

The fancy seemed to tickle him mightily.

Coming Next: The Work of the Sanitary Commission Inspires Another Convert

Where the Civil War was Won

This is the fourth installment of our six-part series on the Battle of Gettysburg. To recap: In part one, “The News from Gettysburg: A Hazardous Move,” we described how the Post reported the initial news of the invasion. In part two, “Scrambling for Soldiers,” we looked at the renewed attention to the draft. And in part three, “Americans United to Support the Civil War Troops,” we covered a special organization of volunteers who helped save thousands of soldiers’ lives.

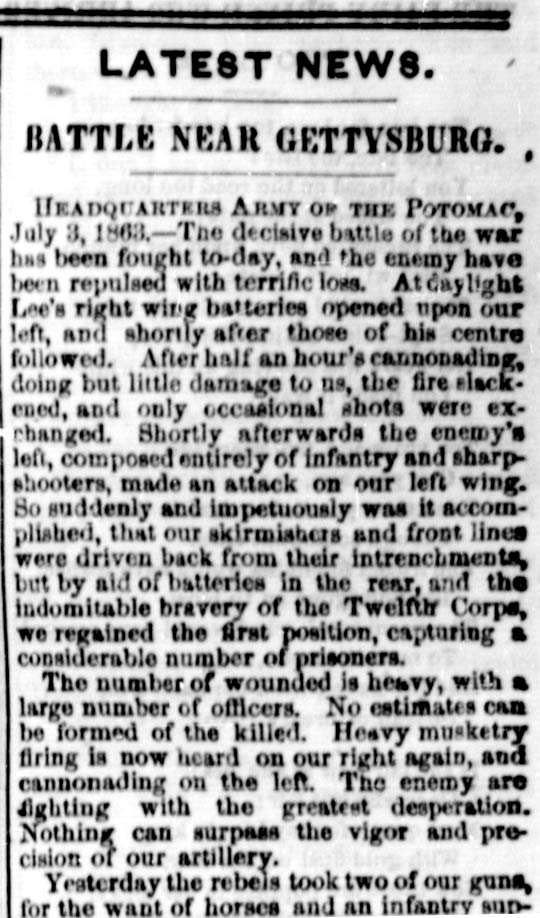

Unfortunately, the Post didn’t have regular reports from correspondents in the field like the major newspapers. So the editors provided bulletins taken from military dispatches telegraphed to Washington, D.C., which were inserted just before the paper went to press. For example, the July 1863 issue included this update:

HARRISBURG, June 28, P.M.—The capital of the state is in danger. The enemy is within four miles of our works and advancing. The cannonading has been distinctly heard for three hours. … Rebels have occupied successively [nine towns] and are now spread over all the region lying between the Susquehanna and Laurel Ridge. Not a single point in that whole section remains in our possession.

Some of the Post’s war coverage reflects the values peculiar of those times. While modern readers might want to know more about the experiences of the fighting men, the Post editors felt it was important to report how many cannons and flags were lost in battle. They also gave much coverage to the cavalry, which was assumed to be essential to an army’s success. A Post writer observed, “On a field of warfare where the distances are so great, the cavalry arm of the service is not only useful but absolutely indispensable.” At Gettysburg, we now know, the cavalry played a minor role, which barely affected the outcome of the battle. The battle was won by the men of the Union infantry and artillery who withstood massive Confederate assaults all along the Union lines.

In hindsight it’s interesting to note that the Post gave slight coverage to what would become one of the most memorable events of the Civil War. Shortly after the shooting had stopped on the battlefield, a correspondent filed this report:

HEADQUARTERS, ARMY OF POTOMAC, JULY 3—At daylight, Lee’s right wing batteries opened upon our left, and shortly after those of his centre followed. After half an hour’s cannonading, doing but little damage to us, the fire slackened, and only occasional shots were exchanged. Shortly afterwards, the enemy’s center, composed entirely of infantry and sharpshooters, made an attack on our left wing. So suddenly and impetuously was it accomplished, that our skirmishers and front lines were driven back from their entrenchments …

With these few words, the reporter covered what would become one of the most famous events of the battle: the attack on Cemetery Ridge by three Confederate Generals: Maj. Gen. Isaac R. Trimble, Brig. Gen. J. Johnston Pettigrew, and Maj. Gen. George Pickett.

Pickett’s Charge, as it came to be known, began on the afternoon of July 3, 1863, when 13,000 rebel soldiers emerged from the woods west of Emmitsburg Road. They formed themselves into two lines of battle more than 1 mile wide and marched, not charged, straight toward the waiting Yankee line. Before them lay 1,400 yards of open fields that rose gradually to a ridge where the Union infantry and artillery had an unobstructed line of fire. The Confederates tried to hold their formation, but the line became disjointed as the soldiers had to climb fences to proceed. And, as the Union cannon fire began, great holes appeared in the line. The gaps grew wider as the rebels came within range of the Union muskets. Before the Confederates reached the crest of the ridge, half of their number had been killed or wounded. Yet the rebels continued on with a relentless, steady pace until, within yards, they finally broke into a charge. They slammed into the Union line and began a fighting hand-to-hand struggle with the Yankee defenders. For a few minutes, the outcome of the battle and, some say, of the war, hung in the balance as Northern and Southern soldiers crowded at the breached Union line.

For the Confederates, a breakthrough here would cut the Union Army in two, a victory that would culminate two years of fighting in which the Union had not won a single, definitive victory against Lee’s men. Lee wanted this victory, not just to clear the way for marching into Baltimore or Washington, D.C., but to destroy the North’s morale.

For the Union, however, this was not just another battle. The Federals had seen two years of fighting in a long, frustrated struggle to seize the Confederate capitol at Richmond, Virginia. They were well acquainted with defeat; General Lee had defeated them so often that many were starting to believe he was invincible. Now, here was Lee in the North with the 70,000 men of his formidable Army of Northern Virginia.

The Union soldiers knew that the outcome of this fight would decide the fate of their army and their country. On Wednesday and Thursday, they had fought with growing desperation as the rebel army broke through their defenses three times. Each time, Union reserves appeared at the last minute to hold the line. Yet each save had extracted a heavy cost. The divisions on the right and left of the Union line probably wouldn’t withstand one more attack. Fortunately for the Union, on the third day, the rebels had chosen to attack the center of the line.

And so, sometime around 3:30 p.m. on July 3, 1863, a crowd of gray uniforms spilled over the low stone wall on Cemetery Ridge. The Union soldiers gathered to push them back. Soon there was a dense crowd at the wall fighting hand-to-hand, the men were packed so tightly that many of the soldiers couldn’t even use their rifles as clubs.

And then—

… by aid of batteries in the rear, and the indomitable bravery of the Twelfth Corps, we regained the first position, capturing a considerable number of prisoners.

The Post’s correspondent didn’t recognize the history held within that paragraph of news, but he was surprisingly farsighted in his judgment. Because even with the rebel army still on the field, with both armies exhausted and no one quite certain that Lee wouldn’t try another attack, he felt confident to write the enemy had been repulsed in—as he called it—“the decisive battle of the war.”

Coming Next: Little Women in a Military Hospital

Scrambling for Troops

This is the second installment of our six-part series on the lead up to Gettysburg. Click here to read part one, “The News from Gettysburg: A Hazardous Move.”

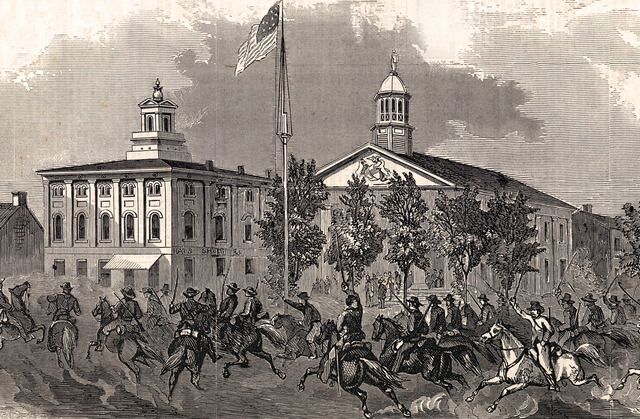

The news reached Philadelphia on a bright June morning in 1863; Gen. Robert E. Lee’s army had invaded Pennsylvania and was heading virtually unopposed to the state capitol. Suddenly, a Post correspondent wrote, the city was filled with a militant spirit.

“One could scarcely turn in any direction without meeting with a fife and drum. Recruiting officers were constantly marching up and down the streets. Large four-horse omnibuses, with bands of music and placards announcing various [assembly points], were driving about the city.

“The apathy, that for a time had seemed to taken possession of the community, was speedily dispelled. The possibility that the rebel horde might reach the Susquehanna, and even cross that stream and destroy our state capitol, was freely entertained yesterday; but there was also a firm resolve, ‘that many a banner should be torn, and many a knight to earth be borne’ before that disgraceful calamity should befall the state.”

In Harrisburg, Pennsylvania—100 miles closer to the approaching Confederate Army—the mood was quite different. There, residents had panicked after hearing that the rebel army had looted Chambersburg, Pennsylvania. Swarms of frantic passengers gathered at the railroad station, desperate to fit into any railway car they could find. The roads out of town were choked with wagons piled high with household effects, bearing families away from the enemy, and the inevitable battle.

The North’s confidence, which ran so high when the war began, was showing signs of collapse. There seemed to be little enthusiasm for fighting. The governor’s call for an emergency militia of 60,000 men was met with only 16,000 volunteers.

The Federal Army was also running low on its supply of soldiers. The eager recruits who had signed up at the war’s beginning were now approaching the end of their two-year enlistment. By the end of the month, more than 30,000 soldiers were due to leave the army. At the same time, enlistments of new recruits were falling behind goals. Men throughout the North were reluctant to sign up with an army that was so often defeated.

Faced with a drastic shortage, Congress passed the unpopular Enrollment Act, which set up the machinery for drafting 300,000 men. The Post editors disliked the idea of this conscription law, particularly its clause that allowed men to hire substitutes or buy exemptions.

Faces of the American Civil War

Photos courtesy The Library of Congress

A man who received a draft notice could hire another man to take his place in the fighting. If the substitute was found acceptable and duly sworn in, the draftee would be free of any obligation to serve, but only, the Post adds, for “the term for which he was drafted.” After the substitute had served the length of service, the original draftee would be again eligible for conscription.

If the draftee couldn’t find a substitute among poor citizens or struggling immigrants, he could simply buy a personal exemption for $300. (Congress set the amount at a level they felt would be affordable to working-class men. When you adjust that figure for 150 years of inflation, it comes close to $6,000 in 2013 money.)

Before the fighting had ended, the War Department had four separate draft calls, which drew the names of 776,000 American men. Few of these men ever saw military service. More than 20 percent never showed up. Another 60 percent were disqualified for physical or mental disability, or because they were the sole support of a motherless child, a widow, or an indigent parent.

Once sworn into service, recruits and draftees were rushed through basic training before being sent to the front. With only minimal instruction and poor leadership, a Post article claimed, it wasn’t surprising that Union troops had been repeatedly outfought by the Confederates. It quoted a Union army officer who had watched the unskilled Yankees at Chancellorsville:

“They have been taught to load and fire as rapidly as possible, three or four times a minute … they go into the business with all fury, every man vying with his neighbor as to the number of cartridges he can ram into his piece and spit out of it! The smoke arises in a minute or two so you can see nothing or where to aim. The trees in the vicinity suffer sorely, and the clouds a good deal. By-and-by, the guns get heated and won’t go off, and the cartridges begin to give out.

“Meanwhile, the enemy, lying quietly a hundred or two yards in front, crouching on the ground or behind trees … rise and advance upon us with one of their unearthly yells, as they see our fire slackens. Our boys, finding that the enemy has survived such an avalanche of fire we have as we have rolled upon them, conclude that he must be invincible, and, pretty much out of ammunition, retire.

The editors urged the army to abandon the practice of forcing men to load and fire in unison. “Accurate loading, and slow firing, at will, and only when the soldiers has an idea that his ball will tell, will do more execution than hasty loading, and rapid firing at something or nothing.”

It was well-intended advice, but would have been useless during the intense fighting at Gettysburg, where soldiers found themselves loading and firing “as rapidly as possible” simply to hold their ground.

By June 28, Lee learned the Union Army had pursued him across 120 miles in 10 days—a remarkable feat of marching at a time when 5 miles a day was a good speed for an army. He began gathering his forces for a massive blow against the Union army, which he hoped he could deliver at Gettysburg.

He couldn’t have known that a Union general, John F. Reynolds, was also hoping for a fight at Gettysburg because he’d already picked the best ground for his troops.